Introduction

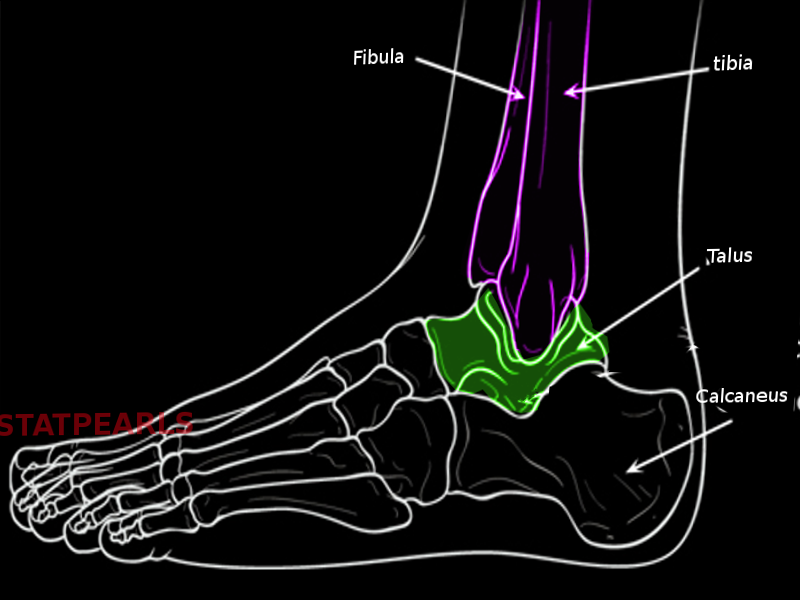

The talus is the second largest bone in the hindfoot region of the human body. Responsible for transmitting body weight and forces passing between the lower leg and the foot[1] the talus is a component of many multiple joints, including the talocrural (ankle), subtalar, and transverse tarsal joints.[2] While the talus does not have any direct muscular attachments and has a tenuous and limited blood supply, it serves as the site of attachment for many ligaments including the lateral ankle ligaments and medial deltoid ligament complex. Talus fractures comprise about 1% of all foot and ankle fractures. Additionally, nearly 70% of ankle injuries can cause varying degrees of chondral and osteochondral injuries to the talus.[3][4][5] The clinician must be aware of the occurrence of both isolated and associated talar injuries and their extent of clinical and potentially long-term implications.[6][7][8][9]

Structure and Function

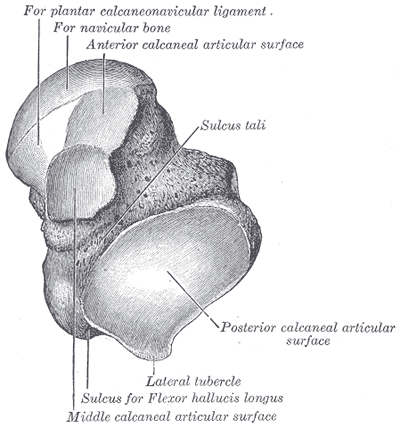

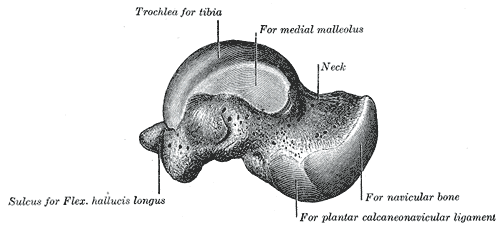

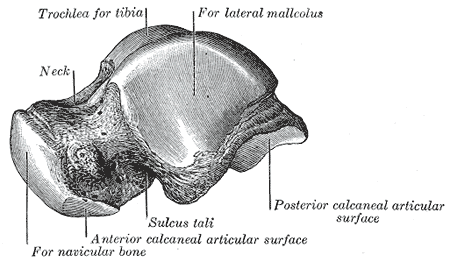

The talus is an irregular “saddle-shaped” bone composed of the head, neck, and body. Located on the anterior aspect of the talus, the head articulates anteriorly with the navicular to form the talonavicular (TN) joint, inferiorly with the calcaneus at the anterior facet to form the anterior talocalcaneal (TC) joint, and with both the navicular and calcaneus to form the talocalcaneonavicular (TCN) joint. The talar neck connects the head and the body, and the inferior aspect of the neck on the posteromedial aspect forms the narrow tarsal canal, which turns into the wider sinus tarsi on the anterolateral aspect of the talus. Comprising a majority of the talus, the body has three processes (medial, lateral, posterior), two facets (middle and posterior), two tubercles (medial and lateral), and one talar dome. On the medial aspect of the talar body, the medial process serves as a site for ligamentous attachment, and the middle facet articulates with the calcaneal sustentaculum tali. On the lateral aspect of the talar body, the large triangular-shaped lateral process articulates with the fibula superiorly and forms the posterior facet inferiorly, which articulates with the calcaneus to form the posterior TC joint. The posterior aspect of the talar body is made up of the posteromedial posterior process, which splits into the medial and lateral tubercle. The flexor hallicus longus tendon is between the medial and lateral tubercle. Located on the superior aspect of the talar body, the talar dome (also called the talar trochlea), articulates superiorly with the tibia and fibula to form the tibiotalar (talocrural) joint.[3]

The talus has a variable morphology of its articular facets used to articulate with the calcaneus in the subtalar joint (the anterior, middle, and posterior facets). Patients from different backgrounds may have different morphology; a Modified Boyan Classification of talus describes the variable morphology. Type A talus has three articular facets, which are entirely separated and further classified on the distance between the anterior and middle facet; type A1 has less than 2mm, type A2 has 2-5mm, and type A3 has over 5mm. Type B Talus has two articular facets, where type B1 has incomplete separation of the anterior and middle facets, type B2 has no separation of the anterior and middle facets (complete fusion), and type B3 has a fused middle and posterior facet, with a separate anterior facet. Type C talus has one articular facet, where the anterior, middle, and posterior facets are all fused as one continuous facet. Variations in talus morphology contribute to different biomechanics of the subtalar joint, and research has determined that Type A tali provide the most stability.[4]

Acting as a bridge between the leg and foot, the talus distributes body weight to the foot and contributes biomechanically to various movements of the foot and ankle through the subtalar, transverse tarsal (Chopart), and talocrural joints.[3][6]

- Subtalar Joint: A functional joint consisting of three anatomic components, the TCN joint, tarsal canal/sinus tarsi, and the TC joint, which all contribute to inversion and eversion of the foot. Additionally, the subtalar joint transmits body weight from the talus to the medial and lateral longitudinal arches of the foot, playing an essential role in the maintenance of proper foot alignment. The TCN has been described as a ball-and-socket joint (named the coxa pedis), in which the talar head functions as the “femoral head” and the calcaneus and navicular function as the “acetabulum.” The tarsal canal and sinus tarsi contain a complex “V-shaped” ligamentous structure, composed of the inferior extensor retinaculum, cervical ligament, interosseous TC ligament, and the anterior TC ligament, which provides stability during subtalar motion. The posterior TC joint consists of the biconcave posterior facet of the talus, and the biconvex posterior facet of the calcaneus, and is supported by the interosseous TC ligament (extending from the inferior talus to the superior calcaneus), and numerous other soft-tissue structures. (CITE Subtalar Joint Anatomy).

- Transverse Tarsal (Chopart) Joint: A functional joint consisting of the TN and calcaneocuboid (CC) joints, which facilitates movement between the hindfoot (talus and calcaneus) and midfoot (navicular and cuboid). The transverse tarsal joint functions closely with the subtalar joint and also contributes to inversion and eversion of the foot. (CITE Ankle Biomechanics).

- Tibiotalar (Talocrural) Joint: A syndesmotic hinge-joint composed by the distal tibia, distal fibula, and the talar dome, which facilitates dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the foot. The medial malleolus of the tibia and lateral malleolus of the fibula project inferiorly, creating a pocket for the talar dome to sit in, making the joint a hinge-joint.

The talus serves as a site of attachment for numerous ligaments that stabilize the medial and lateral ankle and foot. The deltoid complex ligament (DCL) and spring ligament are on the medial side. The DCL is composed of superficial and deep layers, with the superficial layer containing the superficial posterior tibiotalar ligament (SPTL), tibiocalcaneal ligament (TCL), tibiospring ligament (TSL), and tibionavicular ligament (TNL) in a posterior-to-anterior order, and the deep layer containing the posterior tibiotalar ligament (PTT), deep tibiocalcaneal ligament (dTCL), and anterior tibiotalar ligament (ATTL) in the same order. The DCL restricts anterior, posterior, and lateral translation of the talus, as well as talus abduction. Additionally, the superomedial ligament (SML) of the spring ligament attaches to the talus on the medial ankle via fatty tissue, which runs from the calcaneus to the navicular and provides support to the talar head through maintaining the longitudinal arch of the foot. The TSL of the DCL connects to the SML, and anatomists have proposed that the components of the DCL and the spring ligament are all part of one continuous medial ankle joint capsule, which provides support to the ankle and subtalar joint. On the lateral aspect of the ankle, the talus serves as an attachment site for the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL). The ATFL originates on the anteroinferior lateral malleolus and inserts anterior to the lateral process of the talus. The PTFL arises on the posteroinferior lateral malleolus and inserts anterior and superior to the lateral tubercle of the talar posterior process. While the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) does not have a direct attachment on the talus, it is worth noting that is the third lateral ankle ligament. The lateral ankle ligaments function to resist ankle inversion at the subtalar joint and commonly suffer injury in inversion ankle sprains.[5][10][11][12]

Embryology

The talus and calcaneus appear as cartilage precursors during the eighth week of gestation, and by the ninth embryonic week, the subtalar joint starts forming, with the posterior aspect developing faster than the anterior aspect. With the fusion of three ossification centers, by the tenth week of gestation, the anterior, posterior, and medial portions of the talus form. The first ossification center fuses to create the head and body of the talus, the second fuses to develop the posterior process of the talus, and the third fuses to form the lateral process of the talus, Around the eleventh week of gestation, marks the completion of the tarsal canal and sinus tarsi. By the 14th week, the joints in the area, as well as their surrounding joint capsule and ligamentous structures (like the inferior extensor retinaculum) fully form.[4][5][13]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The talus receives its blood supply from three main arteries, the posterior tibial artery, peroneal artery, and anterior tibial artery (transitioning as the dorsalis pedis artery). The posterior tibial artery runs inferiorly and splits into posterior tubercle branches, which form a vascular plexus that supplies the medial and lateral tubercles. The posterior tibial artery continues inferiorly then breaks into the tarsal canal artery, which runs through the tarsal canal. The deltoid branch of the tarsal canal artery supplies the medial third of the talus body, while the rest of the talar body receives supply directly by the tarsal canal artery. The dorsalis pedis artery runs inferiorly, and it gives off the lateral tarsal artery, which forms anastomoses with the peroneal artery, from which the tarsal sinus artery originates. The tarsal sinus artery forms an anastomosis with the tarsal canal artery, where the tarsal canal artery enters the sinus tarsi. The medial tarsal branches of the dorsalis pedis artery supply the superomedial half of the talar neck, while the inferior talar neck branches of the tarsal sinus artery or tarsal canal artery supply the inferolateral half of the talar neck.[3][14]

Nerves

The talus is innervated on the medial side by the posterior tibial nerve and saphenous nerve, while the deep peroneal nerve innervates the dorsal aspect of the talus. The dorsolateral aspect of the talus is innervated by the medial dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve, while the lateral side of the talus receives innervation from the intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve.[15][16]

Muscles

The talus does not serve as the site of any muscle attachment, which is significant because that means the talus does not have secondary sources of blood supply. Therefore, if there is vascular compromise to the talus through traumatic injuries such as in the setting of displaced fractures, there is a relatively high risk of developing post-traumatic, avascular necrosis (AVN).[3]

Physiologic Variants

Accessory Bones:

Os trigonum is a frequently encountered accessory bone (incidence 1 to 25%) that forms due to incomplete ossification at the posterior process secondary ossification center around the tenth week of gestation. The three types of os trigonum are type I (complete separation from the talus), type II (connected to the lateral tubercle through hyaline cartilage), and type III (Stieda process, which is when the lateral tubercle appears elongated as it projects posteriorly). An os trigonum can cause symptoms when there is forceful ankle plantarflexion or from repetitive plantarflexion, which causes trauma to the cartilage connecting the os trigonum to the talus.[3][17]

The os talotibiale is a poorly studied, very rare accessory bone (incidence 0.05%) that is present on the dorsal aspect of the talar dome, directly anterior to the talocrural joint. It is a potential cause of anterior ankle impingement syndrome. The os supratalare is a very rare accessory bone (incidence 0.02 to 0.04%) that occurs on the dorsal aspect of the talar head or neck. It can be seen as free-standing or connected to the talus via cartilage, and while it typically does not cause pain, it can cause dorsal hindfoot pain. The os tali accessorium is another poorly studied, very rare accessory bone (incidence 0.02%) that presents on the medial aspect of the talus, potentially in the deltoid ligament. The os talus secundarius is a very rare accessory bone (incidence is 0.01%) that forms due to incomplete ossification at the lateral process secondary ossification center. Located on the lateral aspect of the subtalar joint and anterior to the lateral malleolus, it typically connects to the lateral talus via cartilage, and it may cause lateral ankle pain due to edema within the os talus secundarius and surrounding soft-tissue edema.[13][18]

Tarsal Coalition:

The talus can be involved in two different types of tarsal coalition patterns. The two patterns include the talocalcaneal and talonavicular coalitions. In general, these coalitions restrict motion secondary to the osseous or osseo-fibrous connecting constituents. It can occur congenitally when corresponding tarsal bones fail to separate during mesenchymal segmentation, or they can be acquired through trauma, arthritis, surgery, or abnormal growth patterns. A talocalcaneal coalition can cause general hindfoot pain, or it may be asymptomatic in patients, but by reducing subtalar joint mobility, it may lead to adjacent joint degeneration or predispose to traumatic injuries or fractures.[19]

Surgical Considerations

When planning osteotomies or other surgical procedures to correct foot deformities like pes planus, the patient’s talar morphology should be evaluated using the modified Boyan Classification. Considering the patient’s talus morphology, a surgical plan which uses great care when working near the anterior/middle facets is necessary, so they are not damaged. Damage to the articular facets may induce osteoarthritis in patients.[4]

Arthroscopic surgery can be performed to treat patients with osteochondral defects on the talus, and when treating patients with hindfoot osteoarthritis, triple arthrodesis (fusion of the talocalcaneal, talonavicular, and calcaneocuboid joints) is a surgical option. When creating portals with arthroscopy, consideration of the location of the surrounding neurovascular structures at risk is warranted and a critical portion of the procedure. Four different portals are options with triple arthrodesis, including the lateral portal (dorsal to the calcaneocuboid line), dorsolateral portal (medial to extensor hallicus longus tendon), dorsomedial portal medial to tibialis anterior tendon), and medial portal (distal to insertion of the tibialis posterior), all of which have corresponding neurovascular structures at risk. Each portal was found to have a good safety margin, but careful technique should still be used to prevent iatrogenic injury when performing arthroscopy.[15][20]

Osteochondral lesions of the talus (OLTs) can form when patients sustain trauma to the ankle, and up to 70% of ankle injuries cause osteochondral or chondral damage. When treating OLTs surgically, the size of the OLT plays a significant role in how the surgeon is going the treat the injury. OLTs under 150 mm in size are repaired via bone marrow stimulation methods, while OLTs over 150 mm get replaced with osteochondral transplants. MRI is routinely used to diagnose and grade OLTs and to prepare for surgery. However, a significant discrepancy between OLT size on MRI and the size of the lesion while performing arthroscopy has been seen, with MRI commonly overestimating the size of OLTs. Therefore, it is essential to educate patients about the possibility of a repair or replacement is done based on the actual size of the OLT during surgery and to ensure that all the proper supplies are prepared pre-operatively, especially for lesions close to the 150 mm size.[9]

Clinical Significance

Avascular necrosis (AVN):

Fractures of the talus have a high risk of developing AVN due to its inherently tenuous and limited blood supply. Talar fractures make up one percent of all foot and ankle fractures, and the most common (around 50%) talar fractures occur in the talar neck since it is the weakest part of the talus. Talar neck fractures are classified using Hawkins classification system:

- Hawkins I

- Nondisplaced fracture of the talar neck

- AVN rate: 0% to 13%

- Hawkins II

- Talar neck fracture plus subtalar dislocation

- AVN rate: 20% to 50%

- Hawkins III

- Talar neck fracture plus subtalar and tibiotalar dislocations

- AVN rate: 20% to 100%

- Hawkins IV

- Talar neck fracture plus subtalar, tibiotalar, and talonavicular dislocations

- AVN rate: 70% to 100%

Talar body fractures make up 20% of all talar fractures, and if a fracture extends through an articulating surface on the talar body, sequelae of osteoarthritis can occur.[8]

Avulsion Fractures of the Talus:

Lateral ankle sprains are the most common athletic injury, constituting 15 to 20% of all athletic injuries, and 85% of all ankle sprains. Due to the attachment of the ATFL and PTFL on the talus, avulsion fractures of the talus may occur when those ligaments suffer injury in lateral ankle sprains. One percent of all ankle sprains cause avulsion fractures of the talus, so it’s important to consider them in the differential diagnosis when patients present with symptoms a lateral ankle sprain, especially if patients have marked swelling, bruising, or difficulty weight-bearing.[12][7]

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome:

Located on the ankle's medial aspect, the tarsal tunnel forms a bony floor consisting of the tibia, talus, and calcaneus, and a fibrous roof consisting of the fibrous flexor retinaculum. The posterior tibial nerve, artery, vein, and posterior tibialis, flexor hallicus longus, and flexor digitorum longus tendons are inside of the tarsal tunnel, and the posterior tibial nerve has the potential to become entrapped within the space, known as tarsal tunnel syndrome. Characterized by pain, paresthesia, loss of sensation over the medial foot and ankle, patients may also experience weakness and muscle atrophy in severe cases. Bony lesions on the talus, such as osteophytes or osteosarcoma, may cause the posterior tibial nerve to get compressed in the tarsal tunnel, leading to tarsal tunnel syndrome.[16]

Pes Planus:

Through the subtalar joint, the talus maintains the medial and lateral longitudinal arches. When there is an alteration of talus morphology of the articular facets, the biomechanics of the subtalar joint change, which can lead to pes planus. Three facets are involved in subtalar biomechanics, the anterior, middle, and posterior facets; patients with a separate anterior and middle articular facet have more subtalar stability than other facet configurations. In areas with a high prevalence of pes planus, morphology with fused anterior and middle facets was more common, which may draw a link between talus morphology and pes planus, as well as other conditions such as osteoarthritis of the subtalar joint.[4]