Introduction

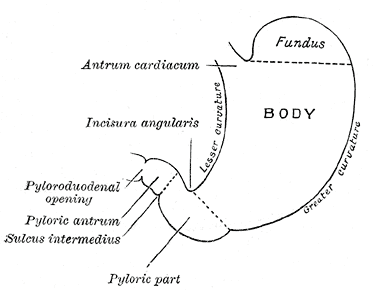

The stomach is an important organ and the most dilated portion of the digestive system. The esophagus precedes it, and the small intestine follows. It is a large, muscular, and hollow organ allowing for a capacity to hold food. It is comprised of 4 main regions, the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. The cardia is connected to the esophagus and is where the food first enters the stomach. The fundus follows the cardia and is a bulbous, dome-shaped, superior portion of the stomach. Followed by the fundus is the body or the main, largest portion of the stomach. Following the body is the pylorus, which conically funnels food into the duodenum, or upper portion of the small intestine. The stomach is located in the human body left of the midline and centrally in the upper area of the abdomen. After mastication or chewing, the next stage of digestion begins in the stomach.[1][2][3][4] See Image. Outline of the Stomach Showing its Anatomical Landmarks.

Structure and Function

The primary functions of the stomach include the temporary storage of food and the partial chemical and mechanical digestion of food. The upper portions of the stomach (cardia, body, and fundus) relax as food enters to allow for the stomach to hold increasing quantities of food. The lower portion of the stomach contracts in a rhythmic fashion (mechanical digestion) to aid with the breaking down of food and mixes it with stomach juices (chemical digestion) which also serve to break food down and prepare the mixture, termed chyme at this point of digestion, for further digestion. With intervals of about 20 seconds, mixing waves are produced, which increases with intensity as they reach the lower portion of the stomach. With each wave, the pyloric sphincter allows small quantities of sufficiently liquefied/ broken down chyme into the small intestine as can be handled and regulated by the duodenum. Stomach juices are liquids naturally secreted by the fundus portion of the stomach for the chemical purposes of digestion and include hydrochloric acid (HCl) and the enzyme pepsin. In addition to HCl, the stomach also produces intrinsic factor in its parietal cells. The intrinsic factor produced at this stage of digestion allows for the absorption of vitamin B12 (cobalamin) later on in the small intestine. The production of the intrinsic factor is critical as vitamin B12 plays an important role in the production of red blood cells and neurological functions. The stomach is capable of processing food and distributing it to the duodenum on average within 2 to 4 hours. However, this rate is heavily dependent on the type of food being consumed as carbohydrates are broken down in the stomach relatively fast, as are proteins, as opposed to fats such as triglycerides which take longer to be processed by the stomach. While the primary function of the stomach is not to absorb nutrients, it is capable of absorbing some substances. Some of these materials include water in the setting of dehydration, certain medications including aspirin, amino acids, ethanol, caffeine, and some water-soluble vitamins. Additionally, the acidic environment of the stomach may be lethal to many types of bacteria and other microorganisms that enter the body by way of ingestion, potentially protecting the body from infection and disease.[5][6][7][8]

Embryology

During the fourth week of development, the stomach begins to form as the most dilated portion of the foregut. During development, the stomach descends from the level of the C2 vertebrae to the level of the T11 vertebrae by week twelve consequent of rapid esophageal elongation. By the fifth week of growth, one side of the stomach (dorsal wall) grows faster than the other side of the stomach (ventral wall), resulting in the stomach being bulged more greatly on one side, giving it its characteristic shape. During week 7 of growth, the stomach rotates 90 degrees clockwise about the longitudinal axis and then clockwise about the anteroposterior axis during the eighth week, pulling the pyloric region upward, to its final position.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The stomach is an organ which requires a rich supply of blood as it is an area which is highly mobile and distensible, is composed of 5 different cell types functioning at high metabolic rates, and has multiple muscle layers to facilitate the stomach waves of brisk peristalsis for the second phase of digestion. The celiac trunk, branching directly anteriorly from the aorta provides the main arterial blood supply. The trunk supplies the common hepatic artery (CHA), splenic artery, and the left gastric artery (LGA). The less curved side of the stomach is proximally supplied by a descending branch of the LGA, with its ascending branch supplying portions of the esophagus. The CHA which runs superior to the pancreas and the right branches off to the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) and continues with the branch that proceeds from the CHA being the proper hepatic artery. The right gastric artery (RGA) then branches from the proper hepatic artery. The RGA then runs from right to left across the lesser curved portion of the stomach and continues to branch into smaller vessels through the body of the stomach to join the network of smaller arteries supplying the stomach as branched off from the LGA. The posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery (PSPDA) branches off of the GDA which then branches into the anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery (ASPDA) and the right gastro-omental (gastroepiploic) artery (RGEA). The RGEA then traverses and supplies from right to left the greater curvature of the stomach. The left gastroepiploic (gastroomental) artery (LGEA) branches from the splenic artery and also supplies the greater curvature body portion of the stomach, except beginning on the left side and moving and branch in the rightward direction. Three to 5 additional smaller arteries also branch from the splenic artery to supply the stomach. The left gastric (coronary) vein and the right gastric and right gastro-omental veins all achieve drainage into different segments of the portal vein. The short gastric veins (also termed the vasa brevia) and the left gastro-omental vein achieve drainage via the splenic vein.

The lymphatic drainage of the stomach can be understood as 4 levels. Level 1 includes the perigastric lymph nodes and follows a path of drainage of the right pericardiac, left pericardiac, along with the less curved body portion, along with the greater curved body portion, supra-pyloric, and infra-pyloric. Level 2 is comprised of drainage along the LGA, along the CHA), along with the celiac axis, at the splenic hilum, and along the splenic artery. Level 3 is characterized by drainage in the hepatoduodenal ligament, posterior to the duodenum and pancreas head, and at the source of the small bowel mesentery. Finally, the fourth level is characterized by mesocolic and paraaortic drainage.

Nerves

The autonomic nervous system provides the stomach with the innervation via parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves. The vagus nerve supplies parasympathetic innervation via the right posterior and left vagal trunks. Because of the rotation of the stomach during development, the left vagus nerve is anterior, while the right vagus nerve is posterior. The right vagus nerve branches to the criminal nerve of Grassi for innervation of the cardia and fundus. The trunks also follow the lesser curvature region of the stomach to form the posterior and anterior gastric nerves of Latarjet innervating the body, antrum, and pylorus. Sympathetically, nerves are supplied, including some fibers transmitting pain, to the celiac plexus from spinal cord segments T6 through T9.

Muscles

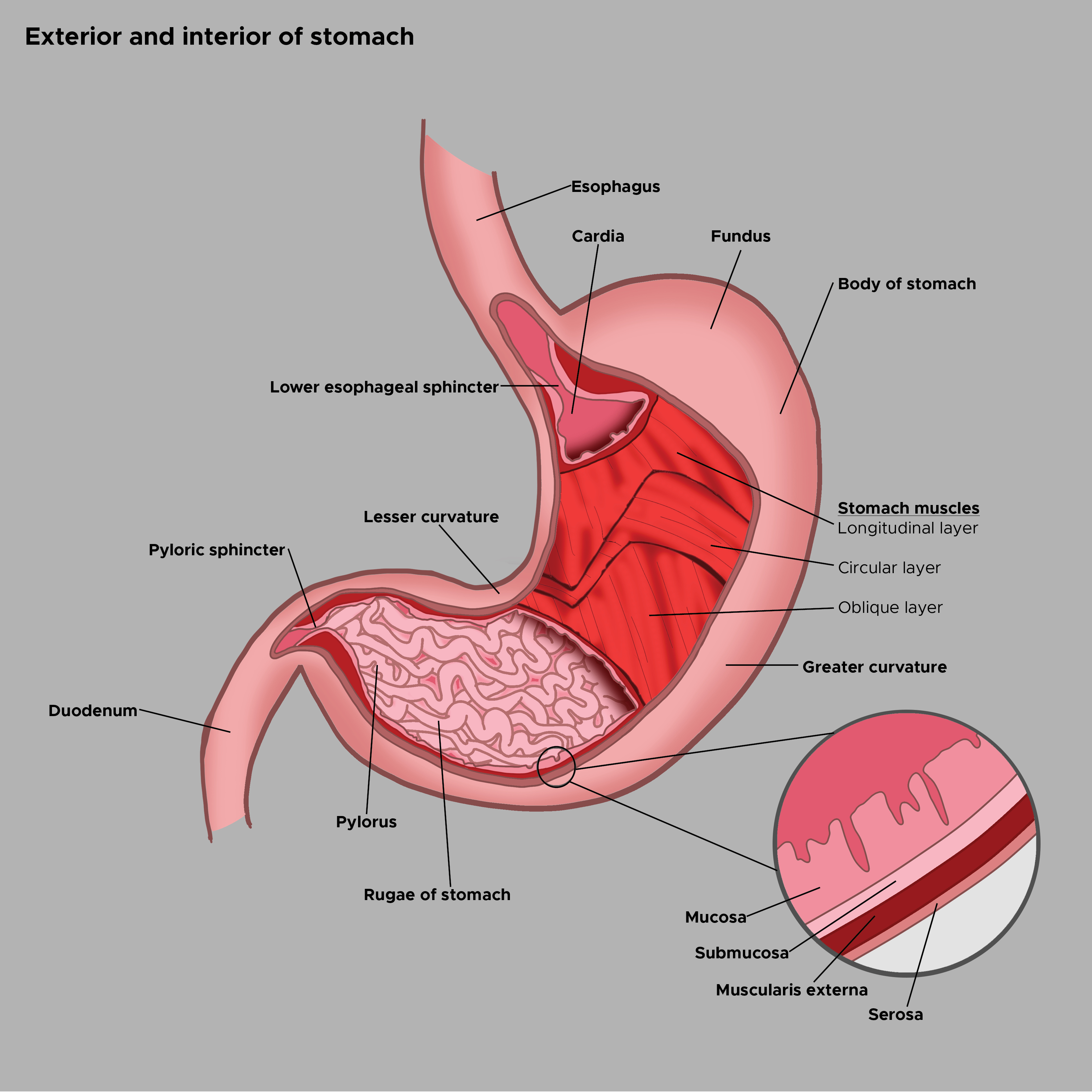

The stomach is heavily comprised of muscle tissue, arranged in 3 layers, running longitudinally, obliquely, and circularly as part of the stomach wall. Before the muscular structure of the stomach can be understood, it is first important to understand the different layers of the stomach wall. Four main layers constitute the stomach wall, including the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and the serosa. The innermost layer, the mucosa, is covered by epithelial tissue and is mainly comprised of gastric glands that secrete gastric juices. Particularly, the fundus region releases gastric juices while the cardia region secretes protective mucus which coats the inner mucosal wall of the stomach via mucus (Foveolar) cells thereby protecting the stomach muscles from being digested by the gastric juices produced by the chief cells (pepsin) and parietal cells (HCL). The submucosa is comprised of dense connective tissue and contains blood and lymphatic vessels along with nerves. Together, the submucosa supports the mucosal layer and has many folds analogous to that of an accordion called rugae which allows for distension of these layers when food enters the stomach. The muscularis externa is the next layer and is comprised of the three sub-layers mentioned above. The inner oblique layer is unique to the stomach and is primarily responsible for the churning, mechanical digestion of food. The middle circular layer is concentric with the stomach’s longitudinal axis and thickens in the region of the pylorus to form the pyloric sphincter responsible for regulating the output from the stomach into the duodenum. The next layer is the outer longitudinal layer, but between this layer and the middle circular layer, is Auerbach's (myenteric) plexus, which is a region of innervation for the two adjacent muscular layers. The outer longitudinal layer facilitates the movement of food in the direction of the pylorus via muscular shortening. The final layer, the serosa, is made up of multiple layers of connective tissue which also connect continuously with the peritoneum. See Image. Exterior and Interior of the Stomach.

Physiologic Variants

Stomachs do not have many natural physiological variations. Variations that are most common are related to the exact position, size, and shape which can be heavily related to diet. For example, rugae may remain distended if overeating occurs continuously with an individual. However, there does exist a variety of congenital abnormalities of the esophagus including the following:

- Gastric outlet obstruction

- Organ duplication

- Organ transposition

- Diverticula

- Bilocular (hourglass) contraction

Surgical Considerations

Some issues of the stomach may require surgery. Some of these problems include stomach cancer, gastric ulcers, tearing, and others. Additional surgical consideration includes bariatric surgeries considered for weight loss involving the stomach such as gastric bypass surgery and gastric banding. Laparoscopic surgery is recommended where applicable and possible to promote minimally invasive access to the stomach and to facilitate quicker recovery time for the patient. Various radiographic techniques can be used for the evaluation of the stomach. Additionally, endoscopes can be used to evaluate stomachs and determine the necessity of surgery or plan for it accordingly.[9][10]

Clinical Significance

Understanding and treating diseases of the stomach are of great clinical significance. Most issues of the stomach, when detected early enough, can be treated to avert the greater destruction of the organ or the patient as a whole. The stomach is a primary digestive organ and an important step in the delivery route of food to the duodenum. As such, issues related to this organ may affect the nutritional wellbeing of a patient by not permitting him or her to receive these essential nutrients by means of this digestive path.

Several issues can occur in relation to the stomach. These issues are of clinical significance. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an issue where stomach acid continuously enters the esophagus from the stomach. GERD patients are commonly present with heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, chronic cough, and hoarseness. It is important to treat GERD because it is a major risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Dyspepsia is an issue where the stomach frequently feels unsettled and the individual experiences indigestion. Gastric ulcers result when stomach acid erodes the inner lining of the stomach. Tumors, bleeding and even stomach cancer can all also occur in the stomach. To remedy many of these issues, where surgery is not needed, various medications are used to target the causes of these issues. Some of these medications include histamines, proton pump inhibitors, and antacids for stomach acid reductions. Motility agents may also be administered to aid stomach muscular contractions and antibiotics may also be used to fight infections of the stomach such as those caused by Helicobacter pylori.