[1]

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20:303(3):235-41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. Epub 2010 Jan 13

[PubMed PMID: 20071471]

[2]

Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991-1998. JAMA. 1999 Oct 27:282(16):1519-22

[PubMed PMID: 10546690]

[3]

Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, Farzadfar F, Riley LM, Ezzati M, Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index). National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. Lancet (London, England). 2011 Feb 12:377(9765):557-67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. Epub 2011 Feb 3

[PubMed PMID: 21295846]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[4]

Henry FJ. Obesity prevention: the key to non-communicable disease control. The West Indian medical journal. 2011 Jul:60(4):446-51

[PubMed PMID: 22097676]

[5]

Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity-related non-communicable diseases: South Asians vs White Caucasians. International journal of obesity (2005). 2011 Feb:35(2):167-87. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.135. Epub 2010 Jul 20

[PubMed PMID: 20644557]

[6]

Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al Mamun A, Bonneux L, NEDCOM, the Netherlands Epidemiology and Demography Compression of Morbidity Research Group. Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2003 Jan 7:138(1):24-32

[PubMed PMID: 12513041]

[7]

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992 Jun:30(6):473-83

[PubMed PMID: 1593914]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

Fontaine KR, Cheskin LJ, Barofsky I. Health-related quality of life in obese persons seeking treatment. The Journal of family practice. 1996 Sep:43(3):265-70

[PubMed PMID: 8797754]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[9]

Richards MM, Adams TD, Hunt SC. Functional status and emotional well-being, dietary intake, and physical activity of severely obese subjects. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2000 Jan:100(1):67-75

[PubMed PMID: 10646007]

[10]

Doll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL. Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obesity research. 2000 Mar:8(2):160-70

[PubMed PMID: 10757202]

[11]

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Sjöström L, Backman L, Bengtsson C, Bouchard C, Dahlgren S, Jonsson E, Larsson B, Lindstedt S. Swedish obese subjects (SOS)--an intervention study of obesity. Baseline evaluation of health and psychosocial functioning in the first 1743 subjects examined. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1993 Sep:17(9):503-12

[PubMed PMID: 8220652]

[13]

GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Sep 16:390(10100):1151-1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28919116]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[14]

Nyberg ST, Batty GD, Pentti J, Virtanen M, Alfredsson L, Fransson EI, Goldberg M, Heikkilä K, Jokela M, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Lallukka T, Leineweber C, Lindbohm JV, Madsen IEH, Magnusson Hanson LL, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pietiläinen O, Rahkonen O, Rugulies R, Shipley MJ, Stenholm S, Suominen S, Theorell T, Vahtera J, Westerholm PJM, Westerlund H, Zins M, Hamer M, Singh-Manoux A, Bell JA, Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M. Obesity and loss of disease-free years owing to major non-communicable diseases: a multicohort study. The Lancet. Public health. 2018 Oct:3(10):e490-e497. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30139-7. Epub 2018 Sep 1

[PubMed PMID: 30177479]

[15]

Flint SW, Čadek M, Codreanu SC, Ivić V, Zomer C, Gomoiu A. Obesity Discrimination in the Recruitment Process: "You're Not Hired!". Frontiers in psychology. 2016:7():647. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00647. Epub 2016 May 3

[PubMed PMID: 27199869]

[16]

Tunceli K, Li K, Williams LK. Long-term effects of obesity on employment and work limitations among U.S. Adults, 1986 to 1999. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2006 Sep:14(9):1637-46

[PubMed PMID: 17030975]

[17]

Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2009 Sep-Oct:28(5):w822-31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. Epub 2009 Jul 27

[PubMed PMID: 19635784]

[18]

Spieker EA, Pyzocha N. Economic Impact of Obesity. Primary care. 2016 Mar:43(1):83-95, viii-ix. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.013. Epub 2016 Jan 12

[PubMed PMID: 26896202]

[19]

Pajak A, Topór-Madry R, Waśkiewicz A, Sygnowska E. Body mass index and risk of death in middle-aged men and women in Poland. Results of POL-MONICA cohort study. Kardiologia polska. 2005 Feb:62(2):95-105; discussion 106-7

[PubMed PMID: 15815793]

[20]

Ferrante JM, Ohman-Strickland P, Hudson SV, Hahn KA, Scott JG, Crabtree BF. Colorectal cancer screening among obese versus non-obese patients in primary care practices. Cancer detection and prevention. 2006:30(5):459-65

[PubMed PMID: 17067753]

[21]

Mitchell RS, Padwal RS, Chuck AW, Klarenbach SW. Cancer screening among the overweight and obese in Canada. American journal of preventive medicine. 2008 Aug:35(2):127-32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.031. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18617081]

[22]

Amy NK, Aalborg A, Lyons P, Keranen L. Barriers to routine gynecological cancer screening for White and African-American obese women. International journal of obesity (2005). 2006 Jan:30(1):147-55

[PubMed PMID: 16231037]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[24]

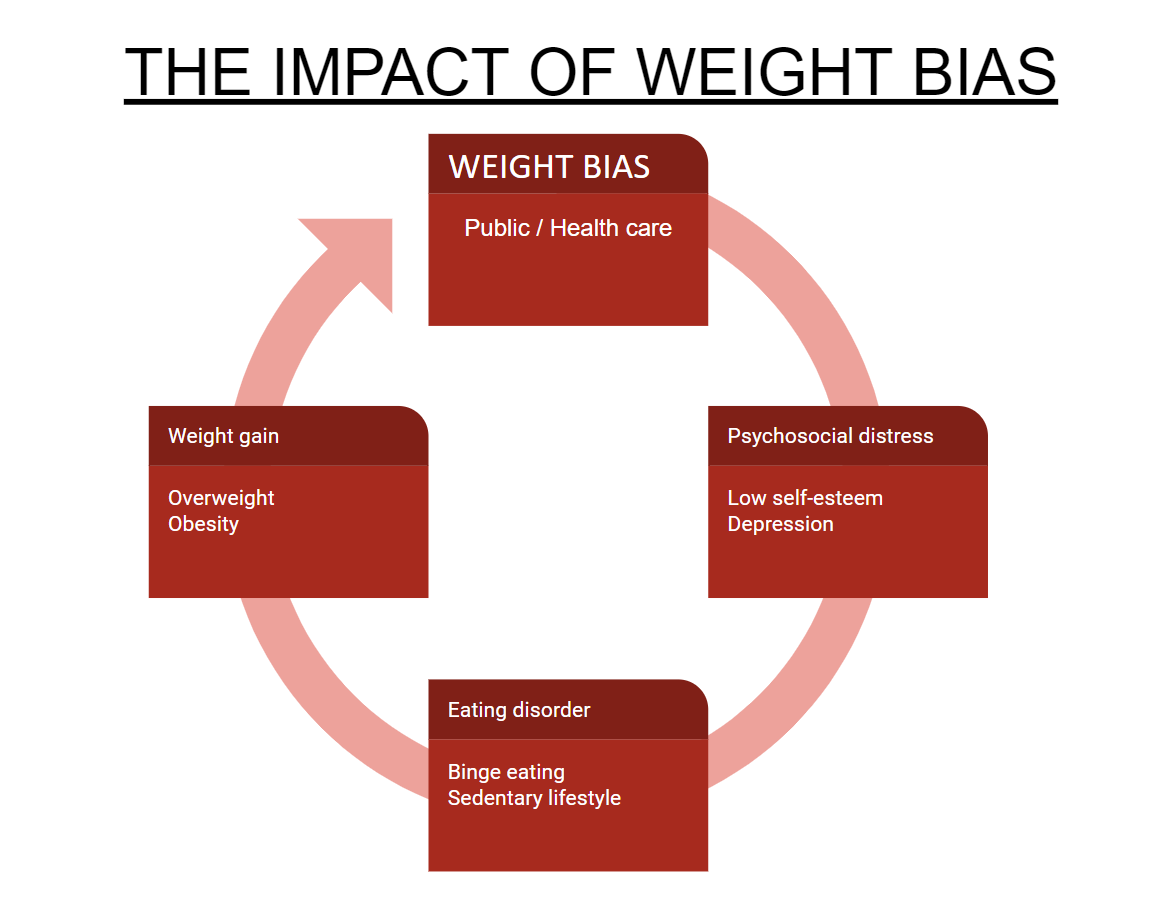

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. American journal of public health. 2010 Jun:100(6):1019-28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491. Epub 2010 Jan 14

[PubMed PMID: 20075322]

[25]

Davis B, Carpenter C. Proximity of fast-food restaurants to schools and adolescent obesity. American journal of public health. 2009 Mar:99(3):505-10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137638. Epub 2008 Dec 23

[PubMed PMID: 19106421]

[26]

Zhang Q, Liu S, Liu R, Xue H, Wang Y. Food Policy Approaches to Obesity Prevention: An International Perspective. Current obesity reports. 2014 Jun:3(2):171-82. doi: 10.1007/s13679-014-0099-6. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25705571]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[27]

Larsen TM, Dalskov S, van Baak M, Jebb S, Kafatos A, Pfeiffer A, Martinez JA, Handjieva-Darlenska T, Kunesová M, Holst C, Saris WH, Astrup A. The Diet, Obesity and Genes (Diogenes) Dietary Study in eight European countries - a comprehensive design for long-term intervention. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2010 Jan:11(1):76-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00603.x. Epub 2009 May 28

[PubMed PMID: 19470086]

[28]

McMillan-Price J, Petocz P, Atkinson F, O'neill K, Samman S, Steinbeck K, Caterson I, Brand-Miller J. Comparison of 4 diets of varying glycemic load on weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in overweight and obese young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2006 Jul 24:166(14):1466-75

[PubMed PMID: 16864756]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[29]

Brown RD. The traffic light diet can lower risk for obesity and diabetes. NASN school nurse (Print). 2011 May:26(3):152-4

[PubMed PMID: 21675296]

[30]

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Sanderson RS, Allison DB, Kessler A. Primary care physicians' attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obesity research. 2003 Oct:11(10):1168-77

[PubMed PMID: 14569041]