Introduction

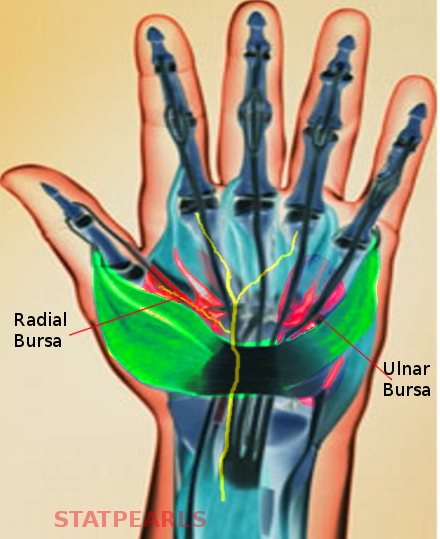

The largest organ of the human body is the skin. This organ is comprised of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, which have additional layers that are categorized by the structures and characteristics present within each layer. Below the skin lies muscles, ligaments, tendons, soft tissue, and bone. Bursa, and bursas or bursae for the plural form, is an important lubricated fluid-filled thin sac located between bone and surrounding soft tissue, bones and tendons, and/or muscles around joints, and are useful to the human body by reducing tension and negative effects of wear-and-tear at points of friction and provide resistance-free movement by the human body.[1] The bursa sac is lined by a synovial membrane or synovium, which contains the synovial fluid that is comparable to the consistency of raw egg whites. The sac is semi-permeable and allows certain materials to flow in and out of its membrane; when there is an injury to the bursa, fluid, such as blood, can fill the sac and cause irritation. All 160 bursae that are present within the adult body vary in size and shape depending on the person and the location of the bursa; some bursae are not present at birth and develop as friction increases with age.[2] Bursae are classified as superficial when their structure lies between bones, tendons, or skin, and deep when they’re between bones and muscles.[3] See Image. Hand Bursae.

Structure and Function

Classifications of Bursae

Bursae are primarily synovial bursae that are constant in their location and predictable. They tend to form during embryonic development. The other, less common type is the adventitious bursa, which tends to form in response to repeated forces or friction originating within the body or from outside the skin.

Adventitious

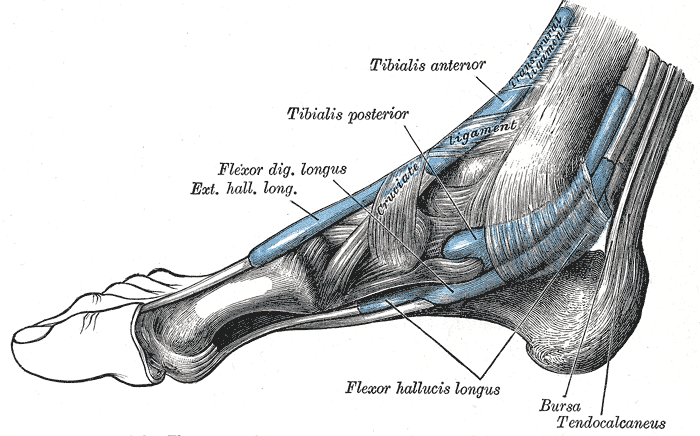

The adventitious bursae exist in soft tissues as a way to relieve repeated friction from natural movements or unusual and damaging pressure; this is the only bursa that is non-native. These bursae cover bony prominences throughout the body and are commonly called accidental bursae. An example of an adventitious bursa that develops relative to hallux valgus on the inner big toe base is a bunion.[4] A major factor in the development of this bursa is wearing tightly fit shoes and improper foot care. Occasionally, few bony deformities that are subcutaneous can be a causative factor. See Image. Extrinsic Foot Muscles.

They are histologically characterized by mucoid and myxomatous degeneration of connective tissue and do not have the true endothelial intima lining.

Synovial

The most bursa in the human body are synovial bursae, which are most common near large joints in the extremities, are located between tissues, and are defined as thin, synovial membrane sacs.[5] A capillary film of synovial fluid on the inner surface of the sac surfaces acts as a lubricant. Depending on their position, they classify as subcutaneous, subtendinous, submuscular, or subfascial bursae. At times they communicate with the joint cavity; in such cases, their synovial membranes are continuous.

Their lining is a cellular intima layer, which secretes the lubricating fluid.

Embryology

The skin develops from the ectoderm and mesoderm layers of the primitive embryo. The ectoderm contributes towards the epidermis and some of the skin glands, while the bulk of the connective tissue derives from the mesoderm layer.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Predominantly the synovial bursae have good blood and lymphatic supply. When there is any trauma or infection, the cardinal signs of inflammation, namely redness pain, and swelling of the sac and its surrounding skin can present in superficial bursae, on clinical examination. They can also produce signal changes in proper imaging like MRI and ultrasound scans.

Physiologic Variants

Location of Bursa

Subcutaneous

The subcutaneous bursae can be classified as adventitious when they become abnormal and develop a distinct wall. These bursae appear between the subcutaneous tissue and deep fasciae junction, or bony prominences.

Submuscular

The submuscular bursae exist between adjacent muscles or muscles and bony prominences.

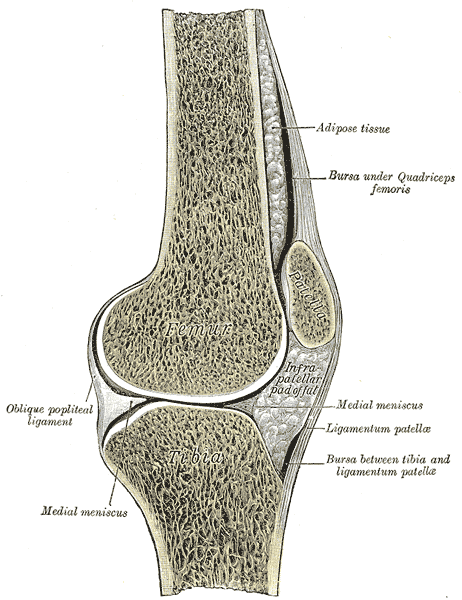

Bursa naming is according to the location within the human body: bursae of the upper body include subacromial, subscapular, and olecranon; bursae of the hip include ischiogluteal, iliopsoas, and trochanteric; bursae of the knee include medial collateral ligament, pes anserinus, prepatellar, infrapatellar, popliteal bursa; and the ankle bursa is Retrocalcaneal. See Image. Sagittal Section of the Right Knee Joint.

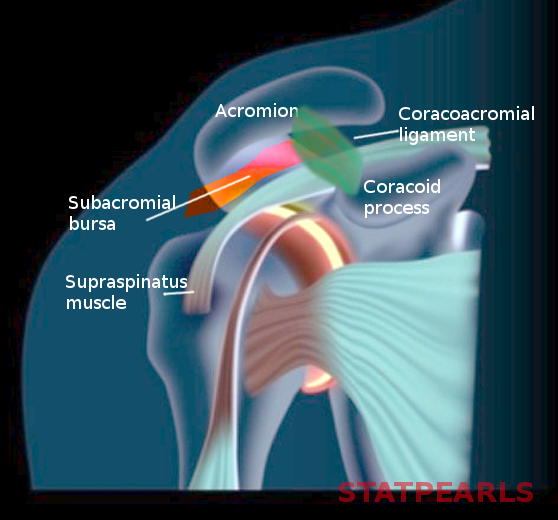

Upper Body Bursae

The subacromial bursa lies between the acromion and the rotator cuff. This bursa protrudes laterally from below the acromion when the arm is at rest and moves medially below the bone when the person lifts their arm away from the center of the body. See Image. Subacromial Bursa.

The subscapular bursa lies between the frontward facing scapula surface and the backward-facing chest wall.

There are two olecranon bursae with the first bursa lying between the tricep tendons, the posterior elbow ligament, and the olecranon, while the second bursa lies more superficially between where the triceps attaches to the olecranon and the skin.

Hip Bursae

The ischiogluteal bursa lies deep within the gluteus maximus and surfaces the ischial tuberosity.

The iliopsoas bursa is known for being the largest bursa in the human body, which extends into the iliac fossa and lies between the lesser trochanter and the iliopsoas tendon.

The trochanteric bursa extends superficially between the tensor fascia latae and the skin while also lying deeply between the tensor fasciae latae and the greater trochanter.

Knee Bursae

The medial collateral ligament bursa lies between the superficial and deep medial collateral ligament in the knee.

The pes anserinus bursa lies between the hamstring tendons and the superficial collateral ligament.

The prepatellar bursa is located anteriorly over the knee’s patella and below the skin.

The infrapatellar bursa contains a superficial component, as well as a deep component. The superficial bursa is between the patellar ligament and the skin, while the deep bursa is between the patellar ligament and the proximal aspect of the anterior tibia.

The popliteal bursae are known as baker cysts and lie in the posterior joint capsule of the knee.

Ankle Bursae

The retrocalcaneal bursa is at the back of the heel and lies deep to the Achilles tendon and above the calcaneus bone. Occasionally you can see bursa over the medial malleolus, the subcutaneous medial bursa, and a bursa behind the heel called the subcutaneous calcaneal bursa.

Surgical Considerations

Inflamed Bursae

Irritation to any part of the body can cause inflammation. Any inflammation of the bursa is called bursitis. This inflammatory response can result from a minor, repetitive impact on the surrounding bursa area, or can occur from sudden and more urgent injuries.[6] Other factors that affect bursitis formation include age, a body’s elasticity and ability to tolerate stress, and diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis or thyroid disease, or infection. Additionally, any overuse or impairment to the bursa or surrounding body parts- joint, bone, tendon, muscle, or ligament- can increase the risk of developing bursitis. Common symptoms of bursitis may include discomfort, tenderness, redness, or swelling in the affected area, difficulty or loss of movement, and fever.[7]

Septic Bursitis and Surgical Considerations

Patients can also present with sudden onset of redness and pain in a previously inflamed bursa. That could be as a result of infection, which can be due to poor host immune response or a direct inoculation with penetrating trauma or an insect bite.[8] When the conservative measures to treat the painful and infected bursa have failed, surgical inversion may be required to drain the collection.[9]

In certain scenarios, the clinical findings might not be adequate to differentiate septic bursitis from friction, crystal deposition, or inflammatory conditions. Aspiration under aseptic precautions and, if required with ultrasound guidance, followed by oral antibiotics, is the recommendation.[10] Aspirate should have microbiology and biochemistry assessments. Antibiotics should be changed depending on the culture and sensitivity results.

Surgical treatment for recurrent bursitis is not standardized with supporting evidence. There is a considerable variation in treatment modalities across the globe. The patient should be made aware of the potential risks associated with surgical excision, including infection, delayed healing, sinus formation, the persistence of pain, and recurrence.[11]

Clinical Significance

Bursitis can be treated through many interventions including rest, stretching and physical therapy, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen, aspirin, naproxen, COX-2 inhibitors, topical medications such as lidocaine patches, NSAIDs, or analgesics, aspiration to drain the excess fluid to relieve bursa pressure, corticosteroid injections, antibiotics, RICE: rest, ice, compression, elevation, and in some cases- surgery.[12] The required treatment for bursitis depends on the location of the inflamed sac, the severity of the inflammatory response, and the duration of the condition.

Sub-acromial bursitis is a common diagnosis in patients presenting with shoulder pain, particularly in a young and active population. Often their symptoms are exaggerated with over-head activities. A thorough clinical examination supported with appropriate imaging is vital in confirming the diagnosis and drawing up a treatment plan. The vast majority of patients notice improvement with activity modifications, rest, analgesics, and appropriate physiotherapy. Referral to specialists for surgical intervention is the recommended next step when these modalities fail.

Clinicians can adequately manage trochanteric bursitis with anti-inflammatory medications, rest, and physiotherapy. Ultrasound-guided steroid injections are proven to provide good relief in a few patients while there is increasing evidence for injecting platelet-rich plasma.[7][13][14]

Additionally, steroid injections require precise pre-procedural evaluation, technique, and post-procedural guidance. The research completed on these injections proves the effectiveness of the current methods to treat pathological bursae in most anatomic locations.[15] During the pre-procedural evaluation, the patients are advised to complete relevant lab work and imaging, while also discussing allergies, medical history, and current medications, and signing consents.[15] Once the patient is cleared by the physician for the ultrasound-guided bursal injections, the physician will examine the bursa and decide the most appropriate medical items and equipment to use. Most often, a 22-gauge needle or a 25-gauge needle will be used to aspirate the fluid from the infected bursa.[15] If the fluid is viscous, a thicker gauge needle may be recommended and used.

The steroids used during ultrasound-guided injections consist of different concentrations and properties, so it is important to know which steroids to use in different anatomical locations. The common steroids used include methylprednisone, betamethasone, or triamcinolone.[15] Research proves that these steroids have lower solubility than a steroid such as dexamethasone.[15] The appropriate steroid solution lasts longer at the injection site compared to non-particulate steroids. [15]

To confirm the correct anatomical location, a small amount of lidocaine may be injected into the surrounding areas of the bursa prior to the steroid injection.[15] This technique can be helpful to identify bursae that are difficult to locate without distention. Before administering any medication, the providers should assess and document evidence of allergy reactions. If the patient has a documented allergy to lidocaine or other similar anesthetics, then the provider should use an anesthetic such as chloroprocaine.[15]

Although ultrasound-guided bursal injections are difficult to execute, these procedures establish more accurate results compared to injections into bursae by palpation of certain body sites.[15] The post-procedural instructions include keeping the area dry for 24 hours, completing a functional assessment and pain assessment, and being informed that the full relieving effects from the steroid injection may take up to seven days.[15]