Continuing Education Activity

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is a condition where an unusually significant increase in heart rate accompanies the action of an individual going from lying to standing. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of postural orthostatic tachycardia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the epidemiology of orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

- Explain the pathophysiology of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

- Describe the treatment modalities indicated for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for effective care coordination and provision of patient education to successfully manage postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Introduction

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a common form of autonomic dysregulation characterized as an excessive tachycardia upon standing in the presence of orthostatic intolerance.[1][2][3] Current adult diagnostic criterion requires a heart rate increase of greater than or equal to 30 bpm within the initial 10 minutes of standing or head-up tilt (HUT) in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.[4][5] POTS predominantly affects premenopausal females (5 to 1) between 15 and 50 years of age, manifesting with symptoms of fatigue, headache, palpitations, sleep disturbance, nausea, bloating, among others.[2][6][3] A multitude of pathophysiologic mechanisms including but not limited to disproportionate sympathoexcitation, volume depletion, autoimmune dysfunction, cardiac and physical deconditioning point to a heterogeneously complex etiology.[3][5][7] Most significantly, the debilitating nature of POTS predisposes patients to a high degree of functional impairment and decreased quality of life,[8] emphasizing the need for further investigation into the understanding and management of this increasingly prevalent clinical syndrome.

Etiology

A variety of proposed etiologies have led to the characterization of specific postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome subtypes as described below, with a general consensus of excessive tachycardia in the setting of cardiovascular deconditioning as the final common pathway.[7]

Neuropathic

Neuropathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is a length-dependent autonomic neuropathy characterized by predominantly lower limb sympathetic denervation leading to reduced venoconstriction and venous pooling.[2][5] One study observed 50% of POTS patients exhibited peripheral sudomotor denervation correlated with a distal pattern of anhidrosis demonstrated by thermoregulatory sweat testing.[9] POTS patients have been observed to have decreased norepinephrine spillover in the lower extremities despite normal systemic norepinephrine spillover implicating dysfunctional norepinephrine reuptake due to injured terminal nerves.[10] Peripheral venous pooling evidenced by dependent acrocyanosis has also been observed.[11] Thus, an excessive cardiovascular response is necessary to maintain adequate mean arterial pressures.

Hyperadrenergic

An estimated 30 to 60% of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome patients fall under the hyperadrenergic subtype, characterized by elevated standing plasma norepinephrine levels of greater than or equal to 600 pg/mL with predominant symptoms of increased sympathetic tone including palpitations, tremors, hypertension, anxiety, and tachycardia.[4][5] A norepinephrine transporter (NET) loss of function gene mutation (SLC6A2) resulting in deficient norepinephrine transport contributing to an increased mean supine heart rate was a feature in one case.[12] NET block is more frequently seen in the setting of pharmacologic inhibition by medications including tricyclic antidepressants, sympathomimetics (i.e., methylphenidate), and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (i.e., bupropion).[4][5] These medications are often useful in treating the associated cognitive effects of POTS such as depression, anxiety, and concentration difficulties. Therefore it is prudent to ensure patients are systemically clear of possible pharmacologic causes of elevated catecholamine levels and tachycardia throughout diagnostic evaluations.

Hypovolemic

Up to 70% of patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome exhibit decreased plasma, red blood cell, and total blood volumes, although the degree of hypovolemia varies between studies.[13][5][14] In POTS patients, this physiologic low volume state persists in association with a paradoxically low level of renin and aldosterone levels, suggesting a possible impairment of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis that is crucial to maintaining adequate plasma volume [15]. Secondary hypovolemic states present in patients with co-existing gastrointestinal conditions culminating in excessive fluid loss and poor volume intake (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea).[4]

Autoimmune

An autoimmunity hypothesis is one proposal for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome given the significant overlapping commonalities (female predominance, post-viral onset, elevated autoimmune markers) seen in other systemic autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and Sjogren’s syndrome.[4][6] Previous studies have demonstrated increased autoantibodies in POTS. Positive antinuclear antibodies were present in up to 25% of patients, with Hashimoto thyroiditis being the most prevalent.[1][16] One study demonstrated increased proinflammatory IL-6 levels in POTS patients associated with increased sympathetic drive, perhaps driven by chronic systemic immune activation.[17] Additionally, other autoimmune markers including ganglionic AChR, G-protein coupled receptor, and various nonspecific autoantibodies have presented in the POTS population.[1][3][18]

Deconditioning

Physical and cardiovascular deconditioning is often evident in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, although its presence as either a cause or effect is unclear.[11][13] Moreover, it appears the severity of deconditioning does not necessarily correlate with objective laboratory or autonomic findings.[19] Similar POTS-like symptoms have been observed in otherwise healthy individuals placed in microgravity environments such as space flight, further implicating the physical and gravity dependent roles underlying POTS.[7] Decreased cardiac size and mass have been demonstrated in POTS patients compared to healthy controls, with an average decreased left ventricular mass of 16% and reduced plasma volume of 20%.[20][21] The well documented chronic fatigue, autonomic instability, and overall functional impairment give way to reduced physical activity and prolonged bed rest states, resulting in an unfavorable feedback cycle that exacerbates already prominent existing symptoms.

Epidemiology

As one of the most common forms of orthostatic intolerance globally, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is estimated to affect over 500000 patients in the United States alone.[4][20][22] Worldwide prevalence has not been well-established, although previous study populations have estimated ranges between 0.2 to 1% in developed countries.[1][11] The overwhelmingly demographic of POTS patients are young, premenopausal Caucasian females (4.5 to 1) between the ages of 15 and 45 years old,[1][2][6] with the majority presenting between the ages of 15 and 25 years.[5][6][11][13] There is a significant overlap between POTS, chronic fatigue syndrome and across a spectrum of autoimmune disorders.[3][16]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology underlying postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is heterogeneous, encompassing excess sympathetic tone, impaired peripheral autonomic function, volume dysregulation, cardiovascular deconditioning, and autoimmune dysfunction.[4][5][7][11] In normal healthy subjects, a shift of the intravascular volume to the interstitial space reduces the total effective circulating blood volume, reflecting the gravity-dependent physiology seen in orthostatic-related pathologies. As expected, a subsequent reduction in stroke volume results in a compensatory increased sympathetic drive augmenting cardiac contractility, heart rate, and systemic vascular resistance. POTS patients exhibit persistent decreased stroke volume despite an exaggerated sympathetic response with postural changes such as standing, culminating in a final common pathway of tachycardia in the presence of orthostatic intolerance on standing.[4][7]

The mechanisms as mentioned earlier are not mutually exclusive but instead overlap in a complex interaction of cause and effect. Affected physiologic systems include neuropathic, cardiovascular, renal, immune, and hematologic; this widespread implication of complex systems have added a certain degree of difficulty in constructing a comprehensive framework in the understanding of POTS. Common symptoms include chronic fatigue, dizziness, sleep disturbance, headache, tremors, tachycardia, anxiety, depression, gastrointestinal disturbances, syncope, and vision changes.[1][6][13][22]

History and Physical

The typical POTS patient is a young female between 15 and 25 years old presenting with multiple often chronic symptoms such as fatigue, lightheadedness, palpitations, cognitive impairment, and less commonly syncope.[1][5][13] Autonomic dysfunction often manifests as gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, abdominal pain) and bladder complaints (suprapubic pain, frequency).[11] Additionally, stressors including viral infections, trauma, surgery, and pregnancy have been noted to precipitate symptom onset.[5][11] Family history is not well correlated due to the generalized and chronic nature of the syndrome. It is important to elucidate possible contributing factors such as physical fitness level, sleep hygiene, fluid intake, and current medication or supplement usage.

The physical exam may reveal peripheral edema, acrocyanosis, clammy skin, joint hypermobility, and changes in peripheral sensation.[1][5][6][22] The absence of discrete findings on the physical exam does not preclude the presence of POTS.

Evaluation

The initial evaluation of suspected postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome should focus on excluding primary cardiovascular etiologies such as structural heart defects or tachyarrhythmias, underlying systemic causes including endocrine dysfunction, establishing chronicity of autonomic complaints, medication review, and assessing associated co-morbidities including gastrointestinal, neurological, and psychiatric signs and symptoms.[5]

In addition to a complete history and physical, basic labs and a thorough cardiac evaluation (electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, Holter monitor) should be initiated. The predominance of specific states such as physical deconditioning, gastrointestinal, urologic, and hyperadrenergic symptoms may necessitate additional testing including VO2 max exercise testing, thyroid function panel and autoimmune studies, plasma, and urinary metanephrines, and specialist consultation.[1][4]

An active stand test consists of having the patient lying supine for 10 minutes with measurement of supine baseline blood pressure and heart rate; the patient then stands and with re-measurement of BP and HR at timed intervals (1, 3, 5, and 10 minutes).[4] The head-up tilt table (HUT) with non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring is the accepted gold standard for assessing orthostatic intolerance in POTS.[1] Current adult diagnostic criterion requires a heart rate increment greater than or equal to 30 bpm within the first 10 minutes of standing or HUT in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.[4][5]

Treatment / Management

The management of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome divides into non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches and contingent on accurate diagnosis, patient education, and therapy adherence.

Patient education and management of expectations are crucial to the overall successful management of POTS given its often non-specific and chronic debilitating nature. It is important to assess the patient’s understanding, answer and follow-up on questions and concerns, and emphasize the need for a multi-pronged therapeutic approach to treatment to improve quality of life. There is no current class I recommendations for POTS management.[1][11] Regardless of treatment, each approach should be tailored individually to predominating subtypes (e.g., hyperadrenergic, hypovolemic).

Exercise conditioning is a fundamental aspect of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome treatment (class IIA),[1][11] and it is a recommendation for all patients to start on a gradual physical exercise regimen.[22] Given the high probability of symptom exacerbation with activity, beginning with a supervised low-intensity program focused on avoiding upright positioning (rowing, swimming) with incremental progression over 3 months has been demonstrated to improve symptoms.[4][6][11] A previous progressive 3-month exercise regimen was found to increase maximal oxygen intake 11%, left ventricular mass 12%, end-diastolic volume 8%; at the conclusion, 53% (10/19 patients) no longer met POTS criteria.[20] Other conservative non-pharmacologic interventions include physical counter maneuvers (muscle contraction, leg crossing, forward bending),[5] compression garments, increased fluid (2-3 liters) and salt (slowly up to 10 grams) intake,[7] and avoidance of symptom exacerbation (caffeine, alcohol, prolonged heat exposure).

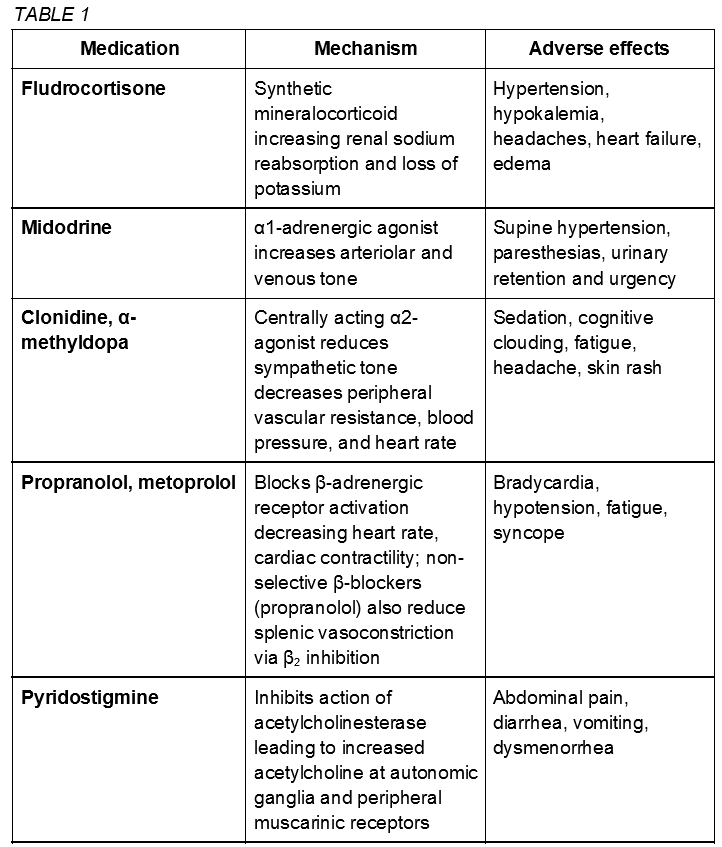

Pharmacologic therapies (class IIb) are not considered first-line treatment for POTS and enter the clinical picture in severe or refractory cases with the goal of stabilization for continued physical reconditioning.[11] POTS medications are not proven to be more effective than non-pharmacologic approaches and should be utilized with caution given potential adverse interactions and side effects. The US Food and Drug Administration has not approved any drug for POTS treatment. The following medications are used off label.[4][22] Some common medications are described here and summarized in table 1.

Fludrocortisone, a synthetic mineralocorticoid aldosterone analog, increases salt retention and plasma volume. Adverse hypertension, hypokalemia, and headaches may be present.

The alpha-1-adrenergic agonist midodrine causes systemic vasoconstriction leading to an increase in venous return that may be effective in hypotensive phenotypes. Limitations include frequent dosing, urinary retention, and supine hypertension.[13]

Clonidine and alpha-methyldopa are central-acting alpha-2 agonist sympatholytics that may be beneficial in hyperadrenergic subtypes with hypertension as a predominant symptom. May cause adverse sedation, cognitive clouding, and fatigue.

Beta-blockers (propranolol, metoprolol) may reduce upright tachycardia without significant hemodynamic changes. However, worsening fatigue is a concern.

Pyridostigmine is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that increases acetylcholine levels in the autonomic ganglia.[11] In turn, this may reduce tachycardia with minimal hemodynamic effects; however worsening cramps, vomiting, and urinary symptoms often limit continued use.

Generally medications exacerbating specific symptoms such as tachycardia (sympathomimetics including amphetamines, selective serotonin and/or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, droxidopa) or worsening orthostatic intolerance (diuretics, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, opiates, tricyclic antidepressants) should be avoided; in specific cases it may be beneficial in accordance with the patient’s history and presentation.[4][22]

Differential Diagnosis

The broad and often non-specific signs and symptoms observed in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome can mimic numerous other disease processes, especially given the systemic nature of the syndrome. It is therefore imperative to obtain a complete history and physical to establish onset, chronicity, family history, medication use in the context of at-risk demographic (young White female), in addition to the above mentioned diagnostic tests.

Significant differential and diagnostic exclusions include but are not limited to: structural heart defects, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, anemia, adrenal insufficiency, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, infectious etiologies, thyroid disease, renal insufficiency, peripheral neuropathies, central dysautonomia, pheochromocytoma, malignancy, epilepsy, anxiety, depression, and adverse medication reactions.

Prognosis

The prognostic outcome for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is favorable, although long-term data is limited. Over half of patients do not meet criteria for POTS within 5 years, most within the first 1 to 2 years, characterized as the absence of orthostatic symptoms with minimal functional impairment.[1][22] Younger patients generally experience more favorable outcomes,[22] with only a sporadic few cases of POTS developing in those over 50 years old.[13] There have no deaths attributed directly to POTS.[6][13]

Complications

There is limited data regarding specific complications arising from postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; however, the impact on the quality of life and daily function may be quite significant. Worsening physical and cardiovascular deconditioning may predispose some individuals to increased rates of infection, thromboembolism in addition to detrimental maladaptive psychological and cognitive processes. Anxiety, depression, and fatigue often persist despite treatment, perhaps revealing a therapeutic avenue for cognitive and behavioral approaches.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As described above, patient education remains a cornerstone in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome management. Information regarding differentiation and attribution of symptoms, alleviating and exacerbating factors, combination treatment modalities, and focus on daily functional improvement must be presented in a clear manner. As with many chronic conditions, establishing a favorable physician-patient rapport via timely follow up, close monitoring, and if needed specialty consultation is key to therapeutic adherence and overall recovery.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a common form of autonomic dysregulation predominantly affecting young White females characterized by excessive tachycardia upon standing in the presence of orthostatic intolerance.

- Adult diagnostic criteria require a heart rate increase of greater than or equal to 30 bpm within the first 10 minutes of standing or head-up tilt (HUT) in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

- The complex heterogeneous etiologies of POTS generally classify as neuropathic, hyperadrenergic, hypovolemic, autoimmune, and physical deconditioning with significant overlap between the various etiologies.

- Symptoms are often chronic and non-specific and may include chronic fatigue, dizziness, sleep disturbance, headache, tremors, tachycardia, anxiety, depression, gastrointestinal disturbances, syncope, and vision changes.

- Management and treatment require an emphasis on patient education, and a progressive monitored exercise regimen with second-line pharmacologic approaches aimed at increasing fluid volume and controlling excessive sympathetic drive (fludrocortisone, midodrine, clonidine, propranolol).

- Prognosis is favorable especially with younger age at onset, with more than half of patients no longer meeting POTS criteria within 5 years.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome is a complex, heterogeneous disease that requires a multimodal, interprofessional approach to effective management. The presentation of nonspecific and often chronic symptoms that overlap neurological, cardiovascular, and autoimmune domains makes diagnosis itself a significant challenge; therefore, initiating appropriate treatment designed to address pertinent subtypes may at times be more burdensome. Patient education is essential for establishing expectations and treatment compliance.

A recent 2016 study evaluating 33 adolescents with confirmed POTS who underwent a 3-week an interprofessional rehabilitation program consisting of physicians, physical and occupational therapists, psychologists, and nurses saw significant reductions in psychological stress and functional impairment (class IIb).[23]

As noted above, no current class I recommendations exists for the management of POTS, although exercise rehabilitation is considered an integral aspect of treatment (class IIa). Physical rehabilitation therapists play a crucial role in this regard, and dieticians may alleviate a significant burden of creating and maintaining a cardiovascularly healthy nutritional plan. The ongoing cognitive and psychological disruption experienced by many POTS patients often necessitates establishing a trusting, long-term rapport between the patient and healthcare team, and continuous psychological evaluation and therapy have been demonstrated to improve overall outcomes. Also, pharmacist-directed medication management would impart a significant benefit especially in more serious, refractory cases.

More investigation is still necessary into the complex pathophysiology and treatment of POTS. A collaborative an interprofessional approach should be encouraged and personalized for all patients to alleviate the significant physical, psychological, and functional impairment of POTS.

Diagnosis and management of POTS require a collaborative effort from an interprofessional team, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nursing staff, and pharmacists, communicating effectively to bring about optimal patient outcomes. [Level V]