Continuing Education Activity

The greater occipital nerve transverses the upper neck and posterior occiput. Dysfunction of the nerve is associated with several commonly encountered headaches, including occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic, and cluster headache. This painful disorder can reduce the quality of life and is associated with a large socioeconomic burden. A greater occipital nerve block (GON-block) involves injecting an anesthetic near the greater occipital nerve to relieve pain and inflammation. This activity outlines how to perform the greater occipital nerve block procedure while utilizing relevant anatomy. This activity will discuss targeted outcomes as well as possible complications.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications for an occipital nerve block.

- Describe the technique used to perform an occipital nerve block.

- Review alternative techniques for performing an occipital nerve block.

- Outline potential complications of occipital nerve blocks.

Introduction

Greater than 15% of the population reports experiencing a severe, debilitating headache. Headaches are ranked tenth as the most common health problem and first as the most common nervous system disorder. Approximately 1.4 to 2.2% of the global population experiences headaches at least 15 days per month.[1] This painful disorder can reduce the quality of life and is associated with a large socioeconomic burden.[2][3] For this reason, the management of headache pain is becoming an increasingly popular topic among specialists.

The greater occipital nerve block is a growing interest among many providers for headache treatment. The greater occipital nerve (GON) transverses the upper neck and posterior occiput. Dysfunction of the nerve is associated with several commonly encountered headaches, including classic migraine, occipital neuralgia, cervicogenic, and cluster headache. The GON-block can achieve significant analgesia as a primary headache treatment and be used as a second-line treatment when other methods have failed. Symptom improvement frequently varies from patient to patient and can be very difficult to predict.[4]

When a GON-block is successful, pain typically improves after 20-30 minutes and can last for several hours to several months. For patients impacted by severe or frequent headaches, this treatment can substantially improve their quality of life. If more than three nerve blocks are required in six months, a provider should explore additional, alternative treatment options.[5]

Anatomy and Physiology

Peripheral nerve blocks such as the GON-block can be a safe and effective pain treatment modality when performed by a provider with adequate knowledge of head and neck anatomy.[6] Three occipital nerves arise from C2 and C3 spinal nerves and innervate the posterior scalp. The three occipital nerves include the greater occipital nerve (GON), the lesser occipital nerve (LON), and the third occipital nerve (TON).[7]

The greater occipital nerve is the largest of the three occipital nerves, innervating the posterior scalp. The GON sensory fibers arise from the dorsal primary ramus of the C2 spinal nerve and then ascend through the fascial plane between the obliquus capitis inferior and semispinalis capitis. The fibers pierce the semispinalis capitis and travel deep to the trapezius muscle until exiting the aponeurosis inferior to the superior nuchal line. At this location, the occipital nerve lies subcutaneously and just medial to the occipital artery. This tortuous path allows a potential source of nerve irritation and compression.[8]

The frequent co-occurrence of neck pain and headache can also be attributed to the greater occipital nerve and its direct role in what is known as the trigemino-cervical complex (TCC).[9] The C2 sensory neurons of the GON share common sensory innervation with the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC), creating a common nociceptive pathway between the head and neck. This continuum between the trigeminal and cervical fibers allows the greater occipital nerve block to represent a reasonable option for acute treatment and prevention of both primary and secondary headaches.[5]

Indications

Nerve blocks targeting the greater occipital nerve can be used as the primary treatment of headaches but are more often used to treat intractable headaches when other methods have failed.[10]

The greater occipital nerve block can be an effective and safe treatment option for several headache disorders, including occipital neuralgia, migraine, post-dural puncture headache, cervicogenic headache, and cluster headache.[5] The nerve block can also reduce associated symptoms resulting from nerve irritation, including tinnitus and otalgia.[11]

Patients who report allodynia of the scalp and those who have reproducible pain with palpation of the GON are most likely to achieve the desired analgesic response after receiving treatment. The GON-block is also a viable treatment option for headaches in the elderly and pregnant population who have comorbidities that prevent them from receiving other first-line treatment regimens.[12]

Contraindications

The greater occipital nerve block is generally a well-tolerated, low-risk procedure. Absolute contraindications include patient refusal, anesthetic allergy, open skull defect, and infection at the procedure site. It is also contraindicated to perform the nerve block at a surgical site due to the risk of intracranial infiltration.[7]

Other relative contraindications that should be considered before performing the procedure include:

- Coagulopathy

- History of Arnold Chiari malformation[13]

- Inability to lie still in a prone or sitting position

Equipment

The GON-block can be performed relatively quickly, easily, and inexpensively. Only minimal equipment is required. The provider has the option to inject anesthetic alone or may also choose to inject a combination of anesthetic and steroid. Studies suggest no difference in short and long-term migraine pain control when the anesthetic is injected alone or in combination with a steroid. In contrast, the addition of steroids is very effective for treating cluster, cervicogenic, and post-dural puncture headaches.[14]

Required equipment for a single GON-block includes:

- 5 cc syringe

- 25-gauge needle

- Povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine

- Anesthetic

- Lidocaine 2% (2 mL)

- Bupivacaine 0.5% (2 mL)

- Anti-inflammatory

- Methylprednisolone 40 mg/mL (2 ml)

- Dexamethasone 2 mg/mL (2 ml)

Toal injection volume should not be greater than 4 mL. If lidocaine and bupivacaine are combined, the ratio should be 1 to 1 to 1 to 3.[5][7]

Personnel

A greater occipital nerve block should be performed by a medical professional who has knowledge of head and neck anatomy and has been trained in local anesthesia. A nurse or nursing assistant can assist with patient positioning. Nursing can also help to monitor vitals and watch for signs and symptoms associated with adverse reactions.

Preparation

The medical provider should obtain written informed consent from the patient or their decision-making proxy before performing the GON-block. Once the risks and benefits have been explained, the patient should be placed in an examination room on a monitor. All necessary equipment and medications should be available at the bedside.

Technique or Treatment

The GON-block can be performed unilaterally or bilaterally. However, no method has been identified as superior to the other.[15]

The following steps will discuss how to perform the greater occipital nerve block:

- Optimally position the patient by placing them in a seated or prone position with the neck slightly flexed.

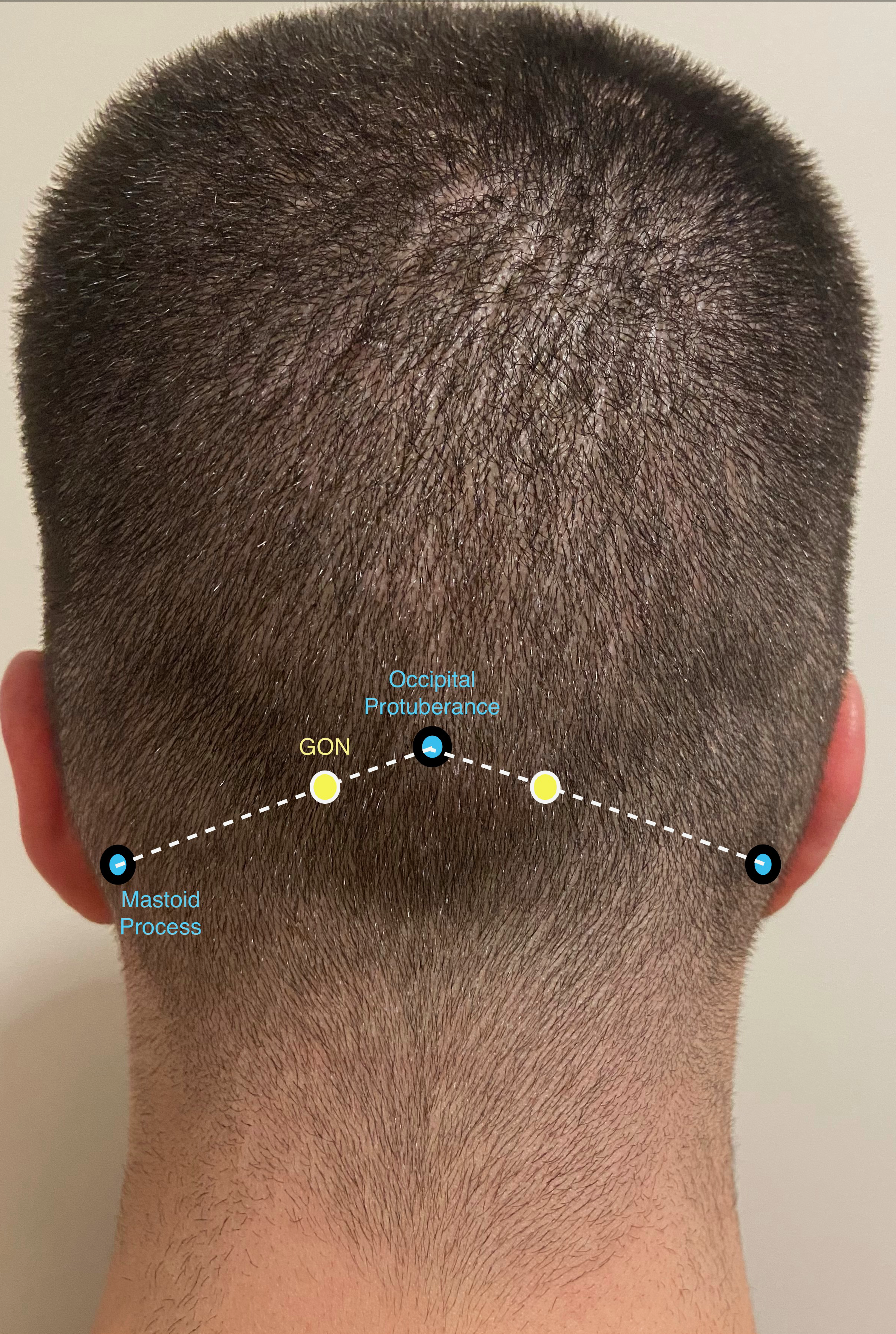

- Palpate the back of the skull to identify the occipital protuberance and the mastoid process on the side of the head where the patient is experiencing the majority of their pain.

- Locate the location of the greater occipital nerve. The location of the GON is approximately one-third of the distance from the occipital protuberance to the mastoid process. This location should be approximately 2 cm inferior and 2 cm lateral from the protuberance.

- Cleanse this area using povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine

- Obtain a syringe filled with the anesthetic. Use an inferior-lateral approach to insert the needle toward the greater occipital nerve. Gently advance the needle tip until resistance is appreciated, indicating contact with the periosteum.

- Withdraw the needle approximately 1 mm and aspirate to ensure the needle is not in contact with the occipital artery.

- Inject anesthetic in fan-like distribution. The provider may also elect to inject anesthetic directly without fanning distribution.

- Withdraw the needle and apply pressure for 5 to 10 minutes.[5]

It should be noted that response to the greater occipital nerve block commonly varies from patient to patient, and the outcome can be difficult to predict. When a GON-block is successful, pain typically improves after 20 to 30 minutes and can last for several hours to several months.

Complications

The greater occipital nerve block is an overall safe procedure. Most side effects are mild and transient. The most commonly encountered side effects include pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site. Other common symptoms after injection can include dizziness, vertigo, numbness, and lightheadedness. Patients may also experience vasovagal syncope, presyncope, facial edema, worsening headache, transient dysphagia, nerve trauma, arterial injury, infection, hematoma, and worsening headache. If a steroid is used, patients may also experience alopecia at the injection site.[5]

Only a small amount of anesthetic is used for the GON-block. However, prevention and early identification of lidocaine toxicity must always be addressed. Additional adverse reactions related to lidocaine or bupivacaine toxicity include methemoglobinemia, hypotension, seizures, and cardiac dysrhythmias. The risk of complications can be reduced by aspirating before injecting an anesthetic and communicating with the patient after the nerve block is completed to identify and address new symptoms.[16]

Clinical Significance

Headache is a common presenting complaint among patients of all age groups and is encountered in multiple medical fields. The disorder is frequently debilitating, can reduce a patient's quality of life, and is associated with a large socioeconomic burden.[2]

The greater occipital nerve block is an effective treatment modality and should be considered in managing acute and chronic headaches. The GON-block procedure can be easily performed with minimal equipment and is an overall safe treatment option, even for patients with multiple comorbidities. The GON-block can be performed singularly or combined with other oral or intravenous pain regimens to increase desirable patient outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing headaches with the greater occipital nerve block requires an interprofessional team that can include a variety of healthcare professionals, including nursing, surgical technicians, physician assistant, and physician. Incorporating a team approach has proven to optimize patient outcomes and prevent adverse reactions. Coordination of care requires communication and participation among team members, including the following:

- Ordering the anesthetic and steroid

- Maintaining patient position and support while the procedure is being performed

- Monitoring the patient for adverse reactions, including signs and symptoms consistent with respiratory compromise, cardiac arrhythmia, and central nervous system depression

- Consulting with a neurologist about further neurological testing and long-term management if required