[1]

Mao XC, Yu WQ, Shang JB, Wang KJ. Clinical characteristics and treatment of thyroid cancer in children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis of 83 patients. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B. 2017 May:18(5):430-436. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600308. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28471115]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[2]

Mileva M, Stoilovska B, Jovanovska A, Ugrinska A, Petrushevska G, Kostadinova-Kunovska S, Miladinova D, Majstorov V. Thyroid cancer detection rate and associated risk factors in patients with thyroid nodules classified as Bethesda category III. Radiology and oncology. 2018 Sep 27:52(4):370-376. doi: 10.2478/raon-2018-0039. Epub 2018 Sep 27

[PubMed PMID: 30265655]

[3]

Kim K, Cho SW, Park YJ, Lee KE, Lee DW, Park SK. Association between Iodine Intake, Thyroid Function, and Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Case-Control Study. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2021 Aug:36(4):790-799. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1034. Epub 2021 Aug 11

[PubMed PMID: 34376043]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[4]

Kitahara CM, Pfeiffer RM, Sosa JA, Shiels MS. Impact of Overweight and Obesity on US Papillary Thyroid Cancer Incidence Trends (1995-2015). Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2020 Aug 1:112(8):810-817. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz202. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31638139]

[5]

Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA. 2006 May 10:295(18):2164-7

[PubMed PMID: 16684987]

[6]

Casella C, Fusco M. Thyroid cancer. Epidemiologia e prevenzione. 2004 Mar-Apr:28(2 Suppl):88-91

[PubMed PMID: 15281612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[7]

Kitahara CM, Sosa JA, Shiels MS. Influence of Nomenclature Changes on Trends in Papillary Thyroid Cancer Incidence in the United States, 2000 to 2017. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2020 Dec 1:105(12):e4823-30. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa690. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32984898]

[8]

Arroyo N, Bell KJL, Hsiao V, Fernandes-Taylor S, Alagoz O, Zhang Y, Davies L, Francis DO. Prevalence of Subclinical Papillary Thyroid Cancer by Age: Meta-analysis of Autopsy Studies. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2022 Sep 28:107(10):2945-2952. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac468. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 35947867]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[9]

Krajewska J, Kukulska A, Oczko-Wojciechowska M, Kotecka-Blicharz A, Drosik-Rutowicz K, Haras-Gil M, Jarzab B, Handkiewicz-Junak D. Early Diagnosis of Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer Results Rather in Overtreatment Than a Better Survival. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2020:11():571421. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.571421. Epub 2020 Oct 6

[PubMed PMID: 33123090]

[10]

Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA. 2017 Apr 4:317(13):1338-1348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2719. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28362912]

[11]

Rogucki M, Buczyńska A, Krętowski AJ, Popławska-Kita A. The Importance of miRNA in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021 Oct 15:10(20):. doi: 10.3390/jcm10204738. Epub 2021 Oct 15

[PubMed PMID: 34682861]

[12]

Tao Y, Wang F, Shen X, Zhu G, Liu R, Viola D, Elisei R, Puxeddu E, Fugazzola L, Colombo C, Jarzab B, Czarniecka A, Lam AK, Mian C, Vianello F, Yip L, Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Santisteban P, O'Neill CJ, Sywak MS, Clifton-Bligh R, Bendlova B, Sýkorová V, Zhao S, Wang Y, Xing M. BRAF V600E Status Sharply Differentiates Lymph Node Metastasis-associated Mortality Risk in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2021 Oct 21:106(11):3228-3238. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab286. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 34273152]

[13]

Ge J, Wang J, Wang H, Jiang X, Liao Q, Gong Q, Mo Y, Li X, Li G, Xiong W, Zhao J, Zeng Z. The BRAF V600E mutation is a predictor of the effect of radioiodine therapy in papillary thyroid cancer. Journal of Cancer. 2020:11(4):932-939. doi: 10.7150/jca.33105. Epub 2020 Jan 1

[PubMed PMID: 31949496]

[14]

Celik M, Bulbul BY, Ayturk S, Durmus Y, Gurkan H, Can N, Tastekin E, Ustun F, Sezer A, Guldiken S. The relation between BRAFV600E mutation and clinicopathological characteristics of papillary thyroid cancer. Medicinski glasnik : official publication of the Medical Association of Zenica-Doboj Canton, Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2020 Feb 1:17(1):30-34. doi: 10.17392/1086-20. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31994851]

[15]

Jensen K, Thakur S, Patel A, Mendonca-Torres MC, Costello J, Gomes-Lima CJ, Walter M, Wartofsky L, Burman KD, Bikas A, Ylli D, Vasko VV, Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J. Detection of BRAFV600E in Liquid Biopsy from Patients with Papillary Thyroid Cancer Is Associated with Tumor Aggressiveness and Response to Therapy. Journal of clinical medicine. 2020 Aug 2:9(8):. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082481. Epub 2020 Aug 2

[PubMed PMID: 32748840]

[16]

Choi JB, Lee SG, Kim MJ, Kim TH, Ban EJ, Lee CR, Lee J, Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Nam KH, Chung WY, Park CS. Oncologic outcomes in patients with 1-cm to 4-cm differentiated thyroid carcinoma according to extent of thyroidectomy. Head & neck. 2019 Jan:41(1):56-63. doi: 10.1002/hed.25356. Epub 2018 Dec 10

[PubMed PMID: 30536465]

[17]

Al-Brahim N, Asa SL. Papillary thyroid carcinoma: an overview. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2006 Jul:130(7):1057-62

[PubMed PMID: 16831036]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[18]

Cho H, Kim JY, Oh YL. Diagnostic value of HBME-1, CK19, Galectin 3, and CD56 in the subtypes of follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Pathology international. 2018 Nov:68(11):605-613. doi: 10.1111/pin.12729. Epub 2018 Oct 23

[PubMed PMID: 30350394]

[19]

Rahmat F, Kumar Marutha Muthu A, S Raja Gopal N, Jo Han S, Yahaya AS. Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma as a Lateral Neck Cyst: A Cystic Metastatic Node versus an Ectopic Thyroid Tissue. Case reports in endocrinology. 2018:2018():5198297. doi: 10.1155/2018/5198297. Epub 2018 Oct 18

[PubMed PMID: 30420925]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[20]

Zhao H, Huang T, Li H. Risk factors for skip metastasis and lateral lymph node metastasis of papillary thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2019 Jul:166(1):55-60. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.01.025. Epub 2019 Mar 12

[PubMed PMID: 30876667]

[21]

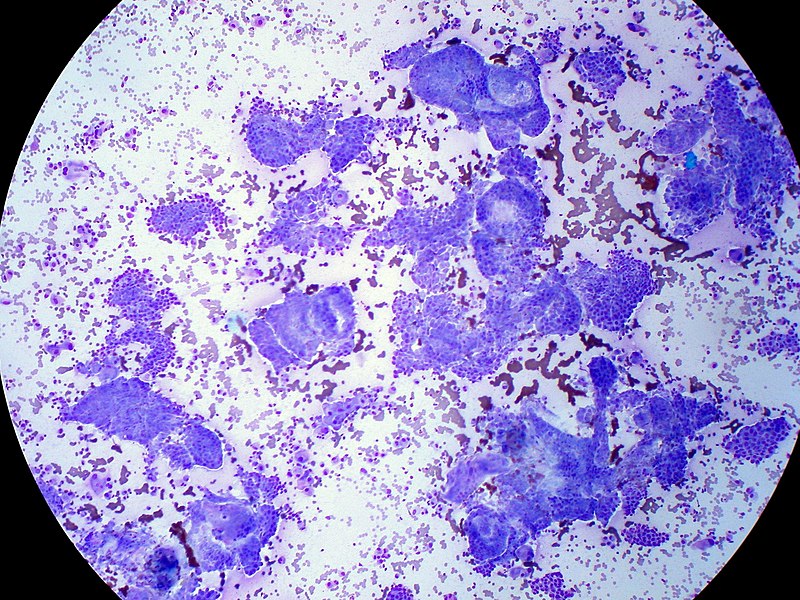

Nasser SM, Pitman MB, Pilch BZ, Faquin WC. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of papillary thyroid carcinoma: diagnostic utility of cytokeratin 19 immunostaining. Cancer. 2000 Oct 25:90(5):307-11

[PubMed PMID: 11038428]

[22]

Nishino M, Krane JF. Updates in Thyroid Cytology. Surgical pathology clinics. 2018 Sep:11(3):467-487. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2018.05.002. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30190135]

[23]

Suzuki S, Bogdanova TI, Saenko VA, Hashimoto Y, Ito M, Iwadate M, Rogounovitch TI, Tronko MD, Yamashita S. Histopathological analysis of papillary thyroid carcinoma detected during ultrasound screening examinations in Fukushima. Cancer science. 2019 Feb:110(2):817-827. doi: 10.1111/cas.13912. Epub 2019 Jan 20

[PubMed PMID: 30548366]

[24]

Gilmartin A, Ryan M. Incidence of Thyroid Cancer among Patients with Thyroid Nodules. Irish medical journal. 2018 Sep 10:111(8):802

[PubMed PMID: 30547520]

[25]

McLeod DSA, Zhang L, Durante C, Cooper DS. Contemporary Debates in Adult Papillary Thyroid Cancer Management. Endocrine reviews. 2019 Dec 1:40(6):1481-1499. doi: 10.1210/er.2019-00085. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31322698]

[26]

Haugen BR. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: What is new and what has changed? Cancer. 2017 Feb 1:123(3):372-381. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30360. Epub 2016 Oct 14

[PubMed PMID: 27741354]

[27]

Cho SJ, Suh CH, Baek JH, Chung SR, Choi YJ, Chung KW, Shong YK, Lee JH. Active Surveillance for Small Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2019 Oct:29(10):1399-1408. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0159. Epub 2019 Sep 27

[PubMed PMID: 31368412]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[28]

Coca-Pelaz A, Shah JP, Hernandez-Prera JC, Ghossein RA, Rodrigo JP, Hartl DM, Olsen KD, Shaha AR, Zafereo M, Suarez C, Nixon IJ, Randolph GW, Mäkitie AA, Kowalski LP, Vander Poorten V, Sanabria A, Guntinas-Lichius O, Simo R, Zbären P, Angelos P, Khafif A, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Papillary Thyroid Cancer-Aggressive Variants and Impact on Management: A Narrative Review. Advances in therapy. 2020 Jul:37(7):3112-3128. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01391-1. Epub 2020 Jun 1

[PubMed PMID: 32488657]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[29]

Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Brito JP. Management of Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea). 2018 Jun:33(2):185-194. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2018.33.2.185. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29947175]

[30]

Sawka AM, Ghai S, Yoannidis T, Rotstein L, Gullane PJ, Gilbert RW, Pasternak JD, Brown DH, Eskander A, Almeida JR, Irish JC, Higgins K, Enepekides DJ, Monteiro E, Banerjee A, Shah M, Gooden E, Zahedi A, Korman M, Ezzat S, Jones JM, Rac VE, Tomlinson G, Stanimirovic A, Gafni A, Baxter NN, Goldstein DP. A Prospective Mixed-Methods Study of Decision-Making on Surgery or Active Surveillance for Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2020 Jul:30(7):999-1007. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0592. Epub 2020 Apr 8

[PubMed PMID: 32126932]

[31]

James BC, Timsina L, Graham R, Angelos P, Haggstrom DA. Changes in total thyroidectomy versus thyroid lobectomy for papillary thyroid cancer during the past 15 years. Surgery. 2019 Jul:166(1):41-47. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.01.007. Epub 2019 Mar 21

[PubMed PMID: 30904172]

[32]

Vargas-Pinto S, Romero Arenas MA. Lobectomy Compared to Total Thyroidectomy for Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review. The Journal of surgical research. 2019 Oct:242():244-251. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.04.036. Epub 2019 May 16

[PubMed PMID: 31103828]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[33]

Gartland RM, Lubitz CC. Impact of Extent of Surgery on Tumor Recurrence and Survival for Papillary Thyroid Cancer Patients. Annals of surgical oncology. 2018 Sep:25(9):2520-2525. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6550-2. Epub 2018 May 31

[PubMed PMID: 29855833]

[34]

Tang J, Kong D, Cui Q, Wang K, Zhang D, Liao X, Gong Y, Wu G. The role of radioactive iodine therapy in papillary thyroid cancer: an observational study based on SEER. OncoTargets and therapy. 2018:11():3551-3560. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S160752. Epub 2018 Jun 19

[PubMed PMID: 29950860]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[35]

Cho SJ, Baek JH, Chung SR, Choi YJ, Lee JH. Thermal Ablation for Small Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2019 Dec:29(12):1774-1783. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0377. Epub 2019 Dec 6

[PubMed PMID: 31739738]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[36]

Chung SR, Baek JH, Choi YJ, Lee JH. Longer-term outcomes of radiofrequency ablation for locally recurrent papillary thyroid cancer. European radiology. 2019 Sep:29(9):4897-4903. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06063-5. Epub 2019 Feb 25

[PubMed PMID: 30805701]

[37]

Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Galdiero MR, Varricchi G, Elia G, Ragusa F, Paparo SR, Benvenga S, Antonelli A. Molecular targets of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in thyroid cancer. Seminars in cancer biology. 2022 Feb:79():180-196. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.11.013. Epub 2020 Nov 26

[PubMed PMID: 33249201]

[38]

Koehler VF, Berg E, Adam P, Weber GL, Pfestroff A, Luster M, Kutsch JM, Lapa C, Sandner B, Rayes N, Fuss CT, Kreissl MC, Hoster E, Allelein S, Schott M, Todica A, Fassnacht M, Kroiss M, Spitzweg C. Real-World Efficacy and Safety of Multi-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Radioiodine Refractory Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2021 Oct:31(10):1531-1541. doi: 10.1089/thy.2021.0091. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 34405734]

[39]

Wagner M, Wuest M, Lopez-Campistrous A, Glubrecht D, Dufour J, Jans HS, Wuest F, McMullen TPW. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy and metabolic remodelling in papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2020 Sep:27(9):495-507. doi: 10.1530/ERC-20-0135. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32590338]

[40]

LiVolsi VA, Merino MJ. Worrisome histologic alterations following fine-needle aspiration of the thyroid (WHAFFT). Pathology annual. 1994:29 ( Pt 2)():99-120

[PubMed PMID: 7936753]

[41]

Baloch ZW, LiVolsi VA. Fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: past, present, and future. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2004 May-Jun:10(3):234-41

[PubMed PMID: 15310542]

[42]

Wong RM, Bresee C, Braunstein GD. Comparison with published systems of a new staging system for papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2013 May:23(5):566-74. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0181. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23106409]

[43]

Loh KC, Greenspan FS, Gee L, Miller TR, Yeo PP. Pathological tumor-node-metastasis (pTNM) staging for papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomas: a retrospective analysis of 700 patients. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1997 Nov:82(11):3553-62

[PubMed PMID: 9360506]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[44]

Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Kihara M, Fukushima M, Higashiyama T, Miya A. Overall Survival of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Patients: A Single-Institution Long-Term Follow-Up of 5897 Patients. World journal of surgery. 2018 Mar:42(3):615-622. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4479-z. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29349484]

[45]

Ulisse S, Baldini E, Lauro A, Pironi D, Tripodi D, Lori E, Ferent IC, Amabile MI, Catania A, Di Matteo FM, Forte F, Santoro A, Palumbo P, D'Andrea V, Sorrenti S. Papillary Thyroid Cancer Prognosis: An Evolving Field. Cancers. 2021 Nov 7:13(21):. doi: 10.3390/cancers13215567. Epub 2021 Nov 7

[PubMed PMID: 34771729]

[46]

Vuong HG, Le HT, Le TTB, Le T, Hassell L, Kakudo K. Clinicopathological significance of major fusion oncogenes in papillary thyroid carcinoma: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Pathology, research and practice. 2022 Dec:240():154180. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2022.154180. Epub 2022 Oct 21

[PubMed PMID: 36306725]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[47]

Lin P, Guo YN, Shi L, Li XJ, Yang H, He Y, Li Q, Dang YW, Wei KL, Chen G. Development of a prognostic index based on an immunogenomic landscape analysis of papillary thyroid cancer. Aging. 2019 Jan 20:11(2):480-500. doi: 10.18632/aging.101754. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30661062]

[48]

Mazzaferri EL, Jhiang SM. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. The American journal of medicine. 1994 Nov:97(5):418-28

[PubMed PMID: 7977430]

[49]

DeGroot LJ, Kaplan EL, McCormick M, Straus FH. Natural history, treatment, and course of papillary thyroid carcinoma. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1990 Aug:71(2):414-24

[PubMed PMID: 2380337]

[50]

Sebastian SO, Gonzalez JM, Paricio PP, Perez JS, Flores DP, Madrona AP, Romero PR, Tebar FJ. Papillary thyroid carcinoma: prognostic index for survival including the histological variety. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2000 Mar:135(3):272-7

[PubMed PMID: 10722027]