Continuing Education Activity

The metacarpals form the osseous base of the complex lever system of flexor and extensor tendons of the hand. Understandably, fractures of the metacarpals disrupt this mechanism causing significant disability for the active or working patient and can come about from several different mechanisms. Due to the complexity of its form and function, orthopedic surgeons and other clinical providers must be able to recognize metacarpal fractures readily and treat these injuries in a timely fashion to avoid complications. This activity will provide the reader with the basics for identifying, treating, and managing complications of metacarpal fractures. It will also go in-depth on the decision-making behind non-operative versus operative treatment, including its benefits and pitfalls.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of metacarpal fractures.

- Review the proper evaluation of metacarpal fractures.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for metacarpal fractures and when to use non-operative versus operative treatment.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance care delivery for patients with metacarpal fractures.

Introduction

The metacarpals form the osseous base of the complex lever system of flexor and extensor tendons of the hand. Understandably, fractures of the metacarpals disrupt this mechanism causing significant disability for the active or working patient and can come about from several different mechanisms.[1] Metacarpal fractures are common in the general population, with relative propensity seen in contact-sport athletes (e.g., boxers and football players) and manual laborers.[2] Due to the complexity of its form and function, orthopedic surgeons and other clinical providers must be able to recognize metacarpal fractures readily and treat these injuries in a timely fashion to avoid complications.

Etiology

Metacarpal fractures can occur in various settings but most commonly occur as a result of direct trauma.[3] As metacarpal bones are superficial, these commonly get fractured when the hand is used for evasive action.[4] For metacarpal shaft fractures, direct blows to the dorsum of the hand can result in transverse fractures with varying degrees of comminution depending on the velocity of the injury.[1][5][6] Oblique fractures can be seen after rotational and axial loads while bending forces with axial loads produce a butterfly fragment with differing degrees of comminution depending on the amount of force imparted by the injury.[6][5][7]

Perhaps the most well-known fracture type is the so-called "boxer's fracture," implying a fracture of the neck of the fifth metacarpal with a volar displacement that presents in 20% of all hand fractures.[8] These neck fractures often result from a combination of axial load with a slight flexion moment, which causes the neck to fracture and displace volarly. Similarly, intraarticular fractures of the metacarpal base also arise from axial loads and can lead to carpometacarpal joint arthritis.

Epidemiology

While the most common fracture types of the upper extremity are distal radius followed by phalangeal fractures, metacarpal fractures are the third most common fracture. They are the second most common hand fractures. Metacarpal fractures account for approximately 40% of all hand injuries.[9][7] Moreover, in patients in the 18 to 34-year-old age distribution, metacarpal fractures are the most common injury in the hand, with an incidence of 12.5 patients per 10000.[10] Gender appears to factor in these injuries, as 76% of all metacarpal injuries occur in males.[3]

The incidence rate of fracture associated with each digit's metacarpal bone increases from the radial to the ulnar side. The incidence rate of 2nd metacarpal fractures is lower than that of 5th metacarpal fractures.[11] The metacarpal fractures may occur as isolated fractures, associated with other metacarpal fractures, or with other bony injuries.[4]

History and Physical

When evaluating a patient with a suspected metacarpal fracture, looking for the hallmark signs of swelling, ecchymosis, tenderness to palpation, and pain with range of motion are expected to be seen. However, more specific signs of metacarpal fractures, including loss of knuckle height, digit malrotation, or digit crossing over ("scissoring"), should clue the physician into evaluating for an injury to the metacarpals. These signs, combined with a thorough history, will aid the practitioner in deciding to assess further for fracture.[4] It is essential to identify rotational deformity in suspected metacarpal fractures. The rotational deformity can be diagnosed by observing for overriding of the fingers at the time of presentation.[4] Also, hand dominance, current working status, participation in athletic activities, and any prior history of fracture need to be evaluated.[7]

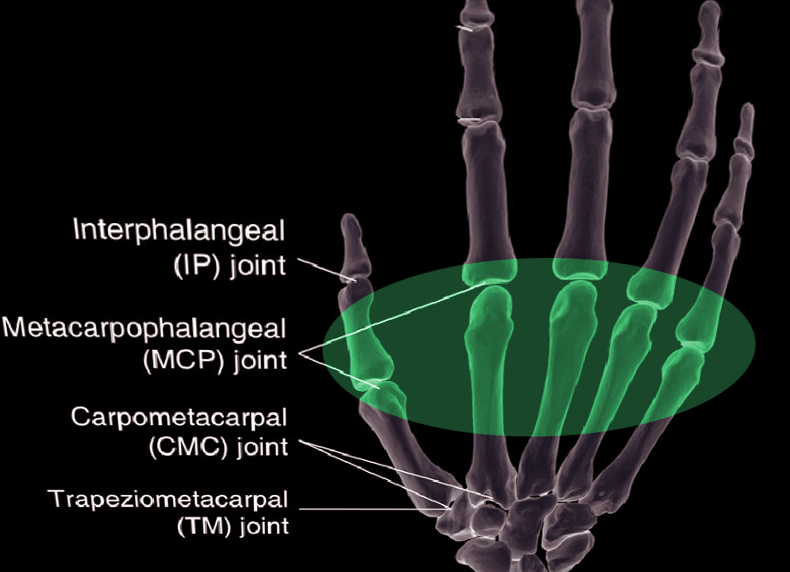

Other clinical pearls include evaluating the integrity of the skin. The latter is extremely important to rule out "fight bite" injuries, and dorsal wounds over the MCP joint are traumatic arthrotomies and open fracture patterns until proven otherwise.[12][13] Also, dorsal injuries often correlate with extensor tendon lacerations, which should also be ruled out during the evaluation.[14][15]

Evaluation

Imaging of metacarpal fractures should include standard PA and lateral as well as an oblique view to further examine the ulnar-most digits. An external rotation oblique film allows for visualization of the fourth and fifth MC fractures and CMC dislocations, while an internal rotation oblique film allows for visualization of the second and third MC and CMC fractures/dislocations.[9]

Classification of these injuries has its basis in basic fracture characteristics. Examples include transverse, oblique, spiral, displaced, or comminuted. Location is also important and is usually divided into the distal aspect, the neck or head, the shaft, and the base, the most proximal portion. It is also important to consider rotational and shortening deformities, multiple metacarpal fractures, and the amount of initial displacement. These can be indicators of unstable fractures that will necessitate operative fixation.[1][16] CT is sometimes necessary for the base of metacarpal fractures to check for any intra-articular displacement and determine if surgery is needed.[17]

As the loss of metacarpal height becomes more severe, the extension lag of the digit in question becomes more significant. Metacarpal-phalangeal (MCP) joints show an average of 20 degrees of hyperextension. Still, for every 2 mm of metacarpal height that is lost, there are a concomitant 7 degrees of extensor lag at the MCP joint.[12] Because of the natural hyperextension at the MCP, a total of 5 to 6 mm of metacarpal height (21 to 30 degrees of extensor lag) is tolerable before detrimental effects occur.[18] In addition to simple fracture characteristics, the anatomical cascade of the metacarpals should play into the physician’s diagnosis. For instance, the index and long fingers are limited in motion relative to the ulnar most digits due to their attachment to the trapezoid and capitate and can only tolerate 10 to 15 degrees of angulation. However, the ring and small finger articulation at the hamate permit a greater range of motion and, therefore, may tolerate more angulation of 30 to 45 degrees in the ring and up to 50 in the small finger.[1][19]

Treatment / Management

When considering the treatment of these fractures, the clinician has a wide range of options. While non-operative treatment is certainly an option for those fractures in an acceptable pattern or alignment, fractures requiring operative fixation have several available options. Most commonly seen are percutaneous wires, intramedullary fixation, and open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) with plate fixation or lag screws is a common approach. The goal of treatment should be to begin early range of motion exercises 2 to 4 weeks postoperatively to avoid hand stiffness and to return to normal activities as soon as possible.

For the decision to pursue non-operative treatment, we must revisit the concept of metacarpal stability. The stability of the metacarpal is determined by both physical and radiographic evaluation focusing on the loss of height, scissoring of the digit, normal digit cascade, multiple fractures, and angulation of the fracture specific to the digit. The clinician should attempt non-operative treatment if the fracture falls within acceptable ranges. However, a reduction is necessary if fractures are outside this range and non-operative treatment is preferred.[4]

In general, reductions of metacarpal fractures, regardless of location, should begin an appropriate anesthetic application with axial traction to disimpact the fracture and dorsal pressure on the hand, as most fractures displace with dorsal angulation; this is especially true for fractures of the metacarpal shaft. For metacarpal neck fractures, flexion of MCP joints to 90 degrees allows for tightening of the MCP ligaments allowing greater control of the distal fragment. Particular attention should be paid to neck fractures in the small finger as these injuries tend to be more and may require fixation.[20] For intraarticular injuries, axial traction and dorsal pressure are also used to both disimpact and stabilize comminuted articular fragments. After reduction is completed and verified on imaging, the hand must be immobilized in the “intrinsic plus” position, such that there is flexion of the MCP joints to 90 degrees with full extension of interphalangeal joints; this is done to put the capsule and ligaments on a stretch to prevent any contractures while immobilized. This positioning is for 2 to 3 weeks with interval plain film evaluation to detect loss of reduction.[21]

If the reduction is maintained, patients may be graduated to buddy tapping of the involved digit and begin range of motion exercises until obtaining clinical union. However, even with a pristine reduction, these fractures may displace during treatment and, in doing so, will require fixation in most cases.

For fractures that have either failed non-operative treatment, are open, or are outside the accepted criteria previously mentioned, either closed or open reduction with internal fixation will be the treatment of choice. Height, rotation, and proper angulation must be achieved to restore hand motion and grip strength. Management of open fractures should always begin with the rapid administration of IV antibiotics, tetanus prophylaxis, and early irrigation and debridement.

Metacarpal head fractures are uncommon injuries, but most arise due to direct trauma and require operative fixation when there is a significant defect in the articular surface or instability is detected on the exam.[22] Fractures with large articular pieces are readily fixed with small screws, while condylar plates are useful in injuries with metaphyseal extension. For those fractures that are extensively comminuted, K-wire fixation is appropriate, as small fragments do not provide adequate screw purchase. However, for both of these options, the practitioner must be careful not to violate the joint and must be immobilized for two weeks.[19]

For metacarpal neck fractures, intramedullary or trans-metacarpal K-wires are the mainstay of treatment to help control angulation and restore height. These fixation options, however, don’t readily control rotation, even with post-operative immobilization. Contralateral hand films can aid careful examination of rotation to ensure proper alignment. A downside to intramedullary K-wire placement is the necessity for a secondary procedure to remove hardware. Other options include intramedullary headless screws, which still present the issue of rotational control postoperatively, but do not necessitate a second procedure for hardware removal.[23] With either option, brief post-operative immobilization is in order, followed by early ROM exercises. Recent studies have shown radiographic union on an average of 49 days with an average return to daily activities at 4 to 6 weeks. Recently, a novel intraoperative kickstand technique has been reported to reduce angulated metacarpal neck fractures before retrograde headless intramedullary screw fixation. [24]

The most common fracture site in the metacarpal is the shaft, and those with oblique and spiral fracture types have a higher likelihood of rotational deformity, requiring operative fixation. Primary options for fixation of these injuries include intramedullary K-wires, plate and screws, and, more recently, headless intramedullary compression screws. Percutaneous K-wires provide a minimally invasive approach. Intramedullary K-wires allow for length stability and can be supplemented with trans-metacarpal K-wires to achieve rotational stability as well, but are inferior in stability to plates and screws. Plates and screws can be viable in multiple modes for different fracture types for more rigid fixation. For oblique and spiral, lag screws can be applied with neutralization plating, while transverse fractures should have plates used in compression mode. This approach allows for more inherent stability and earlier ROM exercises in the post-operative period with favorable outcomes in ROM and a return to activity.[1] However, recent studies and literature reviews have shown that while complication rates in both methods are similar, functional impairment requiring reoperation is significantly higher in patients undergoing ORIF with plate fixation compared to percutaneous pinning.[16][25]

Metacarpal base fractures can present as both extra and intra-articular injuries. While extra-articular fractures are mostly seen independent of other injuries, intra-articular fractures can present with concomitant carpometacarpal joint dislocation, especially in the ring and small fingers.[26] For extra-articular base fractures, many of them occur in the meta-diaphyseal junction and can be sufficiently fixated percutaneously with K-wires to avoid devascularizing fracture fragments, but sometimes require an open approach with plate and screw fixation for direct visualization in complex fracture types. For intra-articular fractures, percutaneous pinning is again the preferred treatment method for the ring and small fingers. However, for the index and long fingers, thought must be given to the deep palmar arterial arch and the motor branch of the ulnar nerve.

Because these vital structures are close to the long finger metacarpal base, open reduction with plate and screw application should be undertaken to preserve them. Again, rigid fixation does provide the option for an early range of motion but risks anatomic structures and may damage fracture fragments. Several studies in the past have found near-equivalent outcomes for non-operative management and surgical treatment. Nearly half of the patients treated with surgical means had residual pain after their procedure, comparable to those treated with reduction and splinting.[27][28] Because of these findings, care much be taken in selecting which patients will benefit from either surgical or non-operative management with intra-articular base fractures.

The thumb metacarpal deserves special consideration, given the relative lack of interossei and deep intermetacarpal ligament support. Fractures deform dictated by the three muscles providing the deforming forces at the base of the thumb. Despite the thumb tolerating more angulation than other metacarpals due to its higher mobility, an apex dorsal angulation of over 30 degrees often fares poorly with non-operative management. Indications for closed reduction and thumb spica casting include extra-articular fracture, less than 30 degrees of angulation following closed reduction, and non-displaced (or less than 1 mm displacement) of an intra-articular fracture (i.e., Bennet fracture). Intra-articular fractures (Bennett – 2 part and Rolando – 3 part fracture patterns) most commonly require surgical fixation. The joint surface must be reduced to avoid long-term post-traumatic deformity and articular cartilage degeneration.[17][29]

Open fractures should have treatment with local wound care and antibiotics. Although controversial, healthcare providers are to utilize best judgment practices regarding timely debridement with removal of any dirt/debris and primary versus secondary wound closure in the acute setting. For example, management of fight bite injuries is best with formal surgical irrigation and debridement of the MCP joint, given the high risk of infection with local wound care in the emergency department only. When in doubt, clinicians should consult the hand surgical service on call at the institution.[7]

Post-operative patients require immobilization in the intrinsic plus position, as described previously, to reduce joint capsule contraction. Education to elevate their affected extremity as often as possible is also important, as dependent edema can significantly increase pain and limit range of motion, thus creating a stiff hand. For patients with plate and screw fixation, immobilization should cease at the first post-op visit, and gentle range of motion exercises should commence. For those patients who undergo percutaneous fixation, early ROM can be difficult due to soft tissue adhesions to the K-wire but should require implementation once a clinical union is obtained, commonly at 3 to 6 weeks.[21]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes the neighboring bony and soft tissue injuries, including muscular, tendinous, and ligamentous injuries. Identifying fractures is possible by obvious deformity to the hand but is most readily identified with imaging.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the exact type of fracture, the method of fixation, and any complications arising in the recovery period. Overall, when appropriately managed, the prognosis is good for metacarpal fractures. However, the patient's expectations must be considered while managing these fractures. While there are many different options for the fixation of metacarpal fractures depending on their location, operative treatment lends to good outcomes.

Complications

Complications of metacarpal fractures are similar to those of most fractures, including nonunion, malunion, hand stiffness, and infection. For post-surgical patients, infections require treatment with antibiotics, hardware removal, and infected tissue debridement. Depending on the timing of the infection, skeletal fixation or reconstruction may require postponement until the resolution of the infection.[1]

Stiffness can be detrimental in patients with hand fractures, especially when they occur in the dominant hand. For patients undergoing splinting or percutaneous pinning, exercises should begin at four weeks or as soon as achieving clinical union. However, those with plate fixation can be exercised immediately upon the removal of the sutures, which commonly occurs at the first post-op visit.[1]

Metacarpal nonunions are rare and occur in as few as 0.2 to 0.7% of patients.[30] A clinical union is normally seen in 3 to 6 weeks from injury if treated non-operatively or from the time of surgery in operatively treated patients.[1] Delayed union is the progressive absence of bridging bone across the fracture site with persistent pain and can be due to loss of bone stock, poor immobilization, or infection. Nonunion is diagnosed with similar findings but at nine months. The most common occurrence of non or delayed union cases after surgery is in patients treated with K-wire fixation.[31][30] Treatment should include bone grafting with rigid fixation with plates and screws to disallow motion at the fracture site.[31]

Malunion can be best observed by physical examination and plain films looking at knuckle height or abnormal digit rotation and scissoring and can lead to post-traumatic arthritis in articular fractures. For rotational or length deformities, corrective osteotomies can help to restore proper digit cascade, and for articular malunions, arthroplasty and fusion are two salvage options to attain acceptable outcomes.[1]

As with any surgical procedure, damage to soft tissues, nerves, or arteries is possible. Care must be taken to preserve these structures, especially each neurovascular bundle and the dorsal sensory nerves in the hand, when performing dorsal approaches to the metacarpals for ORIF.[1]

Plate fixation runs a risk of tendon irritation and, in the worst cases, rupture. If plates are used, periosteal closure should be done whenever possible to reduce this risk. Healthcare providers should evaluate extensor tendon function following operative and nonoperative management of these injuries.[21]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

While there are many different options for the fixation of metacarpal fractures depending on their location, operative treatment lends to good outcomes. For those treated by closed means with K-wire, fixation outcomes tend to show more mobility than plate fixation, but other than mobility, DASH scores, grip strength, and pain are similar.[32] Even though these outcome measures were for fifth metacarpal necks due to their overabundance, it is reasonable to assume the results would be interchangeable with metacarpals 1 through 4. However, as with all intramedullary fixation, the surgeon must be cognizant of potential malrotation at the fracture site to avoid malunion. The goal of rehabilitation is a full range of motion of the fingers and hand. Hand exercises with light resistance, such as rubber bands or squeeze balls, are essential if there is scarring or extensor lag develops.[33]

Deterrence and Patient Education

As the most common cause of these injuries relates to sporting and work injuries, athletes should receive education in safety for their given sport and proper safety protocols for the working patient.[1] Sportspersons should be particularly briefed about the implications of such injuries and their prevention. When left untreated or inappropriately managed, they can lead to significant morbidity.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Metacarpal fractures have several different presentations and can have detrimental effects on the hand if not treated correctly; thus, they require the efforts of an interprofessional team. Classifying these injuries appropriately will give the clinician the tools to choose the correct treatment plan and, if necessary, engage in operative fixation. If there is any ambiguity, an orthopedic specialist should consult on the case. Orthopedic specialty nurses can also significantly contribute to these cases by assisting with operative and non-operative reduction. The nurse can also answer patient questions, perform appropriate follow-up, and inform the treating clinician of any concerns. All interprofessional team members should maintain accurate and updated patient records, so all caregivers have accurate patient data. Being vigilant throughout the treatment process will also help to identify complications to these injuries to provide the best possible outcome for the patient for every level of health care provider on the interprofessional team. The interprofessional approach will yield optimal patient results with the fewest adverse events. [Level 5]