Continuing Education Activity

Hypopharyngeal cancers are an uncommon type of head and neck cancers and are associated with worse prognosis compared to cancers from other head and neck sites. Alcohol and tobacco use are known risk factors, and a majority of the patients present at an advanced stage. This activity reviews the risk factors for hypopharyngeal cancers, outlines the staging and treatment of the disease, and explores the interprofessional team's role in the management of the patient.

Objectives:

Summarize the risk factors for the formation of hypopharyngeal cancer.

Describe the frequent presentations of hypopharyngeal cancer.

Review the diagnostic process and imaging modalities used in hypopharyngeal cancer.

Outline some interprofessional team strategies that can result in better care coordination for patients presenting with hypopharyngeal cancer.

Introduction

Hypopharyngeal cancer describes tumors arising between the oropharynx and the esophageal inlet, more precisely defined as between the level of the hyoid bone and the lower end of the cricoid cartilage, respectively. This group of cancers is further subdivided based on the anatomical locations within this area, namely post cricoid (the pharyngoesophageal junction), the piriform sinus, and the posterior pharyngeal wall. Hypopharyngeal cancers do not include carcinoma of the larynx as these are anatomically, pathologically, and therapeutically distinct.[1]

Squamous cell carcinoma arising from the mucosal layer is the most common histology identified in 95% of the cases, while adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, and non-epidermoid carcinoma account for the remaining cases.[2] Tumors of the hypopharynx are characterized by local invasion and lymphatic spread, with 70% of patients presenting with lymph node involvement at the time of diagnosis.[1][3]

Symptomatic burden from hypopharyngeal cancer is determined by the size and location of the primary tumor. Pain, bleeding, and dysphagia are the most common presenting complaints, with concomitant malnutrition a poor prognostic factor. Advanced tumors may invade the larynx giving features of airway compromise and aspiration. Surgical management requiring a combination of partial or total pharyngectomy and laryngectomy dependent on site and stage at presentation can lead to significant functional morbidity.[4]

Hypopharyngeal cancer has an annual incidence of approximately 3,000 cases per year in the United States, accounting for around 7% of upper aerodigestive tract cancers. The prognosis is often worse due to the advanced stage commonly seen at presentation while considerably rarer than laryngeal cancer. The rate of nodal involvement and metastasis is high at diagnosis, with 50% to 70% of patients presenting with N1 disease or worse. Prognosis in hypopharyngeal cancer is dictated by stage with early disease (T1-T2) having a 60% 5-year survival compared with less than 25% in larger tumors (T3-T4) or those with multiple nodal spread.[5][6]

Etiology

As a primarily squamous cell carcinoma, hypopharyngeal cancer has a similar list of etiological causes to other head and neck cancers. These are the prolonged use of alcohol and tobacco, which act synergistically to potentiate each-others carcinogenic potential. Patients are typically male aged older than 50 with documented alcohol and tobacco usage.

Other risk factors for hypopharyngeal cancer include:

- Plummer-Vinson syndrome: also known as sideropenic dysphagia, this syndrome is characterized by iron deficiency anemia, post-cricoid dysphagia, and high oesophageal webs seen primarily in premenopausal women. It significantly increases the risks of developing post-cricoid cancers and is a recognized cause of hypopharyngeal cancers in women below the age of 50 with iron deficiency anemia.[7]

- The contribution of asbestos to the formation of hypopharyngeal cancers is unclear, but it is considered an independent risk factor as with many other malignancies.[8]

- Unlike cancers of the oral cavity and oropharynx, the human papillomavirus (HPV) is not thought to be a significant risk factor for hypopharyngeal cancers.[9]

- As with esophageal carcinoma, recurrent irritation from gastric content reflux is recognized to contribute to tumor formation in the post-cricoid region much in the same process of metaplasia to dysplasia as is seen in Barret’s esophagus.[10]

- The habitual chewing of the areca (also known as betel) nut, as is commonplace in South and Southeast Asia and East Africa, is strongly associated with tumors in the hypopharynx.[11]

Epidemiology

Hypopharyngeal cancers are uncommon and account for about 80,000 new cases or 0.4% of all new cancers worldwide and around 35000 cancer-related deaths, 0.4% of all cancer-related mortality.[12] Overall, the global incidence of hypopharyngeal cancer is 0.8 per 100,000 (0.3 in women and 1.4 in men).[13] Incidence of hypopharyngeal cancer varies by region, with the highest incidence in South-Central Asia, followed by Central and Eastern Europe, Western Europe, and North America.[12]

The South-Central Asian region has hypopharyngeal cancer as a proportion of head and neck cancers at 17.3% compared with 7.1% in Northern America, 11.3% to 12.8% across Europe, and 7.3% in Latin America.[14][13] In the United States, around 2500, hypopharyngeal cancers are diagnosed each year and account for about 3 to 5% of all head and neck cancers.[15][3] The variation in distribution internationally is most likely attributed to social practices regarding the consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and the chewing of carcinogenic substances.

Pathophysiology

The vast majority (95%) of hypopharyngeal tumors are squamous cell carcinomas, with two-thirds being of the keratinizing variant.[2] Other tumor types include lymphoma, sarcoma, and adenocarcinoma. They are almost always poorly differentiated and aggressive. The majority (70%) of tumors originate in the pyriform sinus, with around a quarter in the posterior pharyngeal wall and the remaining 5% in the post-cricoid region.[16][17]

The location within the pyriform sinus dictates the pattern of spread, with those on the medial wall typically spreading along the mucosa, invading the larynx via the paraglottic gutter. Whereas lateral wall and apex tumors invade into the thyroid cartilage.[18]

History and Physical

Unlike other head and neck cancers, hypopharyngeal cancers develop in less space-critical areas; thus, the impact from a growing lesion is not appreciated until the tumor is considerably large. Therefore they tend to be more advanced at the time of presentation. Early symptoms include a sensation of a lump or discomfort in the throat, painful swallowing, or pain referred to the middle ear. Nodal metastasis occurs relatively early, so the first presentation may be that of a new neck lump. As many as 70% of patients will have an affected lymph node at the time of presentation of the piriform sinus.[19] The patient may experience progressive dysphagia as the tumor becomes more advanced, first affecting the ability to swallow solids than fluids. Hoarseness of voice may occur as the tumor invades into the larynx or by a vocal cord paralysis.[3]

Examining all suspected head and neck cancers follows the same routine to review all areas of concern systematically.

Inspection of the oral cavity will not be able to visualize a primary hypopharyngeal tumor. Still, it could detect a synchronous oral mucosal or oropharyngeal malignancy or perhaps detect invasion into palatopharyngeus muscle as evidenced by the asymmetry in the tonsillar pillars. Advanced tumors will lead to the pooling of secretions or saliva, which may also be seen orally.

Examination of the neck is important as the nodal spread is early.[20] All the cervical lymph nodes should be examined and documented with particular attention to those in level III and IV and the supraclavicular region. Laryngeal rocking feeling for the loss of normal crepitus indicates a substantial post-cricoid lesion or invasion into the prevertebral tissues.

Fiber-optic examination of the hypopharynx and larynx often proves the most fruitful in detecting pyriform sinus posterior pharyngeal or post-cricoid tumors. Indicative signs include the pooling of secretions or asymmetry in the lie of the larynx. Comment should be made on the presence of ulcerated or erythematous mucosal lesions, and hyperkeratosis, and the symmetry and mobility of the vocal cords.

Examination of the cranial nerves may reveal a lesion in the glossopharyngeal or vagus nerves indicating tumor invasion. General examination of the patient may show distant metastatic spread or change to the patient’s constitution in the form of cachexia.

Evaluation

Laboratory blood tests are unlikely to be diagnostic but are essential when considering the patient’s treatment plan and their ability to tolerate certain therapies. Full blood count to exclude either anemia from occult blood loss, chronic disease, or macrocytic anemia as seen in patients with high alcohol intake, common in this sub-group. Renal studies, including creatinine clearance to assess tolerance to chemotherapy. Liver enzymes for underlying alcoholic cirrhosis and liver metastasis. Serum albumin to assess the patient’s nutritional status.

Imaging forms the mainstay of diagnostic testing in hypopharyngeal cancer:[18]

- Chest X-ray looking for underlying pulmonary or cardiac disease as is common in the heavy smoking population. Also, to look for lung metastases or a synchronous lung tumor.

- Barium or Water-Soluble Contrast Swallow test can help detect any post-cricoid tumors that are not visible with the fiber-optic examination. It also picks up filling defects in the pyriform sinuses in the presence of a mucosal lesion.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan is a quick and effective way to assess tumor location, extent, spread, and nodal involvement. CT scan enhanced with the contrast of the neck, chest, and abdomen is essential in adequately staging hypopharyngeal cancer, looking for loco-regional spread as well as for distant metastases.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), especially when enhanced with gadolinium contrast, effectively detects and delineates soft tissue extension and sub-mucosal spread. A focused MRI of the oral cavity and neck gives a very detailed appraisal of the local spread of the disease.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan is useful for detecting distant metastatic spread not identified on CT scans. Often combined with CT, this modality aids with locating occult disease elsewhere in the body or perhaps localizing a primary when only a nodal metastasis is the presentation without an obvious source.

Panendoscopy, sometimes referred to as triple endoscopy, allows direct visualization of the upper aerodigestive tract under general anesthesia and the acquisition of tissue biopsy from the primary lesion as well as to establish the presence of synchronous tumors, which can be found in 10% to 15% of patients.[2]

Treatment / Management

Treatment based on a multidisciplinary team approach consisting of head and neck surgeon, medical oncology and radiation oncology, dietician, speech therapist, and patient advocate is recommended.[21] The aim is to achieve the highest degree of loco-regional control with as little impact on function as possible to preserve phonation, swallowing, and respiratory function. Guided by stage, the overall treatment scheme works accordingly:

- Early-stage (T1/T2) – Either radiotherapy alone (up to 70 Gy) or conservative surgery, perhaps with postoperative radiotherapy

- Late-stage (T3/T4) – Resectable tumors treated with partial or complete laryngopharyngectomy with selective neck dissection and postoperative chemoradiation. Unresectable tumors are treated with either radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy in combination with chemotherapy. Participation in clinical trials should be encouraged when feasible.[22][23]

The location within the sinus determines the surgical treatment options for cancers of the pyriform sinus. Early tumors of the lateral wall can be managed with partial pharyngectomy with partial resection of the lateral thyroid cartilage, particularly the upper ala. Lesions of the medial wall of the sinus are also potentially suitable for larynx sparing surgery in the form of partial laryngopharyngectomy, providing that the criteria are met. Tumors extending into the pyriform apex or posterior wall, however, are by definition more advanced at T3/T4 and, therefore, larynx sparing surgery is not an option, and a total laryngopharyngectomy is required. The same is the case for tumors extending into the post-cricoid area.[24][25][26]

Tumors in the post-cricoid region tend to be more difficult to detect clinically and present later than the other hypopharyngeal cancers and are often more advanced at the time of treatment, thus necessitating more extensive resection, reconstruction, and adjuvant therapies. Because of extension into the posterior laryngeal tissues and surgical inaccessibility, patients will more often need to undergo laryngopharyngectomy, perhaps with the addition of partial esophagectomy too, depending on the presence of esophageal invasion. Given the substantial morbidity of these larger operations, the patient’s fitness for surgery must be carefully considered. This is especially pertinent where a reconstructive flap may be required to accommodate the anatomical circumferential deficit left by the resection. Flaps most frequently take the form of a tubed radial forearm free flap to replace the resected esophagus. The cephalic vein and radial artery are anastomosed to the internal jugular vein and carotid artery, respectively, locally to supply the flap. In most instances, a neck dissection, clearing nodes from level II to VI, is required.[21]

Posterior pharyngeal wall tumor management is dictated by local invasion with mucosal lesions being amenable to wide local excision and primary closure; however, deeper spread and invasion of the prevertebral tissues is poor; a pharyngotomy will be insufficient to gain adequate histological clearance.

As may be expected, the quantity of resected tissue is associated closely with morbidity and in-hospital mortality. The type of reconstruction also affects outcomes significantly. Those patients undergoing laryngopharyngectomy requiring either a radial forearm or anterolateral thigh free flap have considerably lower mortality than a jejunal graft recipient, approximately 6%, but those needing a gastric pull up to overcome oesophageal deficit have in-hospital mortality of around 11%.[27]

Concurrent chemoradiation therapy is considered for both advanced resectable tumors and those that are unresectable, in a palliative nature. It has been established that the concurrent dosing of chemotherapy sensitizes the head and neck cancers to radiation therapy, thus increasing treatment efficacy. This translates into a significant survival benefit in comparison with delivering radiation therapy alone. The most common agent given concurrently with radiation therapy with the greatest degree of success is cisplatin, which is routinely given in combination with 5-fluorouracil.[28][29]

Differential Diagnosis

Given the high proportion of patients presenting with a new neck lump, the differentials are broad. This includes lymphadenopathy by any other cause such as acute infection, inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis, or a benign lesion like a lipoma. This could also include an acute infection or exacerbation of a hitherto undetected congenital lump such as a branchial cyst.

Other neoplasms such as that could cause both cervical lymphadenopathy and dysphagia or globus symptoms, including lymphoma, high esophageal cancer, or other head and neck cancer such as squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue base, tonsil, or elsewhere in the oropharynx.

Staging

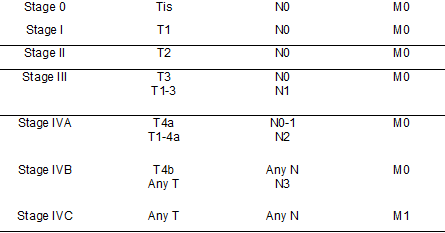

Tumor Nodal Metastases, TNM staging developed by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is the commonly used staging system, and the latest version is the 8th edition released in 2018.[30] According to the AJCC UICC TNM 8th edition, hypopharyngeal cancers are assigned a clinical stage as follows. Cancer staging derived from the TNM staging as per AJCC UICC is summarized in the table. See Table. TNM Staging.

T, the primary tumor:

TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed.

Tis Carcinoma in situ

T1 Tumour limited to one subsite of the hypopharynx and/or 2 cm or less in greatest dimension.

T2 Tumour invades more than one subsite of the hypopharynx or an adjacent site or measures more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension without fixation of hemilarynx

T3 Tumour more than 4 cm in greatest dimension, or with fixation of hemilarynx or extension to oesophageal mucosa

T4a Moderately advanced local disease; Tumour invades any of the following: thyroid/ cricoid cartilage, hyoid bone, thyroid gland, esophagus, or central compartment soft tissue.

T4b Very advanced local disease; Tumour invades prevertebral fascia, encases carotid artery, or invades mediastinal structures.

N, nodal status:

NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed.

N0 No regional lymph node metastasis

N1 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node ≤ 3 cm in greatest dimension and extranodal extension (ENE) negative

N2a Single ipsilateral lymph node ≤ 3 cm and ENE+ or single ipsilateral lymph node > 3 cm but ≤ 6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

N2b Metastases in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none > 6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

N2c Metastases in bilateral or contralateral lymph node(s), none > 6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

N3a Metastasis in a lymph node that is > 6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative

N3b Metastasis in either:

- Single ipsilateral lymph node, > 3 cm with ENE or

- Multiple ipsilateral, contralateral, or bilateral lymph nodes, any with ENE or

- Single contralateral lymph node of any size and ENE

M, metastatic status:

M0 No distant metastasis

M1 Distant metastasis

Prognosis

Hypopharyngeal cancers have a poorer prognosis compared to the other head and neck cancers owing to their late presentation and early nodal metastasis. Patients who present with an early stage lesion and no nodal metastases have a 5-year survival of up to 70%; however, given their infrequency (see below), the overall survival rate for all hypopharyngeal cancers can be as low as 20%.

The proportion of nodal disease at the presentation by tumor stage:

- T1 - 60%

- T2 - 65 to 70%

- T3 - 84%

- T4 - 85%

Tumors of the post-cricoid region and pyriform apex have a worse survival rate than those in the lateral or lateral wall of the pyriform sinus or those on the aryepiglottic fold. Unsurprisingly, tumor volume or radiological cross-sectional area is proportional to poor outcomes.[31]

Receiving post-operative radiotherapy has been proven to improve overall survival compared to those who have surgery alone.

A study from the United States determined 5-year survival based on overall stage 63 % for stage I cancers, 57.5% for stage II, 42% for stage III, and 22% for stage IV.[2]

Complications

The complications from the treatment of hypopharyngeal cancer are extensive, and morbidity can be substantial.

Surgical Complications

Intra-operative and immediately post-operative complications from surgery include hemorrhage, damage to the accessory nerve causing shoulder drop, hypoglossal nerve causing tongue dysmotility, vagus nerve (depending on how much conservation of the larynx was intended determines the significance of this lesion), and also diaphragmatic paralysis from phrenic nerve injury. Hypocalcemia and hypothyroidism if clearance of the thyroid and parathyroids is required. Graft thrombosis and necrosis in the first week post-operatively can necessitate revision. Pharyngo-cutaneous fistulae may occur, especially in the context of larger resections or postoperative radiotherapy. Depending on the surgery, long term swallowing can be adversely affected, with aspiration pneumonia being a risk if the larynx is spared and leak into the laryngectomy stoma if it is not. Longer-term complications include pharyngeal stenosis requiring dilatation procedures or long-term fistula formation.[2]

Radiotherapy Complications

With advances in recent years in the technique of administering radiotherapy to be more targeted and the use of intensity-modulated radiotherapy, the complications are less severe than previously. However, patients should still be counseled of the immediate risks of mucositis, which can be extremely painful and to the loss of salivary function, causing xerostomia, dysgeusia, mucositis, and dermatitis.[32] Patients often require a gastrostomy tube inserted pre-operatively to avoid malnutrition and to protect from the risk of aspiration. Late radiotherapy complications include structuring, long-term swallowing difficulties, and sequelae of damage to surrounding structures such as osteoradionecrosis of the mandible or vertebral bodies, spinal cord lesions, and brachial plexus injuries.

Chemotherapy Complications

The complications of chemotherapy are usually limited to the duration that treatment is received but are not underestimated as they can be severe and life-threatening. Myelosuppression and concurrent immunosuppression increase the risk of neutropenic sepsis. Other complications include alopecia, peripheral neuropathy, severe lethargy and fatigue, nausea, and vomiting. Extravasation injury from chemotherapy can be excruciating and limb-threatening. Chemotherapy also prolongs and, at times, potentiates the acute complications of radiotherapy such as mucositis.[33]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Hypopharyngeal cancer is strongly associated with lifestyle factors such as the heavy consumption of alcohol and tobacco, in both chewed and smoked forms. Public health campaigns to increase the awareness of the dangers of alcohol and tobacco consumption contribute to the reason that hypopharyngeal cancers are now seen more in developing countries around the world and to a lesser extent in those more economically developed.[34] Campaigns to reduce the consumption of areca nuts in South and Southeast Asia as well as East Africa have been shown to reduce head and neck cancers including those of the hypopharynx.[35]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of hypopharyngeal cancer through an interdisciplinary team of healthcare professionals includes otolaryngologist, radiation and medical oncologist, pathologist, radiologist, clinical nurse specialists, speech and language therapist physiotherapist is preferred.[21] Patients primarily present to their primary care physician with symptoms of painful swallowing or a vague sensation in the throat. It is essential that in the context of risk factors or not, these symptoms are considered strongly as indicators of cancers in the hypopharynx, and the urgent opinion of an otolaryngology specialist is sought.

Head and neck cancers are complex in their planning and delivery of treatment, and patients need thorough and detailed follow-up based both in hospital and in the community setting. Patients require coordinated education and support in the run-up to treatment in preparation for both the side effects of treatment and the path to regaining phonation and deglutition. [Level 5]