Continuing Education Activity

Hypovolemia refers to a state of low extracellular fluid volume, generally secondary to combined sodium and water loss. All living organisms must maintain an adequate fluid balance to preserve homeostasis. This activity outlines the clinical manifestations, causes, and management of hypovolemia and highlights the interprofessional team's importance in evaluating and treating this pathology.

Objectives:

- List the various etiologies of hypovolemia.

- Describe the evaluation of a patient with hypovolemia.

- Discuss the treatment and management of hypovolemia.

Introduction

Hypovolemia refers to a state of low extracellular fluid volume, generally secondary to combined sodium and water loss. All living organisms must maintain an adequate fluid balance to preserve homeostasis. Water constitutes the most abundant fluid in the body, at around 50% to 60% of the body weight. Total body water is further divided into the intracellular fluid (ICF), which comprises 55% to 75%, and the extracellular fluid (ECF), which comprises around 25-45%. The ECF is further divided into the intravascular and extravascular (interstitial) spaces. ECF is the more readily measured component as it can be estimated by arterial blood pressure.

Etiology

The causes of hypovolemia are broadly divided into renal and extrarenal etiologies.

Renal

- Diuretic excess

- Mineralocorticoid deficiency

- Ketonuria

- Osmotic diuresis

- Cerebral salt wasting syndrome

- Salt-wasting nephropathies

Extrarenal

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Third spacing of fluid

- Burns

- Pancreatitis

- Trauma

- Bleeding[1]

Epidemiology

The incidence of hypovolemia in the general population is hard to quantify. In the acutely ill patient, hypovolemia is one of the most common manifestations. With critically ill patients, requiring intensive care, it is more common where loss by exsanguination, fluid shifts, stress, and other etiologies play a role.

History and Physical

Establishing the etiology of a patient's hypovolemia is of utmost importance to properly tailor management. Hypovolemia usually is the result of a primary disorder and clinical manifestations are closely related to the primary cause. Symptoms are usually non-specific and include weakness, fatigue, dizziness, muscle cramps, and thirst. Physical examination findings are dry mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor, orthostatic tachycardia, and hypotension. Vital signs consistent with hypovolemia are hypotension and tachycardia. There is a risk of the patient's hypovolemia evolving into shock which would present with peripheral vasoconstriction, cyanosis, oliguria, and altered mental status.[2]

Evaluation

Clinal Evaluation and Static Hemodynamic Measures

Clinical signs, such as hypotension, tachycardia, and dry oral membranes, along with laboratory findings, such as blood urea nitrogen, serum and urine sodium, hematocrit, and blood gas measurements, help to elucidate the underlying etiology of hypovolemia. The simplest and fastest means of evaluating hypovolemia remains arterial blood pressure measuring. Advanced hemodynamic parameters such as cardiac filling pressures, such as CVP, and volumetric preload parameters such as intrathoracic blood volume index, ITBVI have been used to approximate cardiac preload and to appropriately guide fluid resuscitation.[3] Passive leg raise is a simple test to evaluate the volume status in these patients but is cumbersome to perform.

Point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS)

Point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) is a safe, non-invasive, and readily available means of estimating volume status. Central venous pressure can be estimated by assessing the inferior vena cava or internal jugular vein diameter and collapsibility. Hypotension has a broad differential diagnosis and poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. POCUS can rapidly assess volume status and measure specific parameters that aid in the diagnosis of the etiology underlying the patient's hypovolemia. Also, POCUS can serve as a measure of response to fluid resuscitation and guide treatment. One way this can be done is by measuring the respiratory variation in the inferior vena cava. However, this has not been validated in patients without spontaneous breaths or arrhythmias and should not be used as the only means of assessing volume status and response to fluid resuscitation.[4][5] Stroke volume variation calculations by measuring Velocity time integral (VTI) and Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter are more accurate and help determine the volume status in mechanically ventilated patients. Superior Vena cava (SVC) distension and variability can also be used in mechanically ventilated patients to assess volume status but requires Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE).

Dynamic Hemodynamic Measures

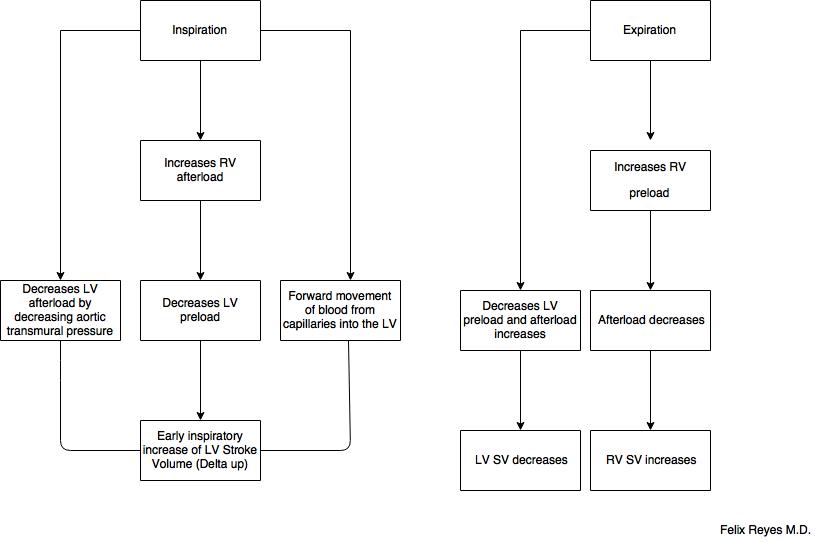

Dynamic hemodynamic parameters are more precise in determining the etiology of hypovolemia and response to fluid replacement. Using changes in preload and right atrium pressure, arterial blood pressure, pulse pressure, or stroke volume we can calculate the systolic pressure variation, pulse pressure variation, and stroke volume variation. It is important to specify some conditions that may decrease the reliability of these calculations:

- Arrhythmias

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Increased intraabdominal pressure

- Heart failure

- Vasopressors

Of importance is that these indices are of clinical value only if the patient is mechanically ventilated. The mechanism of breathing induced fluctuations in stroke volume and blood pressure are different during spontaneous breathing and mechanical ventilation, which results in inaccurate measurements.[6]

Treatment / Management

The management of hypovolemia is anchored in the chronicity and severity of the patient's presentation. Acute hypovolemic states could quickly lead to shock and will require urgent fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support. Chronic hypovolemic states allow for the development of compensatory mechanisms that permit a more gradual restoration of intravascular volume. Regardless, hypovolemia requires prompt attention and treatment to prevent permanent organ damage and death. Intravenous fluid resuscitation remains the most common intervention for patients in the acute setting. Much discussion has been held on the subject of specific intravenous fluids for resuscitation. Several meta-analyses suggest that colloid solutions may increase mortality. At this time, crystalloid solutions remain the standard of care for fluid resuscitation. In the CRISTAL (Colloids Versus Crystalloids for the Resuscitation in critically ill people) metanalysis the use of colloids compared with crystalloids was associated with similar mortality in patients with hypovolemic shock.[7]

After selecting the appropriate intravenous fluid for replenishment a therapeutic goal must be selected. Several measures can be used to assess volume status and guide therapy. In critically ill patients being taken care of in the intensive care unit, more invasive procedures can be used to monitor more closely the response to therapy, some of these are:

- Insertion of a urinary catheter to measure urine output

- Insertion of an arterial line to measure arterial blood pressure and variations in systolic blood pressure

Once resuscitation targets have been met for hypovolemia, fluids administration should be stopped as excessive fluid resuscitation could lead to fluid accumulating beyond the intravascular space resulting in fluid overload and severe cardiac and pulmonary consequences.[8][9][10]

Differential Diagnosis

Systolic blood pressure measuring is the most readily available means of assessing volume status, therefore; any condition that causes a decrease in systolic blood pressure must be considered among the differential diagnosis for hypovolemia. Some of these are outlined below.

- Pregnancy

- Sepsis

- Hypoglycemia

- Anaphylaxis

- Anemia

- Heart failure

- Bradycardia

- Valvular pathology

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients suffering from hypovolemia depends on the underlying etiology and prompt management of the fluid status. There is a high risk of permanent damage such as cardiac arrhythmias, cerebral hypoperfusion, and multi-organ failure if left untreated. However, in the majority of cases, hypovolemia that is quickly identified and managed with proper fluid resuscitation and addressing the underlying etiology results in a very favorable prognosis.

Complications

- Shock

- Ischemic stroke

- Myocardial infarction

- Liver failure

- Acute Renal failure

- Multi-organ failure

- Death[3]

Consultations

Hypovolemia is a sign of an underlying disorder, therefore, consultations should be tailored to the disease that is causing the hypovolemia. After proper fluid resuscitation and diagnosis of the underlying etiology specialties should be involved to manage the specific disease as needed. In the case of gastrointestinal losses or bleeds, a gastrointestinal disease specialist should be involved to directly treat the source. Nephrologists are usually consulted when renal issues are determined to be the culprit. For trauma patients and burn victims, surgery should be consulted. In cases where patients are not responding to fluid resuscitation, an intensivist may be consulted as these patients may be undergoing hypovolemic shock and require more critical care.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Hypovolemia can have serious consequences, including permanent damage and death. For this reason, the patients should be educated on signs and symptoms of low volume status and to get prompt medical assistance in these situations.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hypovolemia requires a multidisciplinary approach to management to improve patient outcomes. First, patients should be properly triaged by the severity of their presentation. Nurses should be properly trained and comfortable in the administration of intravenous fluids (IV) and other medications needed. Pharmacists should distribute and maintain an adequate supply of intravenous fluids readily available for fluid resuscitation. Finally, the physicians should be comfortable and astute in their management of hypovolemia, with the goal of identifying the underlying disorder and promptly treat it.