Continuing Education Activity

Morphea, also called localized scleroderma, is a rare inflammatory skin condition that can also affect the subcutaneous tissues. Morphea encompasses multiple variants with different outcomes ranging for small isolated benign skin lesions to aggressive lesions, which can cause significant deformities. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of morphea and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology of morphea.

- Describe the pathophysiology of morphea.

- Summarize the treatment of morphea.

- Outline the importance of improving care coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance the care of patients with morphea.

Introduction

Morphea, also referred to as localized scleroderma, is a rare inflammatory disease of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. It has been reported in both kids and adults with equal frequency. Morphea encompasses a wide spectrum of clinical variants ranging from solitary skin lesions with minimal discomfort to severe subtypes like generalized or linear morphea.

Morphea symptoms are usually limited to the skin and the subcutaneous tissue. Still, extracutaneous involvement is reported in approximately 22% of patients, with linear and generalized subtypes in a cohort reported by Zulian et al. Localized scleroderma can rarely cause debilitating lesions, which result in joint contractures, limb growth defects, and other extracutaneous features in children.

Morphea encompasses a wide variety of clinical phenotypes, which makes its classification challenging. The most commonly used classification was described by Laxer and Zulian, which includes circumscribed morphea, linear morphea, generalized morphea, pan-sclerotic and mixed subtype. Circumscribed morphea is the most common variant and further differentiated into superficial and deep variants. In one cohort study, circumscribed morphea was responsible for 60-65% of the patients. The liner morphea includes the limb or head variant based on the location of the lesion.

One of the most current classifications was developed in 2017 by the European dermatology forum (EDF). The predominant subtypes of the disease distinguished in the EDF classification are generalized type, limited type, linear type, deep type, and mixed type.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The etiology of morphea is unclear, but genetic predisposition, autoimmune dysregulation, and environmental factors play a role in the pathogenesis of morphea. The strongest genetic associations with morphea were found with the HLA class II allele DRB1*04:04 and class I allele HLA–B*37. The presence of auto-antibodies like antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-single-stranded DNA (SS DNA), and anti-histone antibodies supports the role of autoimmune dysregulation.

There is evidence from cohort studies that family members of morphea patients have an increased incidence of other autoimmune diseases, which also suggests the role of autoimmune dysregulation.

Multiple environmental factors like trauma, radiation, and friction have been reported to play a role in morphea. Radiation can cause localized secretion of interleukin 4 and 5, which induce TGF-B mediated fibrogenesis.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Morphea is a rare skin condition, and the incidence rates vary from 3.4 to 27 per 100,000, and women are more susceptible than men.[6] Women have higher rates of morphea at 2.5 to 5:1 compared to men and are usually affected in the fourth decade of life.

The peak incidence of morphea in children is reported to happen between 7 and 11 years.

Morphea incidence is reported to be 2-3 per 100,000 in the United States. Morphea is reported to occur more frequently in Whites compared to the African American population.[7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of morphea is vague, but there is evidence supporting the role of autoimmune dysregulation with abnormal cytokine production and vascular dysfunction in morphea. Excess collagen deposition in the dermis also plays a crucial role in morphea.

Multiple external factors like trauma, environmental exposures, and radiation therapy can trigger and contribute to the onset of morphea.

The role of immune dysregulation is confirmed by the presence of inflammatory infiltrates in skin biopsies laden with eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. IL-4 cytokine is detected at higher levels in patients with morphea. Also, patients with generalized morphea often test positive for ANA and other autoimmune antibodies.

There is an increased presence of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) and intracellular cell adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) in patients with morphea, which facilitate the recruitment of T lymphocytes in the acute phase.

CD-4 T helper cells play a significant role by producing IL-4 cytokine, which causes the upregulation of TGF-B. TGF-B stimulates fibroblast production of collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins.[8][9]

Histopathology

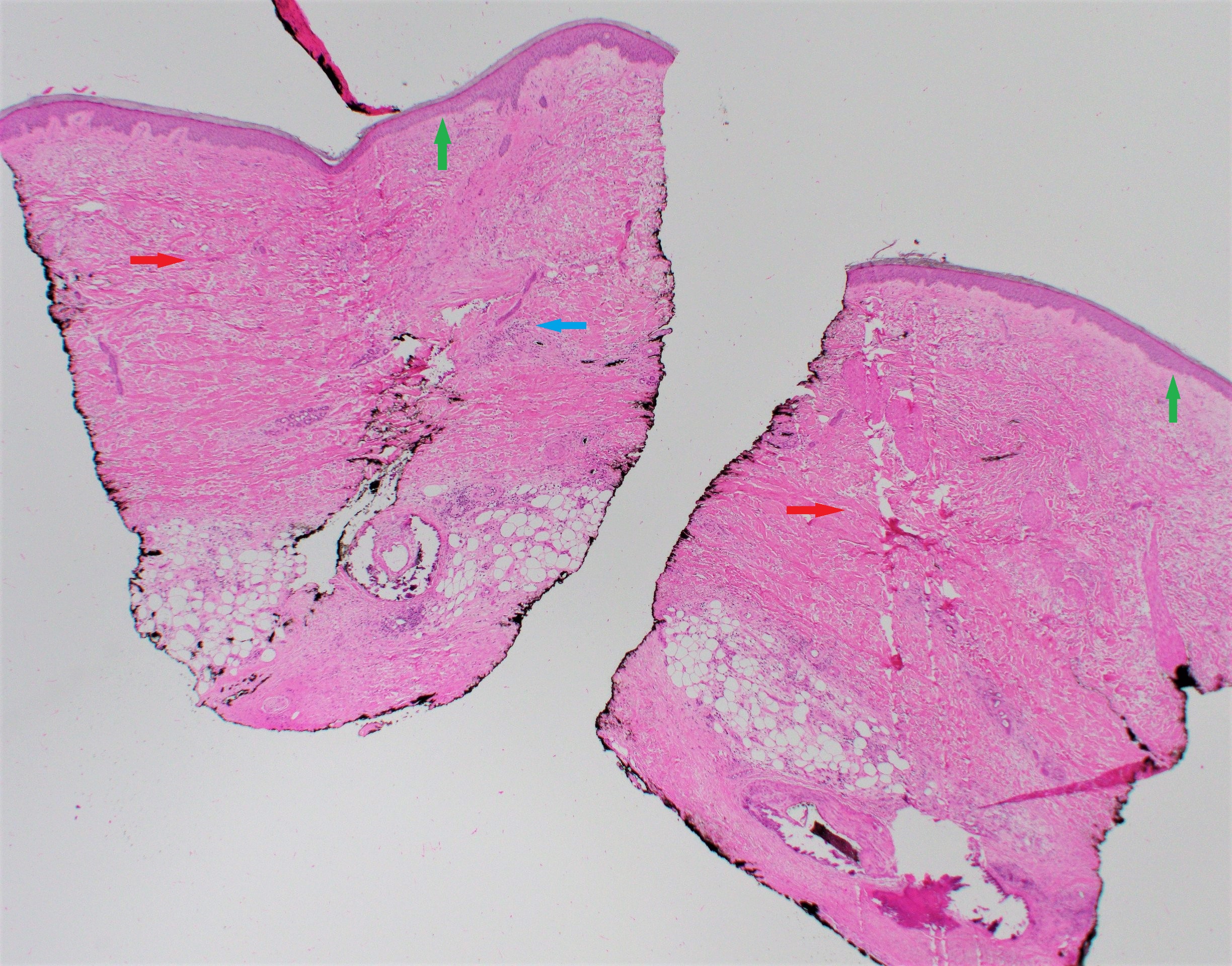

Histopathologic findings are helpful to confirm a diagnosis and correlate with the clinical state of morphea. A punch biopsy is recommended, and it should include the subcutaneous fat for appropriate tissue diagnosis.

In new lesions, a biopsy of the inflammatory border reveals a perivascular infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells, with some eosinophils and macrophages. Older sclerotic lesions demonstrate collagen bundles extending into the reticular dermis, enclosing the eccrine glands and blood vessels.

Eosinophilic fasciitis lesions demonstrate thickened fascia infiltrated with lymphocytes, eosinophils, and macrophages. Histopathologic findings also help to exclude other fibrosing disorders like scleromyxedema, myxedema, radiation dermatitis, amyloidosis, chronic graft-versus-host disease, lipodystrophy, sarcoidosis, and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.

History and Physical

Morphea is classified into various subtypes, and clinical presentation varies with each phenotype.

Early lesions of morphea present as erythematous skin lesions with some itching and tenderness. As the lesions progress, they develop sclerotic centers surrounded by a violaceous border. The lesions eventually result in hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation with atrophy of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. In most patients, the lesions are self-limiting and resolve in a few years, but some patients can develop new lesions with ongoing symptoms.

Circumscribed morphea presents as isolated oval or round lesions over the trunk or chest. The superficial variant tends to be mild, with inflammation localized to the dermis. In the deep variant, the inflammation spreads to the cutis and involves the fascia and the muscles and results in scarring. A deep variant can often cause complications like joint contractures.

Linear morphea is characterized by the presence of band-like lesions, which usually manifest over the head and neck or the limbs. The sclerosis is localized to the dermis but often has a protracted course and is the most common type in childhood-onset morphea. It can involve deeper tissues causing complications like muscle weakness, joint contractures, and limb deformities in children.

Morphea that is the “en coup de sabre” (the blow of a sword) type causes a lesion over the forehead and extends over the scalp leading to alopecia. The patients with deeper lesions can develop ocular and neurologic symptoms like headaches and seizures and very rarely develop progressive hemifacial atrophy.

Generalized morphea is a severe form of plaque morphea characterized by multiple lesions or coalescence of individual plaques. It is predominant in females, and the lesions are frequently deep and associated with limited range of motion in underlying joints. Generalized morphea is defined by the presence of more than four lesions in at least two different anatomic locations.

There are other variants like bullous and guttate morphea, which are very rare. Other clinical entities like eosinophilic fasciitis and Parry Robertson syndrome are often considered to be related to morphea.

Mixed morphea is a term used to describe the simultaneous presence of more than one subtype.[10]

Evaluation

Morphea is usually a clinical diagnosis and can be confirmed by physical examination. However, some patients need a skin biopsy, including subcutaneous fat, to confirm the diagnosis of morphea. In deeper skin lesions, an incisional biopsy is required to get an appropriate tissue sample for histopathology.

There are no morphea specific antibodies; however, positive ANA, anti-histone Ab, and SS DNA Ab are reported in some patients. In one case-control study, 30% of morphea patients had a positive ANA compared to 11% in the control population. Other laboratory findings like peripheral eosinophilia on complete blood count (CBC) and elevated inflammation markers may help in the diagnosis. However, in morphea patients with positive ANA and Raynaud’s symptoms, it may be warranted to screen for systemic sclerosis.

In patients with severe lesions, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging is useful to understand the depth of the lesions and look for findings like thickening of the fascia, tenosynovitis, or myositis, which can cause serious deformities. Ultrasound is also good alternative imaging to use in regular disease monitoring.[11][12]

Treatment / Management

Clinicians should review the subtype of morphea, the depth of involvement, and disease activity, which play a significant role in treatment decisions. Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary to minimize damage such as cosmetic sequelae and joint contractures or limb deformities in patients with severe forms of morphea.

In patients with superficial circumscribed lesions, topical treatments are appropriate and offer an excellent therapeutic response. Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for superficial morphea, and the usual treatment is for 3-4 weeks. Topical tacrolimus 0.1% is an alternate choice for superficial circumscribed morphea.[13]

For patients with more widespread lesions and deep morphea, the first-line treatment is phototherapy with ultraviolet A1 (UVA1). Lower wavelength phototherapy ultraviolet A (UVA) has greater tissue penetration than ultraviolet B (UVB) and has a low risk of sunburn. If UVA1 is not available, other options for phototherapy include broadband UVA, narrowband UVB, and PUVA (psoralen and long-wave ultraviolet A).[14] Phototherapy is ineffective for morphea involving the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, or bone.

Patients who do not have access to UVA therapy can be treated with high potency topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroids, or topical tacrolimus.

Rapidly progressive lesions require treatment with systemic therapy with corticosteroids or methotrexate. Oral or IV corticosteroids have shown to be effective in treating morphea, but symptoms relapse after discontinuation of treatment. For patients in this category, the combination of methotrexate and systemic corticosteroids is considered first-line treatment.[15][1] [1][16] Mycophenolate mofetil can be used as an alternative to methotrexate.

Surgical treatments like autologous fat grafting can be considered in patients with en coup de sabre.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

It is vital to differentiate morphea from systemic sclerosis due to its systemic organ involvement and bad prognosis with delay in diagnosis. Patients should be evaluated for the presence of Raynaud's phenomenon, sclerodactyly, calcinosis cutis, and telangiectasia, which warrants further testing for systemic sclerosis with serologies, capillaroscopy, and pulmonary testing.

It is also important to differentiate morphea from other fibrotic skin conditions like scleromyxedema, lipodermatosclerosis, and post-irradiation morphea. Sclermyxedema is seen in patients with systemic diseases like plasma cell dyscrasias. Skin biopsy shows a diffuse deposit of mucin composed primarily of hyaluronic acid in the upper and mid reticular dermis.

Radiation-induced morphea is a rare and chronically progressive localized scleroderma after radiation.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Methotrexate is a commonly used disease-modifying agent due to its anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects. Extensive studies have demonstrated methotrexate inhibits DHFR and AICAR transformylase, which are the major mechanisms of action. It is important to screen patients for hepatitis B and C before initiating methotrexate.

Patients who take methotrexate need a complete blood count and the comprehensive metabolic panel every three months to monitor for methotrexate toxicity, which can cause cytopenias and elevate liver function tests. Patients on methotrexate are prescribed folic acid supplements to prevent side effects like nausea, mucositis, and hair thinning due to folate depletion.

Patients who are on long term corticosteroids should be screened for side effects like osteoporosis with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan.

Prognosis

Patches of morphea that are superficial may be relatively benign, and the prognosis is good. Still, some variants of morphea tend to involve subcutaneous tissue, muscle tissue, and bone, resulting in functional disabilities and cosmetic problems. Many children with linear morphea can develop joint contractures and limb length discrepancies.

Complications

Morphea lesions can cause cosmetic sequelae if untreated, but internal organ involvement is rare. Linear morphea in children can cause severe atrophy of the extremities with joint contractures and limb length discrepancies. In the en coup de sabre variant, the inflammation and sclerosis involve deeper tissues and cause hemiatrophy of the face and facial deformity. Patients should be regularly monitored for side effects of medications like methotrexate with appropriate lab tests every three months.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Morphea is a rare skin disorder that can affect both children and adults with equal frequency. Autoimmune dysregulation plays a role in the etiology of morphea, but patients should be educated about external factors like trauma, radiation, and friction in morphea. Genetic predisposition is considered to play a role in etiology, and studies show that family members of morphea are at higher risk of other autoimmune diseases.

Patient education helps them to make informed decisions about the treatment options and prognosis of morphea. Patients who are being prescribed medications like corticosteroids, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil should be referred for pharmacy education about common side effects, contraception and medication interactions to improve compliance.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Morphea encompasses a wide variety of phenotypes that range from benign isolated lesions to deep forms of morphea, which can have a poor prognosis. Unfortunately, this makes diagnosis challenging, and there is no consensus in classification, which can result in delayed diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

A coordinated effort of health care providers that includes primary clinicians, dermatologists, and rheumatologists is necessary for early diagnosis and treatment. It is essential to do appropriate testing to differentiate morphea from systemic sclerosis, which has a poor prognosis due to systemic organ involvement. It is also important to get an appropriate histopathologic diagnosis to understand the diagnosis and rule out other fibrotic skin disorders.

Methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil can cause significant side effects in pregnant patients, so appropriate pharmacy education on contraception, medication interactions, and toxicity monitoring help improve patient compliance with these medications and prevent side effects.