Continuing Education Activity

Hearing aids, perhaps obviously, amplify sound so that a patient with a hearing deficit can hear better. This activity describes the indication and selection of commonly used hearing aids. It highlights the clinical significance of hearing loss and the role of the professionals involved in ear and hearing services.

Objectives:

Identify the components of a conventional hearing aid.

Review the indications for a conventional hearing aid.

Summarize the common varieties of conventional hearing aids.

Outline some interprofessional strategies that the healthcare team can use when assisting a patient in the hearing aid selection process.

Introduction

This article will discuss the indications and selection of conventional hearing aids. Conventional hearing aids are non-invasive (not requiring surgery) and are placed behind the pinna, in the canal, or are body-worn. Invasive hearing aids, including bone-anchored hearing aids and cochlear implants, are excluded from coverage in this chapter.

Hearing aids, by definition, are sound-amplifying devices that increase the user's ability to detect noise.[1] The components of a non-invasive hearing aid vary widely but broadly consist of a microphone, amplifier, receiver, and battery. The microphone converts external acoustic energy into electrical energy, which is amplified by the amplifier. The receiver detects this and converts it back into acoustic energy, projecting sound into the ear canal. The amplification is driven by the battery, which can be made from zinc-air batteries, mercury, alkaline or rechargeable batteries. A non-invasive hearing aid aims to increase the sound levels delivered to and hence detected by the hair cells in the cochlea.

Function

Indication

Hearing aids can be used to treat the majority of hearing impairments. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK states that hearing aids should be offered to adults whose hearing loss affects their ability to communicate and hear, including awareness of warning sounds, their environment, and listening to music. Therefore, hearing aids may be indicated in various pathologies that cause sensorineural hearing loss, conductive hearing loss, or single-sided hearing loss.[2] The degree of subjective and objective loss and patient choice are taken into account when deciding on a hearing aid. The benefit of a conventional hearing aid decreases as the degree of loss becomes severe-profound. This is due to a limited amplification capacity. In these cases, invasive hearing aids may be indicated.[2]

Selection

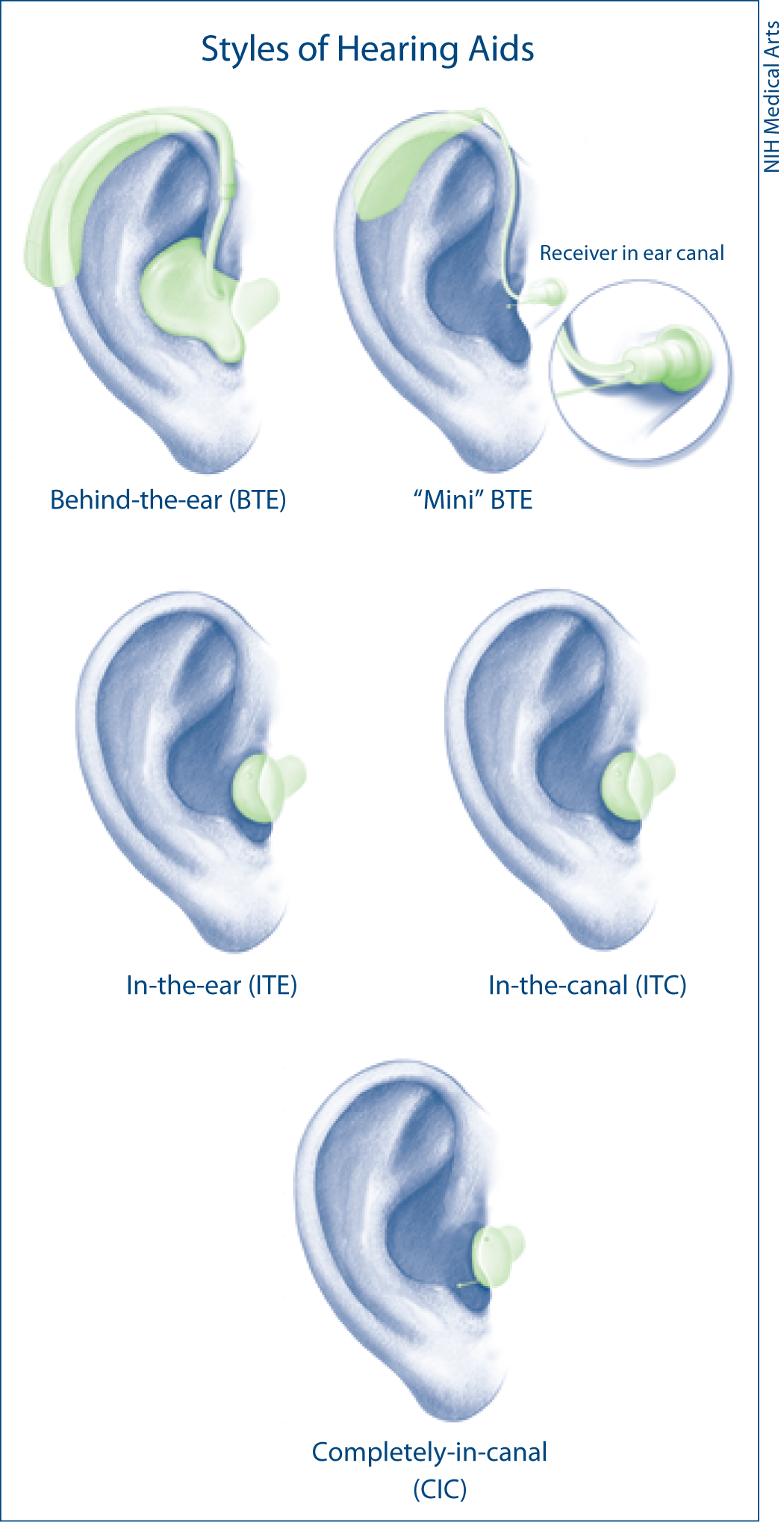

There are various hearing aids, and their selection is not a ‘one-size fits all’ approach (see Illustration. Styles of Hearing Aids). Selection is influenced by factors that include audiometric deficit (laterality, frequency, and degree of loss), cosmesis, and the patient’s needs, lifestyle, and priorities.[3] Here we describe the advantages and limitations of commonly used hearing aids.

Behind the ear (BTE) hearing aids sit behind the pinna. A plastic tube connects the hearing aid to an earmold or ‘open’ silicone ear tip according to the patient's needs. They are commonly used because they are capable of various levels of amplification, and their power and performance can be modified relatively easily.[4] They are robust, cheap, and easier to manipulate for patients with reduced dexterity. Patients who require amplification for moderate to profound hearing loss will require an earmould, which may be less cosmetically appealing than the open-fitting option.

The receiver in the canal (RIC) hearing aids are similar to the BTE, except the receiver is located at an ‘open’ silicone earpiece that sits in the canal, rather than inside the hearing aid casing near the microphone and amplifier. This set up allows higher amplification levels without the risk of acoustic feedback (sound escaping the canal and circling back through the hearing aid again), thus more suited to patients with high frequency ‘ski-slope’ hearing losses and those who prioritize cosmetics of the device. They also provide a clearer and more natural sound, amplifying higher frequencies better, with less occlusion of low frequencies (as the ear canal is kept ‘open’).[4] This is important as high-frequency loss (seen often in presbycusis) is the most common type of hearing loss.[2] However, its ‘open’ design is susceptible to sound distortion by ambient sound, especially in noisy environments. Patients with reduced manual dexterity (elderly, pediatric, or arthritic patients) may find them harder to use, and they are also more prone to noise feedback. The RIC hearing aid is also more prone to bio-degradation as it is exposed to cerumen. Finally, they are less suitable for patients with frequent ear infections.

In the ear (ITE), in the canal (ITC), and completely in the canal (CIC), hearing aids are broadly grouped as custom-shape hearing aids. These are the most discrete hearing aids and, therefore, advantageous in a patient population that prefers an improved aesthetic. They can be used in a range of hearing losses, and because the receiver is closer to the eardrum, there is better amplification of high frequencies, important for speech discrimination.[4] This is useful in environments that have a high level of background noise and in patients with presbycusis. However, like RIC and open canal hearing aids, custom-made hearing aids may not be suitable if large amounts of amplification are needed, as they use smaller batteries.

Finally, contralateral routing of signals (CROS) and bilateral contralateral routing of signals (BiCROS) are used for unilateral hearing loss and asymmetrical hearing loss, respectively, in cases where a conventional hearing aid provides little benefit. Here, a microphone is placed on the side of worse hearing, and the signal is transmitted to the better hearing ear, where this signal is amplified. For BiCROS, used in asymmetrical hearing loss (e.g.mild-moderate on one side and severe-profound on the other), there are two microphones, one on each ear, with sound from both microphones amplified into the better hearing ear.

Issues of Concern

A range of factors needs to be considered before referring a patient for hearing aid fitting.

Audiology

Pure tone audiometry (PTA) indicates the type, extent, and laterality of loss. PTA data informs the number of hearing aids (unilateral or bilateral) and the type of hearing aid needed (some hearing aids cannot amplify sufficiently for severe-profound hearing loss or perform better across certain frequencies). Bilateral hearing aids may improve speech recognition and localization but can increase interference, are cosmetically less pleasing, and are more expensive.[5]

Conductive deficits resultant of acute infection or wax should not be treated with a hearing aid. Audiologists' further tests to inform hearing aid programming include speech audiometry results and uncomfortable loudness levels (ULLs) to establish the patient’s dynamic range; the range in sound pressure level (dB SPL) between the patient’s hearing thresholds and the point at which sounds become uncomfortably loud. Hearing aids generally work better in patients with a large dynamic range.

Anatomy

A further factor to consider is the patient's ear anatomy, which can vary significantly. The pinna has to be able to support the processor and battery, and the custom made earmould. The ear canal needs to be wide enough to accommodate hearing aid components. Cases of pinna atresia or canal stenosis/atresia may require invasive hearing aids, not covered in this chapter.

Patient Factors

Importantly, the lifestyle, concerns, and expectations of the hearing aid user should be explored. The communication needs of each user will vary, including the setting (occupational or social) and frequency of communication. There may also be concerns regarding cost, cosmesis, sound quality, and the level of dexterity required to operate the hearing aid.[3] All of these factors may influence the final hearing aid of choice.

Clinical Significance

Worldwide, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that over 5% of people have disabling hearing loss, defined as a hearing deficit of 40 dB in the better hearing ear in adults and a hearing loss exceeding 30 dB in the better hearing ear in children. Only a fifth of people who would benefit from a hearing aid actually use one. Hearing loss is associated with social isolation and depression, which is suggested to be twice as prevalent in hearing loss.[6] It has also been identified as an independent risk factor for cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease.[7]

Current estimates are that the prevalence of Alzheimer disease is doubling every 20 years due to an aging population. Furthermore, hearing loss is associated with lower employment rates and further societal and economic sequelae. Therefore, identifying and correctly treating patients with hearing loss is paramount. Conventional hearing aids are a cornerstone of management, and therefore familiarity with their selection and indication is important for healthcare professionals working in ear and hearing services.

Other Issues

Other issues to be aware of include:

- Battery life- a battery can last from 3 to 22 days, dependent on the type of hearing aid, frequency of use, required amplification, and any modern modifications (see below) that are used.

- Hearing aid cleaning and risk of earwax clogging - the patient should be counseled and educated on how to look after their hearing aid.

- Modern modifications- selected modern hearing aids are capable of Bluetooth, variable programming, wireless, and can house rechargeable batteries. These features impact the cost of the hearing aid and aren't ubiquitously available.

- Assistive listening devices (ALDs)

- Social and familial support around the user

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A patient requiring a conventional hearing aid may encounter a range of professionals working within ear and hearing services. Medically trained audio-vestibular physicians and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeons will investigate the cause of hearing loss and may refer to audiology for testing and fitting. There will be regular contact with an audiologist, a clinically trained healthcare professional in diagnosing and managing adult and child hearing loss and balance, who performs the audiometric tests, hearing aid fitting, and maintenance. In lower and middle-income countries, where resources can vary, ENT surgeons may also perform this role.[8]

ENT surgeons can manage patients with any complications of conventional hearing aids such as earwax impaction, external ear infection, and foreign body in the ear when a part of the hearing aid may break off into the ear canal.