Introduction

The superior mesenteric artery is the second major branch of the abdominal aorta. It originates on the anterior surface of the aorta at the level of the L1 vertebrae, approximately 1 cm inferior to the celiac trunk and superior to the renal arteries. Anterior to the superior mesenteric artery lies the pylorus of the stomach, the neck of the pancreas, and the splenic vein. Posterior to the artery lies the uncinate process of the pancreas, the inferior portion of the duodenum, and the left renal vein. The left renal vein courses directly between the aorta and the takeoff of the superior mesenteric artery. This artery provides blood flow to the third portion of the duodenum, the jejunum, the ileum, the cecum, the ascending colon, and the proximal of the transverse colon.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

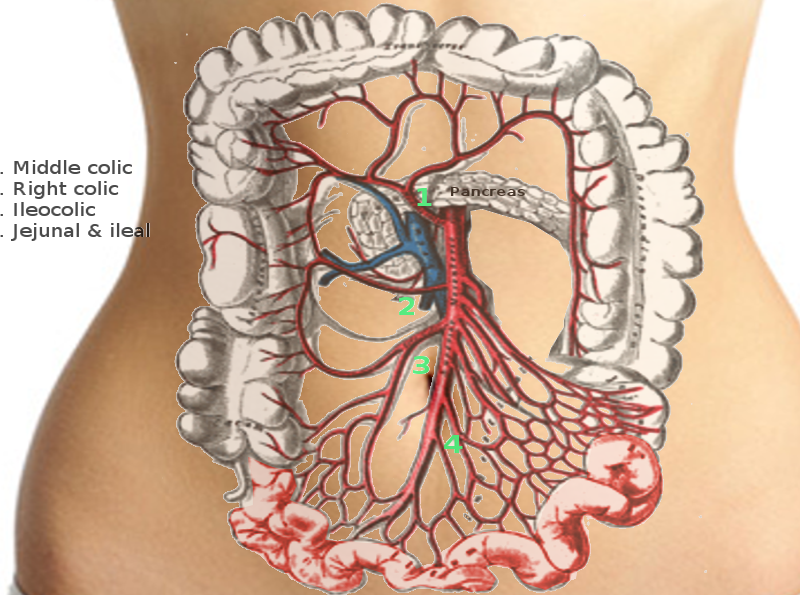

The superior mesenteric artery supplies the midgut from the ampullary region of the second part of the duodenum to the splenic flexure of the large intestine. The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery arises from the SMA and, along with the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, supplies the head of the pancreas.

Marginal Artery of Drummond

The distal branches of the superior mesenteric artery (right colic, ileocolic, and middle colic) and the inferior mesenteric artery (sigmoid and left colic) supply the colon. They are also connected to each other by an intricate arterial arcade along the mesenteric border known as the Marginal Artery of Drummond. This arcade of blood vessels is a normal vascular structure in many healthy people, but it may be absent in others. The marginal artery of Drummond is clinically important because it serves as a collateral supply to the colon when there is a blockage in one of the mesenteric vessels. In people who do not have the marginal artery of Drummond, an ischemic event can lead to bowel infarction and necrosis.

Embryology

During embryogenesis, the paired ventral segmental arteries come close to one another in the midline in the mesentery. Some of the vessels fuse together to form the median vessel, and this eventually results in a three vessel visceral arterial system. This system includes the celiac trunk and the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. The superior mesenteric artery is derived from the omphalomesenteric artery and a special segmental artery.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The first branch of the superior mesenteric artery is the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. This artery bifurcates into anterior and posterior branches, both of which form anastomoses with branches of the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery (a branch of the celiac artery). The inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery supplies the head of the pancreas and the duodenum.

The superior mesenteric artery then gives off several jejunal and ileal arteries to the left, and the middle colic, right colic, and ileocolic arteries to the right. The jejunal and ileal arteries form anastomotic arcades within the mesentery, from which small, straight end arteries called vasa recta supply the intestinal wall. The jejunal blood supply consists of a few arterial arcades with numerous long vasa recta. The ileal blood supply contains more arterial arcades with fewer, shorter vasa recta.

The middle colic artery supplies the transverse colon, while the right colic artery supplies the ascending colon. The ileocolic artery is the inferior most branch of the superior mesenteric artery and supplies the ascending colon, appendix, cecum, and ileum.

The major anastomosis between the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries is the marginal artery of Drummond, supplying the splenic flexure. A more proximal anastomosis between the two is formed via the Arc of Riolan, also known as the meandering artery. It is typically an arterial anastomosis between the middle colic artery, which is a branch of the superior mesenteric artery, and the left colic artery, a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery.[4]

Surgical Considerations

The superior mesenteric artery can be stenosed or become narrowed leading to acute mesenteric ischemia. If not recognized it can lead to gangrene of the bowel. The superior mesenteric artery may develop low flow as a result of hypotension from any cause, or it may be become occluded as a result of atherosclerosis or an embolus.[5][6][7][8]

An acute mesenteric arterial embolism is of myocardial origin in most cases. Classic causes include atrial thrombi, mural thrombus following a myocardial infarct, atrial fibrillation, mycotic aneurysms, or thrombi from atherosclerotic plaques.

Arterial thrombosis of the superior mesenteric artery is usually due to visceral atherosclerosis. Symptoms typically do not appear until all the branches of the mesenteric artery are blocked. The thrombus results in a gradual decrease in blood flow and over time the patient develops abdominal pain after eating. If not recognized, the bowel can become necrotic. Elevated serum lactate may be found due to bowel ischemia. Emergent CT Angiogram of the abdomen is indicated if one suspects acute mesenteric ischemia.

Treatment options for acute thrombosis include open surgery, percutaneous angioplasty, and stenting or thrombolytic therapy. The condition carries very high mortality if there is a delay in treatment.[9][10]

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia results in decreased perfusion of the bowel. It may be due to septic shock, a myocardial infarct, hypovolemia, or the use of high doses of vasopressors which can cause vasoconstriction.

Clinical Significance

The marginal artery, also known as the artery of Drummond, supplies the proximal descending colon at the splenic flexure. The artery of Drummond is an arterial arcade formed by an anastomosis between the distal branches of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. This anastomosis is often weak and tortuous, or may even be absent. Thus the splenic flexure is a watershed area that is prone to ischemia and infarction in the setting of hypoperfusion.

Sudden occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery causes acute mesenteric ischemia, a surgical emergency that carries a high mortality rate.

The left renal vein can be compressed between the angle formed by the superior mesenteric artery and the abdominal aorta, resulting in nutcracker syndrome. Symptoms may include hematuria, abdominal pain, and left testicular pain in men or left lower quadrant pain in women. These symptoms are due to the occlusion of the left gonadal vein, which drains into the left renal vein.

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome occurs when the third and fourth portions of the duodenum become compressed between the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. Its symptoms include early satiety, nausea, vomiting, and sharp postprandial abdominal pain due to small bowel obstruction.[11]

Other Issues

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, also known as Wilkie syndrome, is a rare disorder that results in compression of the vessel. It is believed that there is an acute angulation of the superior mesenteric artery which results in compression between the third part of the duodenum and the abdominal aorta. The syndrome is known to occur in patients with low body weight, most notably young children.[11]

Dissection of the superior mesenteric artery is a rare, but severe condition that has been reported. It presents with severe abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea and is often confused with acute mesenteric ischemia. It is most commonly found on CT angiogram of the abdomen. There is no consensus opinion on the ideal management of superior mesenteric artery dissection. Options include surgery, interventional radiology placement of a stent, or conservative management.[12]