Introduction

Emissary veins are valveless venous structures that connect the extracranial vessels of the scalp to the intracranial dural venous sinuses and diploic veins. The presence and distribution of the emissary veins vary from person to person, and during childhood, these venous structures are found more frequently and with larger foramina. The valveless nature of these vessels facilitates bidirectional blood flow, which allows for the equalization of intracranial pressures and selective cooling of the brain.[1]

During times of pathologically elevated intracranial pressure, the emissary veins may serve as ‘safety valves.’ Emissary veins may serve as essential sources of perioperative bleeding and thrombosis, as well as have the potential to provide a dangerous pathway for infection to reach deep intracranial structures.

Structure and Function

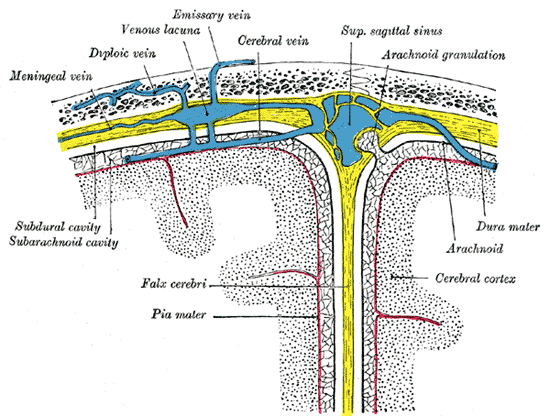

The layers of the scalp contain highly vascularized and complex structures. Emissary veins play a vital role in facilitating venous communication between the pterygoid venous plexus within the infratemporal fossa and the cavernous sinus within the middle cranial fossa. The pterygoid venous plexus is a rich venous network, directing blood flow to the maxillary vein and the retromandibular vein posteriorly and into the ophthalmic veins and the anterior facial vein anteriorly.[2]

Tributaries of the pterygoid venous plexus include the sphenopalatine vein, pterygoid vein, masseteric vein, middle meningeal vein, inferior ophthalmic vein, greater palatine vein, alveolar vein, buccal vein, and the deep temporal vein. Blood can flow from the pterygoid venous plexus into the cavernous sinus through the bridge created by emissary veins. Major tributaries of the cavernous sinus include the superficial middle cerebral vein, the sphenoparietal sinus, the superior ophthalmic vein, the inferior ophthalmic vein, and the middle meningeal vein. Emissary veins also drain into diploic veins, located between the internal and external layers of compact bone within the skull.[3]

The emissary veins also facilitate the cooling of the brain during periods of increased temperature. While in the upright position, warm blood rises and is allowed to leave the intracranial structures and enter the extracranial circulation via their emissary passages. Upon reaching the extracranial circulation, the blood cools by evaporation occurring on the surfaces of the head. Under normal physiologic conditions, blood typically flows through the emissary veins in an extracranial to intracranial direction. However, due to the valveless nature of these vessels, the direction of blood flow may be reversed to equalize elevated intracranial pressures resulting from traumatic brain injury, cerebral congestion, jugular vein obstruction, and similar pathologies.[4][5]

The specific emissary vessels derive their names from the anatomical foramina they traverse, such as the posterior condylar, mastoid, occipital, parietal, and ophthalmic emissary veins. The vessels connected by these emissary veins appear below.

- Posterior Condylar emissary vein: joins the internal vertebral plexus to the sigmoid, marginal, or occipital sinuses.

- Mastoid emissary vein: joins the posterior auricular or occipital veins to the transverse or sigmoid sinus.

- Occipital emissary vein: joins the occipital vein and the transverse sinus.

- Parietal emissary vein: joins branches of the superficial temporal vein of the scalp to the superior sagittal sinus.

- Ophthalmic emissary veins: join the vessels draining the orbital structures to the cavernous sinus.

Embryology

The emissary veins derive from the cerebral capillary venous plexus, which has three layers. The superficial layer of vessels drains the extracranial tissues, the middle layer forms the cerebral venous sinuses, and the deep layer forms the veins of the brain. The emissary veins persist as connections between the superficial and middle layers and may be visible as early as the third month of fetal development.[6]

When the embryo is no longer able to meet its respiratory, nutritional, and excretory needs, by simply spreading the nutritional fluids, it develops a system of vessels capable of distributing oxygen and nutrients to its tissues and transporting waste products. The venous system arises from the mesoderm.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Although there is no direct lymphatic drainage associated with the emissary veins, we will discuss the lymphatic drainage of the vascular structures that anastomose with emissary veins both superiorly and inferiorly; namely, the cavernous minus and the pterygoid venous plexus, respectively. The ultimate destination of blood that is received by the cavernous venous sinus is the internal jugular vein.

Lymphatic drainage of the internal jugular vein occurs via the deep cervical lymph nodes, also known as the internal jugular chain. Blood flow from the pterygoid venous plexus mainly flows into the maxillary vein and the retromandibular vein, formed by the joining of the maxillary vein with the superficial temporal vein. Superficial and deep parotid lymph nodes drain the maxillary vein and retromandibular vein as they course through the parotid gland.

Nerves

The emissary veins traverse through foramina in the skull associated with the passage of particular cranial nerves or through smaller foramina that do not transmit nerves. In addition to the previously mentioned emissary veins, some also consider the ophthalmic vein to be an emissary vein because it is a valveless vessel that connects extracranial and intracranial structures.[4]

The ophthalmic and condylar emissary veins exit the skull through the superior orbital fissure and the hypoglossal canal, respectively. Cranial nerves III, IV, V1, and VI courses through the superior orbital fissure, along with the ophthalmic emissary vein. The condylar emissary vein passes through the hypoglossal canal, an aperture that also transmits Cranial nerve XII (hypoglossal nerve). The mastoid, occipital, and parietal emissary veins course through foramina that are not associated with any specific nerves.[4]

Muscles

In the vein walls, there are three layers or tunics: an intima (is the name of the mucous membrane in the blood vessels), a tunica media (is the name of the muscle layer in the blood vessels), and adventitia. However, in the veins, this structural schematization is not constantly applicable since, alongside veins that show a wall of considerable complexity, other veins present an extreme constitutive simplicity and also because often the delimitation between the individual cassocks is not as evident as in the arteries.

The elements that make up the venous wall are the same as those of the arteries: the endothelium, collagen fibers, elastic fibers, and muscle cells, but there is, in the two types of vessels, a clear difference in the quantity and order of the individual materials composing the structure. The vein wall differs from that of the arteries mainly due to the lesser development of the elastic contingent and to the clear prevalence of the collagen material that forms the underlying texture. This composition gives the veins mechanical and functional characteristics that are different from those of the arteries and in harmony with the conditions of the circulation that occurs in the veins at lower pressure.

Physiologic Variants

There is about 2.6% of venous anomalies deriving from an aberrant embryological path. These can be asymptomatic (more often than not) or symptomatic (venous angiomas or vascular malformations). Veins with anatomy or path that deviates from normal physiology are called "Developmental venous anomalies (DVAs)." Probably, they result from a sudden arrest of their growth during the fetal period. They work fine, but they are potentially more prone to breakage, as they have a weaker structure. The incidence of stroke due to venous rupture of the DVA is about 0.22 on an annual basis. DVAs are associated with the presence of cavernous malformations.[7]

Surgical Considerations

Knowledge of the anatomy, position, and presence of emissary veins during surgical procedures can prevent potential complications associated with accidental lesioning of emissary veins, including air embolism, significant bleeding, and venous thrombosis.

Examples of two surgical procedures for which emissary veins should be considered and protected include surgery to repair craniosynostosis and middle ear surgery. Craniosynostosis is a congenital skull deformity that results in the premature fusion of the bones in an infant's skull. This condition requires surgical correction to prevent craniofacial deformity and delay in an infant's developmental abilities. Di Rocco et al. (2018) have revised a current surgical technique used in the repair of a specific type of craniosynostosis, trigonocephaly, intended to reduce the risk of damaging emissary veins during this surgery.[8]

During middle ear surgery, if emissary veins are lacerated, the rupture in these veins can lead to thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus.[9] An air embolism is another potential complication that may arise during surgeries in which there is the potential for lesioning of an emissary vein, as the ruptured blood vessel can allow air to escape the vein and lead to the obstruction of other veins or arteries to which the air travels. Careful detection of emissary veins during surgery is critical to avoid the potentially life-threatening consequences that may arise from lesioning of these vascular structures.

Clinical Significance

The loose areolar connective tissue of the scalp is often referred to as the "danger area of the scalp" due to the potential for the emissary veins which reside here to serve as conduits for the spread of infection. Due to the unique connection formed by emissary veins between the extracranial and intracranial spaces, infections that originate in more superficial regions of the head and neck can travel and spread to deeper intracranial structures through these veins. A post-mortem examination of one patient who developed cavernous sinus thrombosis and meningitis due to the spread of an infection originating from an infected hair follicle revealed the spread of the infection through the mastoid emissary vein.[10]

Aside from serving as a dangerous pathway for the spread of infections, abnormally enlarged emissary veins may have potential involvement in the development of pulsatile tinnitus. One such case involved a young woman diagnosed with pulsatile tinnitus who had a dilated posterior condylar emissary vein; the patient showed a reduction in her symptoms following ligation of the internal jugular vein.[11]

Other Issues

When can DVA be symptomatic? The etiologies related to clinical problems have flow-related, mechanical origins, and idiopathic origins. The mechanical causes can trace back to the presence of hydrocephalus or compression of a nerve pathway. The causes related to flow problems are related to disorders such as the presence of shunts: arteriovenous; increased or decreased. Symptomatic DVA problems can manifest themselves with headaches, neurological problems, coma.[7]