Introduction

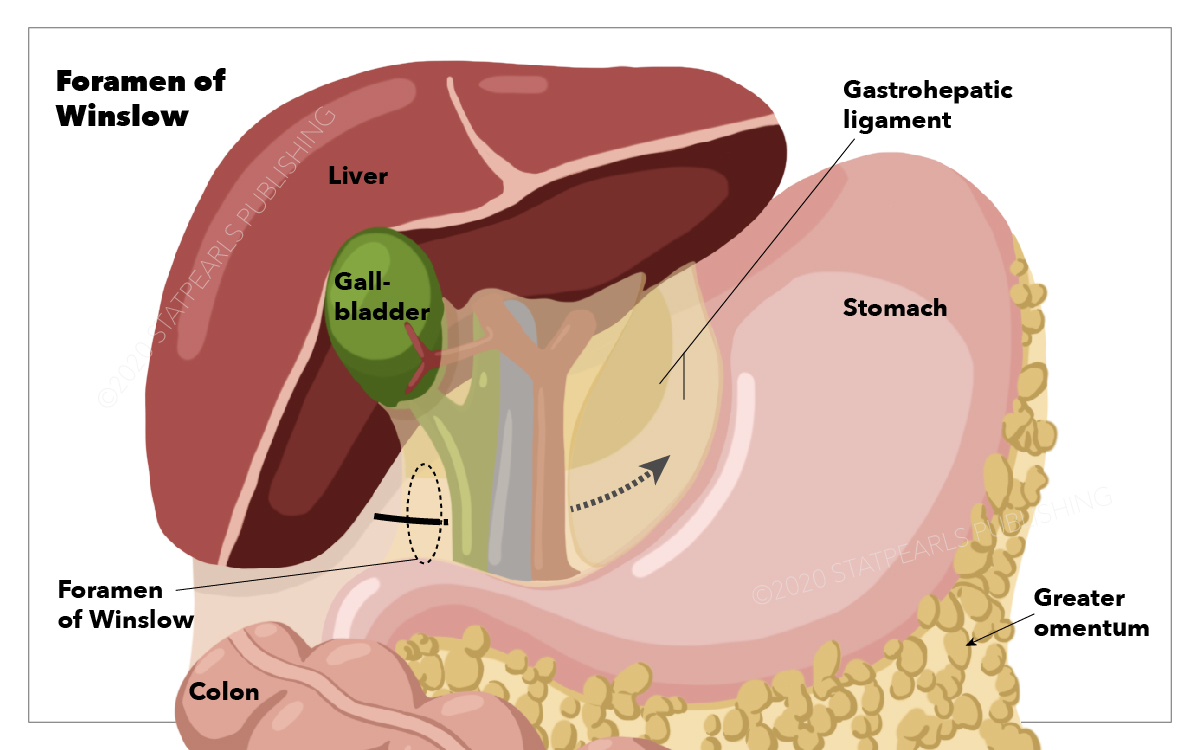

The foramen of Winslow is an oddity for the anatomist. The foramen of Winslow is defined superiorly by the caudate lobe of the liver and dorsally by the inferior vena cava. The inferior portion is defined by the duodenum, with the hepatoduodenal ligament serving as the ventral border. The foramen of Winslow is the only natural communication between the greater peritoneal cavity and the lesser sac. Also known as the epiploic foramen or the omental foramen, this small window was described by Jacob Winslow in his 1732 publication, Exposition anatomique de la structure du corps human (see Image. Foramen of Winslow).

Born in Denmark, Winslow converted to Catholicism and became a naturalized French citizen. Along with William Cheselden in London and Alexander Monro in Edinburgh, Winslow is considered among the preeminent anatomists of his day. His publication is considered unique in that it was based entirely on his objective observations and did not rely on the opinions of other anatomists. He eventually became a professor of anatomy at the prestigious Jardin du Roi in Paris. Furthermore, he was the first to describe the foramen spinosum at the base of the skull.[1][2]

Embryology

The embryonic foregut is suspended from the abdominal wall by ventral and dorsal mesentery. The liver forms within the ventral mesentery. The portion of the ventral mesentery between the liver and abdominal wall persists in the mature fetus as the falciform ligament, and the portion of ventral mesentery between the stomach and liver persists in the mature fetus as the lesser omentum. The lesser omentum includes the hepatogastric and hepatoduodenal ligaments. That portion of dorsal mesentery attached to the stomach persists in the mature fetus as the greater omentum. With the first 90 degrees of intestinal rotation, the stomach lies on its right side, bringing with it the lesser omentum. Thus, the right side of the stomach and the lesser omentum lie against the posterior abdominal wall but do not fuse with it. The space posterior to the stomach becomes the lesser sac. The midgut then rotates counterclockwise an additional 180 degrees, pivoting around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery. The third portion of the duodenum is draped transversely across the peritoneal cavity, from right to left, posterior to the superior mesenteric artery. This portion of the duodenum and the pancreas becomes secondarily retroperitoneal and forms the posterior wall of the lesser sac. The transverse colon is similarly draped transversely across the peritoneal cavity but lies anterior to the superior mesenteric artery. The greater omentum then becomes attached to the transverse colon, and the separation of the lesser sac from the greater peritoneal cavity becomes complete except for the small window at the free distal margin of the hepatoduodenal ligament, the foramen of Winslow.

Surgical Considerations

While locating the foramen of Winslow and viable tissue in the operating room is quite simple, finding it in stiff, nonpliable fixed tissue in the dissecting laboratory can be difficult. To find the foramen of Winslow, a clinician can begin at the hepatogastric ligament and follow the lesser curvature of the stomach distally to the pylorus, at which point the lesser omentum is known as the hepatoduodenal ligament. Following the duodenum distally until the termination of the hepatoduodenal ligament, a finger can be slipped around the edge of the hepatoduodenal ligament and into the foramen of Winslow. The cystic duct can then be followed to its junction with the common hepatic duct, which follows the course of the common bile duct within the hepatoduodenal ligament, leading to the foramen of Winslow. When the hepatic flexure of the colon is taken down, the second portion of the duodenum can be followed proximally until the first portion of the duodenum is reached, which is the inferior wall of the foramen of Winslow.[3][4]

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of Winslow’s foramen is 2-fold. First, it serves as a site for an internal hernia. Hernias in the foramen of Winslow are exceedingly uncommon. As with most internal hernias, the presenting symptoms are nonspecific and are generally those of intermittent bowel obstruction. Before the advent of modern imaging techniques, the diagnosis was frequently made only at laparotomy, and the delay in diagnosis led to significant mortality. CT scans now help with the diagnosis, and treatment consists of reduction of the hernia, with or without resection, depending on the viability of the herniated viscera. Laparoscopic repair has been described as well.

More importantly, because the hepatic artery and portal vein, as well as the common bile duct, pass through the hepatoduodenal ligament immediately adjacent to the foramen of Winslow, rapid access to the blood supply to the liver can be obtained in the event of uncontrolled hepatic bleeding. With the forefinger inserted through the foramen, the vessels can be pinched off between thumb and finger. For more stability, one jaw of a vascular clamp can be inserted into the foramen, allowing for clamping off the hepatic artery and portal vein. Both of these techniques are variations of what is commonly called the "Pringle maneuver," first described by surgeon James Hogarth Pringle in 1908. Pringle was born in Australia and of Scottish descent. His father was a famous surgeon and a contemporary of Joseph Lister. James Pringle emigrated to Scotland to attend medical school at the University of Edinburg and eventually was appointed surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Glasgow in 1896. He was well known for his expertise in the treatment of fractures and other injuries and radical amputations even before his 1908 publication of Notes on the Arrest of Hepatic Hemorrhage due to Trauma. He was known as a pioneer in trauma surgery.

Other Issues

The foramen of Winslow is an oddity for the anatomist, a phenomenon easily explained and easily understood by the embryologist, a source of rare consternation and occasional great relief to the surgeon, and for the student in the dissection lab, a treasure to be found at the end of what can be a long and frustrating search.