Continuing Education Activity

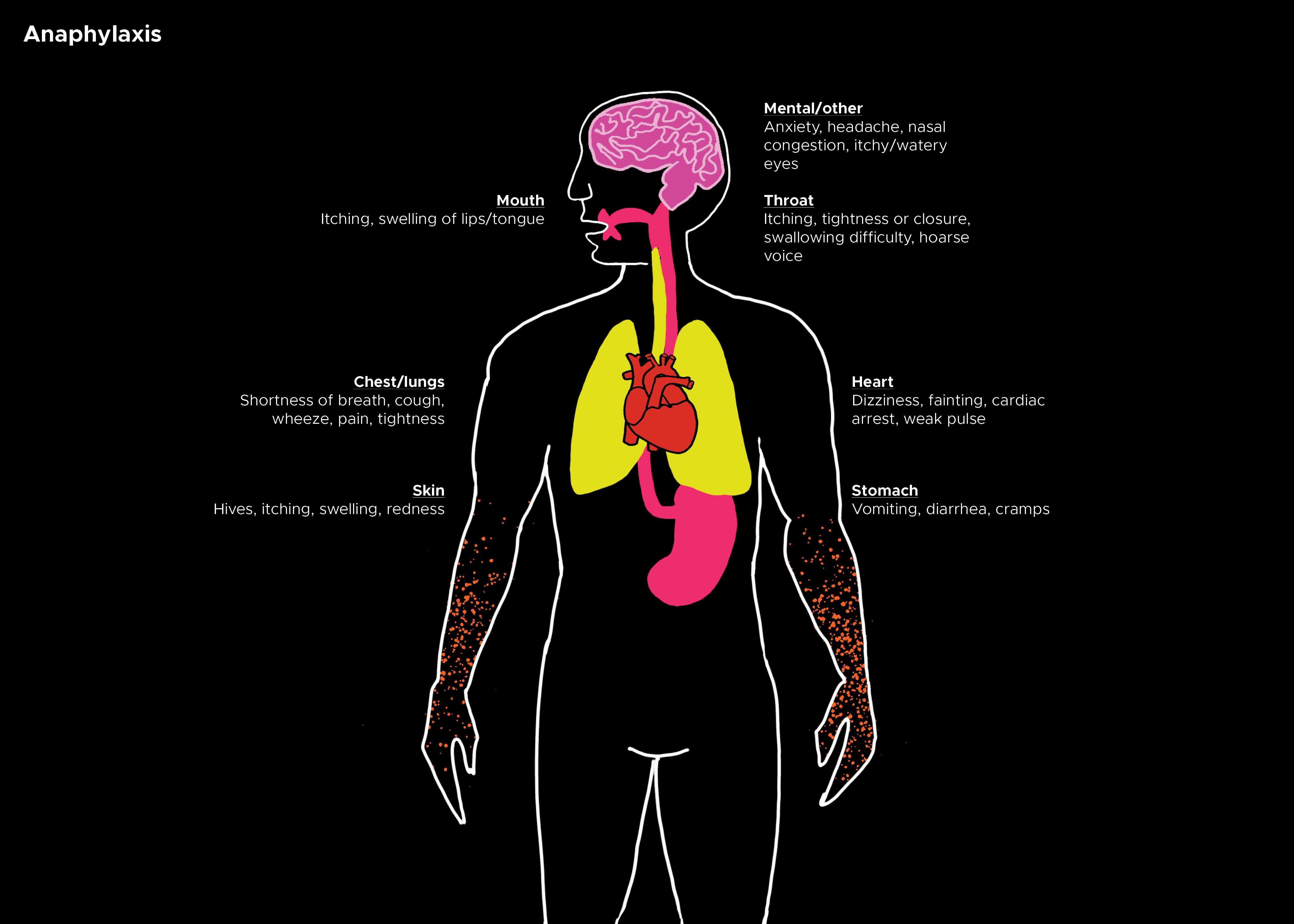

Anaphylaxis is an acute, life-threatening hypersensitivity disorder, defined as a generalized, rapidly evolving, multi-systemic allergic reaction. Anaphylactic reactions were classified as IgE-mediated responses, while anaphylactoid reactions as IgE-independent events. Physical presentations of anaphylaxis range from mild skin flushing and pruritus to severe respiratory symptoms. This activity describes the evaluation and treatment of anaphylaxis and explains the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the common inciting sources in the etiology of anaphylaxis.

- Describe the IgE-mediated immune response in the pathophysiology of anaphylaxis.

- Summarize the clinical criteria used in the evaluation of anaphylaxis.

- Outline the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes in patients with anaphylaxis.

Introduction

Anaphylaxis is a common medical emergency and a life-threatening acute hypersensitivity reaction. It can be defined as a rapidly evolving, generalized, multi-system allergic reaction. Without treatment, anaphylaxis is often fatal due to its rapid progression to respiratory collapse. Historically, anaphylactic reactions were categorized as IgE-mediated responses, while anaphylactoid reactions were categorized as IgE-independent events. Recently, these terms have been consolidated into a single diagnosis of anaphylaxis. Regardless of causation, the resultant clinical state and treatment for each reaction are identical; therefore, this unified terminology is currently the accepted vernacular.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Common inciting sources may include exposure to certain medications, foods, or insect stings. Immunotherapy injections directed at improving overall allergic response can induce a hyper-acute reaction. Latex hypersensitivity is occurring in increased prevalence, and as with any hypersensitivity, anaphylaxis is an inherent risk. Occasionally the offending agent is not identified; these reactions are identified as idiopathic anaphylaxis.[4][5][6]

Alpha-gal anaphylaxis: This involves an IgE antibody response to mammalian galactose alpha-1,3-galactose.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that the world population has a lifetime prevalence of 1% to 3%, though the prevalence is increasing. While reactions can occur in any age group, they are most commonly noted in the younger population and developed countries. Unfortunately, anaphylaxis is often misdiagnosed or not diagnosed at all. The consequences of missed or delayed diagnosis result in increased morbidity and mortality.[7][8][9]

Pathophysiology

Anaphylaxis is typically an IgE-mediated (type 1) hypersensitivity reaction that involves the release of numerous chemical mediators from the degranulation of basophils and mast cells after re-exposure to a specific antigen. IgE crosslinking and resultant aggregation of high-affinity receptors induce the rapid release of stored chemical mediators. These chemical mediators include histamine, tryptase, carboxypeptidase A, and proteoglycans. Via activation of phospholipase A, cyclooxygenases, and lipoxygenases, they then form arachidonic acid metabolites, including leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and platelet-activating factors.[10][11] The inflammatory response is then mediated by TNF-alpha (tumor necrosis factor), both as a preformed and late-phase reactant. The detailed physiology of these chemical mediators is as follows:

-

Histamine increases vascular permeability and vasodilation, leading to hypoperfusion of tissues. The body responds to these changes by increasing heart rate and cardiac contraction.

-

Prostaglandin D functions as a bronchoconstrictor with simultaneous cardiac and pulmonary vascular constriction. It also potentiates peripheral vasodilation, thus contributing to the hypo-perfusion of vital organs.

-

Leukotrienes add to bronchoconstriction, vascular permeability, and induce airway remodeling.

-

The platelet activation factor also acts as a bronchoconstrictor and increases vascular permeability.

-

TNF-alpha activates neutrophils (as part of stress response leukocytosis) and increases chemokine synthesis.

Histopathology

Rapid mast cell and basophil degranulation are attributed as the causation for the overactive immune response that culminates in the clinical picture of anaphylaxis.

History and Physical

Clinical presentation often begins as a mild allergic reaction. The primary symptoms depend on the mode of exposure to the causative antigen. While cutaneous flushing with pruritus and urticaria are common, they may not develop until after respiratory symptoms occur, which is common in oral exposures. Fullness or a "lump in the throat," persistent clearing of the throat, or difficulty breathing are all concerning symptoms of anaphylaxis and should be treated aggressively. Other respiratory symptoms include hoarseness, wheezing, and stridor. If any of these symptoms are present, rapid treatment should be initiated with intramuscular epinephrine.

Anaphylaxis is most often a rapidly evolving presentation, usually within one hour of exposure. Roughly half of the anaphylactic-related fatalities occur within this first hour; therefore, the first hour after the initial symptom onset is the most crucial for treatment. It is important to note that the more rapid the onset and progression of symptoms, the more severe the disease process. Morbidity and mortality are most often related to loss of airway and distributive shock. Early recognition and aggressive treatment greatly reduce the risk of adverse outcomes.

The first hour is not the only time of concern, however, as anaphylactic reactions can also present in a biphasic manner in up to 20% of cases. Even after successful management of the initial presenting symptoms, there can be a recurrence of symptoms peaking 8 to 11 hours after the initial reaction. While the biphasic response is only clinically significant in 4 to 5% of patients with diagnosed anaphylaxis, the potentially fatal second reaction should not be dismissed after treatment of the initial reaction.

While a majority of the focus is placed on the above symptoms of respiratory, cutaneous, and hypotension, it is important to understand and evaluate for any other signs of end-organ damage from hypo-perfusion. This may include abdominal pain and cramps, vomiting, hypotonia, syncope, or incontinence. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are present in 25 to 30% of patients. While the loss of airway control due to laryngeal edema is the primary concern, one must not fail to recognize anaphylaxis in a patient who does not endorse upper airway edema or respiratory complaints.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of anaphylaxis is a clinical diagnosis; thus, laboratory studies or other diagnostics are not necessary. Most anaphylactic deaths occur within the first hour after antigen exposure. Rapid recognition and action are imperative.[2][12][13]

Consideration for anaphylaxis is appropriate in the presence of 2 or more involved systems, even in the absence of airway involvement or hypotension (see above). A consensus criterion has been constructed to improve clinical recognition to prevent delayed treatment, as this poses a great risk to patients.

Clinical Criteria for Anaphylaxis (1 of the following with onset within minutes to hours)*

Unknown exposure to an antigen yet rapidly developing urticaria or other skin/mucosal layer symptoms associated with any one of the following:

- Respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, wheezing, stridor, hypoxemia, inability to maintain patency; persistent cough and/or throat clearing can be heralding symptoms)

- Hypotension (systolic less than 90 mm Hg or a decrease of greater than 30% from baseline)

- Signs or symptoms of end-organ dysfunction, for example, hypotonia, syncope, incontinence

Likely exposure to an antigen and symptoms involving any 2 of the following body systems:

- Integumentary symptoms: Skin or mucosal layer (rash, pruritus, erythema, hives, swelling of the face, lips, tongue, or uvula)

- Respiratory symptoms: Dyspnea, wheeze, stridor, hypoxemia, inability to maintain patency; persistent cough and/or throat clearing can be heralding symptom

- Hypotension: Systolic less than 90 mm Hg or a decrease of greater than 30% from baseline

- Gastrointestinal symptoms: Persistent painful cramps or vomiting

Known exposure to an antigen and hypotension (systolic less than 90 mm Hg or a decrease of greater than 30% from baseline)

*Note: It is not required to meet these criteria to treat, only to serve as a guide for diagnosis

Angioedema can also mimic these symptoms. A key differentiation between angioedema and anaphylaxis is urticaria, the oral symptoms and need for airway control can otherwise mimic each other. When in doubt, treat aggressively.

Laboratory testing is of little to no use, as there is no accurate testing for diagnosis or confirmation. Serum histamine is of no use due to transient elevation and late presentation. Serum tryptase can be considered for confirmation of an anaphylactic episode as it remains elevated for several hours; however, as a diagnostic modality, this has low sensitivity.

Kounis syndrome (allergic angina): This is myocardial infarction or ischemia that can occur in the setting of anaphylaxis.[14]

Treatment / Management

Triage

Triage any allergic reaction with urgency as they are at risk for rapid deterioration with the development of anaphylaxis, if not already anaphylactic.[15][16][17]

Airway

Airway management is paramount. Thoroughly examine the patient for airway patency or any indications of an impending loss of airway. Perioral edema, stridor, and angioedema are very high risk, and obtaining a definitive airway is imperative. Delay may reduce the chances of successful intubation as continued swelling occurs, increasing the risk for a surgical airway.

Decontamination

After the airway is secured, the decontamination of offending agents (if known) is the next priority to prevent continued exposure and clinical worsening. Remove any stingers, if present. Do not attempt gastric lavage in cases of ingestion, as this may not be effective and delays treatment.

Epinephrine

Epinephrine is given through intramuscular injection and at a dose of 0.3 to 0.5 mL of 1:1,000 concentration of epinephrine. Pediatric dosing is 0.01 mg/kg or 0.15 mg intramuscularly (IM) (epinephrine injection for pediatric dosage). Intramuscular delivery has proven to provide more rapid delivery and produce better outcomes than subcutaneous or intravascular. Note if intravenous (IV) epinephrine is to be given, the concentration required is 1:10,000; see the next paragraph. The thigh is preferred to the deltoid when possible. Repeat studies have shown that providers often wait too long before giving epinephrine; it is the treatment of choice, and the rapid benefit much outweighs the risks of withholding treatment. While most patients require only a single dose, repeat doses may be given every 5 to 10 minutes as needed until symptoms improve.

- If patients require multiple doses, a continuous infusion of epinephrine may be considered; start an initial IV infusion of 0.1 mg of 1:10,000, given over 5 to 10 minutes. If more is required, begin infusion at 1 microgram per minute and titrate to effect. Stop IV infusion if arrhythmia or chest pain develops. The risk of cardiovascular complications is much greater for IV epinephrine. For beta-blocked patients, close blood pressure monitoring is suggested due to the risk of unopposed alpha-adrenergic effects from epinephrine.

IV Fluid Resuscitation

Anaphylaxis induces a distributive shock that typically is responsive to fluid resuscitation and the above epinephrine. One to 2 L or 10 to 20 mL/kg isotonic crystalloid bolus should be given for observed hypotension. Albumin or hypertonic solutions are not indicated.

Adjunctive Therapies

Often when anaphylaxis is diagnosed, co-treatment is initiated with steroids, antihistamines, inhaled bronchodilators, and vasopressors. Glucagon can also be used if indicated. These agents can assist in refractory initial anaphylaxis or aid in the prevention of recurrence and biphasic reactions.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are given for the reduction of length or biphasic response of anaphylaxis. There is minimal literature to support this use, specifically in anaphylaxis, but it has been proven effective in reactive airway diseases. Therefore, the use, dosages, and proposed mechanism of action mimic those of airway management protocols.

Methylprednisolone (80 to 125 mg IV) or hydrocortisone (250 to 500 mg IV) are the accepted treatments during the acute phase, after which oral treatment of prednisone (40 to 60 mg daily or divided twice per day) is continued for 3 to 5 days. Again, if the source is unknown and/or there is a concern for a prolonged time prior to physician follow up steroid taper of up to 2 weeks may be provided. Mineralocorticoid activity is responsible for fluid retention; in those at risk, dexamethasone and methylprednisolone are the preferred agents as they induce the least mineralocorticoid effect.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines are often routinely used; the most common is H1 blocker administration of diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg IV/IM. While the clinical benefit is unproven in anaphylaxis, its utility is evident in more minor allergic processes. In severe cases, H1 blockers such as ranitidine (50 mg IV over 5 minutes) or cimetidine (300 mg IV) may also be used in conjunction with H-blocker as there is evidence suggesting histamine has crossover selectivity of receptors. Note that cimetidine has multiple precautions in at-risk populations such as renal or hepatic impaired patients or those taking beta-blockers. While IV is the initial route during stabilization, once the patient is stabilized, they may be switched to oral if continued therapy is desired.

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilators are useful adjuncts in patients with bronchospasm. Patients with previous histories of respiratory disease, most notably asthma, are at the highest risk. Treated with inhaled beta-agonists are the first-line treatment in wheezing; albuterol alone or as ipratropium bromide/albuterol. If there is refractory wheezing, IV magnesium is appropriate with dosage and treatment similar to severe asthma exacerbations.

Vasopressors

Vasopressors may be substituted when a patient requires more doses of epinephrine but has unacceptable side effects from the epinephrine IV infusion (arrhythmia or chest pain). In which case there has been no clear second line pressor identified, treatment guidelines would follow that of any other patient in hypotensive shock.

Glucagon

Glucagon is the reversal agent for beta-blockers and can be used as such if needed in cases where anaphylaxis is resistant to treatment in patients with beta-blockade. Known side effects include nausea, vomiting, hypokalemia, dizziness, and hyperglycemia.

A therapeutic agent under research:

Sirtuin 6[18]

It is a NAD-dependent deacetylase that suppresses protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type C transcription. This, in turn, leads to negative regulation of the FcERI signaling cascade in mast cells. Hence, activation of Sirt6 can be tried as a therapeutic strategy for anaphylaxis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses include:

- Angioedema

- Anxiety

- Arrhythmias

- Asthma

- Carcinoid syndrome

- Epiglottitis

- Foreign-body airway obstruction

- Gastroenteritis

- Mastocytosis

- Myocardial ischemia/infarction

- Seizure

- Vasovagal episode

- Vocal cord dysfunction

Prognosis

With rapid and adequate treatment and monitoring, the risk of morbidity and mortality is low. Rapid access to medical care and rapid acknowledge of the disease process are essential to patient prognosis. As stated above, the first hour after symptoms exposure is responsible for half of the related fatalities.[15][19][10]

Hospital admission is required in 4% or less of acute allergic reactions diagnosed in the emergency department. If epinephrine is required, as in cases of anaphylaxis, complete resolution is noted. Emergency department (ED) observation for 4 hours is recommended. If no further intervention is required, the patient can be discharged home with a prescription for an epinephrine autoinjector, and follow-up is appropriate. If the patient requires airway intervention, is refractory to treatment, or is deemed unstable, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) for close monitoring is advised. Patients with a history of biphasic reactions, severe reactions, beta-blocker use, older, those who live alone, or those with poor access to health care or deemed at risk should be monitored longer.

Along with the prescription for an epinephrine pen, antihistamines and corticosteroids are appropriate for 3 to 5 days. If the inciting source is unknown and the patient will have a prolonged time before follow-up, consider corticosteroid use for 1 to 2 weeks with an appropriate taper. Also, consider writing for multiple epinephrine autoinjectors to ensure they are kept in various locations (home, school, work, and vehicle). Educate and document the need for 24-hour access to the epinephrine autoinjector if symptoms begin to recur.

Patients with severe allergic reactions and anaphylaxis who take beta-blockers are at greater risk for prolonged or more severe symptoms; consider other classes of medication if possible. Patients may also consider obtaining medical alert bracelets or the like for assistance in the future.

Complications

The main complications which can occur following an anaphylactic reaction include the following:

- Wheeze

- Stridor

- Hypoxemia

- Hypotension

- End-organ dysfunction and

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patients should be provided with multiple epinephrine autoinjectors with 24-hour access and educated to use them when symptoms begin to recur.

Patients should be made aware of the importance of wearing medical alert bracelets or the like for assistance in the future.

Pearls and Other Issues

There is no absolute contraindication to treatment with epinephrine in anaphylaxis.

Treatment includes airway, decontamination, epinephrine 1:1000 0.3 to 0.5 mg IM, and a fluid bolus. Then start secondary treatments. Avoidance of inciting agents is the key to prevention.

Patients should always be provided with an epinephrine auto-injector and instructed on how to use it. Patients should also be given outpatient follow-up with an allergist and immunologist to assist in the determination of inciting agents and prevention of future reoccurrences. Once the patient is stabilized, short-term desensitization procedures can be undertaken.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An Evidence-based Approach to Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is a rapid systemic and unpredictable disorder that is life-threatening. The disorder often occurs after exposure to certain antigens, which in most cases are insect venom, food, or medications. The condition is immune-mediated and rapidly induces symptoms. For those who have not encountered anaphylaxis, the diagnosis can be difficult. In the United States, the rates of anaphylaxis have doubled over the past 20 years, and at least 1500 people die from the disorder each year. The potentially life-threatening nature of the disorder makes it imperative that one be prepared and offer prompt treatment. This is one of the few medical disorders during which a healthcare worker does not have the luxury of time. Having epinephrine on hand can be life-saving if one wants to avoid a fatal outcome. However, despite considerable evidence that epinephrine is the drug of choice, it is under-used. Instead, many healthcare workers use an antihistamine, a drug that does not prevent or relieve all the manifestations of anaphylaxis.[20] In addition, the antihistamine does not even start to work for 1 to 3 hours, depending on the route of administration. Given these findings, it is imperative that all healthcare workers be educated on anaphylaxis and its treatment. Evidence indicates that the following healthcare workers are critical for managing and preventing anaphylaxis.

Since people may develop anaphylaxis almost anywhere, it is important that all healthcare workers know the signs and symptoms of the disorder and know how to administer epinephrine.

The pharmacist is in a key position to educate the patient and family about anaphylaxis. Plus, the pharmacist can teach the patient and family to carry epinephrine with them all the time

In addition, all physicians, nurses, and other allied healthcare workers need to know the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis and how to administer epinephrine.

The treating physician should try to reduce all the trigger factors and ensure optimal management of asthma.[21] (Level III)

Outcomes

Despite awareness of the seriousness of anaphylaxis, treatment of anaphylaxis is not optimal. At least 1500 die each year from a condition that can be treated and even prevented. Although the seriousness of anaphylaxis is well established, there are no randomized trials to determine the effectiveness of antihistamines and how it compares to epinephrine. Further, what outcomes to measure after treatment has never been defined. In the absence of any solid clinical data, it is important that all healthcare workers are prepared to deal with anaphylaxis as members of an interprofessional healthcare team and possess the knowledge and skills to administer epinephrine and coordinate with other team members to arrange the appropriate follow-up care, leading to better patient outcomes.[22] [Level 5]