Continuing Education Activity

A cephalohematoma is an accumulation of blood under the scalp, specifically in the sub-periosteal space. During the birthing process, shearing forces on the skull and scalp result in the separation of the periosteum from the underlying calvarium resulting in the subsequent rupture of blood vessels. This activity reviews the workup of cephalohematomas and describes the role of health professionals working together to manage this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology of cephalohematoma.

- Describe the clinical presentation of cephalohematoma.

- Summarize the treatment of cephalohematoma.

- Outline the evaluation of cephalohematomas and describe inter-professional management of this condition.

Introduction

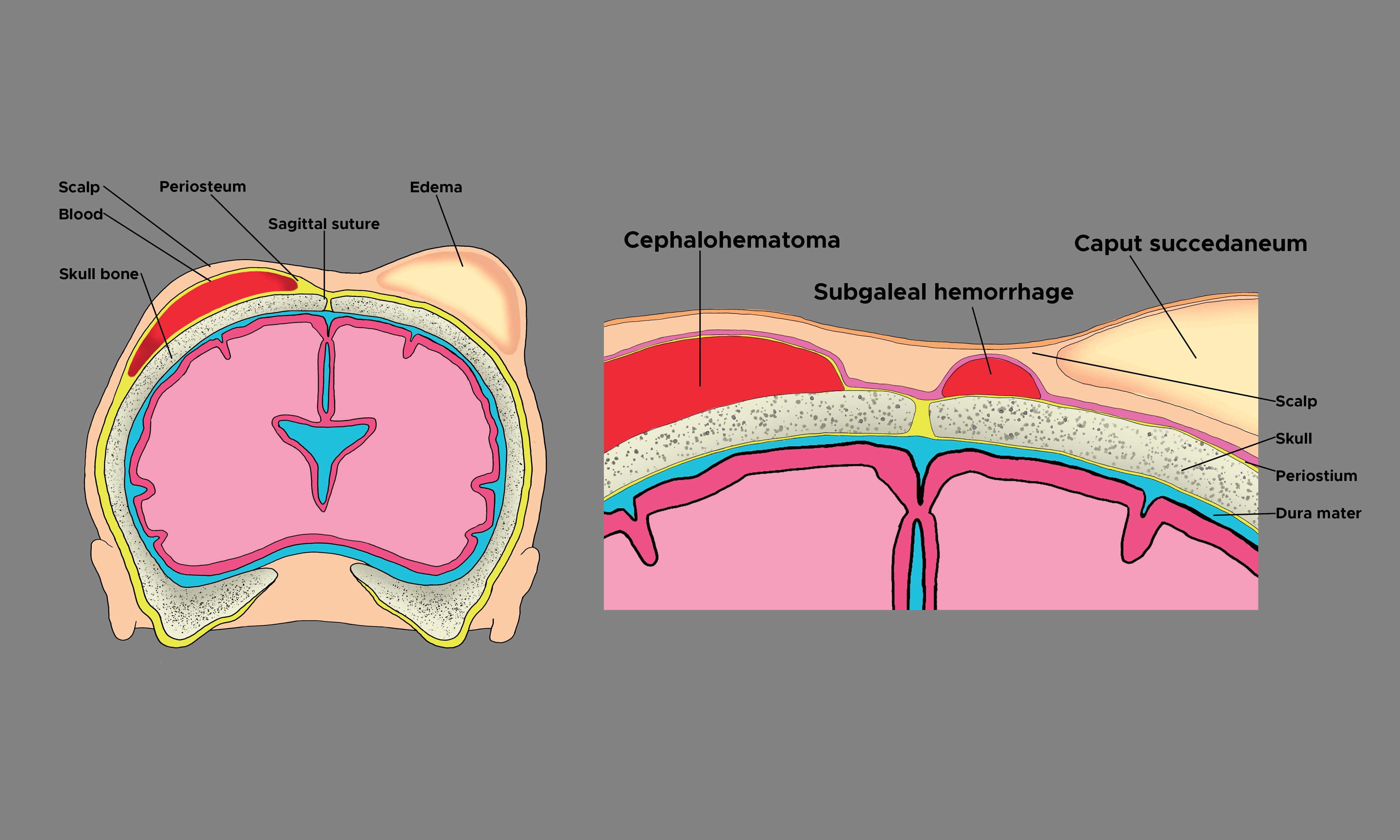

A cephalohematoma is an accumulation of subperiosteal blood, typically located in the occipital or parietal region of the calvarium.[1][2][3] During the birthing process, shearing forces on the skull and scalp result in the separation of the periosteum from the underlying calvarium, resulting in the subsequent rupture of blood vessels.[2] The bleeding is gradual; therefore, a cephalohematoma is typically not immediately evident at birth. [4][5][6] A cephalohematoma instead develops during the following hours or days after birth, with the first one to three days of birth being the most common age of presentation.[1] Because the cephalohematoma is deep to the periosteum, the boundaries are defined by the underlying calvarium. In other words, a cephalohematoma is confined and does not cross the midline or calvarial suture lines.

Cephalohematomas may rarely occur in juveniles or adults following trauma or surgery.[2]

Etiology

The etiology of cephalohematoma is the rupture of blood vessels crossing the periosteum due to the pressure on the fetal head during birth. During the birthing process, pressure on the skull from the rigid birth canal or the use of ancillary external forces such as forceps or a vacuum extractor can result in the rupture of these small and delicate blood vessels resulting in the collection of sanguineous fluid.[7] Factors that increase pressure on the fetal head and ultimately increase the risk of the neonate developing a cephalohematoma include:

- A prolonged second stage of labor

- Macrosomia, or increased size of the infant relative to the birth canal

- Weak or ineffective uterine contractions

- Abnormal fetal presentation

- Instrument-assisted delivery with forceps or vacuum extractor

- Multiple gestations

- Presentation of occiput in transverse or posterior position during delivery

- Cesarean section was initiated following the first stage of labor

The above-listed factors contribute to the traumatic impact of the birthing process on the fetal head. Aside from the birthing process, cephalohematoma may rarely occur in adults or juveniles following trauma or surgery.[2]

Epidemiology

Cephalohematoma is a subperiosteal accumulation of blood that occurs with an incidence of 0.4% to 2.5% of all live births.[3] For unknown reasons, cephalohematomas occur more often in male than in female infants.[8]

The lowest incidence of cephalohematoma occurs in unassisted vaginal delivery (1.67%).[9] Cephalohematomas are more common in primigravidae, large infants, infants in an occipital posterior or transverse occipital position at the start of labor, and following instrument-assisted deliveries with forceps or a vacuum extractor.[3] Amongst instrument-assisted deliveries, cephalohematomas occur most commonly following vacuum-assisted delivery (11.17% of deliveries), in comparison to forceps-assisted and cesarean delivery (6.35%).[10][9] A cesarean section that is initiated before the commencement of natural labor, however, is not associated with cephalohematoma.[3]

Pathophysiology

Cephalohematoma is a condition that most commonly occurs during the birthing process and rarely in juveniles and adults following trauma or surgery. External pressure on the fetal head results in the rupture of small blood vessels between the periosteum and calvarium. External pressure on the fetal head is increased when the head is compressed against the maternal pelvis during labor or from additional applied external forces from instruments such as forceps or a vacuum extractor that may be used to assist with the birth. Shearing action between the periosteum and the underlying calvarium causes slow bleeding. As blood accumulates, the periosteum elevates away from the skull. As the bleeding continues and fills the subperiosteal space, pressure builds, and the accumulated blood acts as a tamponade to stop further bleeding.

History and Physical

A comprehensive history of labor and birth is needed to identify newborns at risk of developing cephalohematoma. Factors that increase pressure on the fetal head and the risk of developing a cephalhematoma include:

- A prolonged second stage of labor

- Macrosomia, or increased size of the infant relative to the birth canal

- Weak or ineffective uterine contractions

- Abnormal fetal presentation

- Instrument-assisted delivery with forceps or vacuum extractor

- Multiple gestations

- Presentation with occiput in transverse or posterior position during delivery

- Cesarean section was initiated following the first stage of labor

Because of the slow nature of subperiosteal bleeding, cephalohematomas usually are not present at birth but instead become most noticeable within the first one to three days following birth. Therefore, repeated inspection and palpation of the newborn’s head is necessary to identify the presence of a cephalohematoma. Ongoing assessment to document the appearance of a cephalohematoma is important. Once a cephalohematoma is present, assessing and documenting changes in size is continued. Patients may initially present with a firm but increasingly fluctuant area of swelling over which the scalp moves easily.[2] A firm, enlarged unilateral or bilateral bulge on top of one or more bones below the scalp characterizes a cephalohematoma. The raised area cannot be transilluminated, and the overlying skin is usually not discolored or injured. Cranial sutures define the boundaries of the cephalohematoma. The parietal or occipital region of the calvarium is the most common site of injury, but a cephalohematoma can occur over any of the cranial bones.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of cephalohematoma is largely a clinical one. Diagnosis is based on the characteristic bulge on the newborn's head that does not cross cranial suture lines. The bulge may be initially firm and become more fluctuant as time passes. In contrast to caput succedaneum and subgaleal hematoma, cephalohematoma becomes most apparent in the first one to three days following birth rather than being immediately apparent. Some providers may request additional tests, including skull x-rays or computed tomography (CT) scans of the head if there is a concern for an underlying skull fracture or head ultrasound if there is a concern for intracranial hemorrhage. The newborn should be monitored closely for the neurologic deficit, as this could suggest that an intracranial bleed is present and requires further investigation.

Infants should be evaluated for bleeding diathesis, such as von Willebrand disease, which may have predisposed the infant to develop cephalohematoma.[2] Needle aspiration of the cephalohematoma is discouraged due to the risk of introducing infection and is only indicated if an infection is suspected. Escherichia coli is the primary pathogen associated with infected cephalohematoma.[2][1][11]

Treatment / Management

Treatment and management of cephalohematoma are primarily observational. The mass from a cephalohematoma takes weeks to resolve as the clotted blood is slowly absorbed. Over time, the bulge may feel harder as the collected blood calcifies. The blood then starts to be reabsorbed. Sometimes the center of the bulge begins to disappear before the edges do, giving a crater-like appearance. This is the expected course for the cephalohematoma during resolution.[12][13][14][15]

One should not attempt to aspirate or drain the cephalohematoma unless there is a concern for infection. Aspiration is often not effective because the blood has clotted. Also, entering the cephalohematoma with a needle increases the risk of infection and abscess formation. The best treatment is to leave the area alone and give the body time to reabsorb the collected fluid.

Usually, cephalohematomas do not present any problem to a newborn. The exception is an increased risk of neonatal jaundice in the first days after birth. Therefore, the newborn needs to be carefully assessed for a yellowish discoloration of the skin, sclera, or mucous membranes. Noninvasive measurements with a transcutaneous bilirubin meter can be used to screen the infant. A serum bilirubin level should be obtained if the newborn exhibits signs of jaundice.

Rarely, calcification or ossification may occur in cases that do not resolve.[16][1] A skull x-ray or CT scan of the head is indicated in patients whose cephalohematomas have not resorbed within 6 weeks of birth.[2] Rather than absorbed, an ossified cephalohematoma has hardened and has a clearly defined outer and inner layer of the bone surrounding the lesion.[1][3] The inner layer of the ossified cephalohematoma is composed of the outer and inner table of the infant's calvarium, while the outer table is composed of the infant's subpericranial bone derived from the elevated pericranium.[1] The contour of the inner layer of the ossified cephalohematoma can follow either the convex shape of the calvarium or become concave, encroaching upon the intracranial compartment.[1]

There is an ongoing debate regarding conservative management versus early surgical intervention for cephalohematoma, as there are no randomized controlled trials for reference. It has been suggested that early surgical intervention is not necessary if the cephalohematoma diameter is >50 mm unless other clinical indications are present.[17]

In patients with later-stage ossification or calcification, the advocates for surgery argue that outcomes are superior with intervention at an earlier age due to the infant's natural molding process, decreased risk of elevated intracranial pressure, and cosmetic advantage.[2] A rare surgical indication for ossified cephalohematoma is persistent cosmetic disfigurement.[2]

When indicated, ossified cephalohematoma can be treated safely surgically with craniotomy or craniectomy and cranioplasty, yielding good outcomes.[1][3] The surgical technique involves resection of the overlying newly formed bone, the soft tissue mass, as well as the underlying original bone.[1] Following removal, the underlying depressed region is often sectioned into multiple pieces and is remodeled as a bone graft. There are multiple techniques for cranioplasty, each with favorable outcomes and minimal if any, residual evidence in the following years.[3]

Differential Diagnosis

Caput Succedaneum

Caput succedaneum is scalp edema located above the epicranial aponeurosis and beneath the overlying skin. The swelling in caput succedaneum is poorly defined and crosses suture lines. In contrast to cephalohematoma, caput succedaneum is present at the time of birth and typically disappears in the following days.[2]

Subgaleal Hematoma

Subgaleal hematomas are located superficial to the periosteum and beneath the epicranial aponeurosis. Subgaleal hematoma may be associated with the rupture of emissary veins, becoming life-threatening, also presenting immediately after birth or a few hours later.

Prognosis

The majority of cases of cephalohematoma resorb within the first month of life in ~80% of cases.[1] Children typically do not have an associated neurologic deficit as the cephalohematoma is superficial to the calvarium and not in contact with the brain parenchyma.[1]

Complications

Rare complications associated with cephalohematoma include anemia, infection, jaundice, hypotension, intracranial hemorrhage, and underlying linear skull fractures (5-20% of cases).[2][18][19][18][2]

Pearls and Other Issues

Newborns with a cephalohematoma and no other problems are usually discharged home with their families. Parents need to observe the bulge on the newborn's head for any changes, including an increase in size during the first week following birth. Parents also need to monitor for any behavioral changes such as increased sleepiness, increased crying, change in the type of cry, refusal to eat, and other signs that the infant might be in pain or developing a new problem. Recovery from a cephalohematoma requires little action except for ongoing observation. While seeing a bulge on a newborn's head can be concerning, a cephalohematoma is rarely dangerous and typically resolves on its own with no lasting consequences in the majority of cases.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cephalohematoma is a clinical diagnosis and is usually a benign complication of delivery. However, prior to discharge, the nurse and obstetrician should educate the patient on the importance of monitoring the infant for the first week. The infant should be observed for any behavior change, feeding difficulties, emesis, and failure to thrive. The majority of infants have an uneventful recovery.[20] An interprofessional team approach will provide the best education to the patient's family as well as the outcome for the patient. [Level 5]