Continuing Education Activity

Glycogen storage disease type I (GSD I), also known as Von Gierke disease, is an inherited disorder caused by deficiencies of specific enzymes in the glycogen metabolism pathway. It was first described by Von Gierke in 1929 who reported excessive hepatic and renal glycogen in the autopsy reports of 2 children. It comprises 2 major subtypes, GSD Ia and GSD Ib. In GSD Ia, there is a deficiency of enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) which cleaves glycogen to glucose thus leading to hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of glycogen storage disorders.

- Describe the presentation of a patient with glycogen storage disorder.

- Summarize the treatment of glycogen storage disorder.

- Explain modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by glycogen storage disorder.

Introduction

Glycogen storage disease type I (GSD I), also known as Von Gierke disease, is an inherited disorder caused by deficiencies of specific enzymes in the glycogen metabolism pathway. It was first described by Von Gierke in 1929 who reported excessive hepatic and renal glycogen in the autopsy reports of 2 children. It comprises 2 major subtypes, GSD Ia and GSD Ib.[1] In GSD Ia, there is a deficiency of enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase) which cleaves glycogen to glucose thus leading to hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis.[2] Patients with GSD 1b have normal G6Pase enzyme activity but have a deficiency of the transporter enzyme, glucose-6-phosphate translocase (G6PT).[1] Patients present with manifestations of hypoglycemia and metabolic acidosis typically around 3 to 4 months of age. In patients suspected of having the disease, genetic testing is the investigation of choice to confirm the diagnosis. Dietary treatment prevents hypoglycemia and improves the life expectancy of patients. However, to prevent long-term complications such as hepatic adenomas and renal failure, animal models of GSD I are being developed to study the disease more closely and develop new treatment strategies such as gene therapy.[3]

Etiology

GSD Ia results from mutations in the G6PC gene on chromosome 17q21 that encodes for the G6Pase-a catalytic subunit. GSD Ib results from mutations in the SLC37A4 gene on chromosome 11q23.3.[1]

Epidemiology

The incidence of GSD I in the overall population is 1/100,000 with GSD Ia and Ib prevalent in 80% and 20% respectively. The Ashkenazi Jewish population has a 5-times greater prevalence compared to rest of the population.[1]

Pathophysiology

The enzyme G6Pase is primarily expressed in the liver, kidney, and intestine. It has its active site on the luminal side of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Glucose-6-phosphate translocase is responsible for translocating Glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) from the cytoplasm into the ER lumen. The complex of G6Pase and G6PT catalyzes the final step of both glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis for glucose production. Deficiency of either causes an accumulation of glycogen and fat in the liver, kidney, and intestinal mucosa.[1][3]

Histopathology

The availability of gene sequencing makes liver biopsy unnecessary. However, a biopsy may be ordered by the gastroenterologist in view of hepatomegaly. Histological evaluation of the liver shows hepatocytes filled with glycogen that is periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase sensitive.[4]

History and Physical

Some patients with GSD I may present with hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis in the neonatal period. However, they are more likely to present at 3 to 6 months of age with hepatomegaly and/or signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, including seizures. Symptoms of hypoglycemia appear with increased intervals between feeds. Sometimes the infant may remain asymptomatic and would present with an enlarged liver and protruding abdomen. Those left untreated would develop an appearance similar to that seen in Cushing’s syndrome such as short stature, round face, and full cheeks. They have a failure to thrive along with delayed motor development. Cerebral damage resulting from recurrent hypoglycemic episodes may lead to abnormal cognitive development. In addition, patients with GSD Ib present with recurrent bacterial infections due to neutropenia.[1][2]

Evaluation

Initial laboratory findings in patients with GSD I will show hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, hyperuricemia, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertriglyceridemia. Besides these, patients with GSD Ib will have neutropenia ranging from mild to complete agranulocytosis.

In a patient suspected with GSD I, glucagon stimulation test should be avoided. It increases the risk of acute acidosis and decompensation by causing a significant increase in blood lactate with little or no increase in blood glucose concentration.

Instead of the invasive liver biopsy, noninvasive molecular genetic testing that includes full gene sequencing of G6PC (GSD Ia) and SLC37A4 (GSD Ib) genes is preferred for confirming the diagnosis. Sequence analysis has a detection rate of up to 100% but may miss certain mutations of both G6PC and SLC37A4 genes. For such cases techniques such as quantitative PCR, long-range PCR, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, targeted array, or comparative genomic hybridization analysis is employed.

The first choice to confirm the clinical suspicion of GSD I is a mutation analysis. After excluding patients with neutropenia, complete G6PC sequencing is performed. During the availability of liver biopsy tissue, G6Pase enzyme activity is analyzed to confirm the diagnosis.[1]

Treatment / Management

The main targets for the management of GSD I are the prevention of acute metabolic derangement, prevention of acute and long-term complications, attainment of normal psychological development, and good quality of life. Diet and lifestyle changes are made to prevent the primary concern of the disease, hypoglycemia. Monitoring of blood glucose along with the laboratory parameters should continue as with increasing growth, the child’s nutritional needs change. Fasting should be avoided, and frequent small feeds rich in complex carbohydrates along with fiber is recommended. Carbohydrates should make up for 60% to 70% calories.[1] Fructose and galactose are not metabolized to glucose-6-phosphate due to the deficiency of the enzyme. Therefore, a diet low in fructose and sucrose is recommended with limiting the intake of galactose and lactose to one serving per day.[5]

Initially, infants are fed soy-based, sugar-free formula on demand every 2 to 3 hours. With the increase in the infant’s sleep duration (longer than than 3 to 4 hours), it is important to avoid hypoglycemia during the overnight fast. Awakening the infant every 3 to 4 hours to monitor blood glucose and giving feeds is difficult. Therefore, it is important for the parents to be trained in inserting a nasogastric (NG) tube or a G-tube should be placed surgically. This allows the parents to administer feeds especially when the child is sick or refuses to eat.

In patients with GSD I, cornstarch has been used for the treatment of hypoglycemia as its slow digestion provides a steady release of glucose. This maintains the glucose levels for longer periods of time. In young children, 1.6 gm of cornstarch per kg body weight every 3 to 4 hours is recommended. While older children, adolescents, and adults, are given 1.7 to 2.5 gm of cornstarch per kilogram body weight.

All patients with GSD I should wear a medical alert bracelet. Along with blood glucose monitoring, a lactate meter can be a good tool to alert the parents especially in times of emergency. Hypoglycemia should be treated immediately with a fast-acting glucose source such as cornstarch or commercially prepared glucose polymers or over-the-counter diabetic glucose tablets.

Patients with GSD Ib have an increased risk of infections at the surgical site for G-tube due to neutropenia. Therefore granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is administered before placing a G-tube. The patients that receive G-CSF need a complete blood count (CBC) evaluation monthly along with the measurement of their spleen.

To avoid pump failures and occluded or disconnected tubing, bed-wetting devices that detects formula spilling onto the bed, infusion pump alarms, safety adapters, connectors, and tape for tubing is recommended as safety precautions. Limiting foods rich in lactose and sucrose such as fruits, juice, and dairy puts a child at risk for nutritional deficiency. The child should be carefully assessed, and diet should be supplemented with adequate micronutrients.

Oral citrate or bicarbonate is used to treat patients with persistent lactic acidosis. These agents alkalinize the urine and reduce the risk of urolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. Allopurinol reduces uric acid levels preventing recurrent attacks of gout. However, during an acute attack, Colchicine is preferred.[1]

Hyperlipidemia has only shown a partial response to medical intervention with statins, niacin, fibrates, and fish oil along with dietary interventions such as consuming medium-chain triglyceride milk. Its resolution has been reported with liver transplantation.[6][7]

Starting from infancy, systemic blood pressure measurement should be checked on every office visit while serum creatinine is evaluated every 3 to 6 months to monitor renal function. Patients with persistent microalbuminuria should be treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor to prevent worsening of renal function. [8] An echocardiography is recommended every 3 years beginning after the first decade of life or earlier in the presence of symptoms to screen for pulmonary hypertension.

Patients with GSD I have hepatomegaly universally due to fat and glycogen deposition in the liver. The common liver lesions seen in patients with GSD Ia include focal fatty infiltration, focal fatty sparing, focal nodular hyperplasia, peliosis hepatis, hepatocellular adenoma (HCA), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Therefore, a liver function test should be repeated every 6 to 12 months. Liver transplantation is an option for patients with multifocal growing lesions that do not respond to primary treatment.[1]

As per guidelines for the management of GSD I published by the collaborative European study[8], the following biomedical targets are recommended:

- Preprandial blood glucose greater than 3.5 to 4.0 mmol/L (63 to 72 mg/dL)

- Urine lactate/creatinine ratio less than 0.06 mmol/mmol

- Serum uric acid concentration in high normal range for age

- Venous blood base excess greater than - 5 mmol/L and venous blood bicarbonate greater than 20 mmol/L (20 meq/L)

- Serum triglyceride concentration less than 6 mmol/L (531 mg/dL)

- Normal fecal alpha-1 anti-trypsin concentration for GSD Ib

- Body mass index (BMI) between 0.0 and +2.0 standard deviations

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to differentiate GSD I from other diseases that present with hepatomegaly and or hypoglycemia. [1]

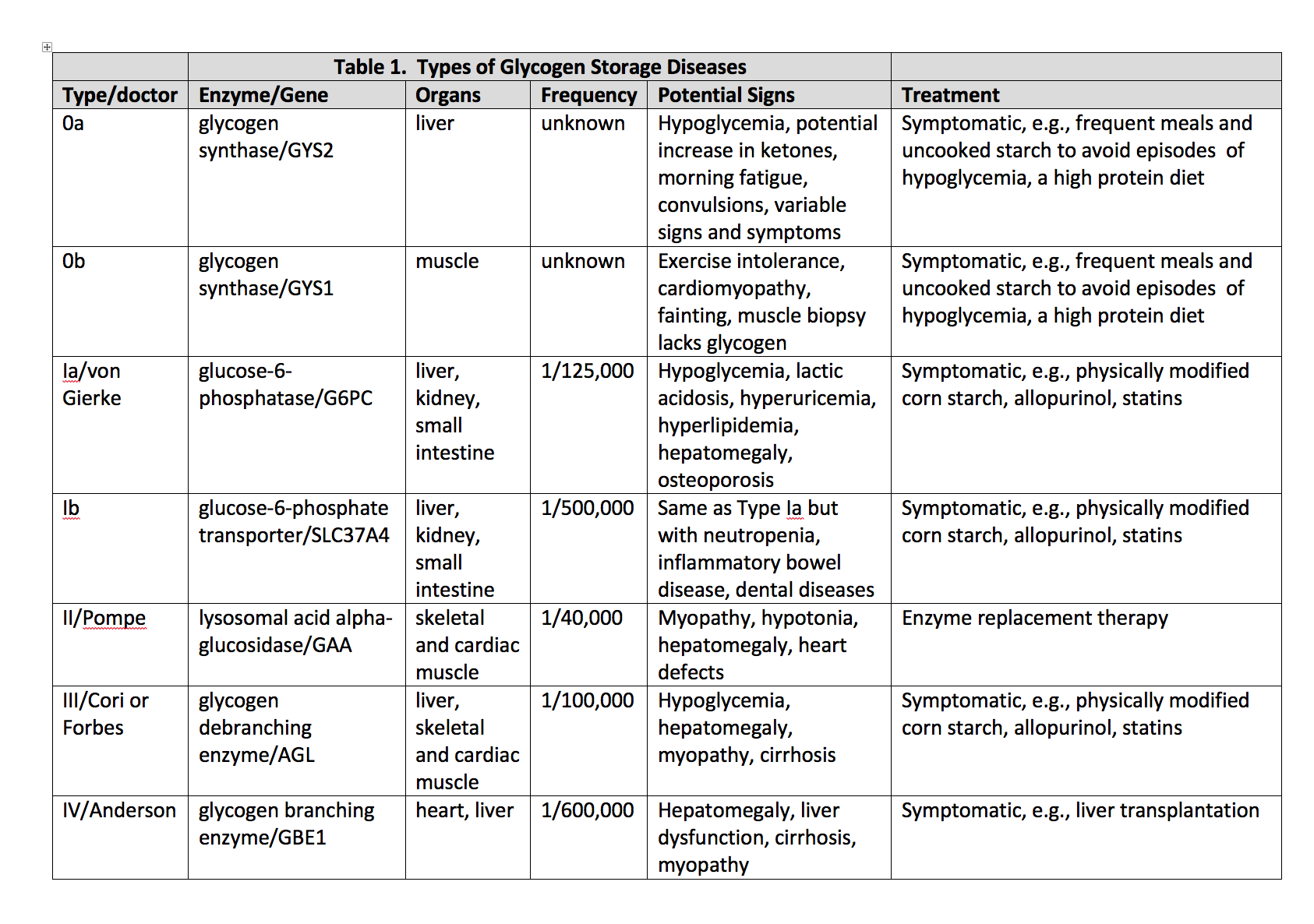

- GSD 0 (glycogen synthase deficiency)

- GSD III (glycogen debranching enzyme deficiency)

- GSD IV (branching enzyme deficiency)

- GSD VI (hepatic phosphorylase deficiency)

- GSD IX (hepatic form of phosphorylase kinase deficiency)

- GSD XI (Fanconi-Bickel syndrome due to glucose transporter protein 2 deficiency)

Disorders of Gluconeogenesis (Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase deficiency)

Primary liver disease (Hepatitis)

Niemann-Pick B disease

Gaucher disease

Hereditary fructose intolerance

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Dietary therapy is the first line treatment for patients with GSD I. However, to prevent long-term complications of the disease such as hepatocellular adenoma (HCA), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), renal failure among others, gene therapy in animal models of GSD is showing potential for the future trial in humans.[3]

Medical Oncology

The most likely etiology for HCC is the transformation of adenomas to carcinoma. In such patients, the diagnosis of HCC is challenging due to the abundance of adenomas making biopsy difficult along with normal levels of biomarkers like a-fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen.[9] Therefore, to detect hepatic adenomas early, ultrasound of the liver is recommended every 12 to 24 months until the age of 16 years which is then followed by CT or MRI every 6 to 12 months. If a hepatic adenoma is detected, liver ultrasound or MRI examinations is repeated every 3 to 6 months. Due to an increased risk of developing HCA, female patients with GSD I should avoid combined oral contraception.

Complications

Patients with GSD I may develop bleeding disorders from impaired platelet function. There is also an increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures from vitamin D deficiency. Therefore, routine monitoring of vitamin D levels along with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans is recommended to monitor the bone density and the need for vitamin D supplementation.

Renal failure may occur due to proximal renal tubular or renal glomerular dysfunction. Erythropoietin (EPO) production is decreased with worsening of renal function especially when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) drops below 50 ml/min/1.73 m. Thus patients then develop anemia of chronic kidney disease that may be further exacerbated by iron deficiency, chronic metabolic acidosis or bleeding diathesis. Anemic patients are treated with EPO therapy after screening them for iron deficiency and replenishing their iron stores. Patients with uncontrolled blood lactate, serum lipids, and uric acid levels are also at an increased risk for nephropathy that may need renal transplantation. Therefore, an annual ultrasound examination of the kidneys is recommended after the first decade of life.

Severe hyperlipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia (greater than 1000 mg/dL) increase the risk of xanthoma formation, acute pancreatitis, and early atherosclerosis.

Other complications include menorrhagia and polycystic ovaries in females, and gout from hyperuricemia.

Additionally, patients with GSD Ib have an increased risk of Crohn’s disease-like enterocolitis and hypothyroidism.[1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Genetic counseling for parents as each sibling of an affected patient has a 25% chance of being affected and a 50% chance of being an asymptomatic carrier.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Dietary therapy maintains the patient's blood glucose levels and reduces the early symptoms. However, to avoid long-term complications such as HCA, HCC, and renal failure, gene therapies in GSD I mice models showed promise. In early 2018, the FDA approved the first gene therapy clinical trial at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and UConn Health.