Introduction

The human tongue is an organ that aids the process of digestion by facilitating the manipulation and movement of food particles during mastication and swallowing. The tongue is also vital in the production of speech and essential for employing the sense of taste.

The styloglossus muscle is a paired extrinsic muscle of the tongue. It coordinates with the other extrinsic muscles of the tongue, including the hyoglossus muscle, the genioglossus muscle, and the palatoglossus muscle, to produce the various movements of the tongue. The styloglossus muscle causes the lateral margins of the tongue to curve upwards, forming a furrow to permit swallowing following mastication of food particles. The paired styloglossus muscles also act to retract and elevate the tongue in a posterior and superior direction.[1]

Structure and Function

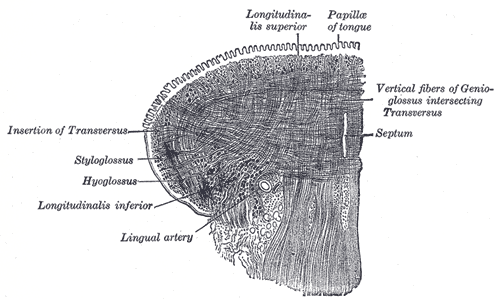

Originating at the apex of the styloid process of the temporal bone, the styloglossus muscle inserts into the lateral aspect of the tongue, namely into the fibers of the intrinsic longitudinal muscles and between the two parts of the hyoglossus muscle. External and internal fibers of the styloglossus muscle also fuse with parts of the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and the palatoglossus muscle, respectively, with three bundles traveling anteriorly towards the apex of the tongue and an inferior longitudinal bundle joining the inferior fibers of the genioglossus muscle.[2]

The fibers of the styloglossus muscle can be divided into anterior and posterior bundles. Anteriorly, the bundles run bilaterally and meet at the midline of the floor of the tongue, forming an arch. The posterior bundles of the styloglossus muscle split into approximately 10 smaller bundles of fibers that enter the tongue. These smaller bundles course between the inferior longitudinal intrinsic muscles of the tongue and the genioglossus muscle and ultimately insert into the lingual septum.[3]

The styloglossus muscle functions to retract and elevate the tongue in a posterior and superior fashion. Following mastication, these movements promote passage of the food bolus towards the oropharynx.[4]

Embryology

Embryologically, the tongue begins to develop approximately within the fourth gestational week, coinciding with the emergence of the pharyngeal arches. Each of the first four pharyngeal arches plays a role in the development of the tongue.[5] The muscle fibers of the tongue form from myoblasts, which are derived from mesodermal occipital somites.[1] Stromal components of the tongue are conversely derived from ectoderm.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

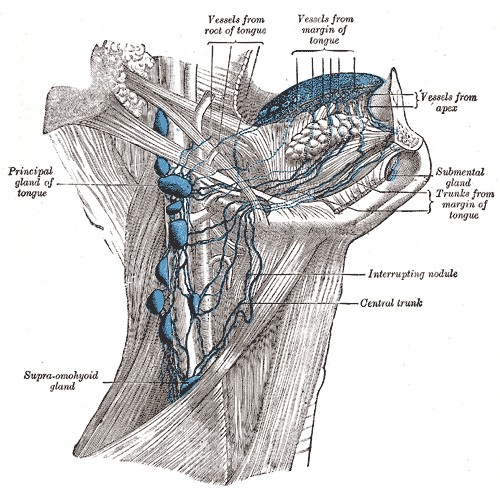

The styloglossus muscle receives its blood supply from the sublingual branch of the lingual artery. The lingual artery is a direct branch of the external carotid artery; it takes off from the external carotid at the level of the greater horn of the hyoid bone[1]. After this, the lingual artery travels between the hyoglossus (superficial) and middle pharyngeal constrictor (deep) to supply blood to the tongue. Dorsal lingual arteries supply the base of the tongue, whereas deep lingual arteries supply the body of the tongue.[7]

Venous drainage of the tongue is via deep lingual veins and a single dorsal lingual vein; these vessels drain into the sublingual vein, which in turn empties directly into the internal jugular vein.

Lymphatic drainage of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is to the submental and submandibular lymph nodes, emptying into the deep cervical chain of lymph nodes. The posterior third of the tongue drains directly into the deep cervical lymph nodes.

Nerves

The intrinsic and extrinsic musculature of the tongue is controlled by the 12th cranial nerve, the hypoglossal nerve, except for the palatoglossus muscle, which is innervated by the 10th cranial nerve, the vagus nerve.[8]

The hypoglossal nerve travels superficially to the hyoglossus muscle. Damage to the hypoglossal nerve results in ipsilateral deviation of the tongue, i.e., damage to the left hypoglossal nerve will cause deviation of the tongue to the left side.

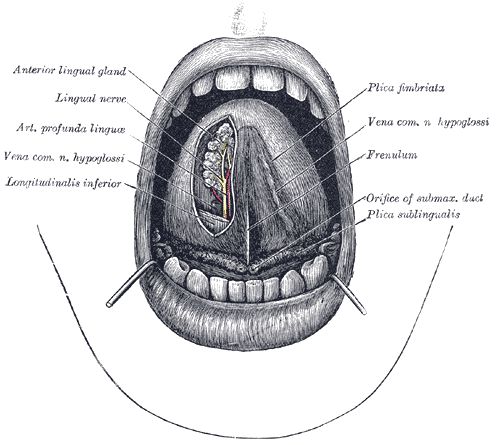

Taste sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue is supplied via the chorda tympani branch of the facial (VII) nerve and the glossopharyngeal (IX) nerve to the posterior one-third; the glossopharyngeal nerve also supplies somatic sensation to the posterior one-third of the tongue. The lingual nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal (V) nerve, supplies somatic sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Muscles

The tongue comprises intrinsic and extrinsic muscles. The intrinsic muscles consist of superior and inferior lingual longitudinal muscles, the transverse lingual muscle, and the vertical lingual muscle. The intrinsic muscles of the tongue act predominantly to alter the shape of the tongue. The extrinsic muscles determine the tongue's movement and position.

There are four sets of paired extrinsic muscles: the styloglossus, hyoglossus, genioglossus, and palatoglossus muscles. The styloglossus muscle acts to lift the lateral edges and to retract the tongue. The hyoglossus muscle causes retraction as well as depression of the tongue. The genioglossus muscle protrudes the tongue. The palatoglossus muscles elevate the posterior part of the tongue. The former three muscles are innervated by the hypoglossal (XII) nerve, whereas the palatoglossus muscle is innervated by the vagus (X) nerve.

Physiologic Variants

The muscles of the tongue function together to permit a variety of shapes and functions to facilitate the production of speech and aid in the process of swallowing and manipulation of food before ingestion. The tongue must elevate posteriorly to push the bolus posteroinferiorly towards the hypopharynx and esophagus to swallow a food bolus efficiently.

There are a number of disorders of the tongue described in the literature. These include but are not limited to:

Ankyloglossia, informally known as “tongue-tie,” caused by an aberrantly short lingual frenulum, is a disorder that may manifest as difficulty with the articulation of words due to restricted manipulation of tongue movements. A surgical procedure to split the lingual frenulum is often undertaken, although many people are able to swallow and articulate normally with a short lingual frenulum. Additionally, in some areas, frenulotomy (also known as frenotomy or frenuloplasty) is performed with increasing frequency, particularly when first-time mothers have difficulty breastfeeding, despite inadequate trials of conservative treatment preoperatively.[9][10][11][12]

A non-malignant condition of the tongue known as migratory glossitis is an asymptomatic disorder in which the dorsum of the tongue produces red patches surrounded by a white peripheral border. This can occur due to general inflammation of the tongue and often results in loss of the lingual papillae on the surface of the tongue.[13]

A fissured tongue features small grooves on the dorsum of the tongue, which are non-tender; this condition has been linked with psoriasis and Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome.[14]

Surgical Considerations

Hypoglossal nerve stimulation is an alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). OSA often occurs due to a lack of tone of the tongue and pharynx within the airway and is frequently exacerbated by large tonsils, nasal obstruction, retrognathia, and adipose deposits in the neck.[15]

It has been postulated that the muscle fibers in the posterior part of the tongue have a higher fatigue tolerance compared to anterior fibers. This explains the ability of the posterior tongue to contract for long periods of time during sleep to prevent upper airway collapse.[15] Neurostimulation of the proximal hypoglossal nerve with the aim of increasing tone in the tongue is an increasingly performed procedure with a high likelihood of success in appropriately selected patients.[16][17][18]

Surgical resection of malignant lesions of the tongue is another major source of tongue muscular dysfunction. The majority of tongue cancers are located on the lateral aspects and the base, the resection of which can alter tongue structure and function. Moreover, the hypoglossal nerve can be damaged in such surgeries, resulting in a malfunction of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue, except for the palatoglossus muscle, which is innervated by the vagus (X) nerve.

In some cases, a small partial glossectomy may cause only limited, temporary tongue weakness, but hemiglossectomies or more extensive resections have a hugely significant impact on patients' quality of life due to reduced ability to speak and swallow. Reconstruction with free soft tissue transfer is often necessary, but while these techniques may provide bulk that improves swallowing and potentially articulation, preoperative function does not generally return after major surgery.

Intraoperatively and preoperatively, the styloglossus muscle can play an important role in characterizing the location of tumors, particularly squamous cell carcinomas, and therefore facilitate staging and accurate prognosis.[19] Invasion of the styloglossus muscle on magnetic resonance imaging has resulted in the up-staging of some tumors that were initially thought to be less aggressive.[20]

Resection of the styloglossus muscle during a transoral approach for squamous cell carcinoma of the lateral oropharynx exposes many vascular structures, and thus a transcervical approach may be preferable. The potential use of the styloglossus muscle in staging for squamous cell cancers of the lateral oropharynx has significant implications for surgical oncology of the head and neck, particularly with respect to conservation of speech and swallowing function.

Clinical Significance

As an extrinsic muscle of the tongue, the styloglossus muscle is innervated by the hypoglossal (XII) nerve. Thus, it is possible to assess the function of the hypoglossal nerve by testing the movements of the tongue. On examination, patients are instructed to protrude the tongue. Damage of the hypoglossal nerve causes ipsilateral deviation of the tongue, i.e., the tongue will deviate to the side of the lesion or injury.

The course of the styloglossus muscle connects the pharyngeal and submandibular spaces, forming the buccopharyngeal gap between the middle and superior constrictor muscles of the pharynx. This explains why a soft tissue infection of the submandibular space may spread to the pharyngeal space and surrounding structures. This spread may lead to extension into the adjacent retropharyngeal spaces; further spread into the thoracic cavity may result in mediastinitis, which is rare but has a high mortality rate.[1]

Ludwig’s angina, a potentially fatal spreading cellulitis of the submandibular, sublingual, and submental spaces, can cause significant swelling of the tongue and retropulsion of the tongue base, threatening the airway.[21] Direct spread of the infection to involve laryngeal structures, such as the epiglottis, can result in edema and airway compromise.

In many ways, the tongue is essential for quality of life and for participating in human society. Without a functional tongue, verbal speech is next to impossible and oral feeding is prohibitively difficult. As an extrinsic muscle, the styloglossus plays an integral role in tongue movement and may improve oral and pharyngeal cancer management.