Introduction

Each hand consists of 27 bones. The osseous anatomy of the human hand is integral to its impressive functionality. The purpose of this article is to provide a review of hand osteology for the education of current and future healthcare providers.

Structure and Function

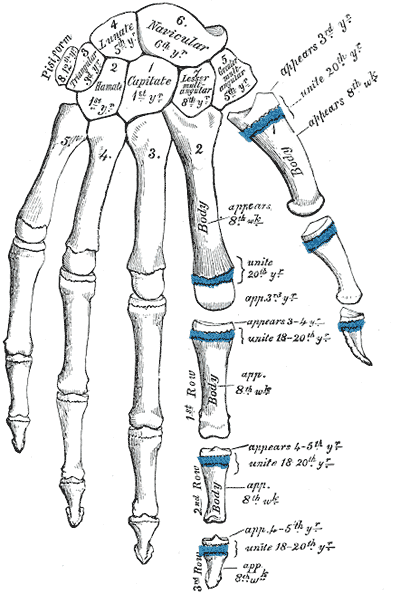

The carpus (proximal and distal rows), metacarpal bones, phalanges, and various sesamoid bones form the skeletal hand.[1][2] The hand has five metacarpals, fourteen phalanges, and four consistently present sesamoid bones.

The wrist connects to the hand at the carpometacarpal (CMC) joints.[3] The first CMC forms from the articulation between the trapezium and the base of the first metacarpal. The base of the second metacarpal articulates with trapezium, trapezoid, and capitate. The base of the third metacarpal articulates with capitate. The base of the fourth metacarpal articulates with capitate and hamate. The fifth metacarpal's base articulates with the hamate.[4][5]

The first metacarpal bone corresponds to the thumb, the second to the index finger, the third to the long finger, the fourth to the ring finger, and the fifth to the small finger. The thumb has two phalanges, named proximal and distal phalanges. The proximal phalanx base forms the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint with the first metacarpal head.[6] The head of the proximal phalanx articulates with the base of the distal phalanx to form the interphalangeal (IP) joint.

The index, long, ring, and small fingers each have proximal, middle, and distal phalanges. The proximal phalanges form MCP joints with their respective metacarpal bones. The head of each proximal phalanx articulates with the base of each middle phalanx to form proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints. The head of each middle phalanx articulates with the base of each distal phalanx to form distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.[7]

Two sesamoid bones are present at the first MCP joint. These are consistently present and have significant functional implications for the motion of the thumb. Single sesamoids appear over the second and fifth MCP joints in 60.8% and 59.1% of the population, respectively.[8]

Embryology

The limb bud first appears in the proximal fetus around the fifth week of development. From this point, various HOX genes govern the growth of the limb. The stylopod, zeugopod, and autopod are the three growth zones of the limb bud corresponding to the humerus, ulna and radius, and hand, respectively. Ectoderm differentiates into the apical ectodermal ridge, non-ridge ectoderm, and zone of polarizing activity. These zones carry essential roles in differentiation. For example, the removal of the apical ectodermal ridge early in limb development will result in the presence of only stylopod development. Removal of the apical ectodermal ridge later in development will result in the formation of the stylopod and zeugopod but no autopod, leading to the fetus not developing a hand.[9]

The HOXA and HOXD genes are responsible for the embryologic development of the hand in humans. HOXA is responsible for anteroposterior growth, while HOXD is responsible for proximodistal growth.[10]

Research has demonstrated that the metacarpal bone length can contribute to the estimation of fetal development during the prenatal period, which may help evaluate any anomalies. Utilizing this in combination with foot lengths and other accepted estimates of development can provide a more comprehensive picture.[11]

Due to the complexity of the structure of the hand, a myriad of morphologic anomalies may occur during development.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to the hand comes from the ulnar and radial arteries, which are branches of the brachial artery. Dorsal hand vascular supply comes from the dorsal carpal arch. This arch forms from anastomosis of the dorsal carpal branches of radial and ulnar arteries. Metacarpal branches subsequently arise from the dorsal carpal arch. The first metacarpal branch courses along the radial border of the second metacarpal, supplying the first web space and second metacarpal. The second through fifth branches course along the ulnar borders of the second through fifth metacarpals and provide branches to the interosseous muscles as well as the periosteum.[12]

The superficial palmar arterial arch is primarily formed by the ulnar artery, while the radial artery mainly supplies the deep palmar arterial arch. Metacarpal branches generally arise from the deep arch, while digital arteries arise from the superficial arch. Metacarpal branches form anastomosis with digital arteries.[13]

Physiologic variation of arterial flow in the hand is plentiful, with a multitude of anastomoses and variations in flow dominance.[14]

Nerves

Innervation to the hand is from the median, ulnar, and radial nerves.[15][16][17] Each digit/ray has two palmar and two dorsal digital nerves. The median nerve innervates the cutaneous volar aspect of the first three and a half digits. The ulnar nerve entirely innervates the dorsal and volar ulnar half of the fourth and fifth digits. The radial nerve innervates the remainder of the dorsal hand. Due to the complex functionality of the hand, it is vital that clinicians reliably report and understand proprioception and grasp strength. Multiple innervation distribution is provided to the MCPs, PIPs, and DIPs to facilitate this understanding.[18]

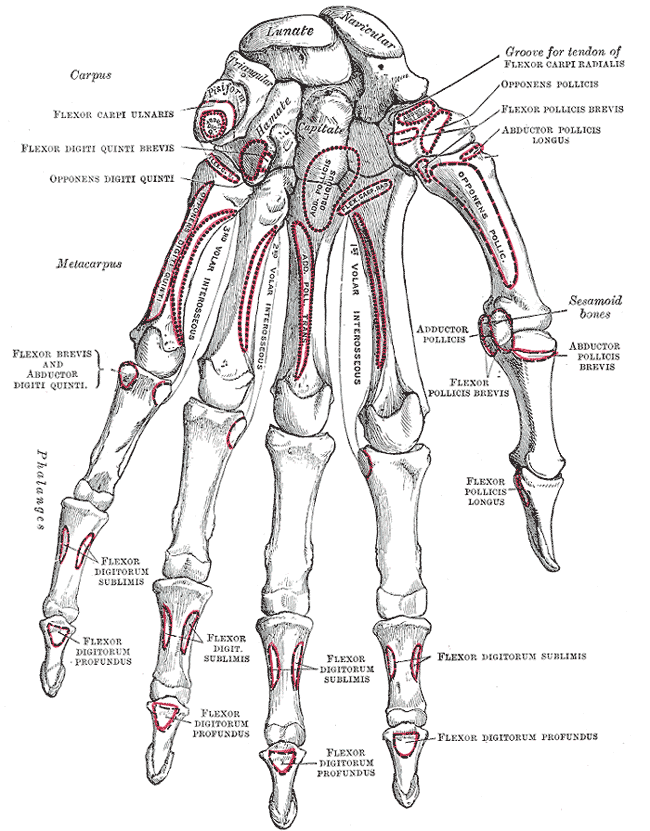

Muscles

Three volar interossei muscles adduct the second, fourth, and fifth digits about an axis formed by the third digit. These muscles originate on the metacarpal of the digit being adducted and insert onto their respective proximal phalangeal base and extensor hood. Adduction occurring along this third digit axis means that the volar interosseous muscle of the second digit is located on its ulnar border, while the interossei of the fourth and fifth digits reside on their radial borders.[19]

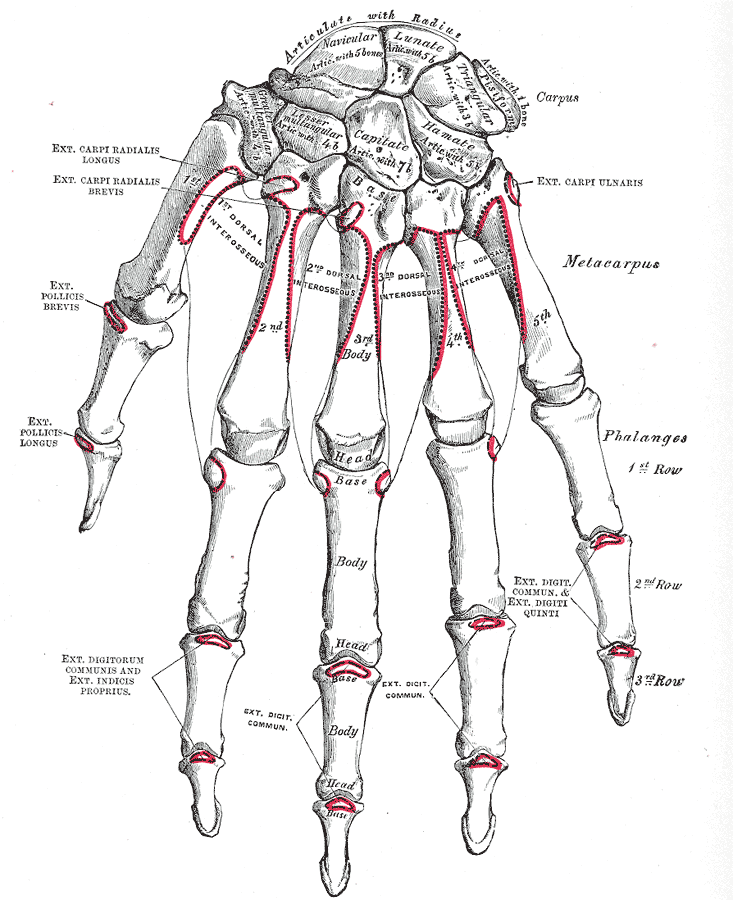

Four dorsal interossei work to abduct the second, third, and fourth digits while assisting with flexion of the MCPs, extension of the PIPs, and extension of the DIPs. The first dorsal interosseous muscle originates from the first and second metacarpals, inserting onto the radial base of the proximal phalanx of the second digit as well as its extensor hood. The second dorsal interosseous muscle originates from the second and third metacarpals, inserting onto the radial base of the proximal phalanx of the third digit as well as its extensor hood. The third dorsal interosseous muscle originates from the third and fourth metacarpals, inserting onto the ulnar base of the proximal phalanx of the third digit as well as its extensor hood. The fourth dorsal interosseous muscle originates from the fourth and fifth metacarpals, inserting onto the ulnar base of the proximal phalanx of the fourth digit as well as its extensor hood.[19]

Abductor pollicis longus (APL) originates in the forearm, at the midshaft of the radial border of the ulna, the ulnar border of the radius, and the interosseous membrane. The muscle inserts to the radial side of the base of the first metacarpal in addition to the trapezium and opponens pollicis fascia.[20] This muscle acts to abduct the first digit.

Abductor pollicis brevis (APB) originates at the trapezium and scaphoid and inserts onto the lateral base of the proximal phalanx of the first digit. This muscle acts in first-digit abduction in addition to MCP flexion.[21]

Extensor pollicis longus (EPL) originates at the radial border of the ulna and interosseous membrane, distal to the origin of APL. EPL inserts to the base of the distal phalanx and acts to extend the interphalangeal joint.[20]

Extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) originates at the ulnar border of the radius and interosseous membrane at the level of EPL. This muscle inserts to the base of the proximal phalanx of the first digit and aids in the first digit extension at the MCP.[20]

Opponens pollicis acts to pronate the first metacarpal; it originates at the trapezium and inserts onto the anterolateral aspect of the first metacarpal.[21]

Flexor carpi radialis (FCR) originates at the medial humeral epicondyle and inserts onto the trapezium, second metacarpal, and third metacarpal. FCR acts to flex and radially deviate the wrist.[22]

Flexor pollicis brevis (FPB) has a deep and superficial head. The deep head originates at the second metacarpal, while the superficial head originates at the transverse carpal ligament and trapezium. These insert onto the lateral base of the proximal phalanx of the first digit and act to flex the MCP.[21]

Flexor pollicis longus (FPL) is the primary flexor of the first digit, originating from the volar interosseous membrane and radius. The muscle inserts onto the base of the distal phalanx.[23]

The Adductor pollicis has two heads, an oblique and transverse. The oblique head originates at the capitate, second, and third metacarpals. The transverse head originates at the distal half of the third metacarpal shaft. These both insert onto the medial base of the thumb proximal phalanx and act to adduct the first digit.[21]

Abductor digiti minimi (ADM) acts to abduct the fifth digit and has been found to originate at the pisiform, piso-hamate ligament, and flexor carpi ulnaris. The muscle inserts onto the ulnar aspect of the proximal phalangeal base and extensor apparatus of the fifth digit.[24]

Flexor digiti minimi (FDM) originates from the hamate, pisiform, and flexor retinaculum. Distally, the flexor digiti minimi fuse with the ADM to insert onto the proximal phalangeal base of the fifth digit, leading to its action of MCP flexion.[24]

Extensor carpi ulnaris originates at the lateral humeral epicondyle and inserts onto the dorsal base of the fifth metacarpal, acting in wrist extension and ulnar deviation.[25]

Flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) has a broad origination from the medial epicondyle of the humerus and coronoid process of the ulna to the volar aspect of the radial shaft. The muscle then inserts onto the middle phalangeal bases of the second through fifth digits. This acts primarily in PIP flexion.[26]

Flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) originates from the volar-medial aspect of the ulna and interosseous membrane and inserts at the distal phalangeal bases of the second through fifth digits. This performs DIP flexion.[27]

Extensor digitorum communis (central slip and terminal tendons) originates at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and inserts at the dorsal aspect of the distal phalangeal base of the second through fifth digits. There is significant anatomic variation in the accessory slips and insertions of this muscle, but the classic teaching is that there is an insertion to the middle phalanx and MCP in addition to this consistently present terminal insertion.[28]

Physiologic Variants

There is a great deal of physiologic variation between individuals in the morphology of the hand bones. One tool used to discuss the variance in hand anatomy is the digit length ratio of the second to the fourth digit, otherwise referred to as the 2D to 4D ratio. This number has been demonstrated to be 0.98 among the general population but shows variability between ethnicities, races, and sexes, as well as the patient's handedness. The third digit is consistently the longest of the digits. The most significant source of variance in the hand bones is the result of differences in size.[10]

Surgical Considerations

Metacarpal fractures should undergo fixation if there is any component of malrotation to ensure that patients can make a closed fist and grip properly.

Surgery is indicated in treating these fractures when the fracture pattern falls outside of acceptable angulation tolerances, and thus the patient’s functional outcome would benefit from surgical fixation by lag screw fixation and/or plating techniques or via percutaneous pinning of the fractures.[29][2]

Tolerances for fractures of the shaft and neck of each metacarpal vary, with the index tolerating the least angulation and the little finger tolerating the most. Fractures of the fifth metacarpal neck, otherwise known as boxer’s fractures, highlight the good outcomes of nonoperative treatment of most of these fractures.[30][31]

include MCP or IP dislocations that are irreducible and will also need to undergo surgical fixation to facilitate the restoration of function.[32] Phalanx fractures with displacement, nonunion, malunion, ipsilateral extremity fractures, pathologic fractures, or multiple unstable ipsilateral hand fractures may require surgical intervention.[33]

Dorsal intraarticular fractures of the distal phalanx, otherwise known as mallet finger, rarely need to undergo surgical fixation, but intervention is indicated with greater than 30 percent involvement of the articular surface or for volar subluxation of the distal phalanx.[34] Volar interarticular avulsion fractures of the distal phalanx, also known as jersey finger, by in large, require surgical fixation for the restoration of flexor digitorum profundus function.[35]

Clinical Significance

Small Joint Osteoarthritis: This condition characteristically demonstrates Heberden and Bouchard nodes of the DIP and PIP, respectively (mnemonic: B comes before H). These nodes represent the cutaneous manifestations of joint space narrowing and osteophyte formation resulting from osteoarthritis. Research shows a positive correlation between the appearance of these nodes and the underlying osteoarthritis.[36]

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): is a form of arthritis that often presents with prominent hand manifestations. Swan neck and boutonniere deformities are classically described, in addition to the ulnar deviation of the digits. The swan neck deformity is characterized by DIP flexion with PIP extension, while the inverse is true of the boutonniere deformity. Nowadays, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have reduced the severity of hand disease seen in RA, but early intervention should be started to prevent disability and progressive joint erosion seen in the natural course of the disease.[37]

Ape Hand: is characterized by thenar eminence wasting. This is the consequence of loss of the median nerve, as in carpal tunnel syndrome or a relatively superficial cut on the medial aspect of the halfway point of the thenar eminence. The lesion of the recurrent branch of the median nerve denervates the abductor pollicis brevis, superficial head of the flexor pollicis brevis, and opponens pollicis.

If all the median nerve in the hand is denervated, the first and second lumbricals will also be affected. The long extensors act upon the hand, so the hand appears to lack an opposable thumb (as in apes). The patient is unable to oppose the thumb. Flexion of the thumb may be weaker, but the flexor pollicis longus is intact and much more powerful than the flexor pollicis brevis. In addition, the deep head of the flexor pollicis brevis is innervated by the deep branch of the ulnar nerve. Because the abductor pollicis longus intact (posterior interosseous nerve from the radial nerve), abduction still occurs.

Bishop Hand (Hand of Benediction or Preacher Hand): occurs in a median nerve palsy. When the patient attempts to make a first, the ring and little fingers flex, but the index and fingers remain extended. This finding is due to the denervation of all the flexor digitorum superficialis and the flexor digitorum profundus muscle slips for the index and ring finger. The loss of the first and second lumbricals also contributes to the straightening (extension) of the index and middle fingers. Flexion of the ring and little finger is weaker due to the loss of the flexor digitorum superficialis to these fingers, but the muscle slips to these fingers from the flexor digitorum profundus are still intact, as are the third and fourth lumbricals. It should be noted that the patient must make a fist for the extension of the index and middle finger to remain extended.[38]

Boutonniere Deformity: The MCP (metacarpophalangeal) joints and the DIP (distal interphalangeal) joints are affected. The primary damage is to flexion of the proximal interphalangeal joints due to damage to the central portion of the extensor hood. The boutonnière deformity is usually caused by rheumatoid arthritis. The term boutonnière refers to a buttonhole such as one might place a flower during a ceremony such as marriage.

Nail Disorders: Beau lines are transverse ridges or lines caused by interruption of nail growth due to nutritional deficiency states. There are a number of conditions that can cause Beau lines. Clubbed nails are due to respiratory diseases such as obstructive pulmonary disease and severe emphysema, as well as cardiac diseases such as congenital cardiac defects and cor pulmonale. Mees lines take the form of white transverse lines. They can be caused by arsenic and thallium poisoning and high fevers. Spoon-shaped nails have a scooped depression that may be due to a number of causes, including anemia (including iron deficiency anemia), fungal infection, prolonged diabetes mellitus, psoriasis, and genetic abnormalities.[39][40]

Palmar Arch Arterial Bleeding: can produce uncontrollable bleeding due to lesions of the palmar arterial arches. The best way to control the bleeding is to compress the brachial artery onto the humerus.

Polydactyly: This defect occurs once every 700 to 1000 live births, making it a relatively common anatomical variant. There are various types of polydactyly, and they can broadly categorize as syndromic or non-syndromic. Subtypes of polydactyly exist based on the point of origination of the extra digit. Though the identities of the exact genetic links are still a work in progress, patients who present with polydactyly should have a careful workup to rule out underlying conditions.[41]

Trigger Finger: results from the thickening of the finger tendon sheath. This thickening causes sticking of the finger when it is flexed. The thickening is due to inflammation of the sheath. As the finger sticks when it is flexed, it eventually releases with a snap. This condition is more likely in females than males. This deformity is most often associated with rheumatoid arthritis.[42][43][44]

Ulnar Drift of the Hand: most commonly occurs in rheumatoid arthritis. The deviation of the hand toward the ulnar side occurs at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints due to the bowing of the ligaments of the extensor digitorum.

Ulnar Claw Hand (Claw Hand): this is due to a lesion of the ulnar nerve. The MCP joints are hyperextended for the ring and little fingers due to the loss of the third and fourth lumbrical muscles due to a lesion of the deep branch of the ulnar nerve. The dorsal and ventral interossei are lost, but the ring and middle fingers are not clawed due to the presence of the intact first and second lumbricals, which are innervated by the median nerve.

The ability to oppose the little finger and the ability to adduct the thumb will be lost due to the lesion of the deep branch of the ulnar nerve. If the lesion occurs higher in the forearm (medial epicondylar fracture), there will be radial deviation due to loss of the flexor carpi ulnaris. The strength of the flexion of the ring and little fingers is decreased due to the loss of the flexor digitorum profundus to these digits. Loss of sensory function to the medial half of the ring finger and all the little fingers will occur.

Sensation to the medial side of the dorsum of the hand will be lost due to a lesion of the dorsal cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve. The medial forearm will not be affected because the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm is derived from the medial cord of the brachial plexus.[45][46]

Wrist Drop Deformity: occurs with a lesion to the radial nerve. The wrist and finger extensors are denervated, so the digits cannot be extended. The test for wrist drop involves having the examiner hold the forearm in a stable horizontal position. The examiner holds the patient's hand with his other hand. The patient attempts to extend the hand against resistance. The results are compared with the other hand.

Some variations in the lesion leads to wrist drop. In the first case, the lesion involves a mid-humeral or supracondylar radial fracture. The branches to the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus are given off first and are much smaller than the radial nerve itself. Thus they may be spared, although the rest of the nerve is lost. When the hand is held in the flexed ("dropped") position, the extensor carpi radialis longus will cause weak extension and radial deviation of the hand.

Wrist drop is also seen in lesions of the posterior interosseous nerve, which is formed from the deep branch of the radial nerve as it emerges from beneath the arcade of Frohse. When a patient with a posterior interosseus neuropathy is tested for "drop hand," the extensor carpi radialis brevis and extensor carpi radialis longus are intact; thus, the patient will exhibit weak extension of the radial side of the hand with radial deviation of the hand.[47]

Sensory changes of the radial neuropathy are as follows. The proximal radial nerve gives rise to the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm, which is only involved in proximal radial neuropathies. The radial nerve in the antecubital fossa divides into the superficial (sensory) radial nerve, which emerges on the radial side of the hand, and the deep (motor) branch. The superficial (sensory) branch supplies the dorsum of the hand on the radial side. Sensation can be tested for over the dorsum of the thenar web. Branches supply the digits to a variable degree. The base of the phalanges may be involved in the index and middle fingers. The tips of the fingers are only supplied by the median nerve (index, ring, and lateral half of ring finger and the ulnar nerve (medial half of ring finger and all of the little finger).

Zigzag Thumb Deformity: The thumb is flexed at the carpometacarpal joint (CMJ) and extended at the metacarpophalangeal joint (CMJ). This deformity is characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. Other cases may be due to genetic hypermobility.[48][49]