Continuing Education Activity

The latissimus dorsi flap is a highly versatile reconstructive option used in head, neck, torso, and breast reconstruction surgeries. Surgeons harvest the flap from the latissimus dorsi muscle, which is richly vascularized by the thoracodorsal vessels. This ensures flap viability and enables its use as a pedicled or free tissue transfer method. This versatility provides ample soft tissue coverage for large defects with excellent skin color and texture match, making it particularly advantageous for aesthetic reconstruction. Early recognition and intervention can often salvage the flap despite potential complications such as flap failure or vascular compromise. Overall, the latissimus dorsi flap is a valuable tool in the armamentarium of reconstructive surgeons, offering effective solutions for complex defects.

Recent advancements have also extended the use of the latissimus dorsi flap to neophallus construction for transgender individuals, showcasing its evolving versatility. This activity provides clinicians with a comprehensive understanding of using the latissimus dorsi flap in reconstructive surgery, emphasizing flap harvest, transfer techniques, perioperative management, patient selection, and postoperative care strategies. This activity enables interdisciplinary healthcare professionals to refine their skills in managing diverse clinical scenarios, emphasizing the indispensable role of the latissimus dorsi flap in modern surgical practice. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and communication, this activity equips healthcare professionals to effectively incorporate the latissimus dorsi flap into their practice, leading to enhanced patient-centered care and improved surgical outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify appropriate candidates for latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction based on the patient's medical history, physical examination, and imaging studies.

Implement preoperative optimization strategies, including smoking cessation, nutritional assessment, and wound care preparation, to enhance outcomes for patients undergoing latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction.

Select appropriate adjunctive procedures, such as nerve coaptation or skin grafting, and appropriate postoperative monitoring protocols in latissimus dorsi flap surgeries.

Collaborate with multidisciplinary healthcare professionals, including plastic surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists, to develop comprehensive treatment plans and optimize patient outcomes.

Introduction

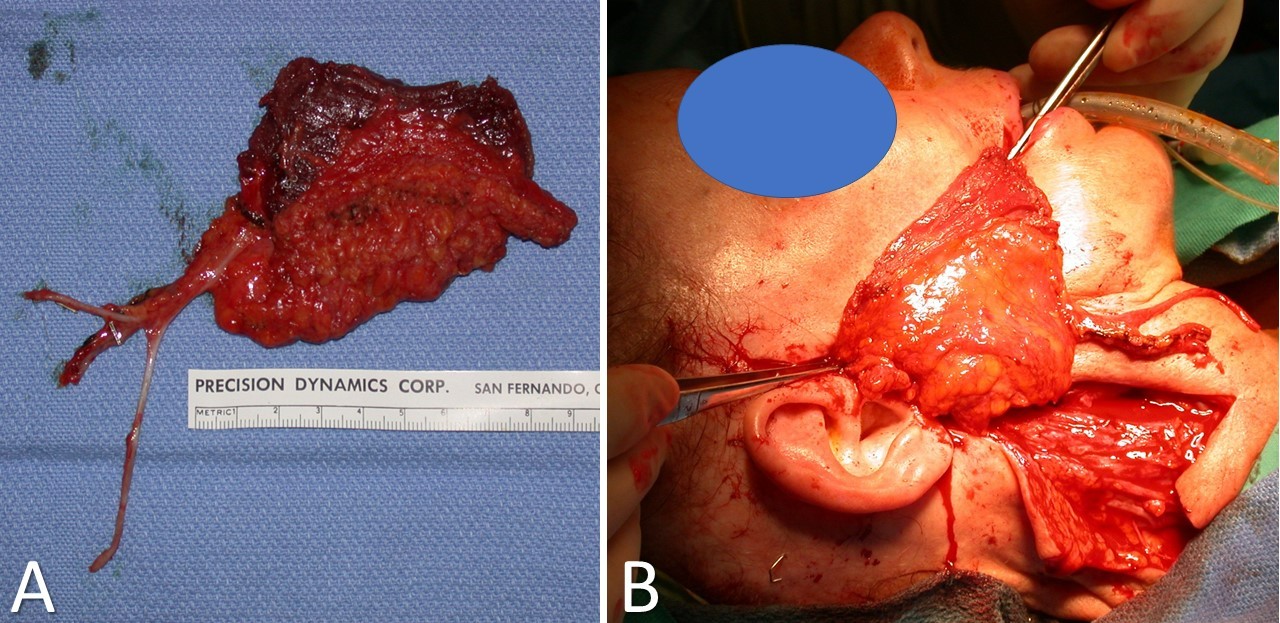

The latissimus dorsi flap, whether myocutaneous or myofascial, is a highly versatile reconstructive option used in head, neck, torso, and breast reconstruction surgeries, providing a versatile solution to a wide range of reconstructive challenges (see Image 3. Latissimus Dorsi Myocutaneous Free Flap and Image 4. Latissimus Dorsi Myofascial Free Flap).[1][2][3] Surgeons harvest the flap from the latissimus dorsi muscle, which is richly vascularized by the thoracodorsal vessels. This ensures flap viability and enables its use as both a pedicled and free tissue transfer method. This flap provides an abundant source of pliable soft tissue, a quality often lacking in alternative flap options. Moreover, the myocutaneous version of the latissimus dorsi flap is designed to include skin and subcutaneous tissue, providing extra bulk as needed, thereby enhancing its versatility across various clinical scenarios.[4] With minimal absolute contraindications and remarkable versatility, this flap presents itself as an indispensable tool in the arsenal of reconstructive surgeons, offering effective solutions for complex defects.

In postmastectomy breast reconstruction, the pedicled latissimus dorsi transfer is commonly used, and its application also extends to free functional muscle transfer for facial reanimation.[5][6][7] Whether utilized as muscle alone or including skin, the pedicled latissimus dorsi flap can effectively address chest or neck defects without tension. This approach is particularly advantageous for women with neck defects, avoiding potential breast deformities linked with pectoralis flap reconstruction. In extensive cases, surgeons may harvest a mega flap that includes the latissimus dorsi and parascapular soft tissue, along with the subscapular artery, circumflex scapular, and thoracodorsal branches. These mega flaps may necessitate the inclusion of scapular bone, rib, and the serratus anterior muscle for reconstruction purposes.[8]

Recent advancements in surgical techniques have extended the use of the latissimus dorsi flap beyond traditional reconstructive applications, exemplified by its use in neophallus construction for transgender individuals.[3] This innovative adaptation underscores the flap's remarkable versatility and ability to address diverse anatomical and functional requirements. Consequently, the latissimus dorsi flap continues to evolve, broadening its range of applications and confirming its crucial role in modern surgical practice.

Anatomy and Physiology

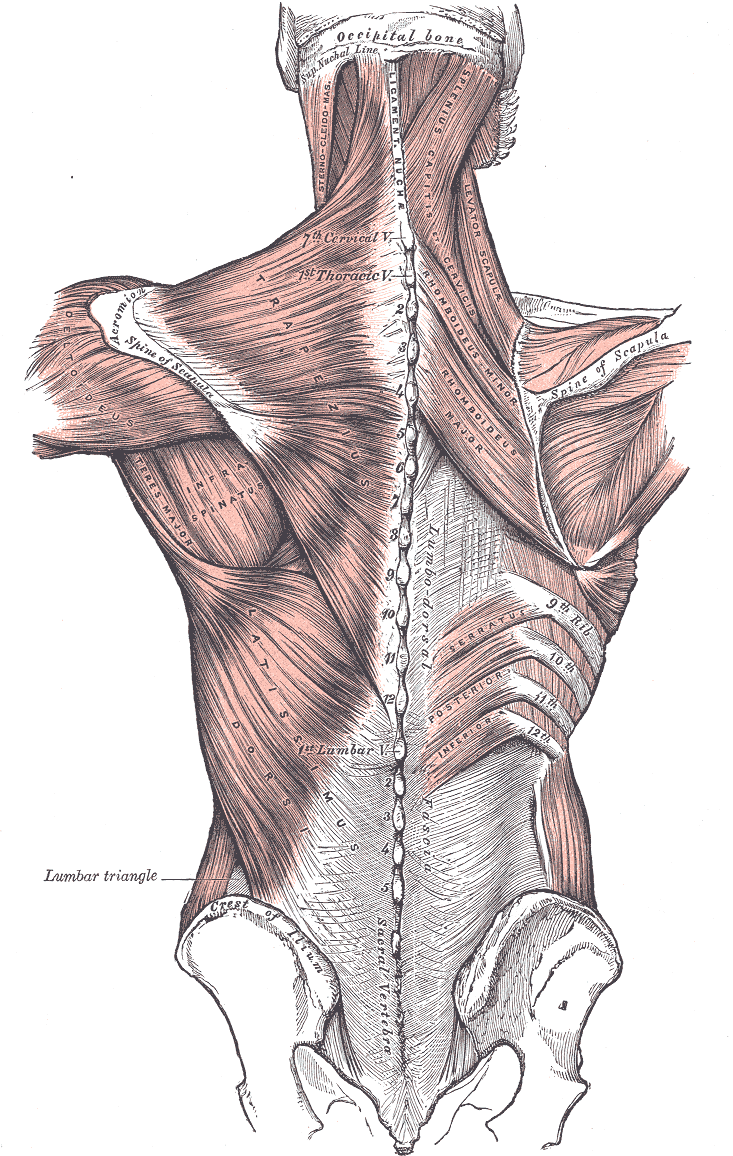

The latissimus dorsi muscle is one of the body's strongest muscles, which boasts a significant surface area, measuring up to 20×40 cm. This muscle originates from the spine and ilium and extends across the upper and mid-back to attach to the superior humerus. Positioned superficially to the ribs and intercostal muscles, it extends superiorly and laterally to the inferior scapula and humerus (see Image 1. Posterior Axioappendicular Muscles). Alongside the teres major and pectoralis major muscles, the latissimus dorsi contributes to arm adduction, medial rotation, and extension at the shoulder.[1]

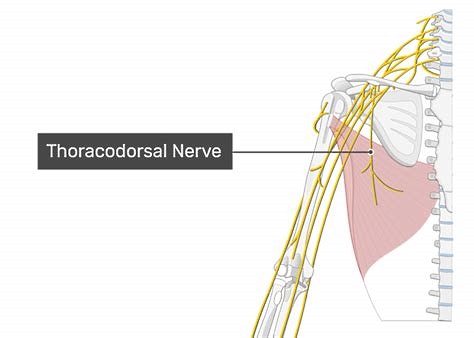

The latissimus dorsi is perfused by the thoracodorsal vessels and is innervated by the thoracodorsal nerve (see Image 2. The thoracodorsal artery, a terminal branch of the subscapular artery, descends along the lateral aspect of the back, typically accompanied by 1 or 2 venae comitantes. This artery gives off descending and transverse branches, with its terminal branches supplying the serratus anterior muscle. Blood vessels enter the latissimus dorsi muscle belly approximately 10 cm from its humeral insertion and continue along its deep surface.

Indications

Transferring the latissimus dorsi flap to reconstruct large defects in the head, neck, and chest regions is recommended. This flap is suitable for cases where extensive soft-tissue coverage is needed, especially in defects involving the entire scalp.[4]

Contraindications

An absolute contraindication for the latissimus dorsi flap arises when prior injuries or surgeries to the shoulder or back have disrupted the proposed flap's blood supply, rendering it compromised for transfer. Relative contraindications include smoking, diabetes, and poor vascular health. Smoking significantly impacts microcirculation, necessitating discussions about smoking cessation with patients. The risk of flap failure is higher in patients with diabetes, particularly those with poor glycemic control and compromised vascular health.

Moreover, when radiotherapy is planned after surgical resection and reconstruction for comprehensive cancer management, using a muscle-only flap with overlying split-thickness skin grafts becomes a relative contraindication. Notably, incorporating skin grafts necessitates a minimum 6-week healing interval before radiation exposure, potentially delaying the onset of radiotherapy.[9]

Equipment

The following equipment is necessary for a latissimus dorsi transfer:

- Surgical marker

- Bard-Parker scalpel handle (#15 blade on a #3)

- Doppler ultrasound probe

- Forceps, including DeBakey, Gerald, and Adson-Brown

- Hemostats

- Dissecting scissors, including Metzenbaum and Reynolds tenotomy

- Suture scissors, including Iris and Mayo

- Needle holders

- Bipolar and monopolar electrocautery

- Retractors, including Army-Navy, Richardson, and Senn

- Suction tips, including Goodhill and Frazier

- Gauze sponges

- Sutures for closure, including 3-0 or 4-0 nylon for the skin surface, 2-0 or 3-0 poliglecaprone for deep dermal closure, and 2-0 polyglactin for fascia

- Dermatome for split-thickness skin graft harvest (optional)

The following equipment is necessary for a free tissue transfer:

- Microvascular instruments, including needle holders, forceps, needle drivers, suture and adventitial scissors, vessel dilators, and vessel clamps

- Venous couplers

- Heparinized saline

- Weck cell spears

- Vessel loops

- Papaverine or 2% plain lidocaine

- Operating microscope

- Nylon sutures (8-0 or 9-0) on a tapered needle

Personnel

A latissimus dorsi flap transfer typically requires a minimum of 4 individuals in the operating room, including a surgeon, surgical technician, circulating nurse, and anesthesia personnel, as well as additional surgical assistants potentially needed for tissue retraction.

Preparation

Before undergoing a latissimus dorsi flap transfer, patients should undergo a thorough preoperative risk assessment to minimize potential complications. This assessment includes screening for cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions that may increase risks associated with general endotracheal anesthesia. While preoperative imaging of the harvest and inset sites is not mandatory for latissimus transfer, meticulous planning and preparation are crucial. Given the potential for significant blood loss during surgery, a type and screen should be conducted to prepare for the possibility of transfusion. Furthermore, assessing and optimizing patients' nutrition, electrolyte levels, thyroid hormone levels, and other wound-healing predictors is essential before reconstructive surgery.[8] These measures collectively contribute to enhancing patient safety and optimizing surgical outcomes.

Discussions with anesthesia personnel are crucial to ensure optimal perioperative management before latissimus dorsi flap transfer. Maintaining a mean arterial pressure of more than 60 mm Hg is advocated to ensure adequate flap perfusion, with considerations for the availability of crystalloid, colloid, and blood products.[10] When managing low blood pressure in patients, some advocate for colloid while others favor crystalloid or blood products. Concerned about the potential microcirculatory risks to the flap using vasopressors such as norepinephrine have been raised. However, existing literature supporting this perspective is limited, and outcomes in patients receiving vasopressors appear comparable to those who do not, given appropriate fluid management and avoidance of hypovolemia.[11][12][13] In instances where a vasopressor becomes necessary, dobutamine may offer benefits in terms of flap perfusion.[14]

Furthermore, maintaining the patient's and flap's temperature between 35 °C and 37 °C optimizes flap perfusion by preventing vasoconstriction, which requires coordination with the operating room and anesthesia personnel.[15] Finally, administering preoperative antibiotics and continuing them for several days postoperatively are essential to prevent infection and ensure optimal outcomes.

Technique or Treatment

Effective planning and execution of the latissimus dorsi flap procedure require carefully considering various techniques to ensure optimal outcomes in reconstructive surgery.

Positioning

While the conventional method involves harvesting the latissimus dorsi flap with the patient in a prone position and transitioning to a supine position for flap inset, alternative positions can also be effective. Some surgeons opt for a lateral decubitus or supine position with a padded bump or surgical assistant to maintain a slightly rotated orientation. These adaptations allow for successful flap harvesting while providing flexibility in positioning based on patient and surgeon preferences, potentially enhancing procedural efficiency and patient comfort. These variations offer flexibility and may suit specific patient needs or surgeon preferences. Adjusting the position for flap harvest and inset can enhance accessibility and comfort while upholding surgical precision and efficiency.

Measurement

Precise measurements ensure adequate tissue coverage and optimal outcomes when planning a pedicled flap. One effective method involves using a gauze strip to mark the distal edge of the flap, extending from the farthest edge of the wound to the pivot point, typically located between the scapula and axilla. Surgeons can accurately mark the flap's edge by anchoring 1 end of the gauze at the pivot point and rotating the other end to the back.

Similarly, determining the skin paddle harvest site is crucial for free tissue transfer based on the required pedicle length and location. Including the entrance point of the thoracodorsal artery into the latissimus muscle, typically around 10 cm beyond its attachment at the humeral head, is essential to ensure tissue viability and the success of the flap transfer. This meticulous planning is crucial in ensuring the viability and success of the flap transfer procedure.

Incisions

The surgical procedure begins with an incision along the midaxillary line, extending from the armpit downwards to the anterior-superior iliac spine. Deep dissection is then performed to locate the lateral edge of the latissimus muscle while carefully separating the serratus anterior and rhomboid muscles encountered during this process. The avascular plane beneath the latissimus dorsi is accessed, allowing visualization of the thoracodorsal vessels along the muscle's deep surface. Once the vessel location is confirmed, a medial incision outlines the skin paddle intended for harvesting, ensuring it directly overlies the blood vessels. Alternatively, if a skin paddle is not required, monopolar electrocautery is used to elevate the skin and subcutaneous tissue from the superficial muscle surface. This is followed by a medial incision through the muscle to include the thoracodorsal vessels.

In an alternative approach, the location of the flap skin paddle is determined based on the approximate entry point of the thoracodorsal vessels into the muscle. After marking, an incision is made in the skin, and dissection is carried down to the surface of the latissimus muscle. Electrocautery is used to expose the superficial surface of the muscle laterally and superiorly. Continuing the incision along the medial and inferior aspects of the skin paddle allows access to the deep surface of the latissimus muscle. The muscle is then bluntly elevated in a superolateral direction until visualization of the thoracodorsal vessels is achieved. The muscle surrounding the pedicle can be carefully narrowed to prevent vascular injury if necessary. During facial reanimation procedures, surgeons perform microsurgical coaptation of the thoracodorsal nerve, which runs parallel and lateral to the blood vessels, to the masseteric nerve. Alternatively, a cross-face nerve graft may be utilized.

Free Tissue Transfer

In free tissue transfer, the thoracodorsal vessels are dissected proximally to extend the pedicle length, necessitating ligation of the branches to the serratus anterior muscle and scapula. Once an adequate length is achieved, the pedicle can be ligated, and the flap is repositioned for microvascular anastomosis at its new site. In addition, it is crucial to minimize ischemia time (the duration between the division of the pedicle and the completion of microvascular anastomosis) to avoid irreversible muscle damage, which typically occurs after 3 hours.[16] If the anticipated ischemia time exceeds this limit, cooling and perfusion with heparinized saline may help protect the flap.[17]

Pedicled Flap Transfer

During pedicled flap transfer to the head and neck, it is crucial to detach the latissimus dorsi from the humeral head and ligate vessel branches to the scapula. This step facilitates flap rotation and prevents vessel kinking, which could compromise flap viability post-transfer. A subcutaneous plane superficial to the pectoralis muscle is developed for anterior torso transfer. In contrast, a similar tunnel is created superficial to the pectoralis muscle, the clavicle, and deep to the platysma for head and neck transfer. Additionally, an incision parallel and superior to the clavicle may aid in flap transfer in this region. Furthermore, creating wide tissue tunnels generously to accommodate the flap and prevent vascular compression in all pedicled flap transfer cases is essential.

Closure

After flap transfer, the latissimus is inset using layers of absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures. Achieving meticulous hemostasis at both the inset and donor sites is crucial to prevent hematoma development. In the case of a muscle-only flap transfer, it should be covered with split-thickness skin grafts and a bolster. Ideally, the donor site should be closed primarily; however, significant subcutaneous undermining may be necessary for advancement and closure, especially with large skin paddle transfers. If primary closure of the donor site is not feasible, the remaining open wound can be covered with split-thickness skin grafts and a bolster. After pedicled latissimus transfer, the patient is often placed in an arm sling to restrict shoulder and arm movement on the flap side during the initial healing phase.

Postprocedural Follow-up

Following free tissue transfer procedures, frequent flap examinations within the initial 48 to 72 hours are crucial to promptly identify any developing complications. Surgeons typically conduct hourly checks postoperatively during the first 24 hours, transitioning to checks every 2 hours for postoperative days 2 and 3. As reepithelialization progresses and the risk of venous thrombosis diminishes, examinations may become less frequent until discharge.[8]

During postprocedural checkups, clinicians assess color, warmth, turgor, capillary refill, and Doppler probe signals of the flap. Needle pricking is utilized to evaluate color and bleeding rapidity, aiding in the detection of venous congestion or arterial insufficiency. Ensuring meticulous intraoperative hemostasis and restricting postoperative activities for 2 weeks help reduce the risk of hematoma formation. In addition, maintaining controlled blood pressure is crucial to prevent vessel compression resulting from hematomas or wound infections.

Complications

The most concerning complication in flap surgery is flap failure, which can manifest as partial or complete loss due to vascular compromise during the initial few weeks of healing.[8] Prompt recognition and intervention are crucial for salvaging compromised flaps. Timely recognition of vascular compromise is essential, as early intervention can salvage flaps by addressing vascular occlusion and kinking or using leech therapy to mitigate venous congestion. Leeches aid in flap salvage by directly removing venous blood and secreting hirudin, which is a natural anticoagulant that inhibits thrombin from converting fibrinogen to fibrin and activating platelets.[18] However, when using leeches, the prophylactic administration of a fluoroquinolone antibiotic is crucial to prevent potential infection from Aeromonas hydrophila, commonly found in the gut of medicinal leeches.[19] Despite interventions, prolonged venous congestion or inadequate arterial inflow may lead to irreversible flap loss.

Early recognition of vascular insufficiency in a free latissimus dorsi flap is paramount, as irreversible microcirculatory damage can occur after 6 hours of ischemia.[20] A swift return to the operating room is crucial for restoring perfusion, with up to a 90% salvage rate achievable if corrective measures are promptly implemented.[21] Most vascular occlusions occur within the initial 48 hours, with later thromboses posing a lower salvage likelihood, particularly for muscle flaps.[21] To optimize circulation while preparing for urgent reoperation, interventions may include releasing sutures overlying the pedicle and administering aspirin and heparin. Another option is injecting a high-dose thrombolytic, such as streptokinase or urokinase, into the flap itself and draining it out of the flap vein rather than into the systemic circulation if direct mechanical thrombectomy fails.[22]

Clinical Significance

The latissimus dorsi flap, whether utilized as a free or pedicled transfer, with or without the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue, provides a straightforward yet versatile solution for reconstructive challenges involving the head, neck, and torso. The generous tissue coverage and favorable skin characteristics of the latissimus dorsi flap, such as color and texture, frequently result in aesthetically pleasing outcomes. Furthermore, its ability to manage extensive wounds where alternative options may be inadequate underscores its indispensable role in the reconstructive surgeon's repertoire.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective patient-centered care and optimal outcomes in latissimus dorsi flap procedures require a collaborative approach among interprofessional healthcare providers, including physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, and pharmacists. Surgeons must demonstrate proficiency in flap harvest and transfer techniques, as well as ensure meticulous dissection and hemostasis to prevent complications such as hematoma formation.

Interprofessional communication is crucial throughout the perioperative period, with anesthesiologists and surgical teams working together to maintain hemodynamic stability and optimal flap perfusion. Nurses are critical in preoperative patient education, postoperative monitoring, wound care, and pain management. Pharmacists ensure appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis and pain management regimens. Advanced practitioners facilitate comprehensive preoperative assessments and optimize patient health status before surgery. Through interdisciplinary collaboration and clear communication, healthcare teams can enhance patient safety, satisfaction, and outcomes in latissimus dorsi flap procedures.