Continuing Education Activity

Retrograde urine flow from the bladder to the upper urinary tract is known as vesicoureteric reflux. This article illustrates the anatomy and pathophysiology of vesicoureteric reflux, its clinical presentation, and various diagnostic methods. This activity also reviews the evaluation and management of vesicoureteral reflux and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the anatomical structures in voiding cystourethrogram with vesicoureteric reflux.

- Describe the technique of voiding cystourethrogram in regards to vesicoureteric reflux.

- Outline the potential complications of vesicoureteric reflux.

- Summarize the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to improve patients' outcomes affected by vesicoureteric reflux.

Introduction

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is the retrograde urine flow from the urinary bladder to the upper urinary tract. It is often genetic. VUR can be asymptomatic or associated with severe nephropathy. Early diagnosis and timely treatment of VUR can salvage the kidneys. Voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) is the gold standard method of diagnosis. VCU findings decide VUR gradings. Clinical presentation and VUR grade determine the treatment plan.

Anatomy and Physiology

The ureter is a tubular structure, continuous to the renal pelvis proximally. It runs downwards and drains urine from the kidney into the urinary bladder. The ureteric orifices/openings are located just lateral to the bladder trigone. The distal-most part of the ureter is continuous as an oblique tunnel within the urinary bladder. It is known as the intramural/intravesical part. The orifice typically remains closed due to its obliquity. The ureteric peristalsis causes a rise in ureteric pressure, which opens the orifice momentarily to propel urine into the bladder.

After urine propulsion, the ureter loses its pressure. The intravesical pressure rises again and closes the intramural ureteral part. The approximate ratio of intramural tunnel length to the ureteral diameter is approximately 5 to 1.[1] A decrease in the ratio is one of the causes of urine vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Other causes of reflux include the ectopic ureteric opening, immature bladder discoordination, or bladder dysfunction.

For voiding cystourethrogram (VCU), water-soluble contrast is used to fill the urinary bladder. It allows visualization of the bladder under fluoroscopy (discussed later). Fluoroscopy is performed to monitor contrast reflux from the bladder into the ureter or upper urinary tract. Reflux can occur during, before, or after voiding.

Indications

A voiding cystourethrogram is the imaging of choice to diagnose vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). Recurrent UTI, first febrile urinary tract infection (UTI) with abnormal renal ultrasound (US) are indications of VUR. Other indications are prenatal/postnatal urinary tract dilatation, dysfunctional voiding, bladder outlet obstruction, neurogenic bladder, dysuria, hematuria, trauma. Voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) is also useful for postoperative evaluation of the urinary tract.

Contraindications

There is no absolute contraindication of performing the voiding cystourethrogram (VCU). Relative contraindications are pregnancy, allergy to the contrast media, and acute UTI. VCU exposes the fetus to the radiation and not advisable in pregnancy. Use allergy prophylaxis or alternate method in patients with a history of allergy to iodinated contrast. Perform VCU after treating acute UTI with antibiotics.

Equipment

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) requires a fluoroscopy machine. Radiologists view the real-time x-ray on a monitor of the fluoroscopy machine during the study. The attached recording devices can record a static image or sequence of images (video). Digital fluorography computers can process and store these recorded images.

The study uses water-soluble, iodinated contrast media. Iothalamate meglumine is the most used contrast currently.[2]

Personnel

Radiologists perform the voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) procedure. A radiology technologist and nurse help to catheterize the patient. A radiology technologist assists the study.

Preparation

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) requires patient participation for voiding (in toilet-trained children and adults). Explain the study in detail beforehand. The study can be distressing for children. Fear and anxiety may affect the quality and result of the study. The performing radiologist or assistant should counsel the patients or their parents. Distraction and reassurance are common non-pharmacological methods to destress the children. The anxious children often require sedation. Midazolam is a commonly used sedating drug for VCU.[3]

The patients prone to develop endocarditis (e.g., with prosthetic valve or septal defect, etc.) require antibiotic prophylaxis before the study.

Technique or Treatment

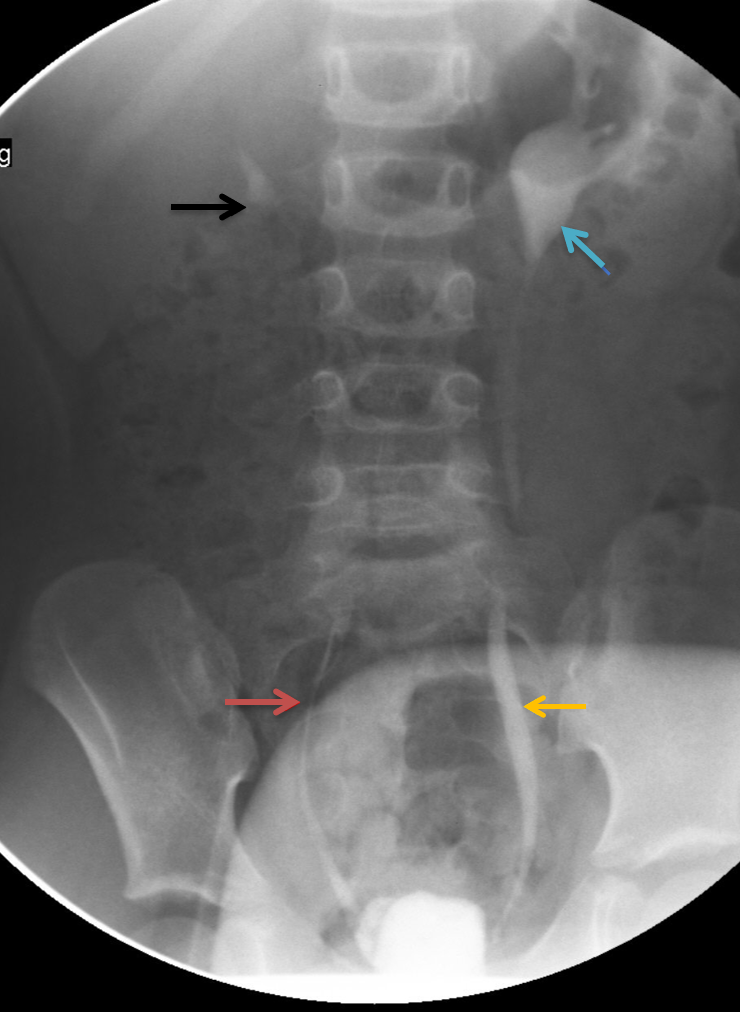

Review clinical history, preliminary studies, and imaging findings before the study. Obtain a single supine anteroposterior abdominal radiograph (scout image), including kidneys, ureter, and bladder. Fluoroscopic spot image is an alternative to the scout image. The x-ray is useful to evaluate the osseous abnormality, which may be associated with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) (spina bifida is often associated with neurogenic bladder and sometimes VUR). Document if any calculus is visible along the urinary tract. The scout image is useful to ensure that the abdomen is free of contrast. The contrast from a prior study (e.g., a contrast from a barium enema) may interfere with voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) findings.

The experienced nurse or radiology assistant catheterizes the patient with aseptic precautions. The anesthetic gel minimizes pain and discomfort. The size of the catheter is usually according to the patient's age.

5 French catheter- for premature or small infants, 8- French catheter- above one year of age, > 8 French catheter- for adolescents or adults.

A smaller caliber catheter is in patients with a history of urethral stricture or recent surgery. It is useful for its easy passage into the urethra. Avoid excessive length insertion in the bladder to prevent intravesical looping of the catheter. Secure the catheter to the perineum or thigh in females. Secure it along the dorsum of the penis or symphysis in males. Avoid circumferential tapping around the glans. Reposition the foreskin of the penis to avoid paraphimosis. Drain the bladder before the study.

Connect the bottle of water-soluble to the catheter via a tube. Place the bottle at a height to allow a gravity drip of contrast. The height of the contrast bottle should be at least 3 feet above the patient's table. However, the tubing's caliber (connected to this contrast bottle) limits the pressure, and height above 3 feet is relatively unimportant. Place the bottle at a lower height in patients with recent bladder surgery to maintain lower pressure filling.[2] After confirming the appropriate catheter position under fluoroscopy, contrast is allowed to drip into the bladder. Perform pulsed fluoroscopy to monitor contrast filling into the bladder. Use collimation to minimize radiation dosage to the patient. Fill the bladder retrogradely until voiding occurs (in non-toilet trained patients). Fill the bladder in toilet-trained children and adults until they want to micturate. The bladder is usually filled until twice its capacity. The formula for bladder capacity in ml: < 2 years: (weight in kilogram) x 7; 2 to 14 years: (age in years x 30) + 30; >14: years- 500.[4]

Stop the contrast filling if the patient feels pain or discomfort. Obtain fluoroscopic images of the bladder in anteroposterior, right anterior oblique, left anterior oblique, and lateral projections during early filling and when it is distended with contrast. Early filling images are useful to identify ureterocele. It is missed when the bladder is fully distended. Imaging of the full bladder is necessary to document its contour and shape. Document any wall irregularity, filing defects, or masses within the bladder. Oblique projections are useful to demonstrate grade I VUR (discussed later). A contrast-filled urinary bladder may obscure contrast reflux in the lower ureter in the supine position. Lateral imaging helps to identify urachal pathology.

Obtain anteroposterior fluoroscopic spot image in reflux occurs. Include renal fossa to evaluate the VUR grade. Record the volume of the bladder at the time of reflux. Acquire oblique images of the bladder during reflux to evaluate the insertion of the ureter into the bladder. Once the bladder is full to its maximum estimated capacity, ask the patient to void around the catheter. Adult males are more comfortable voiding while standing or when the table is tilted to 30-35 degrees. Acquire fluoroscopic spot images of the urethra when the patient starts to void.

Male patients are required to be slightly oblique during urethral imaging. It will ensure to avoid the superimposition of the pelvic bones on the urethra. Obtain frontal projection images for females. Perform lateral imaging in suspected urogenital sinus abnormality. Evaluate the images for urethral anatomy, extravasation, stricture, or fistula. Obtain renal fossa imaging immediately after voiding because VUR often occurs during or immediately after voiding.

Perform cyclical voiding to increases the possibility of VUR detection.[5] Fill the bladder with contrast and repeat the voiding cycle 2-3 times before removing the catheter. Cyclical VCU is routinely performed in children younger than one year of age because they void at a lower volume. It is also performed in patients with a high probability of having VUR (e.g., recurrent urinary tract infection, Hutch diverticulum, and pyelonephritis). Do not repeat a cycle if VUR occurs during the first filling. Cyclical voiding helps in urinary tract dilation. There is often dilution of refluxed contrast when it is mixed with unopacified urine in the dilated ureter. Diluted contrast is sometimes difficult to visualize under fluoroscopy, and grading is incorrect in such situations. Cyclical filling avoids dilution.[5]

A catheter masks some urethral pathology in males (e.g., posterior urethral valve). Therefore obtain urethral images after removing the catheter in male patients. Ensure to fill the bladder with contrast before catheter removal. Ask the patient to void after removing a catheter. Urethral imaging after catheter removal is not necessary for a female patient.

If the patient cannot void during the procedure, he/she can go to the bathroom if the bathroom is near the exam room. Obtain a supine image of the renal fossa immediately after voiding. Record the time between the image and voiding. Obtain post-void images to evaluate post-void residue. Include renal fossa in the post-void image that is necessary to evaluate reflux occurring immediately after voiding.

The international grading system of VUR:

- Grade 1: Reflux only into the non-dilated ureter.

- Grade 2: Reflux into the ureter and the renal pelvis without dilatation.

- Grade 3: Reflux with mildly dilated ureter and pyelocalyceal system.

- Grade 4: Reflux with the tortuous and moderately dilated ureter with blunting of renal fornices. The papillary impression is preserved.

- Grade 5: Reflux with the tortuous and severely dilated ureter, dilatation of pyelocalyces with loss of fornices, and papillary impression.

Grading of VUR is not possible if urinary tract obstruction coexists (e.g., pelviureteric obstruction). Dilatation and tortuosity are not necessarily due to VUR alone. It is often due to obstruction and may overestimate VUR grade.[6] Obtain delayed imaging after a few minutes of voiding in suspected urinary tract obstruction.[5]

Management of a child with vesicoureteral reflux disease and older than one year of age is ubiquitous. Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered for the child with bladder-bowel dysfunction and VUR. In the presence of BBD, the risk of urinary tract infection increases. The following recommendations should be considered in managing an older than a one-year-old child with a UTI and VUR: 1. ultrasonography every year to monitor renal growth and exclude any parenchymal scarring, 2. Voiding cystography, either with a radionuclide cystogram or low-dose fluoroscopy, every one to two years.[7]

Complications

The complications of voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) include an allergy to the contrast media. Use allergy prophylaxis if the prior episode of allergy to iodinated contrast exists, or consider other imaging studies.

Radiation exposure is another complication of the study. Newer advances in digital imaging are useful to reduce radiation. The average fluoroscopy dose is around 0.2 millisieverts (mSv). A study showed that the average dose from fluoroscopy during standing VCU in women was around 1.1 mSv.[8]

Clinical Significance

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is frequently associated with renal damage. If left untreated, it often results in renal scarring, renal hypertension, or chronic end-stage kidney disease.[9] Suspect VUR in children with UTI, because 30-40 % of infants presenting with UTI is associated with VUR.[10]

Renal scarring in VUR occurs by two main mechanisms: 1) Infected urine refluxing to the kidney creating inflammatory reactions. The inflammatory reaction often results in fibrosis, which leads to cortical scarring. It is more prevalent with VUR grade III-V. Around 50% of patients of acute pyelonephritis develop renal scarring.[11] 2) Sterile urine causes urinary back pressure on the renal pelvis and renal tubules. It is known as the "water hammer effect." Severe intrarenal reflux often results in the destruction of the tubules, parenchymal atrophy, and scarring.[12][13]

Ultrasound is the primary test for renal cortical abnormality detection. Nuclear renal scanning with DMSA is a more reliable test that evaluates renal scarring. Voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) is the radiographic test to diagnose VUR. Early testing in febrile UTI gives accurate results without significant health risk.[11][14] Direct radionuclide cystography (DRNC) is an alternative for the diagnosis of VUR. Perform DRNC when detailed anatomical evaluation of the urinary tract is not required. The radiation burden of DRNC is quite similar to VCU when performing VCU with modern dose reduction techniques.[15] Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is another modality for diagnosing VUR. CEUS is also useful in diagnosing urethral pathology. The main advantage of CEUS is that it is free of radiation risk.[16]

Management

Medical Management

Management of VUR has evolved based on different studies and their meta-analysis. The medical treatment depends on the presence or absence of febrile UTI, age & sex of the patient, presence of bladder or bowel dysfunction, and grade of VUR. Spontaneous resolution of VUR can occur before five years of age. Younger age and lower VUR grade (I-III) are favorable criteria for spontaneous resolution. They typically do not require surgical intervention if uncomplicated.[10][17]

Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) helps to prevent UTI and associated renal damage. VUR with febrile UTI is associated with high morbidity in infants. Therefore use CAP for them regardless of VUR grade. CAP is recommended for high-grade VUR (III-V) regardless of UTI. Nitrofurantoin, cephalosporins, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole are drugs of choice. There are discrepancies for CAP use in VUR grade I-II without febrile UTI. Some studies recommend CAP for every patient with VUR.[18]

Some studies discourage CAP because it has a limited effect on preventing renal damage, increasing the risk of antibiotic resistance. Few studies suggest to continue CAP for at least a year and then perform VCU annually. UTI risk is high in female and circumcised males. Perform a renal scan to identify renal cortical abnormality before considering CAP discontinuation. Consider surgery in recurrent UTI or renal damage despite continue CAP.

Surgical Management

Surgery is the treatment of choice in recurrent UTI despite CAP, high-grade reflux, low probability of spontaneous resolution, and evidence of renal damage.[19][20]

Endoscopic Treatment: It is an alternative to open surgery. Perform endoscopic surgery in those who require long term CAP (in VUR grade III-V) to avoid antibiotic resistance. A surgeon approaches the ureter via cystoscopy and injects a bulking agent into the submucosal, intramural tunnel of the ureter. It elevates the ureteric orifice. Thus downgrades or resolves the VUR.[20] There are promising results of endoscopy in lower grade VUR, although not as good as open surgery.

Open Surgery: Open surgery is the gold standard procedure and superior to other management. Surgery reimplants the ureter. The surgeon creates a longer ureteral segment that passes between bladder mucosa and muscularis propria. The replanted segment remains compressed with increased bladder pressure and prevents reflux.[19]

Minimally Invasive Procedure: Robot-assisted laparoscopic ureteral reimplantation (RALUR) is a newer technique. Its benefits are minimal invasion, decreased postoperative pain, and shorter hospital stay than conventional open surgery. Its results are as good as conventional surgery. The disadvantage is its high cost and requirement of skilled professionals.[19]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCU) is the gold standard procedure for diagnosing vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). It needs interprofessional communication between urologists/surgeons, and radiologists to conduct an appropriate study for an individual patient. VCU demands coordination among nurses, pharmacists, radiology technologists, and radiologists for appropriate contrast administration. The radiologist or the technologist explains the procedure to the patient beforehand. They answer all the related questions. Counseling and explaining the procedure reduces pain and apprehension in children.[21] [Level 1] Child life support should be involved to calm the anxious child.

It is a combined responsibility of all involved personnel to lower the radiation dose. Maintain a low dose per the “as low as reasonably achievable” (ALARA) principle. There are steps to lower the radiation dose during fluoroscopy.[22] Ten steps are provided by the image gently.