Introduction

The pelvic inlet also referred to as the superior pelvic aperture or upper pelvic narrow, is the anatomical limit between the true pelvis inferiorly and the false pelvis superiorly. There are morphologic, genetic, and hormonal differences related to reproduction that differentiate the male and female pelvis.

In obstetrics, the pelvic inlet is the entrance to the birth canal. The fetal cephalic extremity must position itself and adapt adequately to compare the smaller diameter with the largest diameter of the space delimited by the anatomical line of the maternal pelvic inlet.

The shape of the inlet depends on the general shape of the pelvis, according to the traditional classification of Caldwell and Moloy.[1] The dimensions of its anteroposterior, oblique, and transverse diameters vary according to the morphological type of the pelvis. The proportions of the shape of the internal pelvic spaces correspond to the proportion of the sacral area of Michaelis.

Radiological evidence shows that the subject's posture changes the intrapelvic space. The position taken by the subject influences the values of the transversal and anterior-posterior diameters. This evidence is instrumental in facilitating fetal entry into the true pelvis and favoring the dilating phase of labor.[2]

Evaluating the diameters of the endopelvic spaces and their adaptability (mobility) would be beneficial for diagnosing the "contracted pelvis" and avoiding the consequences on the health of the mother and the newborn that protracted labor and an operative birth can involve.

Structure and Function

Bony Anatomy

The pelvic inlet involves three of the four elements of the bony pelvis. The pelvic brim has contributions from the first sacral segment, the ilium, and the pubis, but not the ischium. The pelvic inlet is delineated by a bony crest that defines its limit (the pelvic brim). The pelvic brim includes the promontory of the sacrum and continues inferolaterally towards the ilium traversing the rounded edge that separates the sacral bases from the anterior face of the sacrum itself: the linea terminalis. The pelvic brim continues laterally, crossing the sacroiliac joint, passes along the iliopectineal line in its initial portion as the linea innominata or arcuate line of the ilium (also called the "innominate bone"), continues along the pectineal line of the pubis (crest) where it passes along the superior-posterior edge of the pubis and the pubic tubercle, and ends just lateral to the pubic symphysis.

Along the internal face of the ilium, the arcuate line ends behind the anterior angle that separates the superior and inferior portions of the auricular surface, which is articulated with the sacrum. Tracing an imaginary line that continues posteriorly, the pelvic brim continues towards the posterior superior iliac spine after passing through the inferior iliac tuberosity. In this way, by analogy, the pubic tubercle and the pubic symphysis are the anterior junction bridge of the two halves of the pelvic inlet, while the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and the space between the ilia (sacroiliac joints and anterior and posterior ligaments) are the extremes of the posterior bridge.

Visceral Structures

The sigma crosses the upper pelvic narrow with the root of the mesosigma (at the level of the left sacroiliac joint), the ureter, and the vas deferens. Sometimes even the cecum and the appendix descend into the pelvis from the right iliac fossa, near the right sacroiliac joint. The bladder dome tends to protrude beyond the upper strait when the bladder is full, along with the medial vesicoumbilical ligament (vestiges of the urachus) and the medial vesicoumbilical folds (vestiges of the umbilical arteries). The parietal peritoneum is the deepest parietal structure that crosses the upper pelvic narrow.

Embryology

The pelvic skeleton forms via mesenchymal condensation and endochondral ossification. The first ossification center develops in the ilium in the early-fetal period. Multiple sites ossify and continue to develop after birth until adolescence.

The fetal pelvis, including subpubic angle, width, and depth of the sciatic notch, varies with biological sex. However, the growth of the ischium and pubis and the ischiopubic indices do not change with age. Sex differences in pelvic morphology may be recognized in fetuses at nine weeks from fertilization (or 11 weeks from the last menstrual period) after the sex chromosomes were activated.[3]

The connections and articulations of the cartilage in the pelvis are essential for pelvic ring formation in a limited period: between 54 to 60 days after fertilization, at around eight weeks embryonic period, or ten weeks gestation. The normal period is necessary to initiate effective fetal movements that may induce mechanical forces and affect normal skeletal development. Fetal movement may also explain some variations in pelvic shape observed later. Observations done later during the fetal period have shown that the most frequent shape of the pelvic inlet is similar between sexes: android type in 56% of male fetuses and 54% of female fetuses. It seems to indicate the importance of environmental factors in defining pelvic shape.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The division of the iliac vessels from common iliac vessels to the external and internal iliac vessels occurs anterior to the sacroiliac joint. The internal iliac vessels descend into the true pelvis, while the external iliac vessels run along the medial belly of the psoas muscle and parallel to the pelvic brim. More inferiorly, the obturator vessels similarly traverse the edge of the pelvic brim.

The structure running most closely along the pelvic brim is the umbilical artery, located above the obstructive vascular-nervous bundle in contact with the osseous-ligamentous plane of the pelvic inlet. The middle sacral artery originates from the abdominal aorta in the angle formed by the emergence of the common iliac arteries, then passes over the sacral promontory to descend to the coccyx. The retropubic branch of the epigastric artery (a branch of the external iliac artery) bypasses the pelvic brim in its anterior hemicycle.

The same happens for the ovarian vessels (but not the testicular ones that enter the inguinal canal from the internal orifice) and the round ligament of the uterus with its vessels.

Nerves

The obturator nerve must cross the pelvic inlet and the fourth and fifth lumbar roots of the lumbosacral plexus. The lateral-vertebral chain of the orthosympathetic system passes anterior to the sacral bases.

The superior hypogastric plexus runs anterior to the abdominal aorta and sacral promontory to descend and mix its fibers with the inferior endopelvic hypogastric plexus. The union of the superior and inferior hypogastric plexuses provides innervation to gastrointestinal and genital organs in the pelvis.[4]

Muscles

Few myofascial structures insert on the bony edge of the pelvic inlet, yet it is bypassed by many vascular, nervous, and visceral structures. These structures may be impacted by compressive forces while the fetal head is about to engage inside the pelvis in the last week of gestation.

Muscle Structures

On the edge of the pelvis (the pelvic brim), the lower portion of the iliopsoas muscle is inserted posteriorly, straddling the sacroiliac joint before the muscle belly moves forward toward the pubis, sliding parallel to the pelvic brim with its medial border. It is covered by the band that below continues, after passing the arcuate line, on the upper insertion of the obturator internus muscle. The pectineus muscle originates anteriorly with respect to the pubopectineal crest of the pelvic inlet. The psoas minor muscle, inconstant, can insert directly on the pectineal line and its ligament.[5]

Ligaments and Bands

The anterior longitudinal ligament, which runs anteriorly along the entire length of the vertebral column, continues with the sacral periosteum at the level of the promontory. A small bundle of the anterior iliolumbar ligaments, which is part of the fibrous capsule of the sacroiliac joint, has a curvilinear inferior course that is inserted anteriorly on the arched line.[6] The inguinal ligament has its main anteroinferior insertion on the pubic tubercle. It continues with the lacunar ligament, forming a robust thickening as the iliopectineal ligament, which is found on the continuation of the innominate line of the ilium.

The inguinal ligament is the continuation of the abdominal transverse muscle fascia, which originates posteriorly from the lumbar region as a continuation of the thoracolumbar fascia. The iliolumbar ligaments thicken and continue with the thoracolumbar fascia on the anterior side of the lateral aspect of the spine.

Physiologic Variants

Morphology of the Pelvic Inlet

The general shape of the pelvis was defined in a historical publication of the 1930s by Caldwell and Moloy. The shape of the circumference of the pelvic narrow, the internal space of the pelvis, depends on the overall shape of the pelvis itself.

The shape of the female pelvis has been divided into four classes by Caldwell and Moloy, who report the following proportions on a population of 147 cases: gynoid, 41.4%; android, 32.5%; anthropoid, 23.5%, and platypelloid, 2.6%. Each has peculiar characteristics regarding the width of the sub-pubic angle, the height of the pelvis, the transverse diameters of the three pelvic planes (inlet, mid pelvis, outlet), and the shape of the circumference of the upper pelvic narrow [1].

The inlet of the gynoid pelvis appears to be ovoid, with a transverse diameter just greater than the anterior-posterior diameter. The android pelvis has a heart shape, with the greatest width of the transverse diameter moved towards the sacrum. The obstetric conjugate of the anthropoid pelvis is much greater than the transverse diameter. In the platypellic pelvis, the inlet is wide and very narrow. The shape depends on both genetic factors and environmental factors such as nutrition and lifestyle. Food deficits or infectious diseases lead to pelvic deformations, which fortunately are now part of the past. Severe forms of adolescent scoliosis can affect pelvic morphology, as well as congenital hip dislocation, and probably also fetal posture in utero (unpublished personal observations).

A 1996 Abitbol study correlates pelvic morphology to factors such as hormone tone, the age at which upright positional behavior and walking are achieved, and intense sports activity in adolescence.[7]

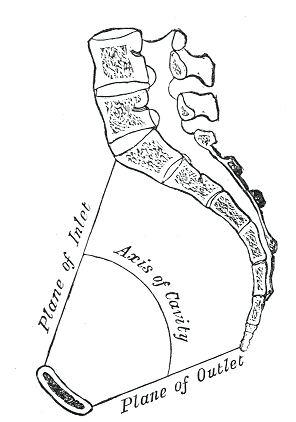

The Orientation of the Pelvic Inlet

The pelvic inlet has an inclination of about 55 to 60 degrees with respect to the anatomical horizontal plane. Major or minor angles mean pelvic retroversion, anteversion, and posterior or anterior pelvic tilt. The general inclination of the pelvis is maintained by the balance tension between different muscular and fascial anatomical components. The thoracolumbar fascia plays a fundamental role in the statics and dynamics of the pelvis and its relationship with the shoulder girdle, which is essential for maintaining posture, walking, and coordinated movements of the limbs. According to Cottingham (1988), the front tilt corresponds to a general orthosympathetic tone, while the posterior pelvic inclination corresponds to a relative parasympathetic tone.[8][9]

The muscles that maintain the inclination are mainly those of the abdominal "box:" the anterior and lateral abdominal muscles (which contribute with their bands to the formation of the inguinal ligament), the paravertebral muscles, the psoas major and the piriformis muscles; the thoracoabdominal diaphragm and the pelvic floor. In the hamstrings muscles group, the biceps femoris muscle is mentioned for its proximal insertion on the ischial tuberosity in continuity with the sacrotuberous ligament, which is one of the main thickenings of the sacral-lumbar-thoracic fascia complex.

Clinical Significance

Pelvic External Morphology and Pelvic Inlet

The traditional external pelvimetry of Baudelocque rose from the hypothesis that the external shapes and dimensions of the pelvis corresponded to the internal ones. Current literature confirms the correlation.[10]

One can trace and measure the oblique diameter, the transverse diameter, and the anterior-posterior or conjugated diameter for the pelvic inlet. The shape of the inlet is regulated by the relative proportions between the transverse diameter and the obstetric conjugate.[11]

The sacral diamond area would externally correspond to the pelvic inlet: the transversal and longitudinal diameters of the Michaelis sacral area will have a specific reciprocal relationship for each type of pelvis, matching the shape of the pelvic inlet. The transverse diameter of the sacral rhombus-shaped area of Michaelis is the distance between the two posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS).[12] The longitudinal diameter is described between the tip of the spinous process of the fifth lumbar vertebra at the top and the upper limit of the intergluteal groove, corresponding to the fourth-fifth sacral segment.

The two diameters of the sacral diamond area usually have the same dimensions. However, sometimes the longitudinal one is larger than the transverse (the opposite is uncommon), and they intersect at their middle point. Occasionally the transverse diameter, which intersects the longitudinal one at the level of the second sacral segment, will divide the latter into two unequal parts: the upper part of the longitudinal diameter is shorter than the lower portion.

The dynamics of the biomechanical movement will be different depending on the pelvic morphology for the same principle. The fascia anatomy of the sides of the sacral diamond area, which regulates its shape and movement, corresponds to the fascial thickenings that are part of the sacral complex of the thoracolumbar fascia, which surrounds the sacroiliac joints both posteriorly and, from the iliolumbar ligaments, anteriorly. The biomechanical properties of the bands would have repercussions from the inside to the outside and vice-versa.[6] The shape of the posterior muscular and adipose tissues seems to correspond with the general pelvic morphology. The classification is as follows: the gynecoid pelvis corresponds to a round buttocks shape, the platypelloid pelvis to a triangular shape, the anthropoid pelvis a square shape, and the android pelvis to a trapezoidal gluteal form.[13]

The diameters of the sacral area were utilized in detecting cephalo-pelvic disproportion followed by complicated labor and dystocia, resulting in a correlation between the transverse diameter and the complications during childbirth.[12][10][14][15]

Diameters of the Pelvic Inlet

The pelvic inlet is an irregular circumference; three diameters can be defined.

The anteroposterior (or "conjugate") diameter is the distance between the pubic symphysis and the sacral promontory. Three distances are:

- The anatomical conjugate or true: Measured between the sacral promontory and the upper edge of the pubic symphysis and measures an average of 11.0 cm

- The obstetric conjugate: Measured from the sacral promontory to the point bulging the most on the back of the symphysis pubis, located about 1 cm below its upper border. It measures 10.5 cm on average; it is the lesser anteroposterior diameter.

- The diagonal conjugate: Measured between the sacral promontory and the lower edge of the pubic symphysis, measuring an average of 12.5.

The anterior-posterior diameter can also be evaluated with external pelvimetry using the various types of pelvic tubes. According to the classical explanation of Baoudeloque, the external conjugate is measured from the upper edge of the pubic symphysis anteriorly to the first sacral segment posteriorly ("the depression one centimeter under the spinous process of the fifth lumbar vertebra"), its dimensions are about 20 cm.[10]

The oblique diameter is the largest of the three; it is the distance between the arched line near the sacroiliac joint posteriorly and the pubopectineal line anteriorly. This is the diameter on which the fetal head presents; it measures about 12 cm. The transverse diameter is the distance between the two innominate lines at their widest point, measuring approximately 13 cm. The entrance of the fetal head into the pelvic excavation normally takes place through a rotation from the oblique diameter to the transversal diameter. External pelvimetry can also evaluate the transverse diameter by measuring the distance between the two upper posterior iliac spines (PSIS). The average distance between the two PSIS is about 11 cm.[10]

Other Issues

Endopelvic Biomechanical Dynamics

An interesting longitudinal study of 2016 that appeared in PNAS shows that the pelvic form in both genders is not static but changes with age. The pelvic morphology seems to change every two decades due to re-modeling and general bone reshaping.[16] For women, the pelvic form, which has the largest internal diameters, is present between 20 and 40 years: the age of sexual maturity and pregnancy with lower risk.

Two radiological studies in MRI have explored the possibility of evaluating the endopelvic diameters of subjects positioned in different postures: in the supine position, on the "all-fours" (supporting herself on her hands and knees), and in kneeling squats. Significant changes have been highlighted in the change of position with a decrease in the diameters of the conjugate of about 3 mm, an increase in the anteroposterior diameters of the mid-plane, and the outlet of 4 and 5 mm, while the transversal diameters show an increase about 15 mm. The study was performed on two groups of women: pregnant and not pregnant. The results were the same. The pelvic inlet showed less difference than the outlet and the mid-pelvis: it could mean that in changing position, the inlet modifies its shape and inclination more on the horizontal plane than its transverse diameter.[2][17]

In the clinical obstetric and osteopathic fields, evaluating the quality of the posterior pelvic movement is proposed as a general indication of the possibility of vaginal delivery. The diameters of the sacral area are the transverse diameter that lies between the two posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) and the longitudinal diameter stretched between the spinous apophysis of the fifth lumbar vertebra and the beginning of the intergluteal groove (the "diamond test," taught for decades in the osteopathic practice). They should increase their amplitude when the pregnant subjects go from standing upright to squatting. Depending on possible amplitude restriction of the range of motion, a joint (sacroiliac, hip, or pubis) or fascial/ligamentous dysfunction could be hypothesized.

Pelvimetry and Obstetrics: Past and Present

The classical external pelvimetry, whose foremost representative was the French medical doctor Baudelocque in the 18th century, was abandoned with the advent of the technological era. It had been an attempt to explain the reasons for dystocia without offering any means to solve the problem.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the radiologic exam shed new light on static pelvimetric evaluation with the possibility of directly measuring the internal diameters; however, this method was also disappointing. MRI has made measurements easier and more precise due to reproducible scans. The ability to record images with motion has made it possible to see live childbirth and confirm that the change of position of the parturient modifies the internal pelvic diameters.[2] This information was intuitively known and used by midwives for several centuries.

The evidence illuminated by the radiological studies supports the research and definition of a clinical test of external pelvimetry. The present qualitative test in pelvimetry, currently suggested in obstetric and osteopathic settings, has some practical limitations like the lack of standardization, the difficulty for most pregnant women near term gestation to come down smoothly into a squatting position, and the lack of reference curves and cut-off values.