Continuing Education Activity

Lasers for tattoo removal were first used in the late 1960s, but they did not emerge as a primary treatment until the 1980s when the concept of selective photothermolysis allowed more specific targeting of tattoo pigment. Greater knowledge and utilization of optimal pulse duration and cooling times have led to further advancements of this technology. This activity reviews the principles of laser removal of tattoos and describes which lasers are useful for specific chromophores. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of individuals undergoing laser removal of tattoos.

Objectives:

- Describe the principles of laser destruction of tattoo chromophores.

- Explain which lasers are used to for different tattoo chromophores.

- Review when laser therapy of exogenous skin pigmentation should be avoided.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to enhance outcomes for individuals undergoing laser tattoo removal.

Introduction

Laser tattoo removal was first used in the late 1960s following the creation of the first laser, but removal often led to suboptimal results due to significant surrounding tissue destruction and scarring. It was not until the description of the theory of selective photothermolysis in the 1980s that exogenous tattoo pigment could be selectively targeted as a chromophore at specific wavelengths. According to this theory, the target chromophore must be heated quickly before it can cool. For optimal destruction, the pulse durations need to be shorter than the thermal relaxation time of the tattoo particle or the time that is required for the target to lose 50% of its heat. Due to the small size of the tattoo particles, rapid pulses of high heat at very short pulse durations in the nanosecond to picosecond range are required to prevent cooling of the particles. The thermal relaxation time of tattoo particles is thought to be less than ten nanoseconds. Lasers with Q-switched technology are capable of producing light pulses of short duration but with a peak power that is much higher than is achievable with continuous wave output. More recently, lasers of even shorter pulse duration have been developed, potentially offering better targeting of chromophores with less damage to surrounding tissue.[1][2][3][4][5]

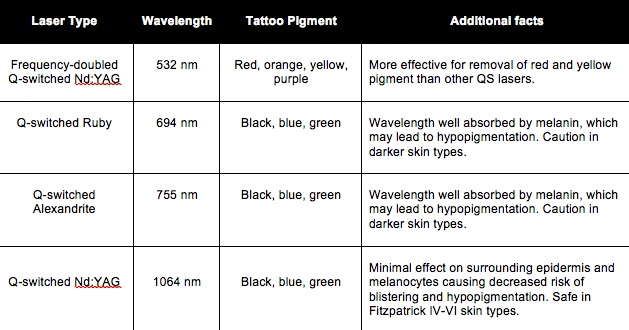

Laser Devices: The type of laser and wavelength chosen for removal largely depends on the patient’s tattoo color and skin type. Q-switched (QS) lasers such as the QS Ruby, QS Nd: YAG, and QS Alexandrite until recently were the most effective devices for tattoo removal. However, picosecond lasers have quickly become the mainstay of treatment due to their superior efficacy and decreased treatment durations. Now there are picosecond 532-nm, 694-nm, 755-nm, and 1064-nm devices available to target a wide array of tattoo pigments. Patients with Fitzpatrick IV-VI (darker) skin types should be treated cautiously due to increased risk for hypopigmentation following treatment. Lasers that penetrate deeper into the dermis, such as the Nd: YAG 1064-nm laser, are associated with a decreased risk of epidermal damage and hypopigmentation in this patient population.

Some chromophores for various laser wavelengths include:

- 532 nm - red, orange, yellow, brown

- 694 nm - black, blue, green

- 755 nm - black, blue, green

- 1064 nm - black, blue

Colors that respond best to laser removal are black, brown, dark blue, and green, while the most difficult colors to remove are red, orange, yellow, and light blue.

Epidemiology

Over the years, tattoos have become increasingly popular. According to a 2016 Harris Poll, 3 in 10 adults in the United States have at least one tattoo, compared to 2 in 10 adults in 2012. These tattoos have also become more elaborate, including a multitude of colors and dyes. As a general rule, the more advanced and colorful the tattoo, the more difficult will be its removal. Amateur tattoos tend to be located more superficially in the papillary dermis and easier to remove with a laser, whereas professional tattoos are located in the deep reticular dermis.

Pathophysiology

Q-switched (QS) lasers work by delivering high-powered pulses in very short pulse durations which results in the fragmentation of the tattoo particles. The high-powered pulses form acoustic waves, which are thought to be the main mechanism of tattoo particle destruction. Recently, picosecond lasers have become the mainstay of tattoo removal due to their shorter pulse durations. The picosecond pulse duration is considerably less than the thermal relaxation time of the tattoo pigment particles (< 10 nanoseconds), leading to rapid heating of the chromophore with minimal surrounding thermal damage. Furthermore, an inflammatory response is ignited in the weeks following treatment leading to macrophage phagocytosis of residual extracellular tattoo pigment.[6][7][8][9]

History and Physical

A thorough history is important to elicit information regarding prior scarring and wound healing, recent isotretinoin use, history of gold salt ingestion for rheumatoid arthritis (can result in blue-grey skin discoloration, or chrysiasis in laser treatment areas), or history of infectious disease. It is also important to inquire about “double tattoos” which can lead to a greater risk of scarring with laser removal.

Evaluation

Patients should be counseled that tattoo removal takes anywhere from 4 to 15 treatments depending on the age, color, quality, and mechanism of tattoo placement. It is also important to discuss the importance of sun avoidance pre- and post-treatment due to the risk of hypo- and hyperpigmentation. Photographs and consent should be taken at baseline and prior to every treatment. The risks of the procedure should be discussed such as hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, blistering, scarring, paradoxical darkening, and unpredictable treatment response.

Treatment / Management

The patient’s skin should be prepped with alcohol or chlorhexidine prior to the procedure. Due to the risk of flammability, alcohol should be completely dry prior to beginning treatment. The treatment area should be anesthetized with either topical or local anesthesia. Due to the unpredictable treatment response, a test area can be performed prior to treatment of the entire area. The intraoperative endpoint is immediate ash-white color caused by steam and gas bubbles. This is due to rapid heating of the particles, which typically resolves within 30 minutes following the procedure. The lowest possible fluence should be used to achieve this endpoint, minimizing surrounding epidermal damage. Picosecond lasers typically require lower fluences due to the shorter pulse duration.

Occasionally, paradoxical darkening of various tattoo pigments, specifically white, tan, red, or pink, can occur due to the oxidation of ferric oxide to ferrous oxide contained within the tattoo pigment. Pinpoint bleeding also may be observed and may indicate that the settings are too high.

Additionally, the R20 method can be a successful treatment option where four exposures to the laser are performed at 20-minute intervals. Also, a combination of lasers can be used out for optimal removal, including ablative lasers which may help improve paradoxical darkening as well as allergic tattoo reactions. For paradoxical darkening that is highly resistant to further laser surgery, surgical removal of the tattoo may be necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

- Skin discolouration that may be permanent

- Suboptimal aesthetic result

Pearls and Other Issues

Traumatic tattoos caused by explosions, such as with fireworks or gunpowder, can result in combustible material being embedded in the skin. Great care should be exercised in these circumstances, since the application of the laser can ignite these particles and result in small explosions, endangering the patient and caregiver, and resulting in disfiguring scarring.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Removal of tattoos is performed by many healthcare workers including primary care providers, nurse practitioners, cosmetic and plastic surgeons, and dermatologists. However, all healthcare workers should be aware of the potential complications of lasers and inform the patient prior to the procedure. Laser safety is mandatory to protect both the staff and the patient. Patients need to be told that not all tattoos can be removed with laser and the potential to cause more harm than good is a possibility.[10][11]