Introduction

Cardiac muscle also called the myocardium, is one of three major categories of muscles found within the human body, along with smooth muscle and skeletal muscle. Cardiac muscle, like skeletal muscle, is made up of sarcomeres that allow for contractility. However, unlike skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle is under involuntary control.

The heart is made up of three layers—pericardium, myocardium, and endocardium. The endocardium is not cardiac muscle and is comprised of simple squamous epithelial cells and forms the inner lining of the heart chambers and valves. The pericardium is a fibrous sac surrounding the heart, consisting of the epicardium, pericardial space, parietal pericardium, and fibrous pericardium.[1]

The cardiac muscle is responsible for the contractility of the heart and, therefore, the pumping action. The cardiac muscle must contract with enough force and enough blood to supply the metabolic demands of the entire body. This concept is termed cardiac output and is defined as heart rate x stroke volume, which is determined by the contractile forces of the cardiac muscle and the frequency at which they are activated. With a change in metabolic demand comes a change in the contractility of the heart.

Cellular Level

Cardiac muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) are striated, branched, contain many mitochondria, and are under involuntary control. Each myocyte contains a single, centrally located nucleus surrounded by a cell membrane known as the sarcolemma. The sarcolemma of cardiac muscle cells contains voltage-gated calcium channels, specialized ion channels that skeletal muscle does not possess.

Cardiac muscle cells contain branched fibers connected via intercalated discs that contain gap junctions and desmosomes. These interconnections allow the cardiomyocytes to contract together synchronously to enable the heart to work as a pump.[2]

Gap junctions between adjacent cardiomyocytes allow for the propagation of coordinated action potentials from one cell to the next in a phenomenon known as electrical coupling.[3] Cardiac desmosomes are intercellular structures that anchor cardiac muscle fibers together and are vital in maintaining the structural integrity of the heart.[4]

The functional unit of cardiomyocyte contraction is the sarcomere, which consists of thick (myosin) and thin (actin) filaments, the interactions between which form the basis of the sliding filament theory.[5]

The sarcolemma is the cardiomyocyte plasma membrane containing transverse tubules (t-tubules). These t-tubules are highly branched invaginations of the cardiomyocyte sarcolemma that function in excitation-contraction coupling (ECC), action potential initiation and regulation, maintaining the resting membrane potential, and signal transduction. T-tubules regulate the cardiac ECC by concentrating voltage-gated L-type calcium channels and positioning them in close proximity to calcium sense and release channels, ryanodine receptors (RyRs), at the junctional membrane of the sarcoplasmic reticulum.[6]

Development

The development of the heart occurs in various stages. During embryogenesis, the formation of the primitive streak follows the invagination of epiblast cells, indicating the start of gastrulation. Gastrulation divides the embryonic plate, which originally contained two layers between the yolk sac and amniotic cavity, into three germ layers; ecto-, meso-, and endoderm. The mesoderm is situated between the ectoderm and endoderm layers and, during development, spreads laterally and cranially, forming different structures, particularly the heart.[7]

The myocardium begins developing during the second week of gestation in the dorsal mesocardium. After three weeks post-fertilization, the primitive heart begins to develop as a straight tube changing its configuration as time proceeds. This entails folding of the tube, giving rise to bulges that become analogous to the adult heart; truncus arteriosus develops into the aorta and pulmonary artery, bulbus cordis develops into smooth left and right ventricles, primitive ventricle into trabeculated LV/RV, primitive atrium into trabeculated atria and the sinus venosus which develops into the right atrium (sinus venarum) and coronary sinus.[8]

Around the fourth week of development, the heart undergoes a cardiac looping process that establishes the heart's left-sided orientation. This is performed with the help of cilia, a motile structure, and dynein, a protein.[9] If these factors fail to function correctly, dextrocardia will occur, which places the heart on the right side of the chest. This cardiac anomaly is typically seen in Kartagener Syndrome and primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD).[10]

Further developmental changes occur as the heart is shaped into its proper configuration. The heart begins as a single chamber, but four separate chambers are created through the growth of various septa. The muscular ventricular septum originates from the bottom of the ventricle, with a membranous septum forming shortly after, joining with the aortic-pulmonary septum as its twists down and fuses. The endocardial cushions also appear at this time and separate the left and right atria and ventricles. Any structural changes or defects in these processes can lead to congenital heart disorders.

Function

The primary function of cardiac muscle is to pump blood into circulation by generating sufficient force. The mechanism behind each coordinated contraction involves the cardiac muscle and electrical impulses. These contractile functions of the heart require ATP, which can be obtained through various substrates, including fatty acids, carbohydrates, proteins, and ketones. Aerobic production is the core utilization process; however, the heart may use anaerobic processes in a limited capacity.[11]

Mechanism

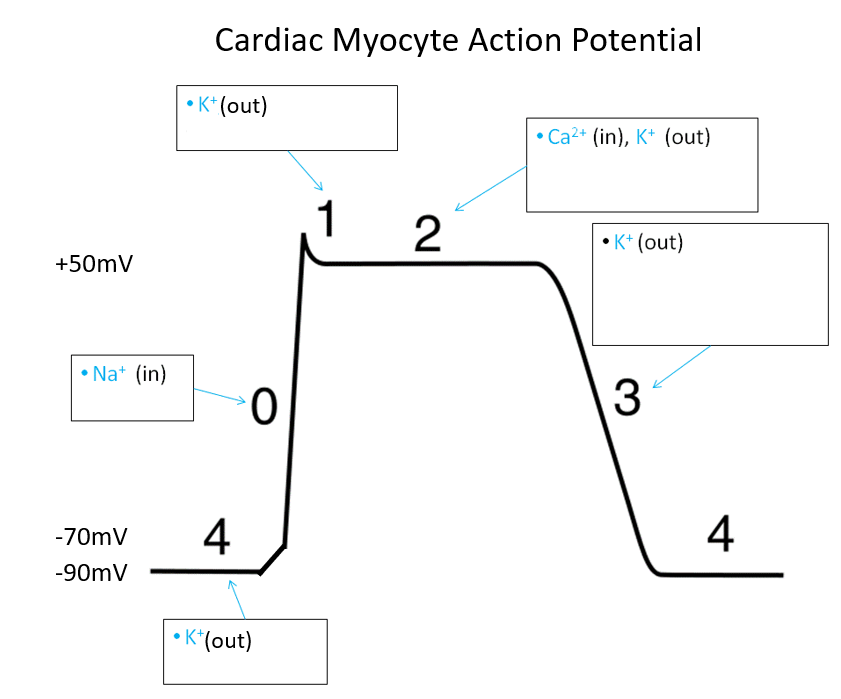

The cardiac action potential lasts approximately 200 ms and is divided into 5 phases: (4) resting, (0) upstroke, (1) early repolarization, (2) plateau, and (3) final repolarization.

Approximate resting membrane potential (RMP): -90 mV

- Phase 4 - RMP due to activity of the Na/K ATPase pump. The exchange of three sodium ions out for two potassium ions in maintains the negative intracellular potential.

- Phase 0 - depolarization to approximately +52 mv due to sodium influx via fast sodium channels

- Phase 1 - partial repolarization due to the closure of fast sodium channels and efflux of potassium and chloride

- Phase 2 - plateau phase maintained by the influx of calcium. Potassium efflux also occurs.

- Phase 3 - repolarization back to RMP due to potassium efflux and closure of sodium and calcium channels

The generation of a cardiac action potential is involuntary and proceeds via a process known as excitation-contraction coupling (ECC). Action potentials travel along the sarcolemma and into the t-tubules to depolarize the membrane. Voltage-sensitive dihydropyridine (DHP) receptors on t-tubules allow calcium influx into the cell via L-type (long-lasting) calcium channels during the plateau phase (phase 2) of the action potential. This increased intracellular calcium concentration triggers the sarcoplasmic reticulum to release more calcium through the ryanodine receptor, known as calcium-induced calcium-released.[12]

The released calcium attaches to troponin C, causing tropomyosin to detach from the myosin-binding sites on actin. Actin and myosin then form a cross-bridge, and contraction occurs. Cross bridges last as long as calcium is attached to troponin.[13]

Lusitropy is the term used to define the relaxation of the myocardium following ECC. Lusitropy is mediated by the SERCA (sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase) pump, which sequesters calcium into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, allowing calcium to be removed from troponin-C and returning the myocardium to its relaxed state.[14]

Unlike the cardiac muscle cells, the pacemaker cells' action potential is divided into 3 phases instead of 5, as phases 1 and 2 are absent. Pacemaker cells are comprised of sinoatrial (SA) and atrioventricular (AV) nodes, which are known to fire spontaneously, sending electrical activity throughout the heart, and do not require stimulation to initiate their action.

This autorhythmicity transpires because of funny current channels, which allow sodium ions to leak continuously into the cell (Phase 4), slowly raising the membrane potential until a certain threshold is reached, causing depolarization of the cell. This subsequently opens calcium channels causing calcium ions to enter the cell, further raising the membrane potential (Phase 0). After a positive membrane potential is sensed, potassium channels open, causing an outward flow of ions, returning the membrane potential to its resting potential (Phase 3).[15]

Related Testing

Many clinical tests are utilized to evaluate the function of cardiac muscle. This list discusses high-yield clinical testing and is not meant to be exhaustive.

Echocardiogram: an ultrasound of the heart routinely used to identify cardiac abnormalities. An echocardiogram can assess valvular abnormalities, masses, pericardial disease, congenital abnormalities, and pulmonary hypertension. An echo is also routinely utilized to assess cardiac muscle function and is useful in diagnosing congestive heart failure and cardiomyopathies. An echocardiogram can be performed as a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) or a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE).

- TTE: a non-invasive test that utilizes an echocardiography probe placed on the chest wall.

- TEE: a specialized probe with an ultrasound transducer at the tip passed into the patient's esophagus, allowing for a posterior view of the heart.

Echocardiogram reports are detailed and offer essential information regarding the heart's function. Echo reports typically include:

- Rate and rhythm

- Chamber size

- Indications of hypertrophy

- Right ventricular function

- Left ventricular systolic function and ejection fraction

- Left ventricular diastolic function

- Valvular pathology (if any)

- Evidence of mass or thrombus

- Congenital abnormalities

- Pericardial anomalies

- Incidental findings[16]

Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG): an EKG is a non-invasive test that utilizes electrodes placed on the body's surface to record the heart's electrical rhythms. These electrical rhythms cause depolarization of the heart, which, in turn, leads to the contraction of the myocardium. With this knowledge, one can understand that the EKG indirectly indicates the heart's contraction.[17]

Cardiac biomarkers: blood tests may be performed to identify enzymes and proteins that can indicate heart disease or cardiac damage.

- Troponin: measures the levels of cardiac proteins troponin T and troponin I. These proteins are found in cardiac muscle and are released upon damage to cardiac muscle, with troponin I being the more sensitive and specific marker of cardiac injury.[18]

- Creatine kinase (CK): This enzyme is released from cardiac and skeletal muscle following damage. The isozyme CK-MB is more sensitive in diagnosing heart damage after a heart attack, with CK-MB levels rising 4 to 6 hours after a heart attack, peaking at 24 hours, and returning to baseline in 48 to 72 hours.[19]

- Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP): a hormone secreted by the ventricular myocardium in response to ventricular wall stress (ie, pressure overload or volume expansion). The gold standard in diagnosing heart failure is the measurement of BNP levels, with an elevated level indicating heart failure.[20]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of cardiac muscle is based on damage to cardiac muscle cells, leading to inappropriate contractility.

Cardiomyopathy: A cardiomyopathy is a genetic or acquired disorder of the myocardium associated with cardiac dysfunction. According to the World Health Organization, there exist five main categories of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy: dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), and unclassified cardiomyopathies.

- Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM): This condition is dilation and impaired contraction of one or both ventricles that cannot be explained by coronary artery disease, valvular disease, or hypertension. Patients with DCM present with decreased systolic contraction and symptoms of heart failure. Inherited forms of DCM have shown mutations in at least 40 individual genes, many of which encode structural components of the sarcomere and desmosome.[21] Nongenetic causes of DCM occur, most often from viral infections leading to inflammation of the myocardium. In addition, certain medications, toxins or allergens, or systemic autoimmune diseases may lead to DCM.[22]

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM): This condition is an autosomal dominant disease leading to a thickened (hypertrophied) left ventricle and abnormal heart contraction caused by a mutation in the sarcomere protein genes. This hypertrophied left ventricle leads to outflow obstruction, diastolic dysfunction, mitral regurgitation, and myocardial ischemia. In severe cases, sudden cardiac death may occur.[23]

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM): This condition results in impaired ventricular filling in the setting of nondilated ventricles. RCM is typically characterized by nondilated nonhypertrophied ventricles, with biatrial enlargement secondary to increased atrial pressures. Diseases in which RCM may be seen include sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, and hemochromatosis.[24]

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC): This is the replacement of the myocardium with fibrofatty tissue leading to an increased predisposition to ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death, especially in young adults and athletes. The release of exercise-induced catecholamines provokes ventricular arrhythmias in predisposed individuals. ARVM typically affects the right ventricle.[25]

- Unclassified cardiomyopathies:

- Stress-induced cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy): A condition known as "broken heart syndrome" presents as a reversible transient ballooning of the apex of the left ventricle leading to wall motion abnormalities brought on by severe emotional or physical stress.[26]

- Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: This is a condition of diastolic and systolic dysfunction, impaired cardiac response to stress, and ECG abnormalities (QT prolongation) in patients with cirrhosis. Cardiac function is typically altered only under stressful conditions.[27]

- Ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) is a form of dilated cardiomyopathy related to coronary artery disease (CAD). ICM is the decreased ability of the heart to properly pump blood throughout the body due to myocardial damage from cardiac ischemia. The lack of blood supply to the cardiomyocytes leads to cell death, cardiac fibrosis, and left ventricular enlargement and dilation.[28] Globally, ischemic heart disease (IHD) is the leading cause of death, with approximately 7.2 million deaths yearly.[29]

Heart Failure: impairment of ventricular filling and systolic ejection of blood due to structural and functional defects of the myocardium. The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is crucial in the specific assessment of heart failure. A heart failure patient with an ejection fraction (EF) greater than or equal to 50% is diagnosed as having heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

An ejection fraction less than or equal to 40% is termed heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and an ejection fraction of 41 to 49% is diagnosed as heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF). Distinguishing between these three types of heart failure is of clinical importance, as each has specific treatments and medications.[30]

Myocarditis: an inflammatory disease of the myocardium most commonly caused by acute rheumatic fever or viral infections (Coxsackie virus, parvovirus B19). The long-term outcome of untreated myocarditis is dilated cardiomyopathy with heart failure.[31]

Clinical Significance

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in both men and women in the United States and worldwide.[29] The clinical care of patients with heart disease is based on assessing myocardial function and using interventions to improve cardiac muscle performance and prevent myocardial maladaptations. Based on the pathophysiology previously mentioned, treatment modalities will vary from patient to patient.

As heart failure is seen worldwide, clinicians must understand the physiology and management of this disease. Symptomatic heart failure is typically managed with vasodilators, diuretics, positive inotropes, or digoxin. The ideal therapy would include a diuretic and a vasodilator, such as an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or hydralazine plus isosorbide dinitrate. Depending on the patient's presentation, this therapy would occur with or without digoxin.[32]

Clinicians must talk with each patient about the importance of cardiovascular health. Simply put, the stronger the heart muscles are, the more efficient they become. Regular aerobic exercise is of great importance in the overall health of cardiac muscles and helps strengthen muscle tissue, lowering the risk of stroke and heart attack. Aerobic exercise includes running or walking, swimming, cycling, dancing, and climbing stairs.