Continuing Education Activity

Prolactin-secreting tumors of the pituitary gland, also known as prolactinomas, are the most common secretory tumors of the pituitary gland, accounting for up to 40 percent of pituitary adenomas. Prolactinomas can lead to a wide variety of symptoms, either due to mass effect or hypersecretion of prolactin. This activity illustrates the evaluation, treatment, and complications of prolactinomas and the importance of an interprofessional team approach to its management.

Objectives:

- Identify the common presentations of prolactinomas.

- Outline the evaluation of prolactinomas.

- Review the management of prolactinomas.

- Explain the role of collaboration among interprofessional team members to improve care coordination and minimize oversight, leading to earlier diagnosis and treatment and better outcomes for patients with prolactinomas.

Introduction

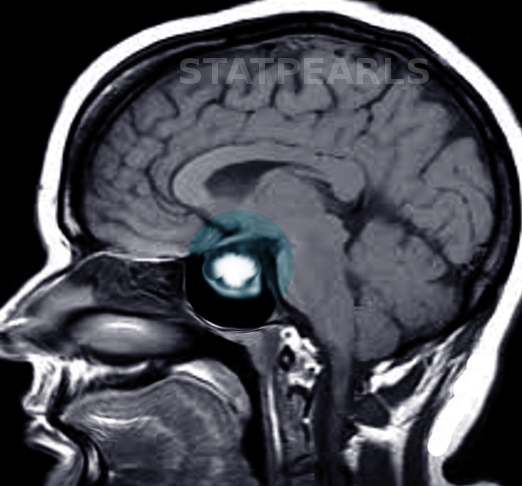

Prolactin-secreting tumors of the pituitary gland are called prolactinomas. It is the most common secretory tumor of the pituitary gland accounting for up to 40% of total pituitary adenomas. Prolactinomas cause a wide variety of symptoms, either due to mass effect of the tumor or due to hypersecretion of prolactin. Based on the size of the tumors, prolactinomas can be classified as micro prolactinoma (smaller than 10 mm), macroprolactinoma (larger than 10 mm), or giant prolactinoma (larger than 4 cm). Hyperprolactinemia is not always due to prolactinoma, and other causes like pregnancy, drugs, hypothyroidism, and pituitary stalk effect due to other pituitary tumors should be considered in the differential. [1][2]

Etiology

The exact cause of prolactinoma is poorly understood. Prolactinomas arise from monoclonal expansion of pituitary lactotrophs that have undergone somatic mutation. Pituitary tumor transforming gene (PTTG) overexpression and mutation of a receptor of fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4) have been found in pituitary adenoma, mainly prolactinoma. Most prolactinomas are sporadic in origin but can also occur as part of familial syndromes. Familial isolated prolactinoma and other pituitary adenomas have been described. It can be a part of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1); up to 15 to 60% of patients with MEN1 can have a pituitary adenoma, and the majority of them are prolactinomas.[3][4]

Epidemiology

Prolactinomas account for up to 40% of all clinically recognized pituitary adenomas. The mean prevalence of prolactinoma is estimated to be approximately 10 per 100,000 in men and 30 per 100,000 in women, with a peak prevalence in women aged 25 to 34 years. Among patients with prolactinomas, as many as 60% of the males present with macroprolactinomas, while 90% of the females present with microprolactinomas.

Pathophysiology

Prolactinomas arise from monoclonal expansion of pituitary lactotrophs and are mostly benign, often sharply demarcated without evidence of invasion. A few prolactinomas could behave aggressively with the invasion of surrounding local structures, and they generally have higher mitotic activity and are more cellular and pleomorphic. Distance extracranial involvement is required to be called a malignant prolactinoma. Lateral parts of the anterior pituitary are the most common sites involved with prolactinoma.[5]

Rarely mixed tumors that secrete growth hormone and prolactin, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and prolactin or thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and prolactin can also be seen, which is recognized with immunohistochemistry.

Microadenomas (smaller than 1 cm) usually are confined to sella turcica and do not cause any compressive symptoms, but macroadenomas (greater than 1 cm) can expand to an adjacent structure like optic chiasm, cavernous sinuses and causes various compressive symptoms like visual field defects, cranial nerve palsy, and headaches. Symptoms of microadenoma are mainly due to elevated levels of prolactin.

Prolactin levels are usually directly proportionate to the size of the tumor, ranging from below 200 ng/ml with less than 1 cm, 200 ng/ml to 1000 ng/ml with 1 cm to 2 cm, and more than 1000 ng/ml with tumor sized more than 2 cm in diameter. If prolactin level does not match with tumor size, then it can be either due to not well-differentiated prolactinoma or the presence of a large cystic component in the tumor.

Hypothalamus has a predominant inhibitory influence on prolactin secretion via dopamine, and any factor which disrupts this mechanism causes hyperprolactinemia. It is important to consider the various causes of hyperprolactinemia, as increased prolactin secretion is noted in many physiological and pathological states other than prolactinomas.

History and Physical

Prolactinomas clinically present because of the mass effect of the tumor or because of hyperprolactinemia. Microprolactinomas (less than 1 cm) can present with symptoms of hyperprolactinemia or are detected incidentally on neuroimaging done for other reasons. Macroprolactinomas, on the other hand, present with mass effects on the surrounding structures.

Signs and Symptoms Due to Mass Effect

- Headaches

- Vision changes-visual field deficits, blurred vision, decreased visual acuity

- Cranial nerve palsies-especially with invasive tumors or with pituitary apoplexy

- Seizures, hydrocephalus, and unilateral exophthalmos are rare presentations

- Pituitary apoplexy is a medical emergency because of spontaneous hemorrhage into the pituitary tumor and presents with severe headaches, vision changes, and panhypopituitarism.

Signs and Symptoms Due to Hyperprolactinemia

Males

- Decreased libido

- Impotence

- Erectile dysfunction

- Oilgozoospermia (due to secondary hypogonadism)

Females

- Oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea

- Infertility, loss of libido

- Galactorrhea

Children and Adolescents

- Growth arrest

- Pubertal delay

- Primary amenorrhea

Other features like osteopenia, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and emotional instability can be seen in both sexes. About 10% of prolactinomas can be co-secreting growth hormone, so gigantism/acromegaly can be seen in those patients.

Evaluation

An extensive history and physical examination are needed to exclude other causes of hyperprolactinemia and to document any visual field deficits, galactorrhea, growth changes, hypopituitarism, menstrual irregularities, impotence, infertility. Formal visual field testing by an ophthalmologist should be done, especially for macroadenomas. [6][7][8] The following differential diagnosis should be considered during evaluation:

Physiological Causes:

- Pregnancy

- Nipple stimulation in lactating women

- Stress

Pathological Causes:

- Craniopharyngiomas, meningioma, dysgerminoma

- Non-secreting pituitary adenoma

- Sarcoidosis; Histiocytosis X

- Cranial irradiation

- Prolactinoma

- Acromegaly/Cushing disease

- Empty Sella syndrome

- Lymphocytic hypophysitis

- Drugs (Dopamine antagonists)

- Antipsychotics

- Tricyclic antidepressants; SSRI

- Antiemetic: Metoclopramide, domperidone, prochlorperazine

- Antihypertensive: Verapamil, alpha-methyldopa

- Opioid analgesics: Morphine, methadone,

- Hypothyroidism

- Idiopathic hyperprolactinemia

Treatment / Management

Laboratory

The test begins with serum prolactin level. If the prolactin level is high, a comprehensive metabolic panel, TSH, and a pregnancy test (for women of childbearing age) should be obtained. Assessment of other pituitary hormones, including cortisol, ACTH, IGF-1, LH, FSH, and testosterone/estradiol, should be done based on age and gender to exclude any hypopituitarism or other co-secreting tumors.[9][10][11]

Patients can have very high prolactin levels; however, when measured, they can be reported as falsely low due to a phenomenon called the “Hook effect.” When there is a suspicion, serial dilution of the serum sample and re-measuring the prolactin levels will be helpful.

Another condition where measured prolactin can be high, although true prolactin level is low, is when patients have higher molecular weight prolactin called macroprolactin. Macroprolactin levels should be obtained in asymptomatic hyperprolactinemia. The laboratory can pretreat the serum with polyethylene glycol to precipitate the macroprolactin before the immunoassay for prolactin.

Imaging

CT scan may demonstrate the mass, but MRI with gadolinium is the preferred imaging modality for evaluation of hyperprolactinemia as it best describes the anatomy of the hypothalamic-pituitary area. All patients with tumors adjacent to or compressing to optic chiasm should be referred for formal visual field testing.

Treatment/Management

Macroprolactinomas incidentally discovered without symptoms can be observed with periodic monitoring of the labs and imaging.[12][13]

Macroprolactinoma or symptomatic microadenoma should be treated with dopamine agonist therapy. The goals of treatment would be tumor shrinkage, restoration of visual fields if any defect, reversal of galactorrhea, and restoration of fertility or abnormal sexual function. Cabergoline is preferred due to a higher frequency in normalizing the prolactin level and tumor shrinkage. Amenorrhea caused by macroprolactinoma can be treated with oral contraceptives if fertility is not desired without dopamine agonists.

Most prolactinomas are managed with medical therapy only with surgery and radiotherapy reserved for refractory cases.

Medical Therapy

Unlike other pituitary tumors, the preferred treatment for prolactinomas is medical therapy. Oral contraceptives alone can be given if the only symptoms are amenorrhea and or osteoporosis. Specific treatment for prolactinomas is one of the dopamine agonists.

Cabergoline and bromocriptine are two commonly used dopamine agonists. Pergolide is withdrawn from the market due to concerns about valvular heart disease, and quinagolide is not available in the United States. Dopamine agonists suppress the synthesis and release of prolactin and lactotroph cellular proliferation, causing shrinkage of the tumor. They can cause nausea and dizziness.

Bromocriptine is preferred during pregnancy if needed due to more available data than cabergoline. It is also cheaper but has more side effects than cabergoline, like nausea, vomiting, nasal stuffiness, and postural hypotension. It is started at 1.25 mg at bedtime or after dinner daily for one week, then increased to 1.25 mg 2 times a day (after breakfast and dinner). The dose should be increased every 4 weeks if the prolactin level is not normalized up to a maximum dose of 5 mg two times a day. If bromocriptine is unsuccessful, cabergoline should be started.

Treatment with dopamine agonist should be tapered and stopped if prolactin level is normal and the tumor is not visible in MRI after at least two years of treatment.

Estrogen replacement is an option for a woman with inadequate response to treatment and not desiring fertility. For a man with inadequate treatment response, testosterone therapy (if no fertility is desired) or human chorionic gonadotropin (if fertility is desired) should be started.

Surgery

Transsphenoidal surgery is the preferred surgical option if surgery is indicated for the following reasons:

- Unsuccessful medical therapy to lower prolactin level and decrease tumor size after several months of maximum dose.

- A woman with large prolactinoma (more than 3 cm) wishes to become pregnant as it can get larger during pregnancy.

- Radiation therapy should be considered for residual tumors after surgery and resistance to cabergoline therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

- Pregnancy

- Hypothyroidism

- Renal failure

- Breast stimulation

- Pituitary tumors

Complications

- Mass effect leading to visual deficits, cranial nerve palsies, or pituitary apoplexy

- Infertility

- Osteoporosis

- Complications related to surgery may include vision loss, CSF leak, permanent hypopituitarism

- Seizures

Consultations

- Neurosurgeon

- Radiation oncologist

- Endocrinologist

Pearls and Other Issues

Usually, in pregnancy, there is hyperplasia of pituitary lactotrophs, and prolactin levels increase. Prolactinomas increase in size during pregnancy, and in patients with known macroadenomas, one can consider surgery before pregnancy, or those on medical therapy should be monitored carefully with periodic visual field testing. Bromocriptine has the largest safety database in pregnancy and is the preferred drug during pregnancy.

Pituitary apoplexy is an endocrine emergency when there is spontaneous hemorrhage into the pituitary adenoma/prolactinoma and patients present with sudden onset headaches and vision changes. Any patient with known prolactinoma/pituitary adenoma presenting with the above symptoms would need an urgent MRI and neurosurgical/endocrine evaluation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Once a prolactinoma has been diagnosed, patient education is key to preventing high morbidity. All patients must be closely followed, and patients must be educated about the symptoms of prolactinoma and when to seek help. If the decision is made to taper or withdraw medical therapy, the patient must undergo imaging studies periodically to monitor for recurrence of growth. The pharmacist should educate the patient on drugs used to treat prolactinomas and their adverse effects. Finally, the oncology nurse should educate the patient on the possibility of radiation therapy for large lesions and the possibility of hypopituitarism.[14][15] {Level 5]

Outcomes

The majority of patients with microprolactinomas have an excellent prognosis. These patients can be managed medically for extended periods. Macroprolactinomas, on the other hand, can grow over time and require more aggressive treatment. The growth rate of macroprolactinomas is unpredictable, and the patient must be closely followed up. The decision to taper medical therapy requires sound judgment because the tumor can grow in size without treatment. [16] [Level 5]