Continuing Education Activity

Lagophthalmos describes the incomplete or abnormal closure of the eyelids and has many different causes. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of lagophthalmos and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and improving the care of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology and epidemiology of lagophthalmos.

- Describe the appropriate history, physical, and evaluation of lagophthalmos.

- Explain the management options available for lagophthalmos.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance lagophthalmos and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Lagophthalmos describes the incomplete or abnormal closure of the eyelids. A full eyelid closure with a normal blink reflex is necessary for the maintenance of a stable tear film and healthy ocular surface. Patients who are unable to blink and completely close their eyes are at risk of corneal exposure, evaporation of the tear film, and subsequent exposure keratopathy. This can progress to corneal ulceration and perforation. Therefore it is essential to recognize the signs of lagophthalmos early and investigate the causes and begin treatment. The primary cause of lagophthalmos is facial nerve paralysis, which leads to paralytic lagophthalmos.[1]

There are many etiologies associated with facial nerve paralysis; hence a detailed history and workup are necessary to determine treatment of the underlying cause. The purpose of treating lagophthalmos is two-fold: to prevent further corneal exposure and to improve eyelid function. Any asymmetry in a person's face will likely have a psychological impact. Therefore the patient needs to regain an appearance acceptable to themselves.[2]

Treatment can be divided into medical and surgical modalities. Medical treatment consists of improving the quantity, quality, and stability of the tear film. Surgical procedures can be dynamic or static and focus on reestablishing eyelid function or eyelid coverage. The choice of treatment and reconstruction method will depend on the location, severity, etiology of lagophthalmos, as well as patient factors of age, health, and their expectations.

Etiology

Paralytic Lagophthalmos

Facial nerve paralysis is the cause of paralytic lagophthalmos, of which there are many underlying aetiologies outlined below.

Infection:

- Otitis (external, otitis media)

- Mastoiditis

- Viral (herpes simplex, herpes zoster, influenza, coxsackievirus, polio, mumps, mononucleosis)

- Bacteria (Tuberculosis, syphilis, leprosy, cat scratch disease, Lyme disease, botulism)

- Fungal (Mucormycosis)

- Immunocompromised (AIDS)

Trauma:

- Facial injuries

- Birth trauma

- Fractures to the skull base, temporal bone fracture

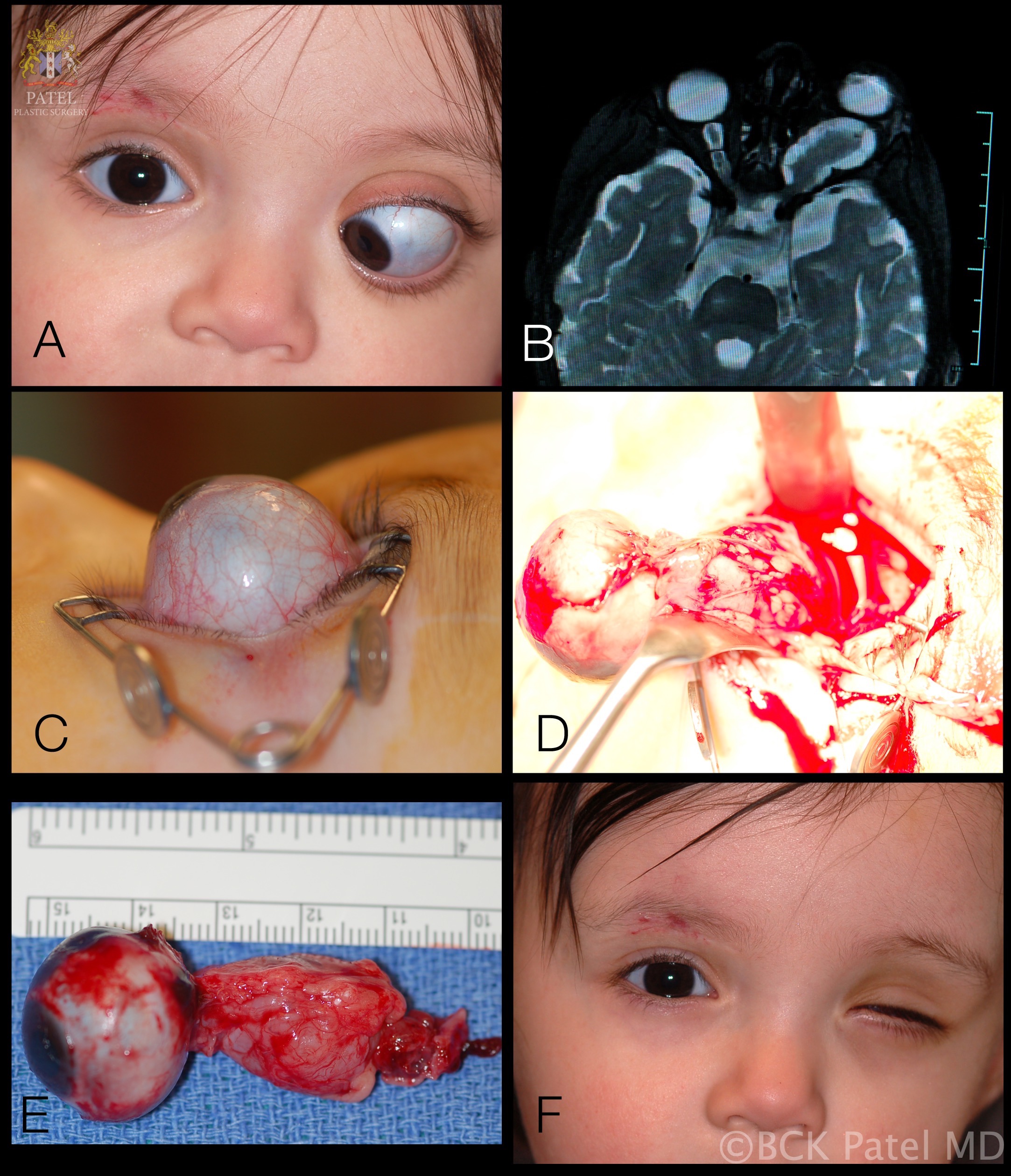

Tumour:

- Parotid lesion

- Cholesteatoma

- Facial nerve tumor

- Schwannoma

- Teratoma

- Neurofibromatosis Type 2

- Fibrous dysplasia

- Haemangioblastoma

- Acoustic neuroma

- Sarcoma

- Leukemia

- Meningioma

- Carcinoma (primary or metastatic)

Metabolic:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Vitamin A deficiency

- Hyperthyroidism

Toxic:

- Thalidomide

- Alcohol excess

- Arsenic

- Tetanus

- Diphtheria

- Carbon monoxide

Iatrogenic:

- Parotid surgery

- Mastoid surgery

- Post-immunization

- Post-tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy

- Embolization

- Mandibular block anesthesia

- Antitetanus serum

- Dental surgery

- Eyelid surgery (excessive tissue removal from blepharoplasty)

- Squint surgery (vertical muscle recession surgery)

Neurological:

- Millard-Gubler syndrome

- Foix-Chavany-Marie syndrome

Congenital:

- Mobius syndrome

- Goldenhaar syndrome

- Ichthyosis

Idiopathic:

- Bell's palsy

- Amyloidosis

- Temporal arteritis

- Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myasthenia gravis

- Sarcoidosis

- Osteopetrosis

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Hereditary hypertrophic neuropathy

- Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome

Cicatricial Lagophthalmos

Lagophthalmos is due to scarring to the eyelids. The upper and lower eyelids consist of seven structural layers. From anteriorly, these are skin and subcutaneous tissue, orbicularis oculi, orbital septum, orbital fat, retraction muscles, tarsal plate, and conjunctiva. Injury to any of these tissues can cause incomplete eyelid closure. Causes include:

- Solar elastosis

- Chemical burns

- Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid

- Steven-Johnson syndrome

- Trauma

Nocturnal Lagophthalmos

Lagophthalmos, which occurs during sleep, is termed nocturnal lagophthalmos and can cause similar symptoms of dry eyes and exposure keratopathy. The diagnosis can be challenging as there is clinical overlap with blepharitis, and the patient may not be aware of lagophthalmos during slumber. Patients can report insomnia, and exacerbated symptoms upon waking, either in the morning or during the night.

Incomplete Blink and Lagophthalmos

An incomplete blink with consequent lagophthalmos is seen in patients with Parkinson disease and ocular myopathies like myotonic dystrophy and chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia.

Epidemiology

Facial nerve paralysis occurs in 30 to 40 people per 100,000 annually in the United States.[3] The most common cause is Bell palsy and is responsible for up to 80% of cases. Bell palsy is an acute, unilateral facial nerve paralysis that resolves spontaneously over time. There is no known cause; however, it may have an association with viral infections. Symptoms experienced can include earache, hyperacusis, deafness, taste alterations, paresthesia of the cheek, mouth, and ocular pain. Fortunately, there is an excellent prognosis, with up to 84% of patients recovering full function of their facial nerve.[4]

Pathophysiology

Eyelid retraction is usually acquired and associated with thyroid eye disease.[5] The Müller muscle is stimulated and results in a bilateral asymmetric stare in hyperthyroid patients. Lymphocyte and mast cells can infiltrate the Muller muscle and levator, with secondary fibroblastic proliferation, which leads to the classic appearance of superior temporal eyelid retraction (lateral flare).[6]

Facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) paralysis from any cause will result in lagophthalmos (without eyelid retraction). The more common etiologies include Bell palsy, sarcoidosis, cerebral ischaemic event, and post-surgical tumor excision. Orbicularis oculi paralysis will lead to the unopposed action of the levator. For the lower lid, this will cause loss of tonus, which will result in a scleral show and a progressive ectropion. Epiphora (tearing) occurs due to lacrimal pump malfunction and increased reflex lacrimal secretion secondary to corneal exposure.[7]

History and Physical

The clinical history is very important and should aim to determine the underlying etiology of the lagophthalmos. If the patient had recent surgery or trauma to the eye, orbit, face, or head, then this should be ascertained. Previous infections in history should be reviewed, especially if it was herpes zoster. A detailed medical history will help to reveal any systemic causes, such as thyroid disease or obstructive sleep apnea. The history of acute facial nerve paralysis is a sudden unilateral loss of facial motor function. This results in a distinctive facial asymmetry.

If the lesion is the lower motor neuron, then the complete hemiface is affected; upper motor neuron lesions will spare the frontalis muscle, and hence the forehead is not affected. For a lower motor neuron lesion causing complete facial paralysis, patients will have a loss of forehead, nasolabial folds, ptosis of the eyebrow, lower lid ectropion, upper lid retraction, lagophthalmos, oral droop, problems with speech, and possibly emotional distress due to the physical effects.

Evaluation

Clinical Examination

The patient should be observed for external signs such as incomplete blink, exophthalmos, eyelid malposition, degree of Bell's phenomenon. The degree of lagophthalmos can be measured by asking the patient to close their eyes and checking if there is a space between the upper and lower eyelid margins. If there is lagophthalmos, the vertical height at the greatest distance of the palpebral fissure should be measured, and any scleral or corneal show documented. All cranial nerve function should be then examined, especially those governing ocular motility and the orbicularis oculi muscle.

On the slit lamp, the conjunctiva should be assessed for injection or chemosis, followed by examination and testing the cornea for sensitivity. The presence of punctate epithelial erosions or epithelial defects can be highlighted with fluorescein staining, with special attention focussed on the inferior cornea where lid excursions terminate. The tear breakup time should be recorded.

Further Investigations

Laboratory and imaging studies are determined based on what the underlying etiology could be. If there is suspicion of thyroid eye disease, thyroid function tests along with CT orbital imaging may become necessary in the presence of exophthalmos. If there are fluctuating and progressive neurological signs, then CT/MR neuroimaging is indicated to rule out hemorrhage or tumor.

Treatment / Management

Management of lagophthalmos involves both medical and surgical approaches with the aim of treating the underlying condition leading to exposure keratopathy and protection of the ocular surface.

Medical

Artificial tears without preservatives can be administered frequently in order to improve the patient's tear film. The ointment can be applied at night time or during the day if there is severe corneal exposure. Taping of the eyelids at night can offer additional ocular surface protection without resorting to surgery.[8] There are also moisture chamber-type glasses which can aid in maintaining a stable tear film and improve symptoms.[9] The volumizing hyaluronic acid gel has been used for tissue expansion for immediate management of cicatricial ectropion in cases of lagophthalmos e.g. congenital ichthyosis.[10]

Surgical

A stepwise approach is recommended based on the severity and duration of the lagophthalmos. A close follow-up with the frequent examination is necessary.

Tarsorrhaphy

When there is corneal exposure and recovery is expected within a matter of weeks, a temporary tarsorrhaphy can be a good option. In the majority of cases, the cornea can be protected adequately by closing the lateral one-third of the eyelids. A small opening should remain so that the cornea can be continuously assessed and required topical medications can be administered. Loosening of the sutures can occur over time, resulting in inadequate ocular surface protection. Complications include trichiasis and poor cosmesis from scarring.

Gold/Platinum Weight Implantation

If there is no full lid closure, gold or platinum weight can be implanted into the upper eyelid in patients with paralytic lagophthalmos. This will result in a gravity-dependent enhancement of eyelid closure.[11] Gold was initially used because it is inert. Platinum has a higher density which translates to a slimmer profile, decreased visibility, and improved cosmesis. It is also less likely to induce inflammatory reaction compared to gold, and decreased rates of extrusion. [12] Preoperatively the correct weight is chosen by taping weights onto the external lid superior to the tarsus and observing the effect on eyelid closure. The ideal weight should allow for full lid closure, opening, and avoid ptosis in primary gaze.

Upper Eyelid Retraction and Levator Recession

Patients with lagophthalmos secondary to upper eyelid retraction (i.e. from thyroid eye disease) can have recession surgery of the upper eyelid retractor muscles (levator palpebrae superioris and Müller’s muscles). Full-thickness skin grafts or advancement flaps can be options for patients with postsurgical lid shortening e.g. after upper lid blepharoplasty. In addition, scar band releases and tarsal-sharing procedures can be suitable for cicatricial lagophthalmos.[13]

Lower Eyelid Tightening and Elevation

Lower eyelid laxity occurs in facial nerve paralysis and floppy eyelid syndrome. Lid tightening procedures such as lateral tarsal strip will lead to improved apposition of the lower eyelid to the globe and decrease scleral exposure and epiphora symptoms.[14] If there is persistent corneal exposure after medical therapy and upper eyelid surgery, lower eyelid elevation with retractor muscle recession can be an option. A spacing graft from the autologous ear, nasal cartilage, or hard palate grafts can be sutured in place to achieve further elevation.[15][16] If there are cicatricial changes a full-thickness skin graft and/or mucous membrane graft could be needed.[17]

Ancillary Surgical Procedures

Severe lagophthalmos secondary to facial nerve paralysis may require midface elevation. This can be achieved with a variety of techniques, such as using autogenous fascia slings. Other approaches to reanimate the face include temporalis muscle transposition, nerve grafts, palpebral springs, suborbicularis oculi fat lifts, and soft tissue repositioning.[18]

Differential Diagnosis

Bell's palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion; more serious causes of facial palsy will need to be ruled out. The more serious causes are listed in the etiology section of this article. It is important to consider whether the lesion location is lower or upper motor neuron. Bilateral cortical innervation of the upper facial muscles will result in complete facial paralysis for lower motor neuron lesions in most cases. Therefore asking the patient to raise their eyebrows is very useful in assessing the functions of frontalis and orbicularis oculi. Lower motor neuron lesions include Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Upper motor neuron lesions causing facial nerve paralysis include cerebral ischaemic event, multiple sclerosis, intracranial hemorrhage, or neoplasia. An atypical presentation, recurrent or progressive symptoms, additional neurological findings, lack of spontaneous resolution, and/or history of head, neck, or cutaneous malignancy are risk factors necessitating further workup.

Prognosis

The prognosis of lagophthalmos depends on the underlying etiology. Mild exposure keratopathy has a very good prognosis, especially if due to Bell's palsy, in which the majority of patients have spontaneous resolution. Severe cases can lead to corneal scarring, perforation, and visual loss.

Complications

Complications can range from relatively mild, involving dry eye signs and symptoms, to corneal abrasions, persistent epithelial defects, ulceration, microbial keratitis, and corneal scarring. Corneal perforation can occur leading to visual loss. Band keratopathy can occur as a result of chronic exposure keratopathy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

There are multiple challenges for patients with lagophthalmos with which to cope with. Patient education is vital to reduce complication risks with self-management regimes. These mainly consist of managing dry eyes, lid taping technique, and if due to facial palsy additional factors such as eating and drinking, speech, facial expression, and psychological impact. Providing patients with relevant educational material, and also directing them to support groups can be beneficial to patients' wellbeing and outcome.

Pearls and Other Issues

Facial nerve paralysis is the main cause of lagophthalmos. There are several grading systems in use, with the House-Brackmann grading scale (HBGS) being widely used as a measure of facial nerve function.[19] Patients with grade 1 to 3 have full eyelid closure and those with grade 4 to 6 are at risk of exposure keratopathy. Alternative grading scales include the Sunnybrook and Yanagihara systems, which have been found to score at the same agreement level.[20]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multi-disciplinary team approach is required for timely accurate patient evaluation, management, and long-term rehabilitation of patients with lagophthalmos. Members of the team can include emergency, stroke, and family physicians, ophthalmologists, ENT surgeons, radiologists, neurologists, maxillofacial surgeons, nursing staff, speech therapists, dieticians, pharmacists, and physiotherapist.

Presentation of lagophthalmos due to different etiologies can present to an emergency as well as primary care staff, hence familiarity with the assessment and management is essential for clinicians. Nursing staff working on head and neck wards will need to recognize the signs and symptoms of facial nerve paralysis. Pharmacists will need to verify all dosing, medication checks, and liaise with medical staff in administering the medication. Rehabilitation will closely involve physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, and dieticians in patients with lagophthalmos secondary to facial nerve paralysis. A psychologist can also aid the patient's recovery from the psychological impact of facial nerve paralysis.[21] An interdisciplinary approach can provide a holistic and integrated management system in lagophthalmos patients and lead to improved outcomes. [Level 5]