Continuing Education Activity

DDH (developmental dysplasia of the hip ) is a disorder that is due to abnormal development of acetabulum with or without hip dislocation. Early diagnosis and management will prevent long term complications like persistent dislocation and early hip osteoarthritis. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the risk factors for the early identification of DDH.

- Describe the evaluation of DDH.

- Review the management options available for DDH.

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) occurs due to an abnormal hip development, which presents in infancy or early childhood with a spectrum ranging from dysplasia to dislocation of the hip joint.

Previously referred to as "congenital dislocation of the hip," the term developmental is preferred since not all are present or are identified at birth. Developmental will be more accurate as it explains the broad spectrum of abnormalities in the hip joint. Presentation varies from minor hip instability to frank dislocation. The exact etiology is still elusive. Multifactorial in nature, a combination of genetic, environmental, and mechanical factors plays a role. This article is focused on healthy babies with DDH, rather than genetic or syndromes which causes teratologic or neuromuscular dysplasia. Many genetic loci have been identified in familial cases.

Early diagnosis and treatment are rewarding to prevent residual DDH, which causes limp, and or early osteoarthritis.[1]

Etiology

The following are the risk factors for DDH include female sex, first-born infant, breech positioning in the third trimester, swaddling, postmaturity, LGA, conditions causing limited in utero space, and family history.

- Female sex: Approximately 4 times that of boys. The increased incidence is probably due to ligamentous laxity from maternal hormones. The odds ratio for the female sex is 4.14 (3.0 to 5.7).[2]

- Breech position in the last trimester is the most significant risk factor for DDH. The odds ratio is 5.47 (2.58 to 11.6). The procedures that decrease the time spent in the breech Position, like the external cephalic version and pre-labor CS, reduce the risk for DDH.[3]

- Family history: Many genes have postulated in the Asian population: COL2A1, DKK1, HOXB9, HOXD9, WISP3. The relative risk is 1.72 (0.05 to 55.00). The risk of recurrence is high approximately 6%. Robert et al.[4] also suggested IL6 and TGFB1(transforming growth factor-beta 1 or TGF-β1) are the two pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis, may be associated with DDH in the caucasian population.[5]

- Swaddling in the adducted and extended position explains the increased incidence in specific populations including American Indians, Japanese and Turkish infants. Many international societies like AAP(American academy of pediatrics, Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America(POSNA), International hip dysplasia recommend hip-healthy swaddling.

- Any physical limitation(LGA, oligohydramnios, twins) in utero can contribute to DDH. It also increases the risk of other abnormalities like Metatarsus adducts, congenital muscular torticollis, and congenital knee dislocation.

- Postmaturity is a risk factor. Prematurity is not associated with increased risk.[6]

Epidemiology

The incidence varies with age at diagnosis, race, and modality by which diagnosis was made. DDH has a spectrum that ranges from mild hip instability, which resolves spontaneously to dislocation, which needs surgery. In a prospective study by M Kokavec & Bialik V, the sonographic incidence is about 69.5 per 1000, but most of them self resolve in about 6 to 8 weeks, leaving 4.8 per 1000, which requires some form of treatment. No additional incidence was seen at age one.[7]

The incidence varies from 0.06 in Africans to 76.1 per 1000 in Native Americans due to the combination of genetics and swaddling.

Unilateral involvement in 63% and 64% involves the left side due to in utero most frequent fetal positioning (left occipitoanterior). The left hip of the fetus is adducted against the mother's lumbosacral spine.[8][9]

Pathophysiology

The formation of the hip joint is highly dependent on the dynamic relationship between femur and acetabulum. Any interference with proper contact between these two in utero or infancy leads to DDH.

Lower limb buds develop around four weeks, chondroblasts aggregate to form the future bones of the hip joint. At six weeks of life, cartilage develops into femur diaphysis, precartilage into the future femoral head, which can’t be differentiated from the acetabulum. Blastemal cells form trochanteric projection.

In the 7th week, Interzone differentiates the sides of the hip joint. Proximally acetabulum is formed as a shallow depression at 65 degrees; this later must deepen to 180 degrees, distally the femoral head and articular cartilage. The middle layer undergoes autolysis to form joint space, synovial membrane, and ligamentum teres. By 11th-week, the hip joint is recognizable. But in utero femoral head growth is faster than acetabulum, which results in under coverage of the femoral head, so any disturbance in the contact will lead to abnormal development.

Swaddling in extreme position (extended hip, adducted, immobile) resulting in maligned contact between the acetabulum and femur prevents proper development of the hip. Acetabulum continues to grow up to age 5.

Maligned contact for a prolonged period leads to chronic changes like hypertrophy of capsule, ligament teres, the formation of thickened acetabular edge (neolimbus), which further prevents the contact, and prevents the relocation of the femoral head.[10]

History and Physical

Clinical features vary for mild hip instability, limited abduction in the infant, asymmetric gait in the toddler, hip pain in adolescence, and osteoarthritis in the adult.

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons(AAOS), the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America(POSN), and the Canadian Task Force recommends screening newborn for DDH.

Newborn: Clinical examination is crucial in the identification of DDH, especially babies with risk factors. Hip instability/dislocation can be identified by Barlow and Ortolani manoeuver.

Ortolani maneuver: Infant in the supine position, hip flexed at 90 degrees and in neutral rotation. The infant should be calm, and clothes and diapers should be removed. This manoeuver reduces dislocated hip. The hip is held in the way the thumb on the inner aspect and index and ring finger on the greater trochanter. While applying anterior force on the greater trochanter, gently abduct the hip. If the hip dislocated, one would feel a jerk or clunk. "Hip clicks" are clinically insignificant without instability.[11]

Barlow maneuver: in the same above position, while applying posterior force to trochanter (AAP recommends against posterior force), adduct the hip. You will feel the clunk or jerk if the hip can be dislocated. This maneuver should be done gently as forceful adduction can cause instability.[12]

The sensitivity of this maneuver with experienced hands (ranging from 87 to 97 percent) and specificity varies from 98 to 99 %.[13]

Asymmetry in the position and or the number of the gluteal skin folds may be a clue for DDH. But asymmetry is a normal finding in 27 % of infants.

Galeazzi (Allis) sign identifies real or apparent of the femur, by comparing the knee height while hip and knee are flexed and feet flat on the table.

Beyond the neonatal period: Limited range of movement in the hip joint, could be a clue for diagnosis. Limited hip abduction (<75°) or adduction (30 degrees past midline).

The Klisic test: Place the middle finger over the greater trochanter and index finger over the anterior superior iliac spine.

- On the normal hip, an imaginary line between the two fingers points at or above the umbilicus.

- On a dislocated hip, the trochanter is elevated, and the line projects inferior to the umbilicus.

Asymmetrical gait (Trendelenburg gait) due to abductor insufficiency, Lumbar lordosis, toe walking, leg length discrepancies, and early hip osteoarthritis may indicate DDH.

Evaluation

The POSNA, the Canadian Task Force on DDH, and the AAOS, the American Academy of Pediatrics, recommends periodic surveillance for DDH throughout infancy. The reasonable screening goal is to prevent late presentation beyond six months.

The 2000 AAP clinical practice guideline recommended the hip ultrasound (US) at six weeks of age or Xray of the hip at four months of age in girls with a positive family history of DDH or breech presentation at third trimester. Universal screening is controversial, as most of the instability if found self resolves.[14]

Diagnosis depends on local resources and the availability of expert guidance.

Newborns

- Normal exam with risk factors - US hip at six weeks (allowing time for resolution of physiologic immaturity and laxity)

- Inconclusive exam or hip clicks - Repeat exam in 2 to 4 weeks.

- Positive Ortolani or Barlow - Refer to an orthopedic specialist with experience.

Four Weeks to 4 Months

- Inconclusive exam - Refer to a specialist or Hip US at six weeks.

- Positive Barlow or Ortolani - Refer to an orthopedic specialist with experience.

Beyond Four Months

- Clinical examination is limited as capsule laxity decreases; the Barlow and Ortolani maneuvers may not be positive. Limited hip abduction becomes the most crucial screening method in older children.

- Femoral head nuclei usually appear between 4 to 6 months (range 1.5 to 8 months), so X-ray is the preferred diagnostic tool over the hip US.

- Normal pelvic radiographs at four months can reliably exclude DDH in children with risk factors.

Imaging

The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine and the American college of radiology recommend the US of the hip.[15] It is used to visualize acetabular dysplasia, hip dislocation, femoral head anatomy, ligament teres, and hip capsule. The most important finding to know is femoral head coverage by acetabulum (minimum 50%) and depth of the bony acetabulum (Alpha angle: More than 60 degrees considered normal).

Criteria for DDH has been established for static imaging (Graf classification)

GRAF classification:

- Alpha angle-angle between bony acetabulum and Illium (Normal > 60 degrees)

- Beta angle-angle between labrum and ileum (Normal < 55 degrees)

Based on these angles, DDH is classified into four types.

X-ray: anteroposterior (AP) of the pelvis - lines of mensuration:

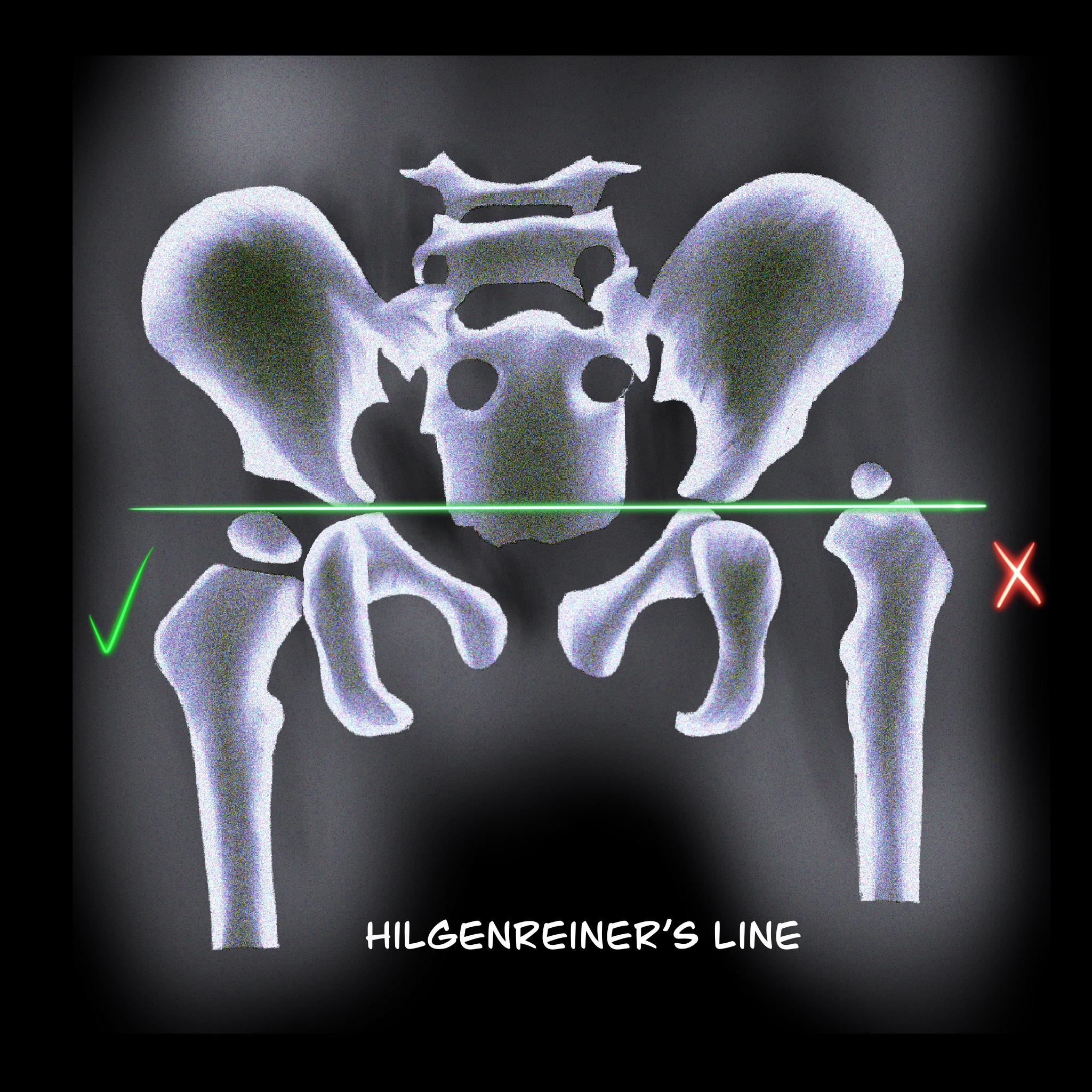

- Hilgenreiner's line: a horizontal line through the right and left triradiate cartilage, head of the femur should be inferior to this line. (Figure 1)

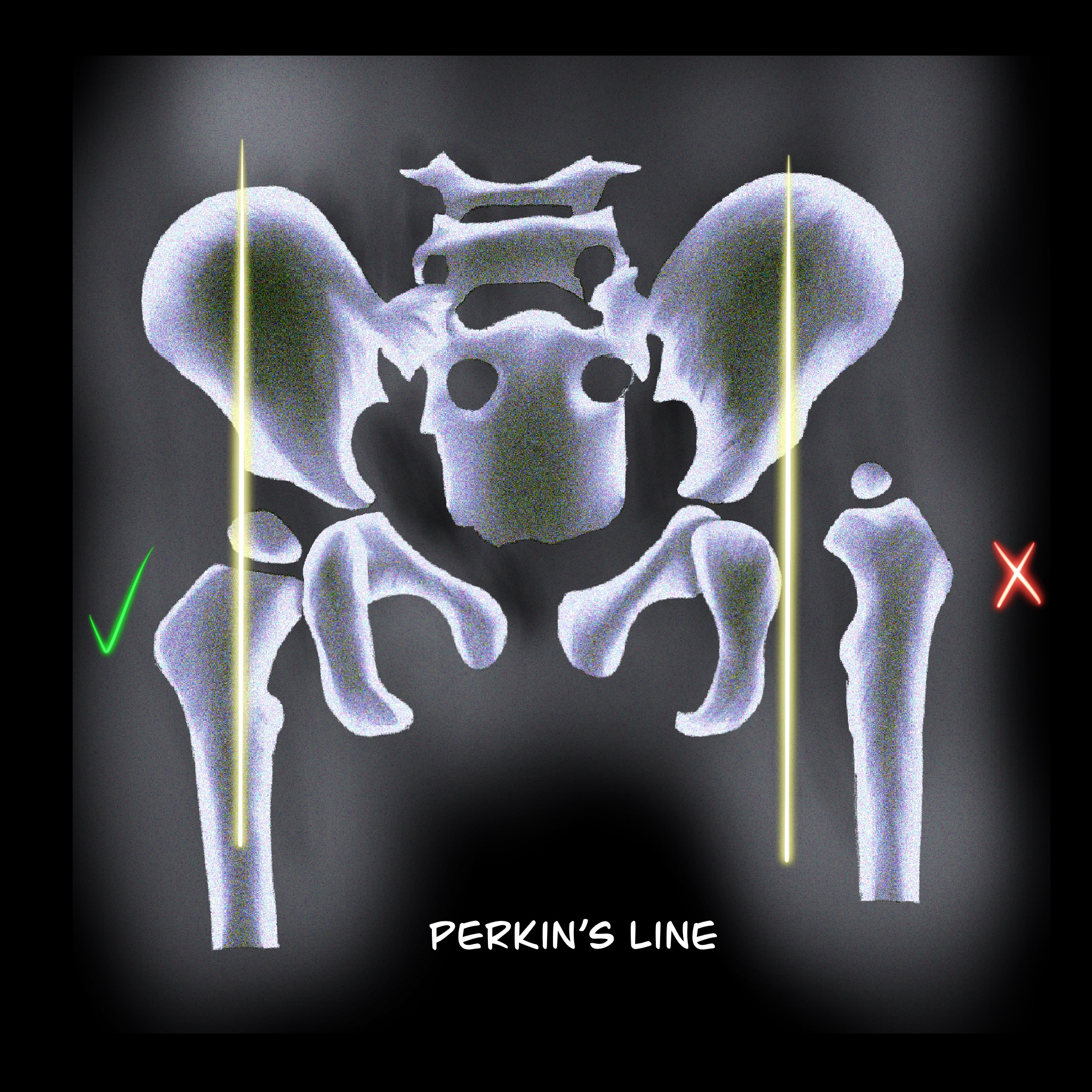

- Perkin's line: Perpendicular line to Hilgenreiner's line through a focus at the lateral side of the acetabulum. The femoral head should be medial to this line. (Figure 2)

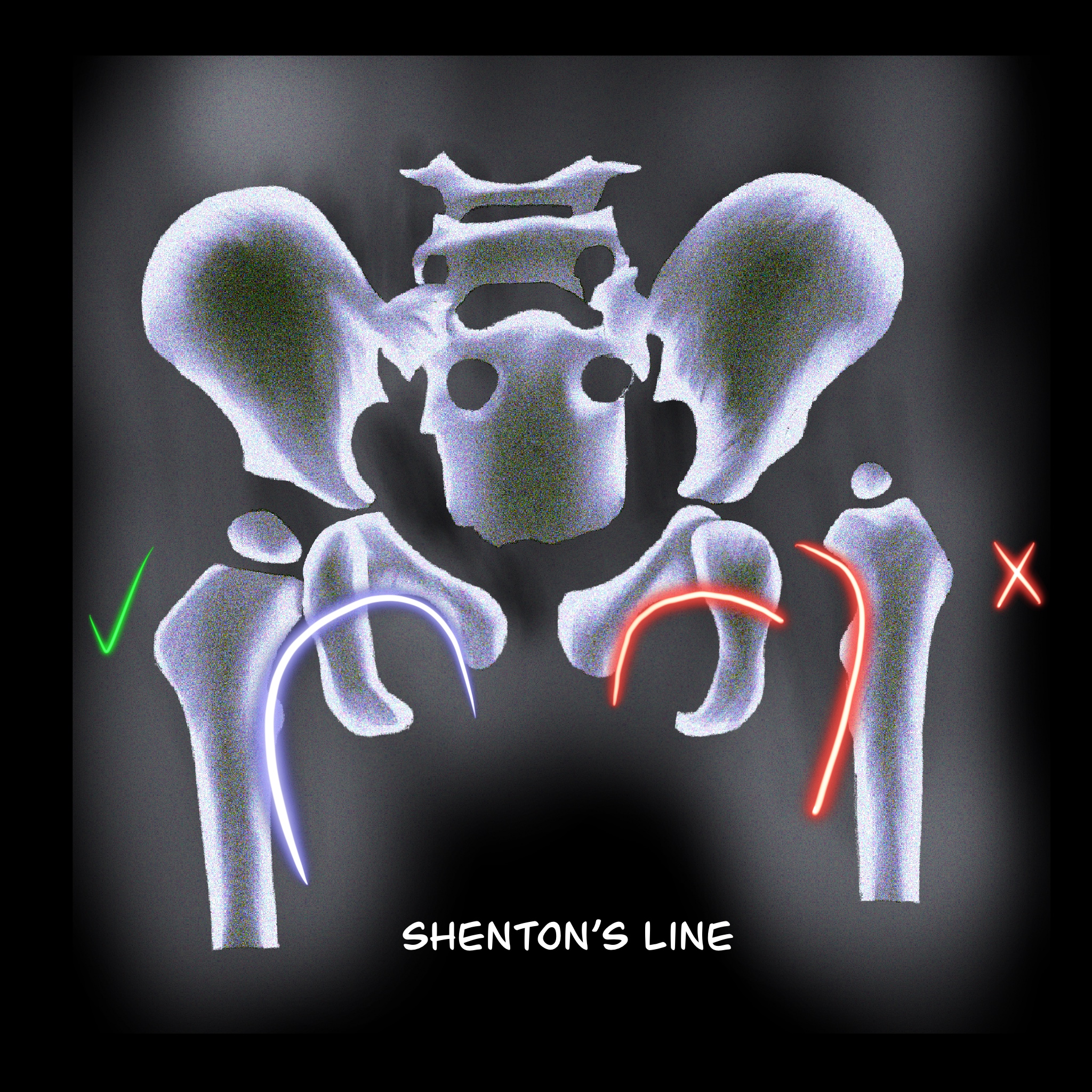

- Shenton's line: Smooth arc that connects the femoral neck to the superior margin of the obturator foramen. Any disruption indicates an abnormality. (Figure 3)

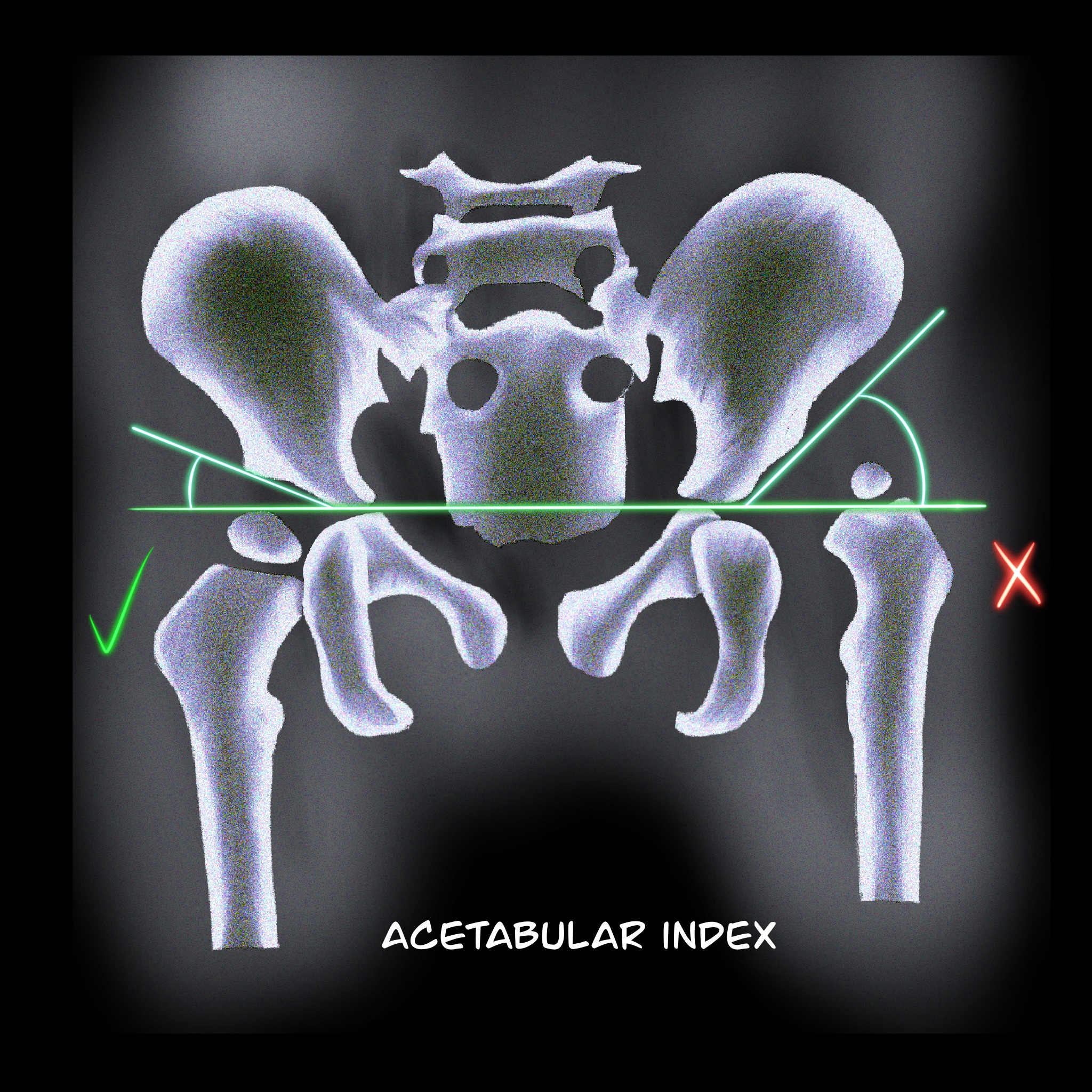

- Acetabular index: the intersection between Hilgenreiner's line and a line drawn tangential to the lateral ossific margin of the roof of the acetabulum. The normal index is less than <35 degrees at birth and <25 degrees at age one. (Figure 4)

- The center-edge angle of Wiberg: Formed by Perkin´s line and a line coming from the center of the femoral head to the lateral edge of the acetabulum. This measurement is reliable in patients older than 5 years old. Values should be > 20 degrees.

Treatment / Management

The goal is to provide an optimal environment for the growth of the femoral head and acetabulum. So a high index of suspicion and routine surveillance is needed to detect DDH and prevent complications.

To provide this optimal contact between the femoral head and acetabulum, various treatment modalities like abduction splinting, closed reduction, open reduction are available.

Double diapering is most likely harmless, but efficacy is close to zero.

0 to 4 Weeks

- Mild instability without a dislocatable hip can be watched.[16]

- Early referral to an orthopedic surgeon experienced treatment of DDH will be optimal if the hips are dislocatable. The application of abduction splints (Pavlik harness) will be up to the orthopedic surgeon who manages it. But a study done by Larson JE et al. concluded waiting up to 30 days before initiation of treatment shows no significant difference in the outcome.[17]

1 to 6 Months

Abduction devices like Pavlik harness, Von Rosen splint, Lausanne-developed abduction brace, Ilfeld orthosis, and Frejka pillow can be tried. Pavlik harness is the widely used device for DDH. It consists of an anterior strap that flexes the hip at 90 degrees and prevents extension, posterior strap to prevent adduction. Its worn 23 hours per day for at least six weeks or until the hip is stable. The US of the hip is done every 3- 4 weeks to monitor the position of the femoral head. The success rate is about 90 % for Barlow's positive hip.

The failure rate is high with the following conditions:[18] Ortolani positive hip, initiation of treatment after seven weeks, multigravida, foot deformity, and male sex.

If the hips are not reduced by three weeks, semi-rigid, non-flexible abduction devices like Ilfed orthosis to keep the hip in abducted position can be tried in a study by Sankar et al. 82 % success rate with Ilfed orthosis after Pavlik harness failure.[19]

6 to 18 Months

For infants who are diagnosed with DDH at this age or patients who failed with abduction devices, closed reduction with hip spica cast is preferred. Under general anesthesia (GA), the hip is placed in 90-100 degrees flexion and 40-50 degrees abduction. The failure rate is about 13.6 %.[20]

The main complication is avascular necrosis of the head. CT or MRI is needed to confirm the position of the hip position. In a study by Gornitzky AL et al., MRI with contrast can identify perfusion abnormalities following closed reduction, thus preventing AVN.[21]

18 Months to 8 Years

Open reduction is preferred for children diagnosed with DDH over 18 months and infants who failed closed reduction. Open reduction can be used to correct anatomical abnormalities like inverted labrum, neolimbus, pulvinar, hypertrophied ligamentum trees. Capsulorrhaphy and release of tight iliopsoas tendon can also be done. The two preferred approaches are anterior (Smith-Peterson) and medial. Medial is less invasive, but anterior is classical and will help correct most of the anatomical abnormalities. A femoral shortening osteotomy can be added to children if needed. The main complication is AVN. After open reduction, a spica cast applied and reduction is confirmed with CT or MRI.

Acetabular Dysplasia

Children with shallow or vertical acetabulum lead to osteoarthritis due to edge loading. Patients presenting with acetabular dysplasia up to age 5, without dislocation can be treated with part-time or full-time abduction orthosis.

After age 5, pelvic osteotomies (Salter, Pemberton, and Dega) use a single cut to increase anterior or anterolateral coverage. If the patient has an open triradiate cartilage center, triple cut (triple innominate osteotomy) can be performed.

Salvage pelvic osteotomies: Shelf procedure is indicated for patients >8 years old with a subluxated femoral head. By placing an extra-articular buttress of bone to the lateral weight-bearing aspect of the acetabulum. Chiari procedure is indicated for patients with inadequate femoral head coverage with a concentric reduction that cannot be obtained. It medializes the acetabulum via iliac osteotomy.

Adolescent/Adult Hip Preservation Surgery

Patients who are presenting with hip pain and with shallow acetabulum (radiographic femoral head undercoverage), and closed triradiate cartilage but without signs of hip degeneration can be treated with a periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). Bernese PAO is a technique in which multiple cuts are made to modify and reorient acetabular cartilage while maintaining an intact posterior column.[22]

Differential Diagnosis

Other conditions causing leg length discrepancies:

- Proximal femoral focal deficiency

- A femoral neck fracture

- Coxa vara

- Residual effects of infective arthritis

Prognosis

The long-term outcome of treated DDH is based on the degree of dysplasia, the age of diagnosis and type of treatment, and whether a concentrically reduced hip joint was obtained.

Approximately 90 percent of neonatal hips with instability or mild dysplasia (Barlow-positive with an alpha angle of 50 to 60 and with 50% to 60 % of coverage) resolve spontaneously with normal functional and radiographic outcomes.[5] A 95% reduction is achieved with Pavlik harness, and residual dysplasia occurs in 20%. If left untread over a prolonged period, there will be a gradual progression of functional disability and causes accelerated osteoarthritis.[23]

Complications

Failure to identify and treat DDH can lead to functional disability, Hip pain, and accelerated osteoarthritis.

Complications Following Pelvic Harness

- The most severe complication is Avascular necrosis of the femoral head, which varies from 0% to 5%.[24] This complication can be prevented by proper fit.

- Femoral nerve palsy: if the infant stops demonstrating spontaneous knee extension while in the Pavlik harness, suspect femoral nerve palsy. Incidence of about 2.5 %, most of them are associated with severe dysplasia or maintaining the hip flexion beyond 120 degrees. Femoral palsy resolves if the harness is removed.

- Residual hip dysplasia: follow up x-ray bi-annual or annual till skeletal maturity are needed to monitor this condition. A normal X-ray at age is two years of life indicates a good prognosis.

- Other complications include skin irritation and knee subluxation.

Complication following open or closed reduction: redislocation, osteonecrosis, infection, and stiffness.

Deterrence and Patient Education

One of the main postnatal risk factors for DDH is swaddling, so the parents must learn the proper swaddling technique to prevent DDH before leaving the hospital.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Developmental dysplasia of the hip management requires early identification from pediatricians, family physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and appropriate use of technology ultrasound vs. x-ray and referral to a specialist. American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons, and the Canadian Task Force provide clear guidelines for identifying and managing DDH.[25][13][14]

The treatment depends on the age of the patient and the degree of dysplasia. Minor hip instability (Barlow positive, Ortalani negative) spontaneously recovers in 90% of cases in the first two weeks of life.[8] Continued surveillance by the primary care provider during infancy improves detection and early referral. Pavlik harness corrects 95% of DDH if applied before six months. Residual dysplasia occurs even after appropriate treatment, so annual follow up is required until skeletal maturity.[26]

Without early treatment, the child may develop limp, leg length discrepancy, limited hip abduction, and in fact, DDH is the most common cause of early osteoarthritis in women under age 40.

Screening and identifying DDH before six months of age should be the goal to prevent long term complications.