[1]

Todd DJ, Kay J. Gadolinium-Induced Fibrosis. Annual review of medicine. 2016:67():273-91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-063014-124936. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26768242]

[2]

Malikova H. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: the end of the story? Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery. 2019 Aug:9(8):1470-1474. doi: 10.21037/qims.2019.07.11. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31559176]

[3]

Kitajima K, Maeda T, Watanabe S, Ueno Y, Sugimura K. Recent topics related to nephrogenic systemic fibrosis associated with gadolinium-based contrast agents. International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese Urological Association. 2012 Sep:19(9):806-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03042.x. Epub 2012 May 9

[PubMed PMID: 22571387]

[4]

Mathur M,Jones JR,Weinreb JC, Gadolinium Deposition and Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis: A Radiologist's Primer. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2020 Jan-Feb;

[PubMed PMID: 31809230]

[5]

Cowper SE, Su LD, Bhawan J, Robin HS, LeBoit PE. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2001 Oct:23(5):383-93

[PubMed PMID: 11801769]

[6]

Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet (London, England). 2000 Sep 16:356(9234):1000-1

[PubMed PMID: 11041404]

[7]

Daftari Besheli L, Aran S, Shaqdan K, Kay J, Abujudeh H. Current status of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Clinical radiology. 2014 Jul:69(7):661-8. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.01.003. Epub 2014 Feb 28

[PubMed PMID: 24582176]

[8]

Woolen SA,Shankar PR,Gagnier JJ,MacEachern MP,Singer L,Davenport MS, Risk of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis in Patients With Stage 4 or 5 Chronic Kidney Disease Receiving a Group II Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agent: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine. 2020 Feb 1;

[PubMed PMID: 31816007]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[9]

Bertero M, Bainotti S, Comino A, Formica M, Giordano F, Musso L, Palazzini S, Seia Z. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy/nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2009 Jan-Feb:19(1):73-4. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0547. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19171533]

[10]

Shah AH, Olivero JJ. Gadolinium-Induced Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. Methodist DeBakey cardiovascular journal. 2017 Jul-Sep:13(3):172-173. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-13-3-172. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29744004]

[11]

Yee J. Prophylactic Hemodialysis for Protection Against Gadolinium-Induced Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis: A Doll's House. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2017 May:24(3):133-135. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2017.03.007. Epub

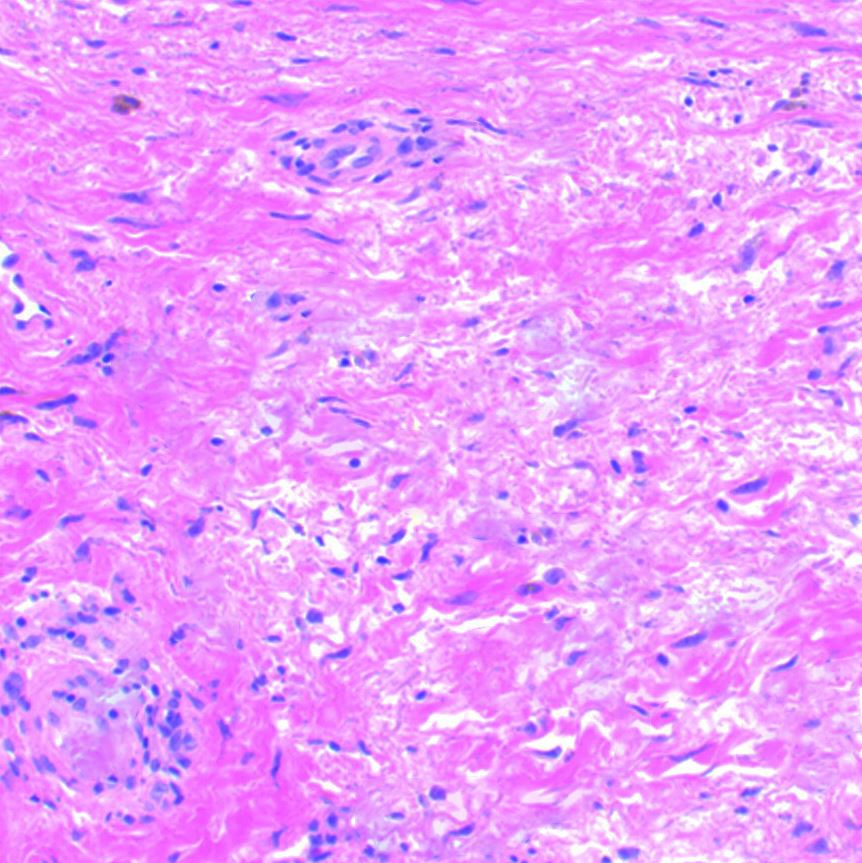

[PubMed PMID: 28501073]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[12]

Marckmann P,Skov L,Rossen K,Dupont A,Damholt MB,Heaf JG,Thomsen HS, Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006 Sep;

[PubMed PMID: 16885403]

[13]

Larson KN, Gagnon AL, Darling MD, Patterson JW, Cropley TG. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis Manifesting a Decade After Exposure to Gadolinium. JAMA dermatology. 2015 Oct:151(10):1117-20. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0976. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26017458]

[14]

Bruce R, Wentland AL, Haemel AK, Garrett RW, Sadowski DR, Djamali A, Sadowski EA. Incidence of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis Using Gadobenate Dimeglumine in 1423 Patients With Renal Insufficiency Compared With Gadodiamide. Investigative radiology. 2016 Nov:51(11):701-705

[PubMed PMID: 26885631]

[15]

Soyer P, Dohan A, Patkar D, Gottschalk A. Observational study on the safety profile of gadoterate meglumine in 35,499 patients: The SECURE study. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2017 Apr:45(4):988-997. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25486. Epub 2016 Oct 11

[PubMed PMID: 27726239]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[16]

Davenport MS, Virtual Elimination of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis: A Medical Success Story with a Small Asterisk. Radiology. 2019 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 31268818]

[17]

Saab G, Cheng S. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a nephrologist's perspective. Hemodialysis international. International Symposium on Home Hemodialysis. 2007 Oct:11 Suppl 3():S2-6

[PubMed PMID: 17897106]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[18]

Reimer P, Vosshenrich R. [Contrast agents in radiology: current agents approved, recommendations, and safety aspects]. Der Radiologe. 2013 Feb:53(2):153-64. doi: 10.1007/s00117-012-2429-6. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23340684]

[19]

Do C, Drel V, Tan C, Lee D, Wagner B. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis Is Mediated by Myeloid C-C Chemokine Receptor 2. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2019 Oct:139(10):2134-2143.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1145. Epub 2019 Apr 9

[PubMed PMID: 30978353]

[20]

Papanicolas I,Woskie LR,Jha AK, Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries. JAMA. 2018 Mar 13;

[PubMed PMID: 29536101]

[21]

Attari H, Cao Y, Elmholdt TR, Zhao Y, Prince MR. A Systematic Review of 639 Patients with Biopsy-confirmed Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. Radiology. 2019 Aug:292(2):376-386. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019182916. Epub 2019 Jul 2

[PubMed PMID: 31264946]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[22]

Perez-Rodriguez J, Lai S, Ehst BD, Fine DM, Bluemke DA. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: incidence, associations, and effect of risk factor assessment--report of 33 cases. Radiology. 2009 Feb:250(2):371-7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2502080498. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19188312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[23]

Goldstein KM, Lunyera J, Mohottige D, Amrhein TJ, Alexopoulos AS, Campbell H, Cameron CB, Sagalla N, Crowley MJ, Dietch JR, Gordon AM, Kosinski AS, Cantrell S, Williams Jr JW, Gierisch JM. Risk of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis after Exposure to Newer Gadolinium Agents. 2019 Oct:():

[PubMed PMID: 32687278]

[24]

Deo A,Fogel M,Cowper SE, Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a population study examining the relationship of disease development to gadolinium exposure. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2007 Mar

[PubMed PMID: 17699423]

[25]

Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: predictor of early mortality and association with gadolinium exposure. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2007 Oct:56(10):3433-41

[PubMed PMID: 17907148]

[26]

Khor LK, Tan KB, Loi HY, Lu SJ. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in a patient with renal failure demonstrating a "reverse superscan" on bone scintigraphy. Clinical nuclear medicine. 2013 Mar:38(3):203-4. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31827a22ae. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23354034]

[27]

Elmholdt TR, Olesen AB, Jørgensen B, Kvist S, Skov L, Thomsen HS, Marckmann P, Pedersen M. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in Denmark--a nationwide investigation. PloS one. 2013:8(12):e82037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082037. Epub 2013 Dec 9

[PubMed PMID: 24349178]

[28]

Amet S,Launay-Vacher V,Clément O,Frances C,Tricotel A,Stengel B,Gauvrit JY,Grenier N,Reinhardt G,Janus N,Choukroun G,Laville M,Deray G, Incidence of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients undergoing dialysis after contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium-based contrast agents: the Prospective Fibrose Nephrogénique Systémique study. Investigative radiology. 2014 Feb

[PubMed PMID: 24169070]

[29]

Lim YJ, Bang J, Ko Y, Seo HM, Jung WY, Yi JH, Han SW, Yu MY. Late Onset Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis in a Patient with Stage 3 Chronic Kidney Disease: a Case Report. Journal of Korean medical science. 2020 Sep 7:35(35):e293. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e293. Epub 2020 Sep 7

[PubMed PMID: 32893521]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[30]

Drel VR, Tan C, Barnes JL, Gorin Y, Lee DY, Wagner B. Centrality of bone marrow in the severity of gadolinium-based contrast-induced systemic fibrosis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2016 Sep:30(9):3026-38. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500188R. Epub 2016 May 24

[PubMed PMID: 27221979]

[31]

McNeill AM, Barr RJ. Scleromyxedema-like fibromucinosis in a patient undergoing hemodialysis. International journal of dermatology. 2002 Jun:41(6):364-7

[PubMed PMID: 12100695]

[32]

Mackay-Wiggan JM,Cohen DJ,Hardy MA,Knobler EH,Grossman ME, Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (scleromyxedema-like illness of renal disease). Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003 Jan

[PubMed PMID: 12522371]

[33]

Kucher C, Xu X, Pasha T, Elenitsas R. Histopathologic comparison of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and scleromyxedema. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2005 Aug:32(7):484-90

[PubMed PMID: 16008692]

[34]

Yoldez H, Ahlem B, Abderrahim E, Faten Z, Soumaya R. [Nephrogenic fibrosing dermatosis: From clinic to microscopy]. Nephrologie & therapeutique. 2018 Feb:14(1):47-49. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2017.02.017. Epub 2017 Nov 26

[PubMed PMID: 29239786]

[35]

Boyd AS, Zic JA, Abraham JL. Gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2007 Jan:56(1):27-30

[PubMed PMID: 17109993]

[36]

Ruiz-Genao DP,Pascual-Lopez MP,Fraga S,Aragüés M,Garcia-Diez A, Osseous metaplasia in the setting of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2005 Feb

[PubMed PMID: 15606678]

[37]

Hubbard V, Davenport A, Jarmulowicz M, Rustin M. Scleromyxoedema-like changes in four renal dialysis patients. The British journal of dermatology. 2003 Mar:148(3):563-8

[PubMed PMID: 12653751]

[38]

Levine JM, Taylor RA, Elman LB, Bird SJ, Lavi E, Stolzenberg ED, McGarvey ML, Asbury AK, Jimenez SA. Involvement of skeletal muscle in dialysis-associated systemic fibrosis (nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy). Muscle & nerve. 2004 Nov:30(5):569-77

[PubMed PMID: 15389718]

[39]

Zhang R, Rose WN. Photopheresis Provides Significant Long-Lasting Benefit in Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis. Case reports in dermatological medicine. 2017:2017():3240287. doi: 10.1155/2017/3240287. Epub 2017 Jun 12

[PubMed PMID: 28695022]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[40]

Kowal-Bielecka O,Fransen J,Avouac J,Becker M,Kulak A,Allanore Y,Distler O,Clements P,Cutolo M,Czirjak L,Damjanov N,Del Galdo F,Denton CP,Distler JHW,Foeldvari I,Figelstone K,Frerix M,Furst DE,Guiducci S,Hunzelmann N,Khanna D,Matucci-Cerinic M,Herrick AL,van den Hoogen F,van Laar JM,Riemekasten G,Silver R,Smith V,Sulli A,Tarner I,Tyndall A,Welling J,Wigley F,Valentini G,Walker UA,Zulian F,Müller-Ladner U, Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2017 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 27941129]

[41]

Elmholdt TR, Buus NH, Ramsing M, Olesen AB. Antifibrotic effect after low-dose imatinib mesylate treatment in patients with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: an open-label non-randomized, uncontrolled clinical trial. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2013 Jun:27(6):779-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04398.x. Epub 2011 Dec 20

[PubMed PMID: 22188390]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[42]

Panesar M, Yacoub R. What is the role of renal transplantation in a patient with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis? Seminars in dialysis. 2011 Jul-Aug:24(4):373-4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.00913.x. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21851392]

[43]

Cuffy MC, Singh M, Formica R, Simmons E, Abu Alfa AK, Carlson K, Girardi M, Cowper SE, Kulkarni S. Renal transplantation for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2011 Mar:26(3):1099-101. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq693. Epub 2010 Nov 15

[PubMed PMID: 21079195]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[44]

Panesar M,Banerjee S,Barone GW, Clinical improvement of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after kidney transplantation. Clinical transplantation. 2008 Nov-Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 18713261]

[45]

Schmook T, Budde K, Ulrich C, Neumayer HH, Fritsche L, Stockfleth E. Successful treatment of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy in a kidney transplant recipient with photodynamic therapy. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2005 Jan:20(1):220-2

[PubMed PMID: 15632355]

[46]

Kafi R, Fisher GJ, Quan T, Shao Y, Wang R, Voorhees JJ, Kang S. UV-A1 phototherapy improves nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. Archives of dermatology. 2004 Nov:140(11):1322-4

[PubMed PMID: 15545539]

[47]

Chung HJ, Chung KY. Nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy: response to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. The British journal of dermatology. 2004 Mar:150(3):596-7

[PubMed PMID: 15030351]

[48]

Wahba IM,White K,Meyer M,Simpson EL, The case for ultraviolet light therapy in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy--report of two cases and review of the literature. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2007 Feb;

[PubMed PMID: 17124282]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[49]

Yerram P, Saab G, Karuparthi PR, Hayden MR, Khanna R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a mysterious disease in patients with renal failure--role of gadolinium-based contrast media in causation and the beneficial effect of intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2007 Mar:2(2):258-63

[PubMed PMID: 17699422]

[50]

Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2016 Jul 1:311(1):F1-F11. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00166.2016. Epub 2016 May 4

[PubMed PMID: 27147669]

[51]

He A, Kwatra SG, Zampella JG, Loss MJ. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: fibrotic plaques and contracture following exposure to gadolinium-based contrast media. BMJ case reports. 2016 Apr 12:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-214927. Epub 2016 Apr 12

[PubMed PMID: 27073153]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[52]

Maripuri S,Johansen KL, Risk of Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents in Chronic Kidney Disease-Is Zero Good Enough? JAMA internal medicine. 2020 Feb 1;

[PubMed PMID: 31816006]

[53]

Mehdi A, Taliercio JJ, Nakhoul G. Contrast media in patients with kidney disease: An update. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2020 Nov 2:87(11):683-694. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.20015. Epub 2020 Nov 2

[PubMed PMID: 33139262]

[54]

Weinreb JC, Rodby RA, Yee J, Wang CL, Fine D, McDonald RJ, Perazella MA, Dillman JR, Davenport MS. Use of Intravenous Gadolinium-based Contrast Media in Patients with Kidney Disease: Consensus Statements from the American College of Radiology and the National Kidney Foundation. Radiology. 2021 Jan:298(1):28-35. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202903. Epub 2020 Nov 10

[PubMed PMID: 33170103]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[55]

Cheong BY, Muthupillai R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a concise review for cardiologists. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2010:37(5):508-15

[PubMed PMID: 20978560]

[56]

Lunyera J,Mohottige D,Alexopoulos AS,Campbell H,Cameron CB,Sagalla N,Amrhein TJ,Crowley MJ,Dietch JR,Gordon AM,Kosinski AS,Cantrell S,Williams JW Jr,Gierisch JM,Ear B,Goldstein KM, Risk for Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis After Exposure to Newer Gadolinium Agents: A Systematic Review. Annals of internal medicine. 2020 Jul 21;

[PubMed PMID: 32568573]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[57]

Shankar PR, Davenport MS. Risk of Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis in Stage 4 and 5 Chronic Kidney Disease Following Group II Gadolinium-based Contrast Agent Administration: Subanalysis by Chronic Kidney Disease Stage. Radiology. 2020 Nov:297(2):447-448. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201492. Epub 2020 Aug 18

[PubMed PMID: 32808890]