[1]

Takeda E, Taketani Y, Sawada N, Sato T, Yamamoto H. The regulation and function of phosphate in the human body. BioFactors (Oxford, England). 2004:21(1-4):345-55

[PubMed PMID: 15630224]

[2]

Peacock M. Phosphate Metabolism in Health and Disease. Calcified tissue international. 2021 Jan:108(1):3-15. doi: 10.1007/s00223-020-00686-3. Epub 2020 Apr 7

[PubMed PMID: 32266417]

[3]

Bonora M,Patergnani S,Rimessi A,De Marchi E,Suski JM,Bononi A,Giorgi C,Marchi S,Missiroli S,Poletti F,Wieckowski MR,Pinton P, ATP synthesis and storage. Purinergic signalling. 2012 Sep;

[PubMed PMID: 22528680]

[4]

Amanzadeh J, Reilly RF Jr. Hypophosphatemia: an evidence-based approach to its clinical consequences and management. Nature clinical practice. Nephrology. 2006 Mar:2(3):136-48

[PubMed PMID: 16932412]

[5]

Koljonen L, Enlund-Cerullo M, Hauta-Alus H, Holmlund-Suila E, Valkama S, Rosendahl J, Andersson S, Pekkinen M, Mäkitie O. Phosphate Concentrations and Modifying Factors in Healthy Children From 12 to 24 Months of Age. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2021 Sep 27:106(10):2865-2875. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab495. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 34214153]

[6]

Haider DG, Lindner G, Wolzt M, Ahmad SS, Sauter T, Leichtle AB, Fiedler GM, Fuhrmann V, Exadaktylos AK. Hyperphosphatemia Is an Independent Risk Factor for Mortality in Critically Ill Patients: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study. PloS one. 2015:10(8):e0133426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133426. Epub 2015 Aug 7

[PubMed PMID: 26252874]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[7]

King AL, Sica DA, Miller G, Pierpaoli S. Severe hypophosphatemia in a general hospital population. Southern medical journal. 1987 Jul:80(7):831-5

[PubMed PMID: 3603104]

[8]

Berger MM, Appelberg O, Reintam-Blaser A, Ichai C, Joannes-Boyau O, Casaer M, Schaller SJ, Gunst J, Starkopf J, ESICM-MEN section. Prevalence of hypophosphatemia in the ICU - Results of an international one-day point prevalence survey. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2021 May:40(5):3615-3621. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.12.017. Epub 2020 Dec 29

[PubMed PMID: 33454128]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[9]

Wang L, Xiao C, Chen L, Zhang X, Kou Q. Impact of hypophosphatemia on outcome of patients in intensive care unit: a retrospective cohort study. BMC anesthesiology. 2019 May 24:19(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0746-2. Epub 2019 May 24

[PubMed PMID: 31122196]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[10]

Kim KJ, Song JE, Kim JH, Hong N, Kim SG, Lee J, Rhee Y. Elevated morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic idiopathic hypophosphatemia: a nationwide cohort study. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2023:14():1229750. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1229750. Epub 2023 Aug 10

[PubMed PMID: 37635983]

[11]

Uribarri J, Calvo MS. Hidden sources of phosphorus in the typical American diet: does it matter in nephrology? Seminars in dialysis. 2003 May-Jun:16(3):186-8

[PubMed PMID: 12753675]

[12]

Peacock M. Calcium metabolism in health and disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2010 Jan:5 Suppl 1():S23-30. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05910809. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20089499]

[13]

Stremke ER, Hill Gallant KM. Intestinal Phosphorus Absorption in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients. 2018 Sep 23:10(10):. doi: 10.3390/nu10101364. Epub 2018 Sep 23

[PubMed PMID: 30249044]

[14]

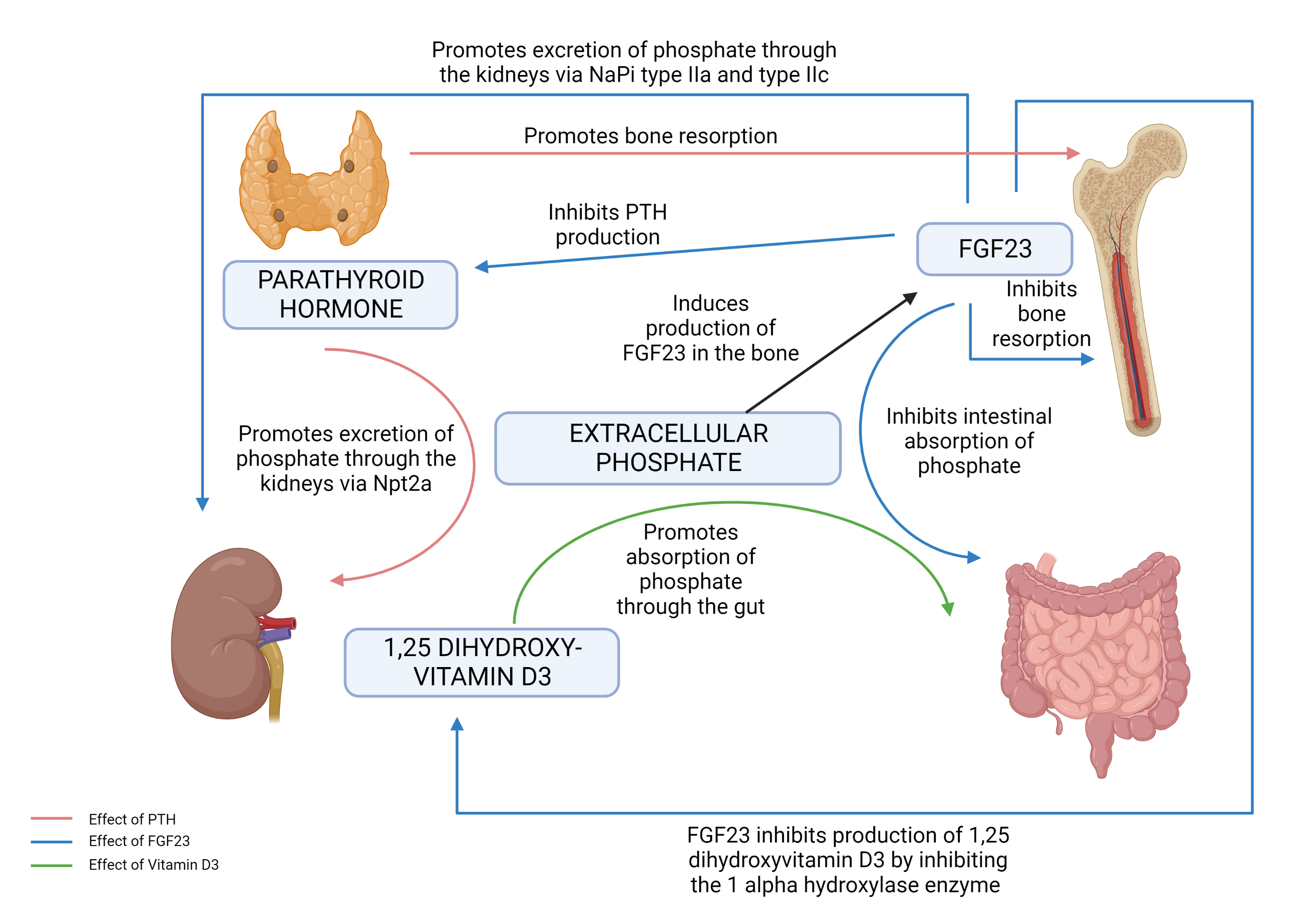

Berndt T, Kumar R. Novel mechanisms in the regulation of phosphorus homeostasis. Physiology (Bethesda, Md.). 2009 Feb:24():17-25. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00034.2008. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19196648]

[15]

Blaine J, Chonchol M, Levi M. Renal control of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium homeostasis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2015 Jul 7:10(7):1257-72. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09750913. Epub 2014 Oct 6

[PubMed PMID: 25287933]

[16]

Segawa H, Shiozaki Y, Kaneko I, Miyamoto K. The Role of Sodium-Dependent Phosphate Transporter in Phosphate Homeostasis. Journal of nutritional science and vitaminology. 2015:61 Suppl():S119-21. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.61.S119. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26598821]

[17]

Lederer E. Regulation of serum phosphate. The Journal of physiology. 2014 Sep 15:592(18):3985-95. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273979. Epub 2014 Jun 27

[PubMed PMID: 24973411]

[18]

Huang X, Jiang Y, Xia W. FGF23 and Phosphate Wasting Disorders. Bone research. 2013 Jun:1(2):120-32. doi: 10.4248/BR201302002. Epub 2013 Jun 28

[PubMed PMID: 26273497]

[19]

Liamis G, Milionis HJ, Elisaf M. Medication-induced hypophosphatemia: a review. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2010 Jul:103(7):449-59. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq039. Epub 2010 Mar 30

[PubMed PMID: 20356849]

[20]

Kaur U, Chakrabarti SS, Gambhir IS. Zoledronate Induced Hypocalcemia and Hypophosphatemia in Osteoporosis: A Cause of Concern. Current drug safety. 2016:11(3):267-9

[PubMed PMID: 27113952]

[21]

Clark SL, Nystrom EM. A Case of Severe, Prolonged, Refractory Hypophosphatemia After Zoledronic Acid Administration. Journal of pharmacy practice. 2016 Apr:29(2):172-6. doi: 10.1177/0897190015624050. Epub 2016 Jan 5

[PubMed PMID: 26739479]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[22]

Nowack R, Wachtler P. Hypophosphatemia and hungry bone syndrome in a dialysis patient with secondary hyperparathyroidism treated with cinacalcet--proposal for an improved monitoring. Clinical laboratory. 2006:52(11-12):583-7

[PubMed PMID: 17175888]

[23]

Kalantar-Zadeh K, Ganz T, Trumbo H, Seid MH, Goodnough LT, Levine MA. Parenteral iron therapy and phosphorus homeostasis: A review. American journal of hematology. 2021 May 1:96(5):606-616. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26100. Epub 2021 Feb 9

[PubMed PMID: 33471363]

[24]

van der Vaart A, Waanders F, van Beek AP, Vriesendorp TM, Wolffenbutel BHR, van Dijk PR. Incidence and determinants of hypophosphatemia in diabetic ketoacidosis: an observational study. BMJ open diabetes research & care. 2021 Feb:9(1):. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-002018. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 33597187]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[25]

Barak V, Schwartz A, Kalickman I, Nisman B, Gurman G, Shoenfeld Y. Prevalence of hypophosphatemia in sepsis and infection: the role of cytokines. The American journal of medicine. 1998 Jan:104(1):40-7

[PubMed PMID: 9528718]

[26]

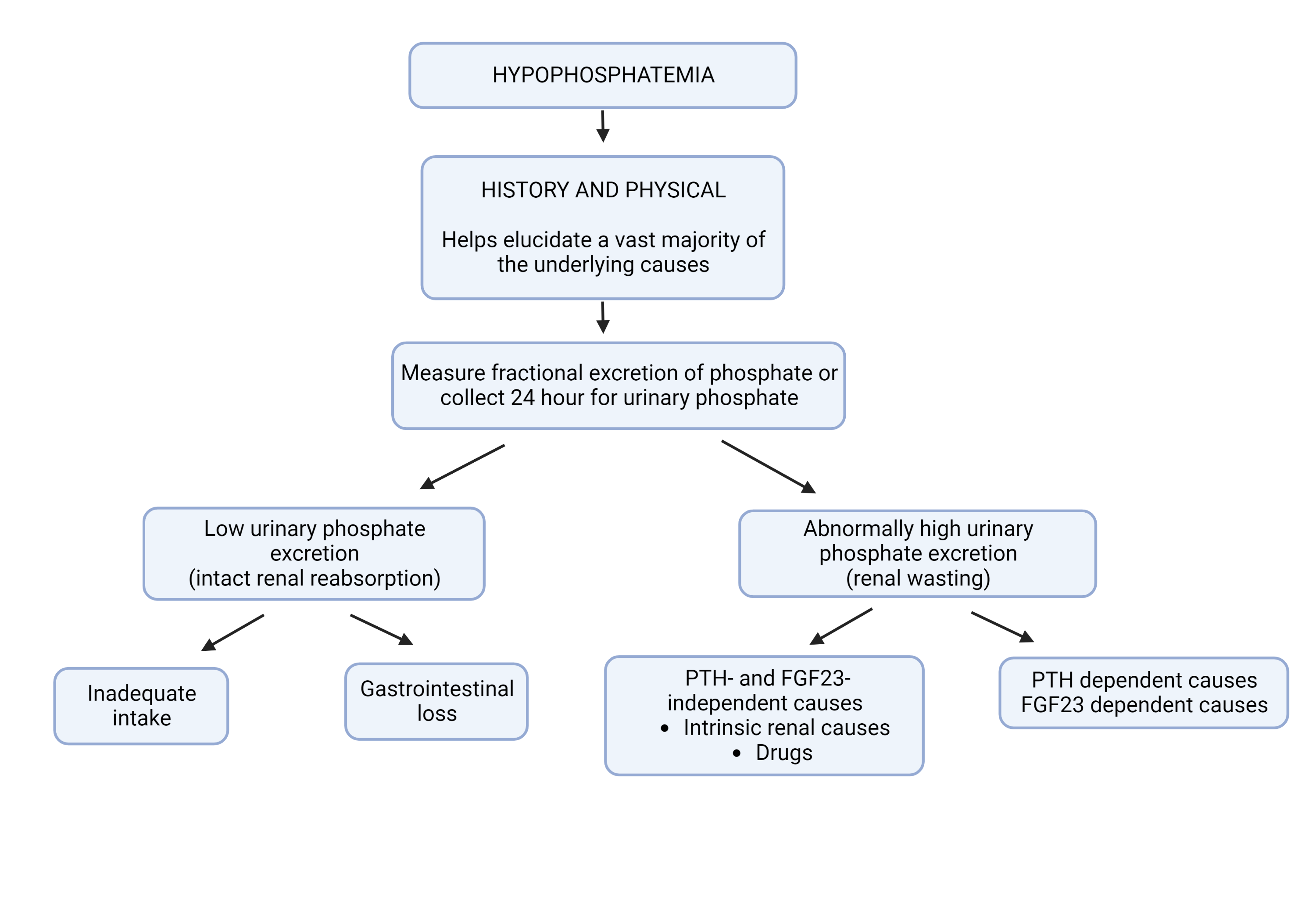

Gaasbeek A, Meinders AE. Hypophosphatemia: an update on its etiology and treatment. The American journal of medicine. 2005 Oct:118(10):1094-101

[PubMed PMID: 16194637]

[27]

Camp MA,Allon M, Severe hypophosphatemia in hospitalized patients. Mineral and electrolyte metabolism. 1990;

[PubMed PMID: 2089250]

[28]

Uday S, Sakka S, Davies JH, Randell T, Arya V, Brain C, Tighe M, Allgrove J, Arundel P, Pryce R, Högler W, Shaw NJ. Elemental formula associated hypophosphataemic rickets. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2019 Oct:38(5):2246-2250. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.09.028. Epub 2018 Sep 28

[PubMed PMID: 30314926]

[29]

Christov M, Jüppner H. Phosphate homeostasis disorders. Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2018 Oct:32(5):685-706. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2018.06.004. Epub 2018 Jun 18

[PubMed PMID: 30449549]

[30]

Jacquillet G, Unwin RJ. Physiological regulation of phosphate by vitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and phosphate (Pi). Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2019 Jan:471(1):83-98. doi: 10.1007/s00424-018-2231-z. Epub 2018 Nov 5

[PubMed PMID: 30393837]

[31]

Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutiérrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, Appleby D, Nessel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Hamm L, Gadegbeku C, Horwitz E, Townsend RR, Anderson CA, Lash JP, Hsu CY, Leonard MB, Wolf M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2011 Jun:79(12):1370-8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.47. Epub 2011 Mar 9

[PubMed PMID: 21389978]

[32]

Kurpas A, Supeł K, Idzikowska K, Zielińska M. FGF23: A Review of Its Role in Mineral Metabolism and Renal and Cardiovascular Disease. Disease markers. 2021:2021():8821292. doi: 10.1155/2021/8821292. Epub 2021 May 17

[PubMed PMID: 34055103]

[33]

Gutiérrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, Smith K, Lee H, Thadhani R, Jüppner H, Wolf M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. The New England journal of medicine. 2008 Aug 7:359(6):584-92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18687639]

[34]

Prasad N, Bhadauria D. Renal phosphate handling: Physiology. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2013 Jul:17(4):620-7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.113752. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23961477]

[35]

Lederer E, Miyamoto K. Clinical consequences of mutations in sodium phosphate cotransporters. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2012 Jul:7(7):1179-87. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09090911. Epub 2012 Apr 19

[PubMed PMID: 22516291]

[36]

King AJ, Siegel M, He Y, Nie B, Wang J, Koo-McCoy S, Minassian NA, Jafri Q, Pan D, Kohler J, Kumaraswamy P, Kozuka K, Lewis JG, Dragoli D, Rosenbaum DP, O'Neill D, Plain A, Greasley PJ, Jönsson-Rylander AC, Karlsson D, Behrendt M, Strömstedt M, Ryden-Bergsten T, Knöpfel T, Pastor Arroyo EM, Hernando N, Marks J, Donowitz M, Wagner CA, Alexander RT, Caldwell JS. Inhibition of sodium/hydrogen exchanger 3 in the gastrointestinal tract by tenapanor reduces paracellular phosphate permeability. Science translational medicine. 2018 Aug 29:10(456):. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam6474. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30158152]

[37]

Ansermet C, Moor MB, Centeno G, Auberson M, Hu DZ, Baron R, Nikolaeva S, Haenzi B, Katanaeva N, Gautschi I, Katanaev V, Rotman S, Koesters R, Schild L, Pradervand S, Bonny O, Firsov D. Renal Fanconi Syndrome and Hypophosphatemic Rickets in the Absence of Xenotropic and Polytropic Retroviral Receptor in the Nephron. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2017 Apr:28(4):1073-1078. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016070726. Epub 2016 Oct 31

[PubMed PMID: 27799484]

[38]

Mandry JM, Posner MR, Tucci JR, Eil C. Hyperphosphatemia in multiple myeloma due to a phosphate-binding immunoglobulin. Cancer. 1991 Sep 1:68(5):1092-4

[PubMed PMID: 1913479]

[39]

Goyal JP, Kumar N, Rao SS, Shah VB. Wilson's Disease Presenting as Resistant Rickets. Gastroenterology research. 2011 Feb:4(1):34-35

[PubMed PMID: 27957011]

[40]

Subrahmanyam DK, Vadivelan M, Giridharan S, Balamurugan N. Wilson's disease - A rare cause of renal tubular acidosis with metabolic bone disease. Indian journal of nephrology. 2014 May:24(3):171-4. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.132017. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25120295]

[41]

Déliot N, Hernando N, Horst-Liu Z, Gisler SM, Capuano P, Wagner CA, Bacic D, O'Brien S, Biber J, Murer H. Parathyroid hormone treatment induces dissociation of type IIa Na+-P(i) cotransporter-Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor-1 complexes. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2005 Jul:289(1):C159-67

[PubMed PMID: 15788483]

[42]

Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2008 Jun 28:336(7659):1495-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a301. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18583681]

[43]

Witteveen JE, van Thiel S, Romijn JA, Hamdy NA. Hungry bone syndrome: still a challenge in the post-operative management of primary hyperparathyroidism: a systematic review of the literature. European journal of endocrinology. 2013 Mar:168(3):R45-53. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0528. Epub 2013 Feb 20

[PubMed PMID: 23152439]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[44]

Hoppe A, Metler M, Berndt TJ, Knox FG, Angielski S. Effect of respiratory alkalosis on renal phosphate excretion. The American journal of physiology. 1982 Nov:243(5):F471-5

[PubMed PMID: 6291407]

[45]

Paleologos M, Stone E, Braude S. Persistent, progressive hypophosphataemia after voluntary hyperventilation. Clinical science (London, England : 1979). 2000 May:98(5):619-25

[PubMed PMID: 10781395]

[46]

Tejeda A, Saffarian N, Uday K, Dave M. Hypophosphatemia in end stage renal disease. Nephron. 1996:73(4):674-8

[PubMed PMID: 8856268]

[47]

Hendrix RJ, Hastings MC, Samarin M, Hudson JQ. Predictors of Hypophosphatemia and Outcomes during Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Blood purification. 2020:49(6):700-707. doi: 10.1159/000507421. Epub 2020 Apr 22

[PubMed PMID: 32320987]

[48]

Torregrosa JV, Ferreira AC, Cucchiari D, Ferreira A. Bone Mineral Disease After Kidney Transplantation. Calcified tissue international. 2021 Apr:108(4):551-560. doi: 10.1007/s00223-021-00837-0. Epub 2021 Mar 25

[PubMed PMID: 33765230]

[49]

Halevy J, Bulvik S. Severe hypophosphatemia in hospitalized patients. Archives of internal medicine. 1988 Jan:148(1):153-5

[PubMed PMID: 3122679]

[50]

Lentz RD, Brown DM, Kjellstrand CM. Treatment of severe hypophosphatemia. Annals of internal medicine. 1978 Dec:89(6):941-4

[PubMed PMID: 102230]

[51]

Felsenfeld AJ, Levine BS. Approach to treatment of hypophosphatemia. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2012 Oct:60(4):655-61. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.024. Epub 2012 Aug 3

[PubMed PMID: 22863286]

[52]

Al Harbi SA, Al-Dorzi HM, Al Meshari AM, Tamim H, Abdukahil SAI, Sadat M, Arabi Y. Association between phosphate disturbances and mortality among critically ill patients with sepsis or septic shock. BMC pharmacology & toxicology. 2021 May 28:22(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s40360-021-00487-w. Epub 2021 May 28

[PubMed PMID: 34049590]

[53]

Shor R, Halabe A, Rishver S, Tilis Y, Matas Z, Fux A, Boaz M, Weinstein J. Severe hypophosphatemia in sepsis as a mortality predictor. Annals of clinical and laboratory science. 2006 Winter:36(1):67-72

[PubMed PMID: 16501239]

[54]

Miller CJ, Doepker BA, Springer AN, Exline MC, Phillips G, Murphy CV. Impact of Serum Phosphate in Mechanically Ventilated Patients With Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2020 May:35(5):485-493. doi: 10.1177/0885066618762753. Epub 2018 Mar 8

[PubMed PMID: 29519205]

[55]

Prié D, Huart V, Bakouh N, Planelles G, Dellis O, Gérard B, Hulin P, Benqué-Blanchet F, Silve C, Grandchamp B, Friedlander G. Nephrolithiasis and osteoporosis associated with hypophosphatemia caused by mutations in the type 2a sodium-phosphate cotransporter. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Sep 26:347(13):983-91

[PubMed PMID: 12324554]

[56]

Funabiki Y, Tatsukawa H, Ashida K, Matsubara K, Kubota Y, Uwatoko H, Kitamura K. Disturbance of consciousness associated with hypophosphatemia in a chronically alcoholic patient. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 1998 Nov:37(11):958-61

[PubMed PMID: 9868960]

[57]

Singhal PC, Kumar A, Desroches L, Gibbons N, Mattana J. Prevalence and predictors of rhabdomyolysis in patients with hypophosphatemia. The American journal of medicine. 1992 May:92(5):458-64

[PubMed PMID: 1580292]

[58]

Junge O. [Acute polyneuropathy due to phosphate deficiency during parenteral feeding]. Fortschritte der Medizin. 1979 Feb 22:97(8):335-8

[PubMed PMID: 105978]

[59]

Imel EA, Econs MJ. Approach to the hypophosphatemic patient. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2012 Mar:97(3):696-706. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1319. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22392950]

[60]

Fuller TJ, Nichols WW, Brenner BJ, Peterson JC. Reversible depression in myocardial performance in dogs with experimental phosphorus deficiency. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1978 Dec:62(6):1194-1200

[PubMed PMID: 748374]

[61]

Davis SV, Olichwier KK, Chakko SC. Reversible depression of myocardial performance in hypophosphatemia. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1988 Mar:295(3):183-7

[PubMed PMID: 3354591]

[62]

Gravelyn TR, Brophy N, Siegert C, Peters-Golden M. Hypophosphatemia-associated respiratory muscle weakness in a general inpatient population. The American journal of medicine. 1988 May:84(5):870-6

[PubMed PMID: 3364446]

[63]

Zhao Y, Li Z, Shi Y, Cao G, Meng F, Zhu W, Yang GE. Effect of hypophosphatemia on the withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biomedical reports. 2016 Apr:4(4):413-416

[PubMed PMID: 27073623]

[64]

Alsumrain MH, Jawad SA, Imran NB, Riar S, DeBari VA, Adelman M. Association of hypophosphatemia with failure-to-wean from mechanical ventilation. Annals of clinical and laboratory science. 2010 Spring:40(2):144-8

[PubMed PMID: 20421625]

[65]

Altuntas Y, Innice M, Basturk T, Seber S, Serin G, Ozturk B. Rhabdomyolysis and severe haemolytic anaemia, hepatic dysfunction and intestinal osteopathy due to hypophosphataemia in a patient after Billroth II gastrectomy. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2002 May:14(5):555-7

[PubMed PMID: 11984155]

[66]

Melvin JD, Watts RG. Severe hypophosphatemia: a rare cause of intravascular hemolysis. American journal of hematology. 2002 Mar:69(3):223-4

[PubMed PMID: 11891812]