Continuing Education Activity

Pancreatic cancer refers to the carcinoma arising from the pancreatic duct cells, pancreatic ductal carcinoma. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. The 5-year survival rate in the United States ranges from 5% to 15%. The overall survival rate is only 6%. Surgical resection is the only current option for a cure, but only 20% of pancreatic cancer is surgically resectable at the time of diagnosis. This activity describes the pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Describe the risk factors for pancreatic cancer.

Review the presentation of a patient with pancreatic cancer.

Summarize the treatments for pancreatic cancer.

Explain the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer refers to the carcinoma arising from the pancreatic duct cells, pancreatic ductal carcinoma. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. The 5-year survival rate in the United States ranges from 5% to 15%. The overall survival rate is only 6%. Surgical resection is the only current option for a cure, but only 20% of pancreatic cancer is surgically resectable at the time of diagnosis.[1][2][3][4]

Close cooperation among various specialties, including surgeons, oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, and radiologists, is extremely important for the chance of survival in patients with resectable disease and borderline resectable disease.

Etiology

Pancreatic Cancer Risk Factors

- Smoking (20% of pancreatic cancers are caused by smoking)

- Age older than 55 years old

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Cirrhosis of the liver

- Helicobacter pylori infection

- Work exposure to chemicals in the dry cleaning and metalworking industry

- Males more than females

- African Americans more than whites

- Family history

Ten percent have a genetic cause such as genetic mutations or association with syndromes such as Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, VonHipaul Lindau syndrome, and MEN1 (multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1).

Possible risk factors include heavy alcohol consumption, coffee consumption, physical inactivity, high red meat consumption, and two or more soft drinks per day.

Epidemiology

Based on the GLOBOCAN 2012 estimates, pancreatic cancer kills more than 331,000 people per year and ranks as the seventh principal cause of cancer death in both genders. The estimated global 5-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer is about 5%.

Incidence rates for pancreatic cancer for both genders were highest in Northern America, Western Europe, Europe, and Australia/New Zealand. The lowest incidence rates are in Middle Africa and South-Central Asia.

There are some gender differences globally. In men, the greatest risk of developing pancreatic cancer is in Armenia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Japan, and Lithuania. The lowest risk for men is in Pakistan and Guinea. In women, the highest incidence rates are in Northern America, Western Europe, Northern Europe and Australia/New Zealand. The lowest rates for women are in Middle Africa and Polynesia.

The incidence rates for both genders increase with age; the highest is older than 70 years. Approximately 90% of all cases of pancreatic cancer are among people over 55 years of age.

Pathophysiology

Pancreatic cancer can be of adenocarcinoma origin, serous, seromucinous, or mucinous.

Histopathology

More than 90% of adenocarcinomas of the pancreas are duct cell adenocarcinomas, with other types being cystadenocarcinoma and acinar cell carcinoma. Two-thirds arise in the pancreatic head; one-third arise in the rest (body and tail of the pancreas). Several research articles have evaluated the genetic nature of various subtypes of pancreatic cancer, providing an overall genetic makeup of pancreatic cancer. These genetic patterns can later be used to create targeted therapy, potentially improving survival in pancreatic cancer patients.

Toxicokinetics

Tumor markers associated with pancreatic cancer include CEA and CA 19-9.

History and Physical

Patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas typically present with painless jaundice (50%), usually due to obstruction of the common bile duct from the pancreatic head tumor. Weight loss occurs in about 90% of patients. Abdominal pain occurs in about 75% of patients. Patients can have weakness, pruritus from bile salts in the skin, anorexia, palpable, non-tender, distended gallbladder, acholic stools, and dark urine. Sometimes, patients may present with recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) due to hypercoagulability that prompts clinicians to suspect cancer and a full workup of cancer. See Image. Pancreatic Cancer, Courvoisier Sign.

Patients can also present with recent-onset diabetes.

Lab findings will include elevation in liver function tests, direct and total bilirubin levels, elevated amylase and lipase, and elevated pancreatic tumor markers (CA 19-9 and CEA).

Evaluation

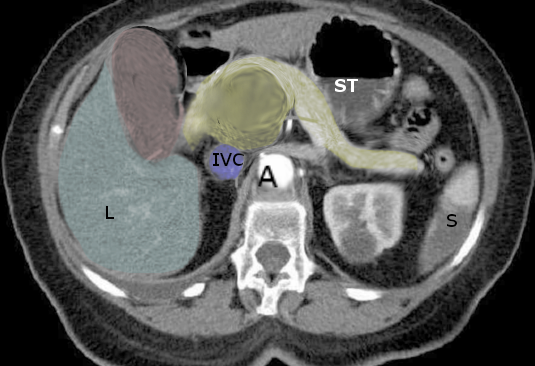

If adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is suspected, multidetector computed tomography, MDCT, is the best imaging modality to diagnose and evaluate the extent of disease, including perivascular extension and distant metastasis. MDCT is 77% accurate in predicting resectability and 93% accurate in predicting unresectability.

Multidetector CT protocol for pancreatic imaging utilizes a multiphase imaging technique, including a late arterial phase and a portal venous phase after administration of intravenous contrast material. The late arterial or pancreatic phase is acquired at 35 to 50 seconds after the injection and allows optimum evaluation of the pancreatic parenchyma. The portal venous phase is acquired at 60 to 90 seconds after the injection of intravenous (IV) contrast, allows for optimum assessment of the venous anatomy, and is best for the detection of hepatic and distant metastatic disease. Water can be used as oral contrast. Barium-based oral contrast is generally not used, as it will interfere with the evaluation of vascular anatomy and encasement. Multiplanar reformatted images in the coronal and sagittal plane, maximum intensity projection images, and volume-rendered images are helpful in delineating vascular encasement and narrowing better.

PET CT scan can be useful in detecting distant metastatic disease.

Abdominal MRI /MRCP with IV contrast is as good in the preoperative evaluation of pancreatic cancer and the assessment of vascular invasion. MRI is more sensitive to detect metastatic hepatic disease, with a sensitivity approaching 100% compared with 80% for CT. MRI also employs a standard multiphase post-contrast imaging protocol. There is a small subset of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which will provide the same attenuation on CT scans so that it will be more conspicuous on MRI. If pancreatic cancer is highly suspected and the CT scan is negative, that would be an indication to order further imaging with MRI of the abdomen with IV contrast. The downside to MRI is that if the patient cannot follow breathing instructions or has difficulty holding their breath, the images will be of poor quality. CT images are much faster to obtain and do not require significant breath-hold ability.

Ultrasound is of limited value in pancreatic imaging. Often, the pancreas will be poorly visualized sonographically secondary to bowel gas. Ultrasound can detect the secondary biliary ductal dilatation associated with pancreatic head cancer, but it is not helpful in visualizing the pancreatic mass itself.

ERCP with endoscopic ultrasound can be performed, and fine-needle aspiration biopsies can be done of suspicious lesions for the pathologic specimen. However, with a mass in the pancreas, biopsy confirmation is not necessary, and one can proceed directly to excision, given that a full workup has been performed.

Endoscopic ultrasound, a test performed by gastroenterologists, can delineate the pancreatic mass and can be used to biopsy the mass under ultrasound guidance.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a test in which an endoscope injects a contrast dye into the biliary duct and pancreatic duct. The level of biliary or pancreatic obstruction can be delineated. In some cases, the placement of a biliary stent can help relieve symptoms of jaundice.

Two important definitions in the evaluation steps of pancreatic cancer are borderline and unresectable tumors. Generally, pancreatic cancers are categorized as resectable or non-resectable tumors according to the vascular involvements and evidence of distant metastasis. Metastatic disease in the liver, peritoneum, omentum, and extra-regional lymph nodes are considered unresectable. The presence of vascular involvement (greater than 180 degrees of the superior mesenteric artery and celiac artery) also categorizes the patients in the unresectable group. However, in the case of superior-mesenteric vein involvement, the potential options for reconstruction should be evaluated carefully. Collectively, according to the published consensus by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the following characteristics in the pancreatic head and uncinate process are indicators of unresectability: 1. greater than 180 degrees involvement of the SMA and/or celiac axis, 2. presence of solid tumor contact with the first jejunal SMA branch, 3. SMV or portal vein involvement that is not amenable for reconstruction, and 4. evidence of contact with the most proximal draining jejunal branch into the SMV. The presence of the following features would categorize the pancreatic body and tail lesions: 1. greater than 180 degrees involvement of SMA and or celiac axis, 2. aortic involvement, 3. SMV or portal vein involvement that is not amenable for reconstruction. Borderline pancreatic tumors include tumors with short-segment occlusion of the SMV or SMV-portal vein confluence or hepatic artery. [5]

Treatment / Management

If the pancreatic adenocarcinoma is considered locally advanced, then by definition, it is unresectable. Neoadjuvant treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiation is typically preferred in this situation. Treatment with chemotherapy takes approximately.

If the adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is located in the head of the pancreas, then the Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) is the procedure of choice. If the tumor is in the body or tail of the pancreas, the distal resection is needed. Postoperatively, patients may receive chemotherapy with 5-FU, gemcitabine, and radiotherapy. If the hepatic artery is involved in the tumor, then the tumor is considered to be unresectable. However, if the superior mesenteric vein is involved in the tumor, then resection and vascular reconstruction. The same is true for portal vein involvement. It can be resected and reconstructed with a graft.[6][7][8][9][10]

If the adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is located in the body or tail of the pancreas, then the surgical procedure of choice is distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy. If there is extensive involvement of the celiac artery and splenic artery, a modified Appleby procedure can be performed if it meets the criteria.[11]

Minimally invasive approaches to Whipple and distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy have been investigated with similar outcomes in survival, morbidity, and mortality [12].

Differential Diagnosis

Typically, at the time of diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, 52% have distant metastasis, and 23% have local spread.

Differential diagnosis before imaging and biopsy includes the following: acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, cholangitis, cholecystitis, choledochal cyst, peptic ulcer disease, cholangiocarcinoma, and gastric cancer.

Surgical Oncology

The neoadjuvant first approach in resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma is implemented more and more frequently at high-volume centers nationwide and internationally. The rationale behind the neoadjuvant first approach is that the patient is in the best shape to receive chemotherapy and at the best odds of completing chemotherapy for 4 to 6 months. In addition, tissue is thought to be well-oxygenated, having not undergone a large procedure such as the Whipple. Many patients do not complete or even start adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection, thereby decreasing their survival. [13]

SWOG 1501 Trial recently evaluated neoadjuvant treatment first approach in resectable pancreatic cancer with disappointing results. Only approximately 73% went on to have a resection. Survival rates were comparable to those of adjuvant trials [14].

Radiation Oncology

There is a role for radiation therapy in combination with chemotherapy to treat locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Radiation therapy was originally used to alleviate pain, but its use is currently becoming more widespread to shrink tumors and increase survival.

Medical Oncology

Most patients who are deemed possibly resectable for pancreatic cancer should receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The two main regimens used are FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine plus protein-bound paclitaxel [15]. Many patients who are younger, fit, and have minimal comorbidities are offered FOLFIRINOX (a combination of 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan). This regimen is extremely toxic, and only fit young patients can withstand it. Patients who are older and/or not as healthy might be offered gemcitabine and protein-bound paclitaxel. Protein-bound paclitaxel is a taxane that is an albumin conjugate and has a lower risk profile than FOLFIRINOX. Of note, these two regimens were initially used for postoperative use. Now, however, these regiments are considered before and after surgery. The typical duration of each regimen is 4 to 6 months [16].

Pain management is extremely important. Pancreatic cancer is one of the most painful malignancies. Opioids, antiepileptics, and corticosteroids all are effective for pain relief.

Staging

Stage I: Tumor is located in the pancreas and does not extend elsewhere

Stage II: Tumor infiltrates bile duct and other near structures however, lymph nodes are negative

Stage III: Any positive lymph nodes

Stage IVA: Metastases into nearby organs such as stomach, liver, diaphragm, adrenals

Stage IVB: Tumor infiltrates distant organs

Inoperability is signified on imaging by superior mesenteric artery encasement, liver metastases, peritoneal implants, distal lymph node metastases, and distant metastases.

Prognosis

The prognosis for pancreatic adenocarcinoma remains poor despite advances in cancer therapy. The 5-year survival rate is approximately 20%. Prognosis after 1 year of diagnosis is dismal, with 90% of patients dying at 1 year despite surgery. However, palliative surgery can be of benefit.

Complications

Postoperative complications of pancreatic surgery include pancreatic fistulas, delayed gastric emptying, anastomotic leaks, bleeding, and infection.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

For patients with metastatic stage IV pancreatic cancer, discussions with the patient regarding treatment are essential. One can receive chemotherapy. However, the life prolongation will be, at best, months, yet it affects the toxicity and effects of the chemotherapy. It is important to keep nutrition at the forefront of the patient's care, as nutrition can affect wound healing.

Consultations

Palliative and/or supportive care, hospice, dietary, nutrition, physical therapy, occupational therapy

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is important to discuss with the patient all the treatment options before discussing surgery.

Pearls and Other Issues

Delayed gastric emptying is a common complication of the Whipple procedure. Similarly, anastomotic leaks pose significant morbidity to the patient.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of pancreatic cancer is with an interprofessional team that consists of an oncologist, general surgeon, radiologist, pain specialist, gastroenterologist, palliative care nurse, and an internist. By far, the majority of cases of pancreatic cancer are advanced at the time of presentation, and these patients have a very short life expectancy. Palliative care and a pain specialist should be involved in the care of these patients. Coordination of education of the family by the palliative nurse or provider is key because survival is severely reduced in most patients. The surgery for pancreatic cancer is complex and technically demanding. Even those who undergo successful resection may develop serious life-threatening complications which may alter the quality of life. [17] [Level 5]