Continuing Education Activity

The inferior alveolar nerve block involves the injection of a local anesthetic solution near the area of the mandibular foramen and the entry of the nerve into the inferior alveolar canal. This anesthetic technique is widely used in routine dental practice as it facilitates multiple surgical procedures. This activity reviews the anatomy relevant to and indications for the inferior alveolar nerve block, describes various techniques that facilitate the administration of the anesthetic agent, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving outcomes for patients who undergo this procedure.

Objectives:

- Identify potential indications of the inferior alveolar nerve block.

- Apply knowledge of the relevant anatomy to facilitate the proper administration of the inferior alveolar nerve block.

- Differentiate between the conventional and alternative techniques for the inferior alveolar nerve block concerning procedural execution, indications, and predicted outcomes.

- Report the potential complications of the inferior alveolar nerve block.

Introduction

The inferior alveolar nerve block is the most popular anesthetic technique dentists use in regular practice. The inferior alveolar nerve block provides temporary anesthesia sufficient for a number of surgical procedures. The technique involves the insertion of the needle in the area surrounding the mandibular foramen to deposit local anesthetic solution near the entry of the nerve into the inferior alveolar canal.[1]

One essential anatomical structure in the insertion area is the pterygoid plexus, which is posterior and superior to the mandibular foramen. Technical failure of the inferior alveolar nerve block is mainly due to improper identification of anatomical landmarks and not because of a rare anatomical variation. The failure rate is reported to be around 15% to 20%.[2] The procedure is usually well tolerated, and severe complications are uncommon.

Anatomy and Physiology

Branches of the Mandibular Nerve

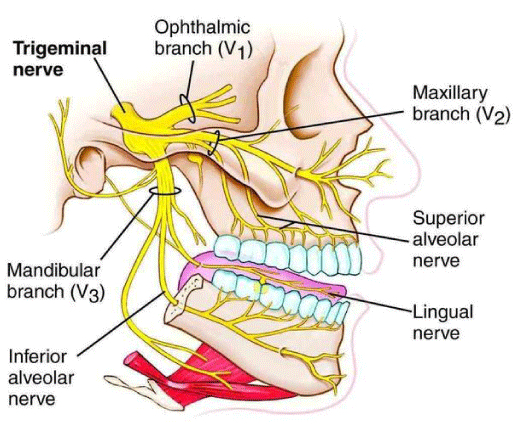

The mandibular nerve is the third division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V division V3). The mandibular nerve leaves the skull via the foramen ovale at the cranium base, dividing into anterior and posterior branches (Figure 1). The main trunk of the mandibular nerve gives off a branch that supplies the medial pterygoid muscle and a meningeal branch known as nervus spinosus. The anterior division of the mandibular nerve contains mainly motor fibers that supply the temporalis, lateral pterygoid, and masseter muscles. A sensory branch, the long buccal nerve, emerges from the anterior division. The posterior division is mainly sensory, giving off the auriculotemporal, lingual, and inferior alveolar nerves. Before entering the mandibular foramen, the inferior alveolar nerve gives a branch to the mylohyoid muscle; the nerve then enters into the inferior alveolar canal and terminates into 2 terminal branches, the incisive and mental nerves.[1]

Location of Mandibular Foramen

For an inferior alveolar nerve block to be effective, the local anesthetic solution must be deposited near the nerve before entering the mandibular foramen. Few studies have described that the deposition of local anesthetic molecules into the pterygomandibular space can produce the desired anesthesia.[3]

Literature suggests that the position of the mandibular foramen may vary. The mandibular foramen may not always be located midway within the anteroposterior dimension of the mandibular ramus. The foramen lies around 2.75 mm from the middle of the mandibular ramus in the posterior direction. Also, the distance between the mandibular foramen and coronoid notch is suggested to be 19 mm; it may be either level with or below the occlusal plane. The location of mandibular foramen in relation to the occlusal plane may also vary with age. The mandibular foramen is located below the occlusal plane level in adults, and in children, it is found below or at the level of the occlusal plane.[4]

Indications

The inferior alveolar nerve block provides temporary anesthesia to the following structures: the mandibular teeth in the ipsilateral quadrant, gingival tissue, and mucoperiosteum of the mandibular arch; it also blocks the sensory innervations of the lower lip. Many surgical procedures of the mandible can benefit from this block, such as tooth extraction, surgical reconstruction, root canal, periodontal treatment, and stabilization in traumatic and fracture cases.[5]

Contraindications

A known allergy to a particular local anesthetic agent can contraindicate an inferior alveolar nerve block, but often another agent can be applied in replacement. There is no absolute contraindication to the technique itself. Still, infection or acute inflammation at the injection site is known to decrease the efficacy of the anesthesia, and the procedure may be delayed until the acute phase of the disease has been resolved.[6] Special care may be needed to prevent post-anesthesia traumatic lesions in patients likely to bite their lips or tongue due to a prolonged anesthetic effect, such as children or patients with developmental delay.

Equipment

The most common anesthetic agent used for dental procedures is 2% lidocaine with 1:100 000 epinephrine. In patients where bleeding can be a problem, 1:50 000 epinephrine is recommended for hemostasis. Articaine is frequently utilized in 4% concentration and with vasoconstrictors because of its vasodilatory effect. This agent has been reported to have a more prolonged effect than 2% lidocaine when used for the inferior alveolar nerve block.[7] Employ a sterile, disposable long dental needle with a dental syringe to deliver the anesthesia. Topical anesthesia, such as 20% benzocaine, may also be applied to the mucosa before the injection to numb the area and reduce pain.

Personnel

The administration of the inferior alveolar nerve block is done as a sole operator; sometimes, an assistant may be required to retract the cheek.

Preparation

The operator must stand on the opposite side to where the injection will be administered. The patient is put in a semi-inclined position with the head stabilized on the chair and the mouth wide open to allow proper visualization of the anatomical landmarks and needle insertion. A topical anesthetic, such as 20% benzocaine, can be applied to the target area to reduce pain during injection.[1] This area must be dried with gauze to increase the penetration of the topical anesthesia solution into the mucosa.

Technique or Treatment

Conventional Technique

The conventional inferior alveolar nerve block technique is the most commonly used approach. Recognition of the following anatomical landmarks is imperative: the coronoid process, coronoid notch, anterior and posterior margin of the mandibular ramus, and the sigmoid notch. Other significant landmarks are the coronoid notch and the pterygomandibular raphe formed by the buccinator and superior constrictor muscles; the preferred location of needle entry is between these 2 structures. The syringe barrel is placed over the premolars opposite the side of the injection. The insertion point is an imaginary line starting at the deepest part of the pterygomandibular raphe and continuing to the coronoid notch. The exact location of the entry point is one-fourth the distance towards the raphe above the occlusal level of mandibular teeth. The needle is inserted after locating the target area until bony resistance is felt. The depth of penetration is between 19 and 25 mm. After that, the needle is withdrawn gently and slowly. When the needle can be inserted more than 25 mm, it may be posterior to the posterior border of the mandible. If the bone is touched prematurely, it suggests an anterior position of the needle.[8]

Modifications to the Conventional Technique

Various modifications or alternatives to the conventional inferior alveolar nerve block technique have been reported.

- Thangavelu et al. proposed the internal oblique ridge as the only pertinent anatomical landmark. This technique requires placing the thumb on the retromolar area; the tip of the thumb will indicate the internal oblique ridge. The insertion point will be 2 mm posterior to the internal oblique ridge and 6 to 8 mm above the midpoint of the thumb. The syringe is located over the opposite premolars, and the needle is moved along until it touches the bone. This technique has a success rate of 95%.[7]

- Boonsiriseth et al. employed a 30 mm long needle, and the insertion point was similar to the conventional inferior alveolar nerve block technique. However, the syringe barrel was located at the occlusal level of the ipsilateral teeth, whereas in the conventional method, it is located on the opposite side.[9]

- Suazo Galdames et al. advocated for the inferior alveolar nerve block via the retromolar triangle approach. This technique involves the deposition of the anesthesia at the retromolar triangle. It is based on the fact that the bone in this area is perforated by holes of different sizes, allowing for the passage of the buccal artery that anastomoses with the inferior alveolar vessels in the mandibular canal. Anesthesia administered in this area can reach the inferior alveolar nerve through communication between the mandibular canal and the retromolar triangle. This technique has a success rate of 72%. It can be particularly valuable in patients with blood disorders where the conventional inferior alveolar nerve block may be difficult.[8]

- Other available techniques mainly target the mandibular nerve branches rather than the inferior alveolar nerve. These include the Gow-Gate, Vazirani or Akinosi closed mouth, and the Fischer 3-stage techniques.[10]

Computer-Controlled Local Anesthetic Delivery (CCLAD)

This automatic device reduces the pain inflicted during the injection by slowly and continuously administering a small anesthetic solution. There are single-use, disposable, and lightweight hand-piece devices. These are generally utilized for the attached gingiva, hard palate, and periodontal ligament anesthesia. These devices can also provide more accurate anesthesia delivery when a deep tissue block, like an inferior alveolar nerve block, is needed.[7]

Complications

Complications associated with the inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) vary in severity. Mucosal tearing during the progression or withdrawal of the needle may cause pain and trismus.[11][12][13] Hematomas may develop due to the accidental nicking of the pterygoid venous plexus or following the intravascular injection of the anesthetic solution.

Facial paralysis is a rare but reported complication of the IANB. This paralysis may be immediate or delayed.

Immediate facial paralysis occurs soon after the injection and resolves within approximately three hours.[11] The paralysis lasts as long as the local anesthetic agent does; the time is usually longer for epinephrine-containing anesthesia.[14] The most common cause of immediate facial nerve paralysis is the direct anesthesia of a branch of the facial nerve, which generally occurs after administering the injection too posteriorly and injecting anesthesia in the parotid gland.[11] The parotid gland envelops the facial nerve; hence, an intraglandular injection may result in anesthesia of the nerve with resulting paralysis.[11] However, facial paralysis may also occur when the anesthesia is administered appropriately, but the facial nerve branches have aberrant anatomy in the retromandibular space.[11] Other suggested causes of immediate facial paralysis include direct trauma from the needle, development of a hematoma compressing the nerve, and air blast during surgery.[14]

Delayed facial nerve paralysis occurs within several hours to days after IANB, and the recovery time may range from 24 hours to several months.[11] The etiologies of this type of paralysis are varied and more complex.[14] In some cases, local trauma may trigger the reactivation of a latent herpes simplex or varicella zoster infection, resulting in the inflammation of the neural sheath. Other cases may be caused by axonal ischemia due to the delayed reflex spasm of the vasa nervorum of the nerve, possibly due to the mechanical action of the needle, the presence of anesthetic metabolites, or the infiltration of the anesthesia. It has been suggested that direct damage or ischemia of the facial nerve due to excessive stretching during prolonged dental treatment may contribute to delayed paralysis, as can the intraarterial anesthesia injection.

Paralysis of the lingual nerve, paresthesia, or dysesthesia has also been reported. Other infrequent complications include ptosis, extraocular muscle paralysis, skin necrosis over the chin, diplopia, and abducens nerve palsy.[15]

Clinical Significance

The inferior alveolar nerve block, when correctly performed, provides excellent anesthesia of the ipsilateral mandibular teeth, gingiva, mucoperiosteum, and lower lip for the duration necessary to perform routine dental procedures. Providers must select the most suitable technique in each case and know the anatomic landmarks and steps required. Even though many methods have been described, the most widely used technique is the conventional approach.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The inferior alveolar nerve block is considered a challenging injection. Therefore, the dentist, assistants, and other healthcare team members must possess a thorough knowledge of the relevant anatomy, necessary equipment, different anesthetic agents, and the technique itself to improve the outcome of any procedure.