[1]

Arnold M, Abnet CC, Neale RE, Vignat J, Giovannucci EL, McGlynn KA, Bray F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul:159(1):335-349.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.068. Epub 2020 Apr 2

[PubMed PMID: 32247694]

[2]

Correa P. The biological model of gastric carcinogenesis. IARC scientific publications. 2004:(157):301-10

[PubMed PMID: 15055303]

[3]

Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2006 Jul:19(3):449-90

[PubMed PMID: 16847081]

[4]

Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Park B, Nam BH. Helicobacter pylori Therapy for the Prevention of Metachronous Gastric Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Mar 22:378(12):1085-1095. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708423. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29562147]

[5]

Testerman TL, Morris J. Beyond the stomach: an updated view of Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Sep 28:20(36):12781-808. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.12781. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25278678]

[6]

Pittman ME, Voltaggio L, Bhaijee F, Robertson SA, Montgomery EA. Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis: Recognizing Precursor Lesions for Appropriate Patient Evaluation. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015 Dec:39(12):1611-20. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000481. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26291507]

[7]

Toh BH. Diagnosis and classification of autoimmune gastritis. Autoimmunity reviews. 2014 Apr-May:13(4-5):459-62. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.048. Epub 2014 Jan 11

[PubMed PMID: 24424193]

[8]

Annibale B, Esposito G, Lahner E. A current clinical overview of atrophic gastritis. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2020 Feb:14(2):93-102. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1718491. Epub 2020 Jan 24

[PubMed PMID: 31951768]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[9]

Weck MN, Stegmaier C, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Epidemiology of chronic atrophic gastritis: population-based study among 9444 older adults from Germany. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2007 Sep 15:26(6):879-87

[PubMed PMID: 17767472]

[10]

Banks M, Graham D, Jansen M, Gotoda T, Coda S, di Pietro M, Uedo N, Bhandari P, Pritchard DM, Kuipers EJ, Rodriguez-Justo M, Novelli MR, Ragunath K, Shepherd N, Dinis-Ribeiro M. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients at risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2019 Sep:68(9):1545-1575. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318126. Epub 2019 Jul 5

[PubMed PMID: 31278206]

[11]

Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, Genta RM. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis--pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2013 Sep:10(9):529-41. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.101. Epub 2013 Jun 18

[PubMed PMID: 23774773]

[12]

Namekata T, Miki K, Kimmey M, Fritsche T, Hughes D, Moore D, Suzuki K. Chronic atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection among Japanese Americans in Seattle. American journal of epidemiology. 2000 Apr 15:151(8):820-30

[PubMed PMID: 10965979]

[13]

Spence AD, Cardwell CR, McMenamin ÚC, Hicks BM, Johnston BT, Murray LJ, Coleman HG. Adenocarcinoma risk in gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia: a systematic review. BMC gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 11:17(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0708-4. Epub 2017 Dec 11

[PubMed PMID: 29228909]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[14]

Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Niikura R, Hayakawa Y, Yamada A, Ushiku T, Fukayama M, Koike K. Histologic intestinal metaplasia and endoscopic atrophy are predictors of gastric cancer development after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016 Oct:84(4):618-24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.791. Epub 2016 Mar 16

[PubMed PMID: 26995689]

[15]

Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2001 Sep 13:345(11):784-9

[PubMed PMID: 11556297]

[16]

Wroblewski LE, Peek RM Jr, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2010 Oct:23(4):713-39. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-10. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20930071]

[17]

Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, Garrido M, Kikuste I, Megraud F, Matysiak-Budnik T, Annibale B, Dumonceau JM, Barros R, Fléjou JF, Carneiro F, van Hooft JE, Kuipers EJ, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019 Apr:51(4):365-388. doi: 10.1055/a-0859-1883. Epub 2019 Mar 6

[PubMed PMID: 30841008]

[18]

Cavalcoli F, Zilli A, Conte D, Massironi S. Micronutrient deficiencies in patients with chronic atrophic autoimmune gastritis: A review. World journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jan 28:23(4):563-572. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i4.563. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28216963]

[19]

Vannella L, Lahner E, Osborn J, Annibale B. Systematic review: gastric cancer incidence in pernicious anaemia. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2013 Feb:37(4):375-82. doi: 10.1111/apt.12177. Epub 2012 Dec 10

[PubMed PMID: 23216458]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[20]

Kato Y, Kitagawa T, Yanagisawa A, Kubo K, Utsude T, Hiratsuka H, Tamaki M, Sugano H. Site-dependent development of complete and incomplete intestinal metaplasia types in the human stomach. Japanese journal of cancer research : Gann. 1992 Feb:83(2):178-83

[PubMed PMID: 1372886]

[21]

Morson BC, Sobin LH, Grundmann E, Johansen A, Nagayo T, Serck-Hanssen A. Precancerous conditions and epithelial dysplasia in the stomach. Journal of clinical pathology. 1980 Aug:33(8):711-21

[PubMed PMID: 7430384]

[22]

Uedo N, Yao K. Endoluminal Diagnosis of Early Gastric Cancer and Its Precursors: Bridging the Gap Between Endoscopy and Pathology. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2016:908():293-316. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41388-4_14. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27573777]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[23]

Sugimoto M, Ban H, Ichikawa H, Sahara S, Otsuka T, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Furuta T, Andoh A. Efficacy of the Kyoto Classification of Gastritis in Identifying Patients at High Risk for Gastric Cancer. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2017:56(6):579-586. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7775. Epub 2017 Mar 17

[PubMed PMID: 28321054]

[24]

Nagata N, Shimbo T, Akiyama J, Nakashima R, Kim HH, Yoshida T, Hoshimoto K, Uemura N. Predictability of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia by Mottled Patchy Erythema Seen on Endoscopy. Gastroenterology research. 2011 Oct:4(5):203-209

[PubMed PMID: 27957016]

[25]

Uedo N, Ishihara R, Iishi H, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S, Yamada T, Imanaka K, Takeuchi Y, Higashino K, Ishiguro S, Tatsuta M. A new method of diagnosing gastric intestinal metaplasia: narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2006 Aug:38(8):819-24

[PubMed PMID: 17001572]

[26]

Crafa P, Russo M, Miraglia C, Barchi A, Moccia F, Nouvenne A, Leandro G, Meschi T, De' Angelis GL, Di Mario F. From Sidney to OLGA: an overview of atrophic gastritis. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2018 Dec 17:89(8-S):93-99. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i8-S.7946. Epub 2018 Dec 17

[PubMed PMID: 30561425]

[27]

Li Y, Xia R, Zhang B, Li C. Chronic Atrophic Gastritis: A Review. Journal of environmental pathology, toxicology and oncology : official organ of the International Society for Environmental Toxicology and Cancer. 2018:37(3):241-259. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2018026839. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30317974]

[28]

White JR, Winter JA, Robinson K. Differential inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection: etiology and clinical outcomes. Journal of inflammation research. 2015:8():137-47. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S64888. Epub 2015 Aug 13

[PubMed PMID: 26316793]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[29]

Park JY, Cornish TC, Lam-Himlin D, Shi C, Montgomery E. Gastric lesions in patients with autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG) in a tertiary care setting. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2010 Nov:34(11):1591-8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f623af. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20975338]

[30]

Oo TH, Rojas-Hernandez CM. Challenging clinical presentations of pernicious anemia. Discovery medicine. 2017 Sep:24(131):107-115

[PubMed PMID: 28972879]

[31]

Zagari RM, Rabitti S, Greenwood DC, Eusebi LH, Vestito A, Bazzoli F. Systematic review with meta-analysis: diagnostic performance of the combination of pepsinogen, gastrin-17 and anti-Helicobacter pylori antibodies serum assays for the diagnosis of atrophic gastritis. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2017 Oct:46(7):657-667. doi: 10.1111/apt.14248. Epub 2017 Aug 7

[PubMed PMID: 28782119]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[32]

Terasawa T, Nishida H, Kato K, Miyashiro I, Yoshikawa T, Takaku R, Hamashima C. Prediction of gastric cancer development by serum pepsinogen test and Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in Eastern Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014:9(10):e109783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109783. Epub 2014 Oct 14

[PubMed PMID: 25314140]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[33]

Hwang YJ, Kim N, Lee HS, Lee JB, Choi YJ, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH. Reversibility of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia after Helicobacter pylori eradication - a prospective study for up to 10 years. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2018 Feb:47(3):380-390. doi: 10.1111/apt.14424. Epub 2017 Nov 29

[PubMed PMID: 29193217]

[34]

Zhao Z, Yin Z, Wang S, Wang J, Bai B, Qiu Z, Zhao Q. Meta-analysis: The diagnostic efficacy of chromoendoscopy for early gastric cancer and premalignant gastric lesions. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2016 Sep:31(9):1539-45. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13313. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26860924]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[35]

Anagnostopoulos GK, Yao K, Kaye P, Fogden E, Fortun P, Shonde A, Foley S, Sunil S, Atherton JJ, Hawkey C, Ragunath K. High-resolution magnification endoscopy can reliably identify normal gastric mucosa, Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis, and gastric atrophy. Endoscopy. 2007 Mar:39(3):202-7

[PubMed PMID: 17273960]

[36]

Ang TL, Pittayanon R, Lau JY, Rerknimitr R, Ho SH, Singh R, Kwek AB, Ang DS, Chiu PW, Luk S, Goh KL, Ong JP, Tan JY, Teo EK, Fock KM. A multicenter randomized comparison between high-definition white light endoscopy and narrow band imaging for detection of gastric lesions. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2015 Dec:27(12):1473-8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000478. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26426836]

[37]

Ezoe Y, Muto M, Uedo N, Doyama H, Yao K, Oda I, Kaneko K, Kawahara Y, Yokoi C, Sugiura Y, Ishikawa H, Takeuchi Y, Kaneko Y, Saito Y. Magnifying narrowband imaging is more accurate than conventional white-light imaging in diagnosis of gastric mucosal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011 Dec:141(6):2017-2025.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.007. Epub 2011 Aug 19

[PubMed PMID: 21856268]

[38]

Isajevs S, Liepniece-Karele I, Janciauskas D, Moisejevs G, Funka K, Kikuste I, Vanags A, Tolmanis I, Leja M. The effect of incisura angularis biopsy sampling on the assessment of gastritis stage. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014 May:26(5):510-3. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000082. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24625520]

[39]

Varbanova M, Wex T, Jechorek D, Röhl FW, Langner C, Selgrad M, Malfertheiner P. Impact of the angulus biopsy for the detection of gastric preneoplastic conditions and gastric cancer risk assessment. Journal of clinical pathology. 2016 Jan:69(1):19-25. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-202858. Epub 2015 Jul 10

[PubMed PMID: 26163538]

[40]

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans JA, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Fisher DA, Foley K, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Lightdale JR, Pasha SF, Sharaf R, Shergill AK, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in the management of premalignant and malignant conditions of the stomach. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2015 Jul:82(1):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1967. Epub 2015 Apr 29

[PubMed PMID: 25935705]

[41]

Matysiak-Budnik T, Camargo MC, Piazuelo MB, Leja M. Recent Guidelines on the Management of Patients with Gastric Atrophy: Common Points and Controversies. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2020 Jul:65(7):1899-1903. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06272-9. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32356261]

[42]

Isajevs S, Liepniece-Karele I, Janciauskas D, Moisejevs G, Putnins V, Funka K, Kikuste I, Vanags A, Tolmanis I, Leja M. Gastritis staging: interobserver agreement by applying OLGA and OLGIM systems. Virchows Archiv : an international journal of pathology. 2014 Apr:464(4):403-7. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1544-3. Epub 2014 Jan 30

[PubMed PMID: 24477629]

[43]

Kong YJ, Yi HG, Dai JC, Wei MX. Histological changes of gastric mucosa after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 May 21:20(19):5903-11. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5903. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24914352]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[44]

Chen HN, Wang Z, Li X, Zhou ZG. Helicobacter pylori eradication cannot reduce the risk of gastric cancer in patients with intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia: evidence from a meta-analysis. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2016 Jan:19(1):166-75. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0462-7. Epub 2015 Jan 22

[PubMed PMID: 25609452]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[45]

Rokkas T, Rokka A, Portincasa P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the role of Helicobacter pylori eradication in preventing gastric cancer. Annals of gastroenterology. 2017:30(4):414-423. doi: 10.20524/aog.2017.0144. Epub 2017 Apr 7

[PubMed PMID: 28655977]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[46]

Wong BC, Zhang L, Ma JL, Pan KF, Li JY, Shen L, Liu WD, Feng GS, Zhang XD, Li J, Lu AP, Xia HH, Lam S, You WC. Effects of selective COX-2 inhibitor and Helicobacter pylori eradication on precancerous gastric lesions. Gut. 2012 Jun:61(6):812-8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300154. Epub 2011 Sep 13

[PubMed PMID: 21917649]

[47]

Huang XZ, Chen Y, Wu J, Zhang X, Wu CC, Zhang CY, Sun SS, Chen WJ. Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs use reduce gastric cancer risk: A dose-response meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017 Jan 17:8(3):4781-4795. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13591. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27902474]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[48]

Tang XD, Zhou LY, Zhang ST, Xu YQ, Cui QC, Li L, Lu JJ, Li P, Lu F, Wang FY, Wang P, Bian LQ, Bian ZX. Randomized double-blind clinical trial of Moluodan () for the treatment of chronic atrophic gastritis with dysplasia. Chinese journal of integrative medicine. 2016 Jan:22(1):9-18. doi: 10.1007/s11655-015-2114-5. Epub 2015 Oct 1

[PubMed PMID: 26424292]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[49]

Han X, Jiang K, Wang B, Zhou L, Chen X, Li S. Effect of Rebamipide on the Premalignant Progression of Chronic Gastritis: A Randomized Controlled Study. Clinical drug investigation. 2015 Oct:35(10):665-73. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0329-z. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26369655]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[50]

Kong P, Cai Q, Geng Q, Wang J, Lan Y, Zhan Y, Xu D. Vitamin intake reduce the risk of gastric cancer: meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized and observational studies. PloS one. 2014:9(12):e116060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116060. Epub 2014 Dec 30

[PubMed PMID: 25549091]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[51]

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2017 Jan:20(1):1-19. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0622-4. Epub 2016 Jun 24

[PubMed PMID: 27342689]

[52]

Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, Taniguchi H, Fujisaki J, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2009:12(3):148-52. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0515-x. Epub 2009 Nov 5

[PubMed PMID: 19890694]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[53]

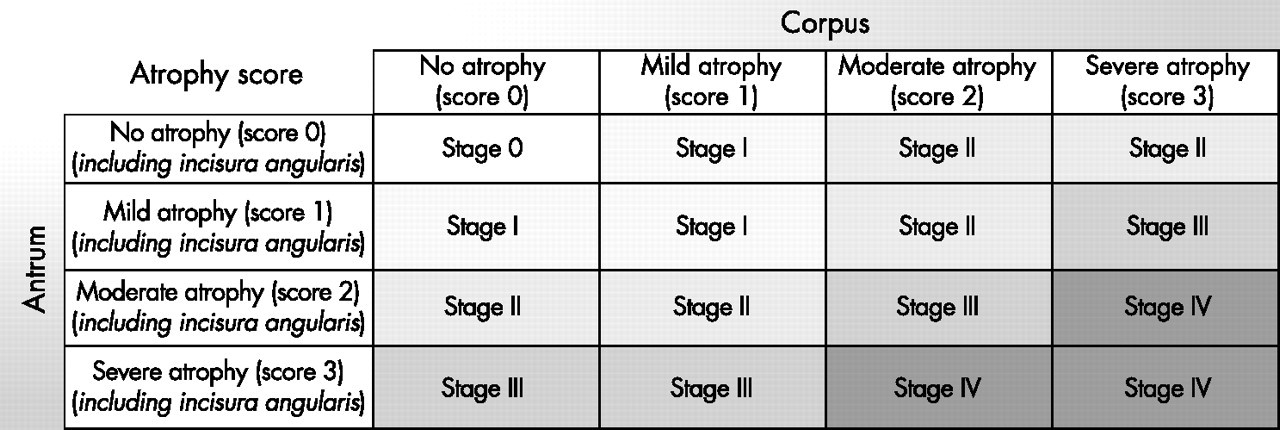

Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, Graham DY. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007 May:56(5):631-6

[PubMed PMID: 17142647]

[54]

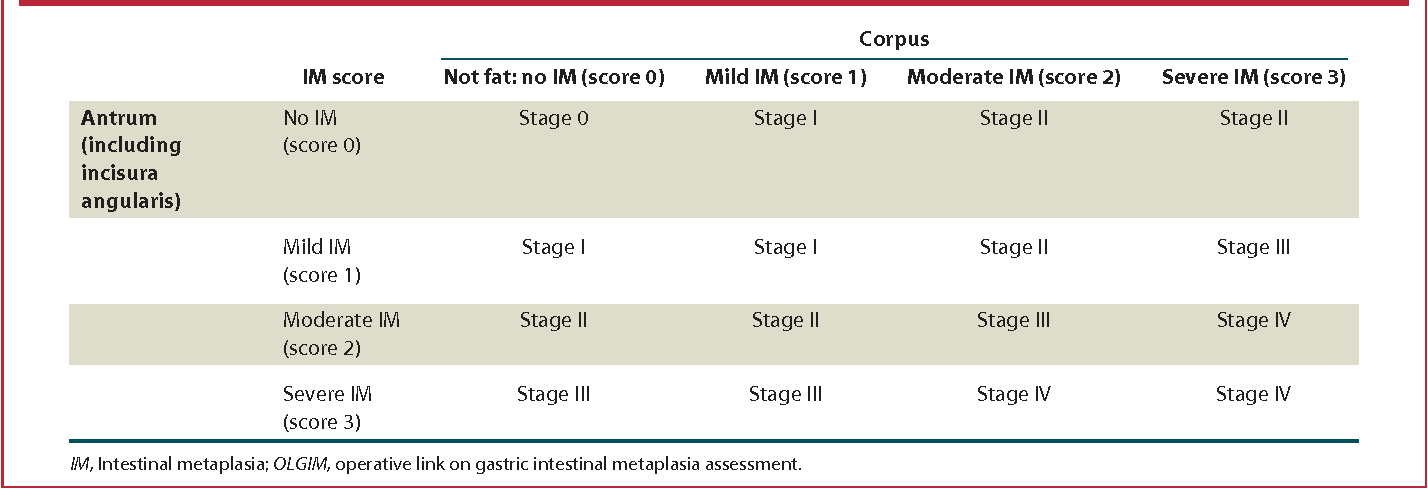

Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Haringsma J, Ter Borg F, de Vries RA, Bruno MJ, van Dekken H, Meijer J, van Grieken NC, Kuipers EJ. The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010 Jun:71(7):1150-8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.029. Epub 2010 Apr 9

[PubMed PMID: 20381801]

[55]

Mera RM, Bravo LE, Camargo MC, Bravo JC, Delgado AG, Romero-Gallo J, Yepez MC, Realpe JL, Schneider BG, Morgan DR, Peek RM Jr, Correa P, Wilson KT, Piazuelo MB. Dynamics of Helicobacter pylori infection as a determinant of progression of gastric precancerous lesions: 16-year follow-up of an eradication trial. Gut. 2018 Jul:67(7):1239-1246. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311685. Epub 2017 Jun 24

[PubMed PMID: 28647684]

[56]

Yue H, Shan L, Bin L. The significance of OLGA and OLGIM staging systems in the risk assessment of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2018 Jul:21(4):579-587. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0812-3. Epub 2018 Feb 19

[PubMed PMID: 29460004]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[57]

Correa P. Clinical implications of recent developments in gastric cancer pathology and epidemiology. Seminars in oncology. 1985 Mar:12(1):2-10

[PubMed PMID: 3975643]

[58]

LAUREN P. THE TWO HISTOLOGICAL MAIN TYPES OF GASTRIC CARCINOMA: DIFFUSE AND SO-CALLED INTESTINAL-TYPE CARCINOMA. AN ATTEMPT AT A HISTO-CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION. Acta pathologica et microbiologica Scandinavica. 1965:64():31-49

[PubMed PMID: 14320675]

[59]

Choi CE, Sonnenberg A, Turner K, Genta RM. High Prevalence of Gastric Preneoplastic Lesions in East Asians and Hispanics in the USA. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2015 Jul:60(7):2070-6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3591-2. Epub 2015 Feb 28

[PubMed PMID: 25724165]

[60]

González CA, Sanz-Anquela JM, Gisbert JP, Correa P. Utility of subtyping intestinal metaplasia as marker of gastric cancer risk. A review of the evidence. International journal of cancer. 2013 Sep 1:133(5):1023-32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28003. Epub 2013 Feb 5

[PubMed PMID: 23280711]

[61]

Conchillo JM, Houben G, de Bruïne A, Stockbrügger R. Is type III intestinal metaplasia an obligatory precancerous lesion in intestinal-type gastric carcinoma? European journal of cancer prevention : the official journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP). 2001 Aug:10(4):307-12

[PubMed PMID: 11535872]

[62]

Lahner E, Zagari RM, Zullo A, Di Sabatino A, Meggio A, Cesaro P, Lenti MV, Annibale B, Corazza GR. Chronic atrophic gastritis: Natural history, diagnosis and therapeutic management. A position paper by the Italian Society of Hospital Gastroenterologists and Digestive Endoscopists [AIGO], the Italian Society of Digestive Endoscopy [SIED], the Italian Society of Gastroenterology [SIGE], and the Italian Society of Internal Medicine [SIMI]. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2019 Dec:51(12):1621-1632. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.09.016. Epub 2019 Oct 19

[PubMed PMID: 31635944]