[1]

Anantham D, Koh MS, Ernst A. Endobronchial ultrasound. Respiratory medicine. 2009 Oct:103(10):1406-14. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.04.010. Epub 2009 May 15

[PubMed PMID: 19447014]

[2]

Steinfort DP, Khor YH, Manser RL, Irving LB. Radial probe endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. The European respiratory journal. 2011 Apr:37(4):902-10. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00075310. Epub 2010 Aug 6

[PubMed PMID: 20693253]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[3]

VanderLaan PA, Wang HH, Majid A, Folch E. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA): an overview and update for the cytopathologist. Cancer cytopathology. 2014 Aug:122(8):561-76. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21431. Epub 2014 Apr 23

[PubMed PMID: 24760496]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[4]

Herth F, Becker HD, LoCicero J 3rd, Ernst A. Endobronchial ultrasound in therapeutic bronchoscopy. The European respiratory journal. 2002 Jul:20(1):118-21

[PubMed PMID: 12171063]

[5]

Figueiredo VR, Cardoso PFG, Jacomelli M, Santos LM, Minata M, Terra RM. EBUS-TBNA versus surgical mediastinoscopy for mediastinal lymph node staging in potentially operable non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jornal brasileiro de pneumologia : publicacao oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisilogia. 2020:46(6):e20190221. doi: 10.36416/1806-3756/e20190221. Epub 2020 Oct 23

[PubMed PMID: 33111752]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[6]

Avasarala SK, Aravena C, Almeida FA. Convex probe endobronchial ultrasound: historical, contemporary, and cutting-edge applications. Journal of thoracic disease. 2020 Mar:12(3):1085-1099. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.10.76. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32274177]

[7]

Sheski FD, Mathur PN. Endobronchial ultrasound. Chest. 2008 Jan:133(1):264-70. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1735. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18187751]

[8]

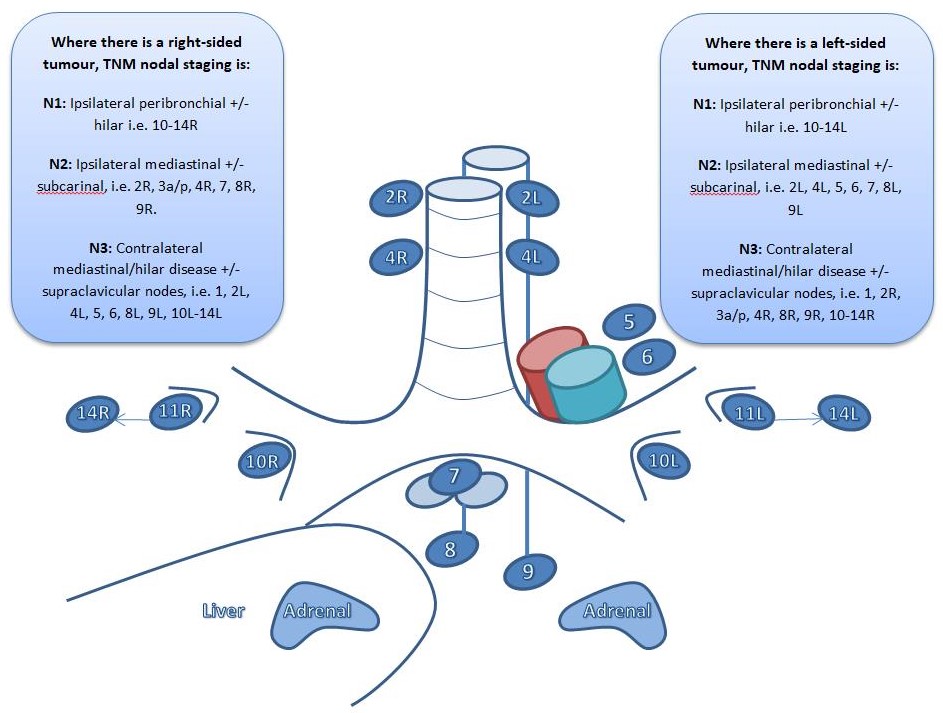

Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, Giroux DJ, Rami-Porta R, Goldstraw P, Members of IASLC Staging Committee. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2009 May:4(5):568-77. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a0d82e. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19357537]

[9]

Sampsonas F, Kakoullis L, Lykouras D, Karkoulias K, Spiropoulos K. EBUS: Faster, cheaper and most effective in lung cancer staging. International journal of clinical practice. 2018 Feb:72(2):. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13053. Epub 2018 Jan 3

[PubMed PMID: 29314425]

[10]

Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WE, Nicholson AG, Groome P, Mitchell A, Bolejack V, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee, Advisory Boards, and Participating Institutions, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging and Prognostic Factors Committee Advisory Boards and Participating Institutions. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2016 Jan:11(1):39-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26762738]

[11]

Furlow PW, Mathisen DJ. Surgical anatomy of the trachea. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2018 Mar:7(2):255-260. doi: 10.21037/acs.2018.03.01. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29707503]

[12]

Fielding DI, Kurimoto N. EBUS-TBNA/staging of lung cancer. Clinics in chest medicine. 2013 Sep:34(3):385-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.06.003. Epub 2013 Jul 12

[PubMed PMID: 23993811]

[13]

Crombag LMM, Mooij-Kalverda K, Szlubowski A, Gnass M, Tournoy KG, Sun J, Oki M, Ninaber MK, Steinfort DP, Jennings BR, Liberman M, Bilaceroglu S, Bonta PI, Korevaar DA, Trisolini R, Annema JT. EBUS versus EUS-B for diagnosing sarcoidosis: The International Sarcoidosis Assessment (ISA) randomized clinical trial. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 2022 Feb:27(2):152-160. doi: 10.1111/resp.14182. Epub 2021 Nov 17

[PubMed PMID: 34792268]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[14]

Erer OF, Erol S, Anar C, Biçmen C, Aydoğdu Z, Aktoğu S. The diagnostic accuracy of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) in mediastinal tuberculous lymphadenitis. Turkish journal of medical sciences. 2017 Dec 19:47(6):1874-1879. doi: 10.3906/sag-1606-110. Epub 2017 Dec 19

[PubMed PMID: 29306252]

[15]

Navasakulpong A, Auger M, Gonzalez AV. Yield of EBUS-TBNA for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis: impact of operator and cytopathologist experience. BMJ open respiratory research. 2016:3(1):e000144. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2016-000144. Epub 2016 Aug 9

[PubMed PMID: 27547408]

[16]

Navani N, Molyneaux PL, Breen RA, Connell DW, Jepson A, Nankivell M, Brown JM, Morris-Jones S, Ng B, Wickremasinghe M, Lalvani A, Rintoul RC, Santis G, Kon OM, Janes SM. Utility of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in patients with tuberculous intrathoracic lymphadenopathy: a multicentre study. Thorax. 2011 Oct:66(10):889-93. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200063. Epub 2011 Aug 3

[PubMed PMID: 21813622]

[17]

Du Rand IA, Barber PV, Goldring J, Lewis RA, Mandal S, Munavvar M, Rintoul RC, Shah PL, Singh S, Slade MG, Woolley A, British Thoracic Society Interventional Bronchoscopy Guideline Group. British Thoracic Society guideline for advanced diagnostic and therapeutic flexible bronchoscopy in adults. Thorax. 2011 Nov:66 Suppl 3():iii1-21. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200713. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21987439]

[18]

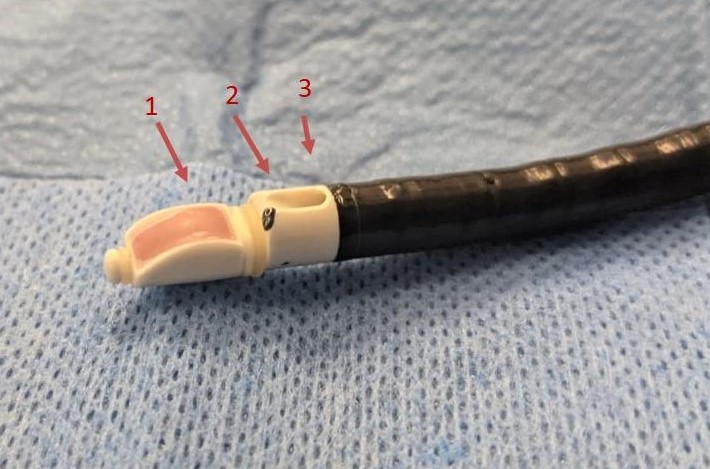

Delage A, Beaudoin S. Technical Aspects of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration. Chest. 2016 Jul:150(1):255. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.063. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27396786]

[19]

Erer OF, Erol S, Anar C, Aydoğdu Z, Özkan SA. Diagnostic yield of EBUS-TBNA for lymphoma and review of the literature. Endoscopic ultrasound. 2017 Sep-Oct:6(5):317-322. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.180762. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27121291]

[20]

Santos RS, Raftopoulos Y, Keenan RJ, Halal A, Maley RH, Landreneau RJ. Bronchoscopic palliation of primary lung cancer: single or multimodality therapy? Surgical endoscopy. 2004 Jun:18(6):931-6

[PubMed PMID: 15108108]

[21]

Eom JS, Mok JH, Kim I, Lee MK, Lee G, Park H, Lee JW, Jeong YJ, Kim WY, Jo EJ, Kim MH, Lee K, Kim KU, Park HK. Radial probe endobronchial ultrasound using a guide sheath for peripheral lung lesions in beginners. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2018 Aug 13:18(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0704-7. Epub 2018 Aug 13

[PubMed PMID: 30103727]

[22]

British Thoracic Society Bronchoscopy Guidelines Committee, a Subcommittee of Standards of Care Committee of British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society guidelines on diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy. Thorax. 2001 Mar:56 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i1-21

[PubMed PMID: 11158709]

[23]

Jalil BA, Yasufuku K, Khan AM. Uses, limitations, and complications of endobronchial ultrasound. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2015 Jul:28(3):325-30

[PubMed PMID: 26130878]

[24]

Muthu V, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Prasad KT, Gupta N, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R. Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration: Techniques and Challenges. Journal of cytology. 2019 Jan-Mar:36(1):65-70. doi: 10.4103/JOC.JOC_171_18. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30745744]

[25]

Casal RF, Lazarus DR, Kuhl K, Nogueras-González G, Perusich S, Green LK, Ost DE, Sarkiss M, Jimenez CA, Eapen GA, Morice RC, Cornwell L, Austria S, Sharafkanneh A, Rumbaut RE, Grosu H, Kheradmand F. Randomized trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration under general anesthesia versus moderate sedation. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2015 Apr 1:191(7):796-803. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1615OC. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25574801]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[26]

Argento AC, Puchalski J. Convex probe EBUS for centrally located parenchymal lesions without a bronchus sign. Respiratory medicine. 2016 Jul:116():55-8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.04.012. Epub 2016 Apr 29

[PubMed PMID: 27296821]

[27]

Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R. Impact of Rapid On-Site Cytological Evaluation (ROSE) on the Diagnostic Yield of Transbronchial Needle Aspiration During Mediastinal Lymph Node Sampling: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chest. 2018 Apr:153(4):929-938. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.11.004. Epub 2017 Nov 15

[PubMed PMID: 29154972]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[28]

Sehgal IS, Gupta N, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Madan K, Jain D, Gupta P, Madan NK, Rajwanshi A, Agarwal R. Processing and Reporting of Cytology Specimens from Mediastinal Lymph Nodes Collected using Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration: A State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of cytology. 2020 Apr-Jun:37(2):72-81. doi: 10.4103/JOC.JOC_100_19. Epub 2020 Apr 2

[PubMed PMID: 32606494]

[29]

Vaidya PJ, Munavvar M, Leuppi JD, Mehta AC, Chhajed PN. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: Safe as it sounds. Respirology (Carlton, Vic.). 2017 Aug:22(6):1093-1101. doi: 10.1111/resp.13094. Epub 2017 Jun 20

[PubMed PMID: 28631863]

[30]

Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, Okada Y, Sasada S, Sato S, Suzuki E, Semba H, Fukuoka K, Fujino S, Ohmori K. Complications associated with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a nationwide survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy. Respiratory research. 2013 May 10:14(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-50. Epub 2013 May 10

[PubMed PMID: 23663438]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[31]

Webb TN, Flenaugh E, Martin R, Parks C, Bechara RI. Effect of Routine Clopidogrel Use on Bleeding Complications After Endobronchial Ultrasound-guided Fine Needle Aspiration. Journal of bronchology & interventional pulmonology. 2019 Jan:26(1):10-14. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0000000000000493. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29664760]

[32]

Sakr L, Dutau H. Massive hemoptysis: an update on the role of bronchoscopy in diagnosis and management. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2010:80(1):38-58. doi: 10.1159/000274492. Epub 2010 Jan 8

[PubMed PMID: 20090288]

[33]

Dong X, Qiu X, Liu Q, Jia J. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in the mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013 Oct:96(4):1502-1507. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.016. Epub 2013 Aug 28

[PubMed PMID: 23993894]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[34]

Agarwal R, Srinivasan A, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. Efficacy and safety of convex probe EBUS-TBNA in sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respiratory medicine. 2012 Jun:106(6):883-92. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.02.014. Epub 2012 Mar 13

[PubMed PMID: 22417738]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence