Introduction

The piriformis is a flat, pear-shaped muscle located in the gluteal region. This muscle originates from several anatomical locations, namely, the anterior surface of the sacrum, the spinal part of the gluteal muscles, the superior gluteal surface of the ilium near the margin of the greater sciatic notch, the capsule of the adjacent sacroiliac joint, and sometimes, the sacrotuberous ligament.

The piriformis exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic notch before entering the gluteal region. The muscle courses parallel to the posterior margin of the gluteus medius and deep to the gluteus maximus. The tendons of the piriformis, obturator internus, and inferior and superior gemelli fuse before inserting on the superior aspect of the femur's greater trochanter (see Image. Right Femur Anatomy). The piriformis abuts the posterior wall of the pelvis and the posterior wall of the hip joint.[1][2]

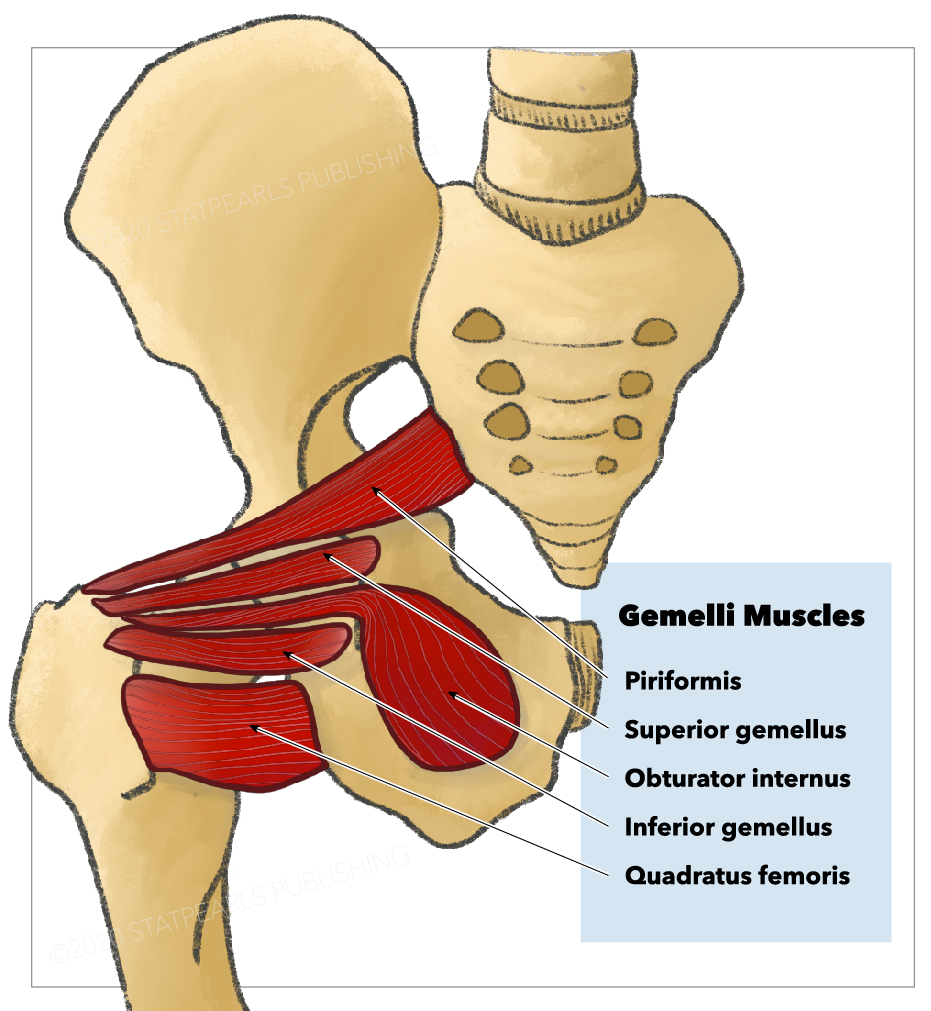

This muscle is one of the 6 short external thigh rotators (see Image. Short External Thigh Rotators). More importantly, the piriformis is a key anatomic structure in that some gluteal nerves and blood vessels are named based on their spatial relationship with this muscle.[3]

This article discusses the piriformis muscle's anatomy and its clinical relevance.

Structure and Function

The piriformis muscle externally rotates the thigh along with the superior and inferior gemelli, quadratus femoris, and obturator internus and externus. Specifically, this muscle laterally rotates the femur during hip extension and abducts the same bone during hip flexion. Femoral abduction is critical during walking, as it shifts the body weight to the opposite side and prevents one from falling.[4][5]The piriformis also serves as a gluteal region landmark. The muscle passes through the greater sciatic foramen, nearly fills the notch, and divides it into superior and inferior segments. Some gluteal nerves and blood vessels derive their names from their anatomic relationship with the piriformis. For example, the superior gluteal nerve and vessels pass superior to the piriformis. The inferior gluteal nerve and vessels transit inferiorly. All the other nerves and blood vessels exit the pelvis inferior to the piriformis.

The sciatic nerve generally exits the pelvis inferior to the piriformis muscle. However, variations occur, and the entire nerve may pass superior to or through the muscle. In other variations, the sciatic nerve may split into its major divisions as high up as the level of the piriformis instead of in the popliteal fossa. The tibial and common peroneal nerves may descend toward the thigh together or separately from either side of the piriformis.

Embryology

The limb buds appear in the 4th week as tiny masses on the ventrolateral body wall. Reciprocal induction of ectoderm and mesoderm forms the limb buds. Each bud is initially composed of a mesenchymal cell mass covered by ectoderm. As the limb bud grows, it receives innervation from the last 4 and first 3 sacral metameres. Grooves appear at the ends of the distal limb as it flattens into footplates. Each footplate rotates to align with the fibula and tibia by the 9th to 12th week. Muscles also start to grow on the flexor and extensor surfaces of the limb at this time.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The piriformis receives its blood supply from the superior gluteal, inferior gluteal, and internal pudendal arteries, all of which are branches of the internal iliac artery.

Nerves

S1 and S2 anterior rami branches innervate the piriformis. The superior gluteal nerve, which innervates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae, exits the pelvis superior to the piriformis. The inferior gluteal nerve, which supplies the gluteus maximus, leaves the pelvis inferior to the piriformis.

Muscles

The piriformis muscle is located partially on the posterior wall of the lesser pelvis and partially posterior to the hip joint. The muscle originates from several locations in the pelvis, passes through the greater sciatic notch, and inserts on the superior aspect of the greater trochanter. The piriformis is intimately associated with the gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, obturator internus, and gemelli muscles.

Physiologic Variants

Piriformis variations may arise as differences in the muscle's innervation patterns or structure. The muscle is supplied only by S2 in some cases and L5 to S2 in others. The sciatic nerve pierces the piriformis in different locations in at least a fifth of the population. The common peroneal nerve may also penetrate the muscle.

The anatomy of the piriformis muscle may not be clearly defined in some individuals because it may have merged with the gluteus medius or gluteus minimus. The piriformis may also have 1 or 2 attachments to the sacrum or capsule of the hip joint in some cases.[6][7]

Surgical Considerations

Piriformis syndrome is a disorder affecting the proximal sciatic nerve, usually presenting with hip and buttock pain due to inflammation. The syndrome is often misdiagnosed and inappropriately treated. Surgical release is only considered in refractory conditions after nonoperative modalities have been exhausted.

The open surgical approach entails the piriformis tendon's complete release from its femoral insertion. Sciatic nerve neurolysis may be performed in tandem when severe fibrosis adversely affects the course of the nerve itself. Post-surgical outcomes generally depend on the condition's chronicity, but the results are often variable. Patients should be counseled about the possibility of symptom persistence after surgery.[8]

Clinical Significance

Piriformis syndrome is a non-discogenic cause of compression neuropathy affecting the sciatic nerve at the level of the ischial tuberosity. The condition is often misdiagnosed and undertreated. Buttock pain is often confused with sciatica, sacroiliitis, lumbar radiculopathy, or trochanteric bursitis. The number of patients with piriformis syndrome has dramatically increased over time. The condition accounts for many cases of partial or total disability. Diagnostic delays lead to chronic pain, hyperesthesia, paresthesias, and muscle weakness.[9][10][11]

Piriformis syndrome presents with gluteal pain and sporadic, referred pain along the sciatic nerve distribution. Prolonged sitting, stair-climbing, stretching, and squatting can worsen the pain. Sciatica is common when the sciatic nerve pierces the muscle. Sciatica symptoms include tingling, numbness, or pain deep in the gluteal area and the regions supplied by the sciatic nerve.

Piriformis syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. MRI and nerve conduction studies help exclude other pathologies. The condition is typically treated conservatively with physical therapy, aiming to eliminate symptoms and improve function. Stretching and motion exercises help relieve the adhesions around the nerve. Corticosteroids and botulinum toxin are sometimes injected into the piriformis muscle. Surgical nerve decompression is the last resort for treating piriformis syndrome.[12]

Other Issues

Pharmacological therapy is often the first line of therapy in patients with piriformis syndrome. The intake of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and prescription analgesics has varying results. Some studies suggest that NSAIDs are better than opiates in relieving pain.

Muscle relaxants have also been used to manage patients with piriformis syndrome. These agents work to some degree but are associated with intolerable adverse effects like drowsiness, dry mouth, and dizziness.

Osteopathic or chiropractic manipulation is often recommended for patients with piriformis syndrome. Both direct and indirect manipulative treatments can improve range of motion and relieve pain.[13]

Steroid injections can decrease the inflammation around the nerve. However, evidence supporting the effectiveness of steroids in treating this condition is lacking. Infection is a steroid complication reported in many studies.[12]