Continuing Education Activity

Umbilical vein catheterization utilizes the exposed umbilical stump in a neonate as a site for emergency central venous access up to 14 days old. Umbilical vein catheterization can provide a safe and effective route for intravenous delivery of medications and fluids during resuscitation. This activity reviews umbilical vein catheterization and the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients who undergo umbilical vein catheterization.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications and contraindications for umbilical vein catheterization.

- Describe the technique of umbilical vein catheterization.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of the potential complications of umbilical vein catheterization.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance umbilical vein catheterization and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Umbilical vein catheterization utilizes the exposed umbilical stump in a neonate as a site for emergency central venous access up to 14 days old. Umbilical vein catheterization can provide a safe and effective route for intravenous delivery of medications and fluids during resuscitation. While most commonly used in the delivery room for resuscitation, the umbilical vein presents a viable point of venous access for a trained provider. While peripheral intravenous access is the preferred route of administration of medications in the neonate, providers who care for neonates should be skilled in multiple techniques for IV access, including intraosseous lines, peripheral IVs, central venous catheters, and umbilical vein access. While intraosseous (IO) access has shown to be more quickly attainable than an umbilical vein catheter in a neonate, difficulty placing an IO in a neonate and risk of dislodgement during a code make umbilical vein catheterization an attractive modality for intravenous access by personnel trained in the procedure.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

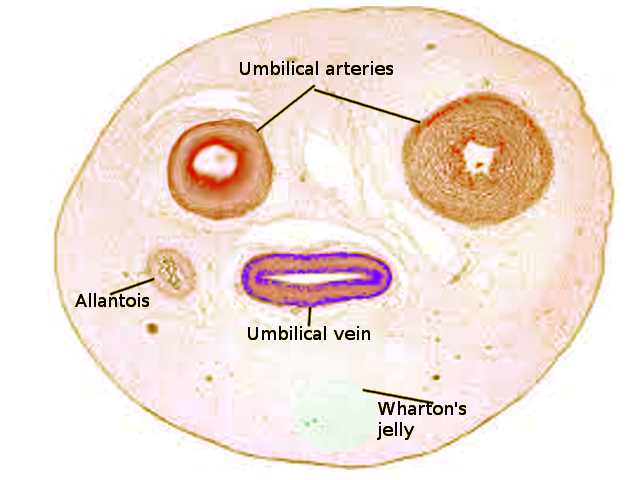

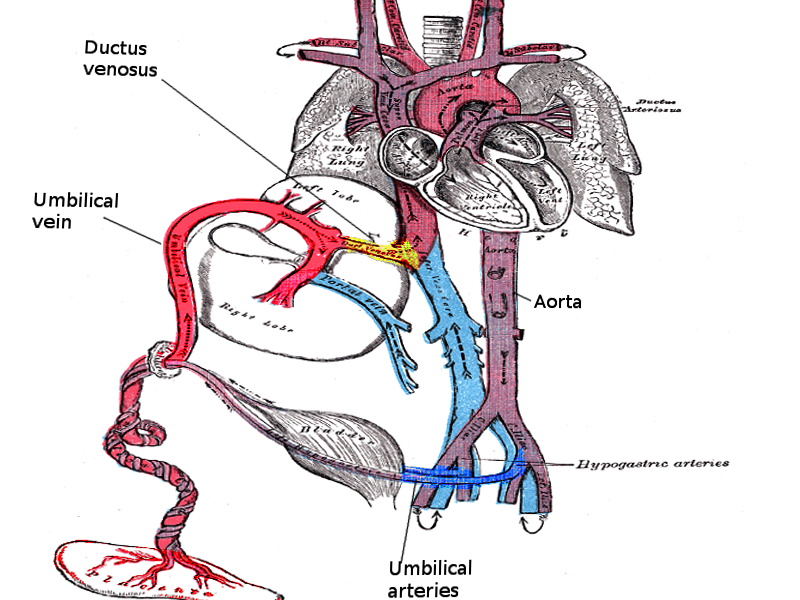

The umbilical cord develops from the yolk sac and allantois during the fifth week of development. It remains roughly equal in size to the crown-rump length through pregnancy. At birth, the cord is, on average, 2 centimeters in diameter and 50 centimeters in length and must be clamped and cut. The umbilical cord has two umbilical arteries and one umbilical vein. The umbilical arteries are recognizable by their smaller lumen and thick walls. The umbilical vein is normally present at 12 o’clock and has a thinner wall and a larger lumen than the arteries. A catheter placed in the umbilical vein should travel from the umbilical vein into the ductus venosus and ideally terminate in the inferior vena cava just below the right atrium.[2]

Indications

The indication for umbilical vein catheterization is when there is a need for IV access in a neonate for resuscitation, transfusions, or short-term venous access when access is otherwise unobtainable.

Moreover, according to a consensus guideline released by McMaster University, the use of UVCs was recommended in the following groups; 1. all preterm infants with a gestational age of equal or less than 28 weeks, and 2. in newborns of equal or greater than 29 weeks of gestational age, mechanically ventilated or with FiO of greater than 40% on continuous positive airway pressure, 3. in newborns of equal or greater than 29 weeks of gestational age who are hemodynamically unstable.[3]

Contraindications

The placement of umbilical vein catheters should is not an option in patients with gastroschisis, omphalitis, omphalocele, peritonitis, vascular compromise, and necrotizing enterocolitis.

Equipment

- Radiant warmer

- Sterile gown, sterile gloves, cap, and mask

- Sterile drapes

- Bactericidal solution

- Umbilical tape

- Scissors

- Scalpel

- Iris forceps

- Non-toothed forceps

- Umbilical vein catheter

- Three-way stopcock

- IV tubing

- Needle driver

- 3-O silk suture

- Sterile saline flush

Catheter Sizes:

- Umbilical vein catheters should be selected considering the infants' body weight (3.5 French for infants with less than 3.5 kg body weight, and 5 French for infants with equal or greater than 3.5 kg) flushed with normal saline and attached to a 10-cc syringe using a three-way stopcock.[4][5][6]

Personnel

A physician, resident physician, or advanced practice provider with training in placing an umbilical vein catheter should perform the procedure. A second individual, such as a nurse or medic, should also be present to help monitor the patient throughout the process and provide assistance with positioning and supplies.

Preparation

Equipment, as listed above, should be obtained and inspected. Appropriate lab work, if available, requires review. Written consent is necessary from the parent/guardian of the neonate after a discussion of the risks, benefits, and alternatives of this procedure if not performing the procedure emergently. A time-out should be performed with particular attention to assure that the correct patient is identified and to assess for any contraindications for the procedure. The procedure should take place inside a radiant warmer to avoid environmental exposure to the infant. Flush the catheter with heparinized saline to ensure there is no air present in the catheter and to prevent clotting. Attach a three-way stop-cock to the catheter.

Technique or Treatment

After donning sterile attire as discussed above, the umbilical stump should undergo preparation with a bactericidal solution and a loop of umbilical tape placed at the junction of the skin and umbilical stump. Drape the procedural field with sterile drapes. Grasp the umbilical stump with non-toothed forceps and apply upward traction to straighten the umbilical stump. Take a scalpel and make a transverse cut completely through the umbilical stump 1 to 2 cm from the skin to expose the non-dried umbilical cord to aid in anatomical identification and cannulation of the umbilical vein. Identify the two umbilical arteries by their thicker walls and the umbilical vein by their position at 12 o’clock and their larger thin-walled appearance. Umbilical tape may be tightened to control bleeding if present. Gently use the iris forceps to cannulate and dilate the umbilical vein and to clear any thrombus present in the umbilical vein. Grasp the umbilical vein catheter with the iris forceps and gently introduce the catheter into the umbilical vein. The base of the umbilicus should be held with the non-dominant hand. The flushed umbilical vein catheter (UVC) should be inserted into the vein. The depth of insertion should differ based on the infant's maturity. That said, it should be inserted approximately 3 to 5 cm, and 2 to 4 cm in a full-term and a premature infant, respectively, and check for blood return. The precise catheter tip location should be at the point of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and right atrium confluence.[2]If the clinician meets resistance, loosen the umbilical tape and attempt to advance the catheter again with gentle pressure. If the significant resistance is still present after loosening the umbilical tape, abandon the procedure and seek an alternative method of intravenous access. If the line placement is for emergency access, advance the catheter 1 to 2 cm past the point of initial blood return in the catheter, which is usually 4 to 5 cm in a full term.[7] If the line placement is for more long-term access, the line should be advanced into the inferior vena cava just beneath the right atrium, which is usually 10 to 12 cm in a full-term neonate.

A catheter in the inferior vena cava is considered a central venous catheter and is appropriate for central venous pressure monitoring or infusing medications with a high concentration of glucose or hyperalimentation solutions. If inferior vena cava placement is the intent, the line must be confirmed with X-ray imaging to be above the diaphragm but below the right atrium before use to avoid complications. Numerous standardized graphs and formulas exist to aid in estimating placement depth based on birth weight, shoulder to umbilicus distance. Anatomic landmark-guided methods have been shown to be able to predict insertion length accurately.[8] If placing an umbilical venous catheter for central venous access, follow the institutional guidelines and policies on placement depth. Upon placement of the catheter and the sterile field is taken down, the line may only be withdrawn and not advanced. Secure the catheter using a suture through the cord. After suturing the catheter in place, use tape to create a tape bridge between the abdomen and the catheter for extra protection against displacement. Place a transparent dressing over the umbilical stump and umbilical venous catheter. The accurate catheter tip position should be verified with either a thoracoabdominal x-ray or abdominal sonography. However, abdominal sonography is currently the preferred measure.[2]

Complications

As with all central venous access, the complications of placement include uncontrolled bleeding, infection, damage to adjacent structures, thrombosis, and placement into an artery.[9] Specific to umbilical vein catheters is the risk of placement into the portal venous system, which can lead to hepatic necrosis if hyperosmotic solutions are extravasated.[10] Reports also describe liver abscess, portal vein thrombosis, and cavernoma formation.[11] Due to the small volume of the neonate’s venous system, central lines must be flushed with saline to assure no air is present in the line to prevent air embolism. Inadvertent placement in the umbilical artery can lead to catheter occlusion of limb arterial supply or thrombosis, leading to limb ischemia. Placement into the right atrium can lead to perforation and subsequent pericardial effusion.[12] In a neonate who becomes hemodynamically unstable following placement of an umbilical vein catheter, cardiac tamponade is a consideration.[13] Overall the complication rate of umbilical venous catheters is similar to that of percutaneously placed central venous catheters.[14] Reports indicate significantly lower rates of thrombosis and iliofemoral vein occlusion with umbilical vein catheters compared to femoral central venous catheters.[15]

Clinical Significance

Umbilical vein catheterization remains a reliable form of emergency intravenous and central venous access in neonates up to 14 days old.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An umbilical vein catheterization is a unique form of intravenous access that can be considered by the healthcare team when caring for a neonate. Physicians, residents, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners may place umbilical vein catheters this the help of the nursing staff. In critically ill neonates, decisions about central venous access may require discussion between critical care providers and emergency personnel. Unique aspects of care of umbilical catheters require review between nurses, medics, and advanced providers. Neonatal ICU specialty-trained nurses should assume a significant role in the interprofessional healthcare team performing umbilical vein catheterization, preparing the patient, assisting during the procedure, and caring and monitoring the neonate afterward while administering necessary medications. This approach will lead to better patient outcomes. [Level 5]

This activity cites levels of evidence 2 to 5. There does not appear to be any level 1 data available at the time of writing.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Umbilical vein catheterization requires assistance from several professionals, including the nurse. The nurse not only ensures that consent has been obtained but prepares the kit for catheterization. After inserting the line, an X-ray of the abdomen is abdomen before use; it is the nurse's responsibility to ensure that the line is not used before verification of the X-ray unless it is a dire emergency. Finally, the nurse is in charge of dressing changes and ensuring the site is always clean and dry.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Once an umbilical vein catheterization has occurred, the nurse should ensure that all infusions take place in an aseptic manner. The wound site dressings have to be changed regularly, and the stump site requires observation for bleeding. If there is any change in the functioning of the line, nursing should report it to the physician.