Definition/Introduction

Organizational culture (OC) is composed of beliefs and expectations shared by members of an organization.[1] Organizational culture consists of common norms, values, and beliefs of individuals within that group.[2] In a historical context, this could be considered the cultural equivalent of the rituals, rites, symbols, and stories of a people.[3] By today’s standards, organizational culture usually refers to the mutual outlook, assumptions, and standards of an organization’s membership. Organizational culture determinants include an organization’s structure, leadership, mission, and strategy.[4] Organizational culture can give employees a feeling of unity and purpose and can help a team cope with complex and dynamic changes.[5] A strong organizational culture can serve as an asset in helping team members accomplish goals and to experience fulfillment in their careers.[4] In fact, an analysis of a company’s OC can be a predictor of factors such as job satisfaction, employee commitment to the organization, or the likelihood of success of a quality improvement initiative.[3]

Culture can be framed through various lenses. For example, one framework is Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, which contends that culture is based on the dimensions of masculinity, power distance index, uncertainty avoidance, and pluralism.[6][3] The Competing Values Framework (CVF) is one framework that has been used in the healthcare organization’s culture assessments and will be discussed in more detail in this article.[3]

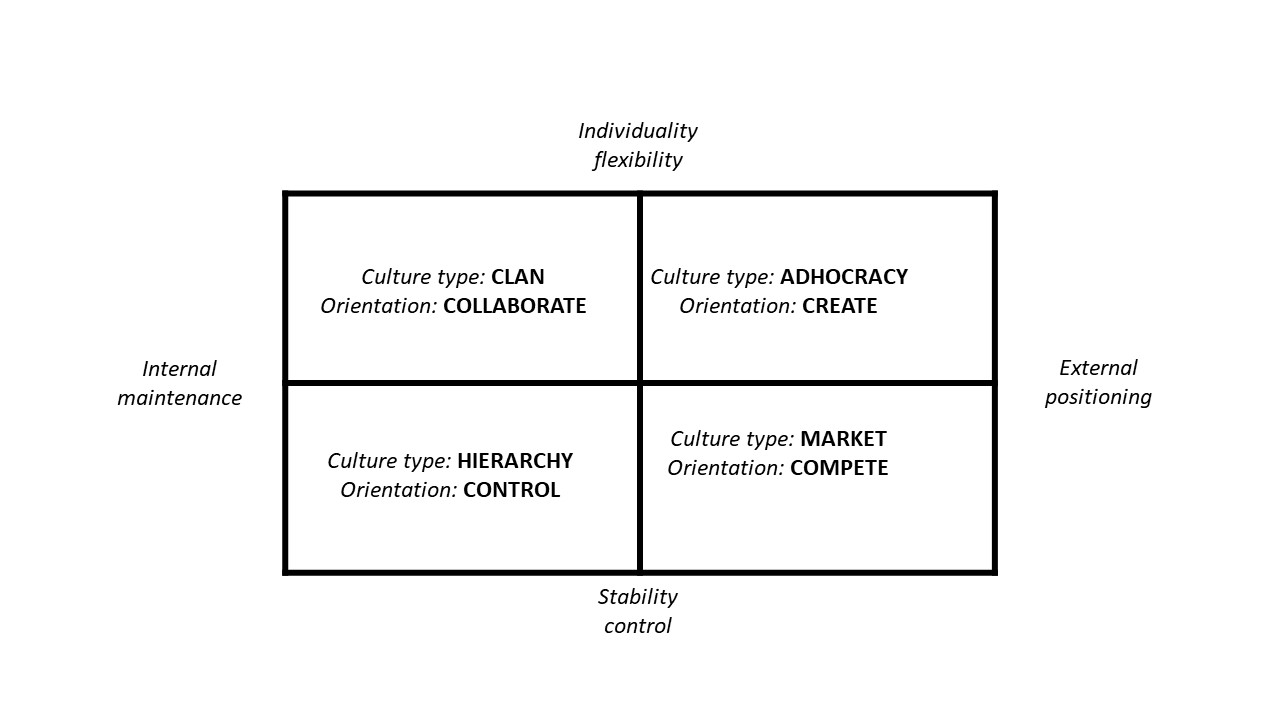

The CVF is made of two axes or dimensions which serve as a foundation for four types of ideal culture.[7][8][3] It can be used to see where an organization’s OC falls along the axes and which ideal culture describes that OC. The horizontal axis is an indicator of the degree of an organization’s effectiveness based on internal emphasis and integration on one side of the spectrum versus external emphasis and differentiation on the other side.[7] The vertical axis assesses an organization’s effectiveness based on a commitment to control and stability versus its effectiveness based on change and flexibility.[7] Each of the four quadrants represents one of the four ideal culture types, as shown in Figure 1 and discussed below: clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market.[7][9][8][3]

Clan

Clan culture, also referred to as group culture in some literature, is built on cooperation. It places a lot of emphasis on building and creating solid and stronger teams with high morale. It is committed to developing and mentoring people in the organization and listening to their input.

Market

The market culture emphasizes competition and is driven to achieve a market advantage. It prioritizes achieving goals of high productivity and profitability.

Adhocracy

In an adhocracy culture, creativity is a prime characteristic built on an entrepreneurial and innovative spirit. This culture thrives in an environment that is agile and transformative.

Hierarchy

A hierarchical culture’s focus is control, which is achieved by monitoring, structure, and organization. Repeatability, dependability, and standardization are the usual aims and descriptors associated with this culture.

The CVF can be very useful when applied to the organizational culture of a healthcare organization. Every organization has elements of each ideal culture type. The CVF can be applied to assess the degree to which each ideal culture is represented in an organization relative to the other types - this can be valuable in the formulation of hypotheses regarding how organizational culture will influence factors like the successful implementation of quality improvement initiatives or achieving certain organizational outcomes.[3] For example, an organizational culture high in group culture will likely result in high satisfaction scores from physicians, who value a strong work ethic and making contributions to the team. In contrast, an OC high in hierarchical culture will likely result in low satisfaction scores from physicians because such an OC is perceived to limit independence and decision-making ability with regards to patient care.[5]

Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument

The organizational culture assessment instrument (OCAI) is a commonly used tool and is related to the Competing Values Framework and attributed to Kim S. Cameron and Robert E. Quinn at the University of Michigan.[10] The tool is composed of six domains, each with four descriptions to choose from to describe the current culture. The domains are “Dominant Characteristics, Organizational Leadership, Management of Employee, Organization Glue, Strategic Emphases, and Criteria of Success.”[10] Responses to the OCAI corresponds to the four distinct OC types. This tool could be used to establish the current OC and be used as a baseline to strengthen the current culture or determine future culture goals. While some studies have found OCAI to be a reliable and valid instrument, others have mixed results.[11][10]