Continuing Education Activity

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is a type of cerebrovascular disorder characterized by the accumulation of amyloid beta-peptide within the leptomeninges and small to medium-sized cerebral blood vessels. This disorder can have severe morbidity and mortality if it is not identified and treated promptly. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

- Outline the management options available for cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

- Summarize the importance of the interprofessional team to improve outcomes for patients affected by cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

Introduction

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a type of cerebrovascular disorder characterized by the accumulation of amyloid beta-peptide within the leptomeninges and small/medium-sized cerebral blood vessels.[1] The amyloid deposition results in fragile vessels that may manifest in lobar intracerebral hemorrhages (ICH). It may also present with cognitive impairments, incidental microbleeds, hemosiderosis, inflammatory leukoencephalopathy, Alzheimer disease, or transient neurological symptoms.[2] It can occur in certain familial syndromes or can occur sporadically. Diagnosis is primarily made through a combination of clinical, pathological, and radiographic findings. However, a definitive diagnosis requires a postmortem examination of the brain. Currently, there are no disease-modifying treatments available. Prognosis is dependent on CAA presenting features, with worse outcomes in patients with large hematomas and older age.

Etiology

The exact etiology of cerebral amyloid angiopathy is not fully understood. CAA is characterized by congophilic material (amyloid-beta peptide) being deposited into the leptomeninges and small to medium-sized cerebral blood vessels. This deposition weakens vessel walls, making them prone to bleeding. CAA can occur in certain familial syndromes or can occur sporadically.

Familial CAA

Cases of “presenile” CAA are caused by mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene.[3] Examples of other mutations resulting in familiar CAA include ACys peptide, ATTR peptide, PrPSc peptide, ABri peptide, ADan peptide, and AGel peptide.

Sporadic CAA

In the older patient population, the factors that result in amyloid beta-peptide deposition are not well understood. Some evidence has demonstrated a relationship with apolipoprotein E (APOE). Researchers found that patients with APOE epsilon 2 or epsilon 4 alleles seem to be at a greater risk for cranial hemorrhages than the general population.[4]

Epidemiology

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is strongly age-dependent, with the prevalence of moderate to severe CAA increasing with age. Sporadic CAA uncommonly affects individuals younger than 60 to 65 and even rarer for those in their 50s. CAA does not appear to have a predilection for gender. There is a possible association between hypertension and CAA, but this is disputed between experts.

History and Physical

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is usually asymptomatic in individuals. However, when symptomatic, the most common clinical manifestation is spontaneous lobar hemorrhage. The location and the size of the hemorrhage largely determine the clinical deficits. Those extending towards the ventricles may cause hemiplegia and decreased consciousness, while smaller hemorrhage may cause more focal deficits, headaches, or seizures. Interestingly, very small hemorrhages may be asymptomatic. The hemorrhage location often reflects the distribution of the amyloid-beta peptide, favoring the cortical vessels. The hemorrhages are more likely to occur in the posterior brain. The cerebellum commonly contains vascular amyloid accumulation (primarily the cerebellar cortex and vermis).

Cognitive impairment has also been described as a presenting symptom. Three patterns have been described:

- Gradual decline - microhemorrhages, lobar lacunas, microinfarcts, ischemic leukoencephalopathy

- Step-wise decline - recurrent lobar hemorrhages

- Rapidly progressive decline - cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation

Evaluation

The Boston criteria are commonly used when evaluating patients for Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. It is a combination of clinical, pathological, and radiographic criteria that are used to assess the probability of CAA. Definitive diagnoses can only be made through a postmortem examination of the brain. However, a “probable CAA” diagnosis can be made during life utilizing imaging or tissue sampling.

Modified Boston Criteria

- Definite CAA (postmortem) – postmortem examination demonstrating:

- Lobar, cortical-subcortical hemorrhage, or cortical hemorrhage

- Absence of another diagnostic lesion

- Severe CAA with vasculopathy

- Probable CAA (with pathology)- clinical data and pathologic tissue demonstrating:

- Lobar, cortical-subcortical hemorrhage, or cortical hemorrhage

- Pathological evidence of CAA

- Absence of another diagnostic lesion

- Probable CAA (with imaging) – clinical data and imaging demonstrating:

- Multiple hemorrhages restricted to the cortical, lobar, or cortical-subcortical regions or

- Single lobar, cortical, or cortical-subcortical hemorrhage and focal or disseminated superficial siderosis

- Absence of another diagnostic lesion

- Age ≥55 years

- Possible CAA (with imaging) - clinical data and imaging demonstrating:

- Single hemorrhage restricted to the cortical, lobar, or cortical-subcortical region. Or diffuse, superficial siderosis

- Absence of another diagnostic lesion

- Age ≥55 years

Imaging

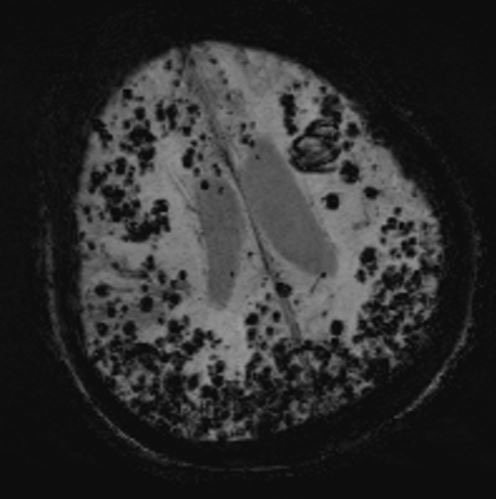

Gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is one of the most important techniques used for diagnosis. Gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates regions of low-signal blooming artifact caused by iron depositions left by old hemorrhages. Another very useful technique is a susceptibility-weighted MRI (more sensitive than gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)). Using these techniques, multiple areas of hemorrhage can be identified to help support the diagnosis of CAA.[5]

Pathology

Brain biopsies are rarely utilized in the diagnosis of CAA, except when CAA-related inflammation is suspected. If a sample is obtained, it should be examined with beta-amyloid immunostain or Congo red stain. Using these techniques, the deposition of amyloid beta-peptide can be identified to help support the diagnosis of CAA.[6]

Treatment / Management

Management is often based on presenting symptoms. Acute management of patients with an ICH is similar to other spontaneous ICH. Attention to blood pressure and intracranial pressure is essential. When surgical intervention is performed, the mortality risk is largely unchanged when compared to other types of ICH. The factors that are associated with a worse prognosis are intraventricular hemorrhage and age greater than equal to 75.

ICH associated with CAA is frequently recurrent. Because of this high rate, clinicians typically avoid antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants when a strong indication for anticoagulation is not present. Notably, there have been studies demonstrating benefits in restarting anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation.[7]

Blood pressure control has also been associated with mortality benefits, even though CAA does not seem to be largely driven by hypertension.[8] The PROGRESS trial demonstrated a risk reduction of 77% for CAA-related ICH when blood pressure was controlled. The observation supports these findings that lower ambulatory blood pressure resulted in a reduced risk of ICH recurrence.

Lastly, limited evidence has shown benefits in utilizing immunosuppression for the treatment of the inflammatory forms of CAA. Small trials have shown pulsed cyclophosphamide or glucocorticoids resulted in sustained clinical improvement. Other immunosuppressive medications have also been associated with benefits, including mofetil, mycophenolate, and methotrexate.[9]

Differential Diagnosis

Nontraumatic ICH includes:

- Hemorrhagic tumor

- Hemorrhagic transformation of an ischemic stroke

- Lobar extension of a hypertensive putaminal hemorrhage

- Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

Other imaging differential diagnosis includes:

- Hypertensive microangiopathy

- Hemorrhagic metastases

- Multiple cavernoma syndrome

- Diffuse axonal injury

- Radiation-induced vasculopathy

- Neurocysticercosis

Prognosis

The prognosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy can be variable but is largely determined by the location and size of the ICH. Unfavorable outcomes are associated with larger hematoma size and the age of the patient (≥75). Favorable ICH outcomes are associated with sparing of the ventricles and a superficial location. Mortality ranges from 10% to 30%, with the best prognosis seen in patients with increased consciousness and smaller hematomas (<50 mL). CAA has a high hemorrhage recurrence risk when compared to a hypertensive hemorrhage. Studies have revealed recurrence rates of around 21%.[10]

CAA is commonly associated with both transient and cognitive neurological impairment. Transient neurological symptoms are characterized by brief, recurrent spells of numbness, paresthesias, and weakness. The pathogenesis is not fully understood, but symptoms are typically only transient. At the same time, the cognitive impairments have revealed diminished cognitive speed and episodic memory loss. Interestingly, Alzheimer disease and CAA frequently coexist. CAA has also been found to correlate with vascular dementia.[11]

Complications

Besides the ICH, Cerebral amyloid angiopathy has many other complications:

- Transient neurologic symptoms

- Microbleeds

- Cortical superficial siderosis

- CAA-related inflammation

- Cognitive impairment

Deterrence and Patient Education

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a type of cerebrovascular disorder characterized by the accumulation of amyloid within the leptomeninges and small/medium-sized cerebral blood vessels.[1] The amyloid deposition results in fragile vessels that may manifest in brain bleeds. It may also present with cognitive impairments, incidental microbleeds, hemosiderosis, inflammatory leukoencephalopathy, Alzheimer's disease, or transient neurological symptoms.[2] It can occur in certain familial syndromes or sporadically. Diagnosis is primarily made through a combination of clinical, pathological, and radiographic findings. Currently, there are no disease-modifying treatments available. Prognosis is dependent on CAA presenting features, with worse outcomes in patients with large hematomas and older age.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of patients with Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is best when using an interprofessional team that includes primary care doctors, neurosurgeons, radiologists, and pathologists. Stroke-trained nurses, physical therapists, and pharmacists should also assist in the case. The patient most often will present to the emergency department in the setting of stroke symptoms. Utilizing clinical and radiographic findings, the probability of CAA can be assessed. Treatment of ICH is similar to other spontaneous ICH, possibly requiring intervention from neurosurgery. Attention to blood pressure and intracranial pressure by the staff is essential. If there is residual impairment, rehabilitation is essential to regain mobility and function. The pharmacist may manage the pain and help with the appropriate use of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants. Long-term follow-up is essential to evaluate for reoccurrence and functional status. If CAA is thought to be familial CAA, further workup can be perused in an outpatient setting. Open communication between the interprofessional is essential for improving outcomes.