Introduction

The duodenum is the initial C-shaped segment of the small intestine and is a continuation of the pylorus. Distally, it is in continuation with the jejunum and ileum, with the proximal segment being the shortest and widest. Positioned inferiorly to the stomach, the duodenum is approximately 25 to 30 cm long. Interestingly enough, this portion of the small intestine got its name due to its length. In Latin, the term "duodenum" means 12 fingers, which is roughly the length of the duodenum. The 4 segments of the duodenum include the following:

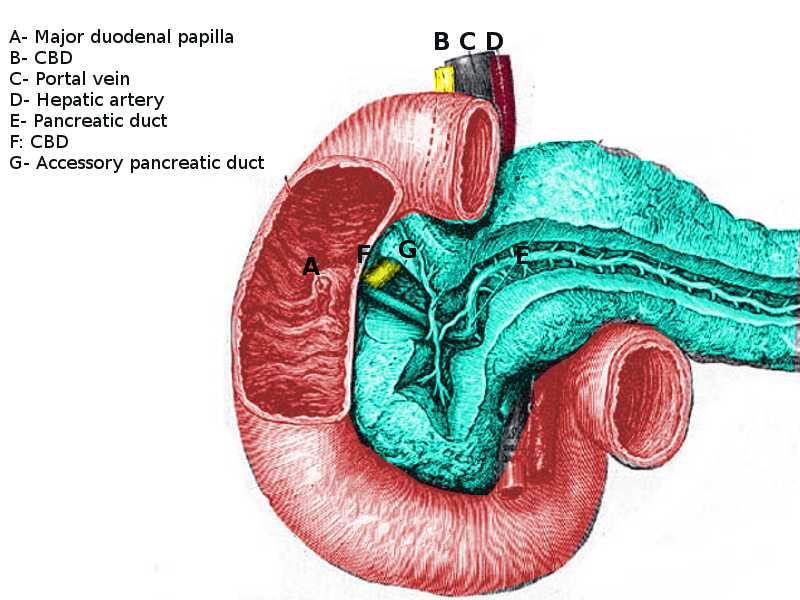

- The duodenal bulb, which connects to the undersurface of the liver via the hepatoduodenal ligament, which contains the portal vein, the hepatic artery, and common bile duct.

- The second or descending segment is just above the inferior vena cava and right kidney, with the head of the pancreas lying in a C-shaped concavity.

- The third segment runs from right to left in front of the aorta and inferior vena cava, with the superior mesenteric vessels in front of it.

- The fourth segment continues as the jejunum.

The walls of the duodenum are made up of 4 layers of tissue that are identical to the other layers of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. From innermost to the outermost layer, these are the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa layers. The mucosal layer lines the inner surface of the duodenum and is made of simple columnar cells with microvilli and numerous mucous glands. The submucosal layer is mostly a layer of connective tissue where blood vessels and nerves travel through. The muscularis layer contains the smooth muscle of the duodenum and allow mixing and forward peristaltic movement of chyme. The serosal layer is characterized by squamous epithelium that acts as a barrier for the duodenum from other organs within the human body.[1][2]

Structure and Function

The function of the duodenum is a continuation of the digestion process that initially began in the stomach. It receives chyme generated by the stomach through a controlled valve between the stomach and the duodenum called the pylorus. The digestion inside of the duodenum is facilitated by the digestive enzymes and intestinal juices secreted by the intestinal wall as well as fluids received from the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas. This is received into the duodenum by the major and minor papilla in the second part of the duodenum. The duodenal papilla is surrounded by a semicircular fold superiorly and the sphincter of Oddi which is the muscle that prevents reflux of duodenal secretions into the bile and pancreatic ducts.[3][4]

The duodenum also has the unique ability to regulate its environment with hormones that are released from the duodenal epithelium. One of those hormones is secretin, which is released when the pH of the duodenum decreases to a less than desirable level. This hormone acts to neutralize the pH of the duodenum by stimulating water and bicarbonate secretion into the duodenum. This aids in the digestion process as pancreatic amylase and lipase require a certain pH to function optimally. Another hormone that is released by the duodenal epithelium is cholecystokinin. Cholecystokinin is released in the presence of fatty acids and amino acids inside of the duodenum and acts to inhibit gastric emptying and also to stimulate contraction of the gallbladder while simultaneously causing relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi to allow delivery of bile into the duodenum to aid in digestion and absorption of nutrients.

Embryology

During embryological development of the gut, the duodenum is manifested in close association with other intestinal organogenesis processes. Craniocaudal and lateral folding cause the opening of the gut tube to the yolk sac to draw closed forming a pocket toward the superior end of the embryo, which will ultimately become the foregut. The duodenum arises from the caudal-most part of the foregut. However, it is hypothesized that the duodenum does not undergo any rotation but instead takes on its C-shape appearance due to the extension of the stomach toward the left and the relative fixation by the growing liver and pancreas. It is due to this process that the inferior portion of the duodenum becomes situated underneath the superior mesenteric artery. At the end of development, the duodenum loop lies to the right of the abdominal wall, and its peritoneal layers become incorporated into the peritoneal layer that lines the abdominal cavity. This process is the reason why the duodenum is sometimes described as being secondarily retroperitoneal.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply of the C-shaped duodenum is shared with the head of the pancreas. The proximal segment of the duodenum is supplied by the gastroduodenal artery and its branches which include the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. The distal segment of the duodenum is supplied by the superior mesenteric artery and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. The venous drainage follows the arteries and ultimately drains into the portal system. The duodenum also has lymphatic vessels which drain into the pancreaticoduodenal lymph nodes located along the pancreaticoduodenal vessels and the superior mesenteric lymph nodes.

Nerves

The nerves of the duodenum travel throughout the submucosal layer of the duodenum. The duodenum is richly innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system which includes branches of the anterior and posterior vagus trunks. These parasympathetic nerves pass through the celiac plexuses and follow the celiac trunk toward the duodenum. The nerves then synapse in ganglia in the gut plexuses in the duodenum and reach their final targets through short postsynaptic fibers. The sympathetic nerves are branches of the celiac plexus which originate from T5 through T9. These sympathetic nerves pass through the sympathetic chain and travel through the greater splanchnic nerve and synapse in the celiac ganglia. The postsynaptic sympathetic follow the branches of the celiac trunk toward the duodenum.

Muscles

The muscles located in the muscularis layer of the duodenum include the circular and longitudinal muscles. It is through the coordination of contraction of these muscles that allow for peristalsis to occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract, including the duodenum.

Surgical Considerations

The duodenojejunal flexure is the sudden turn which is usually identified during surgery by the location of the inferior mesenteric vein, which is located to the immediate left. The duodenojejunal flexure is attached to the posterior abdominal wall by the ligament of Treitz. Except for the first segment, the rest of the duodenum is retroperitoneal and has no mesentery and is fixed to the posterior abdominal cavity.

The distal end of the common bile duct joins with the pancreatic duct to form the biliopancreatic ampulla which opens on the dome of the major duodenal papilla, located on the second segment of the C-shaped duodenum. This anatomical landmark is important for gastroenterologists as they do endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures to cannulate the major papilla of the duodenum.

Clinical Significance

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is a condition that occurs due to hyperproliferation of the smooth muscle of the pyloric sphincter. This condition occurs in 0.5% to 1% of infants and manifests with forceful or projectile non-bilious vomiting shortly after feeding. The large pyloric sphincter prevents gastric emptying into the duodenum and causes the infant to have forceful vomiting episodes. The vomitus itself will be non-bilious due to the blockage being before the duodenal papilla enters the duodenal cavity. This hypertrophic sphincter can sometimes be felt as an “olive-shaped mass” or as a small knot at the right costal margin in the epigastric region on the patient. Treatment is usually surgery that includes a myomectomy procedure of the pyloric sphincter.[5]

Duodenal atresia occurs due to complete closure of the lumen of the duodenum. This condition can be entertained if the mother of a fetus presents with polyhydramnios or with newborns that present with signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction. Upon x-ray of the abdomen, a common radiographic finding in these patients is the “double-bubble-sign.” This is due to the air located in the stomach and the proximal duodenum separated by the pyloric sphincter. The cause of these atresias is commonly caused by vascular accidents or ischemic incidents during development. There has been an association with this condition and with patients diagnosed with Down syndrome. Treatment is surgical which includes a duodenoduodenostomy.[6]

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome is a condition that occurs when the duodenum is compressed at its third or fourth portion by the superior mesenteric artery and the abdominal aorta. Patients with this syndrome typically include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, early satiety, and abdominal distention. This compression occurs when the retroperitoneal fat or lymphatic tissue that protect the duodenum from compression are decreased. This can be caused by congenital insults and acute insults. Congenital insults include an asthenic body build, a high insertion of the duodenum at the ligament of Treitz, or a low origin of the superior mesenteric artery. With any of these predispositions, it is possible that retroperitoneal tumors, lumbar lordosis, abdominal trauma, rapid linear growth spurt, weight loss, and starvation can cause this protective covering of the duodenum to decrease and allow compression of the duodenum by the SMA and the abdominal aorta.

The duodenum is also of clinical significance because it is prone to ulceration most commonly by a patient who is infected with Helicobacter pylori. This is of special importance due to the special circumstance if this ulcer is located in the posterior portion of the duodenum that could potentially lead to a life-threatening injury to the gastroduodenal artery.

Other clinical significant notes of the duodenum include patients that are suspected to have Celiac disease, a biopsy of the duodenum is required. Also, a duodenal hematoma can also present as a traumatic injury from a seatbelt or direct blow to the abdomen. Other pathologies of the duodenum include duodenal cancer, which is rare. It is usually an adenocarcinoma and may be associated with a polyposis syndrome like familial polyposis coli.