[1]

Fernández-Cañón JM,Granadino B,Beltrán-Valero de Bernabé D,Renedo M,Fernández-Ruiz E,Peñalva MA,Rodríguez de Córdoba S, The molecular basis of alkaptonuria. Nature genetics. 1996 Sep;

[PubMed PMID: 8782815]

[3]

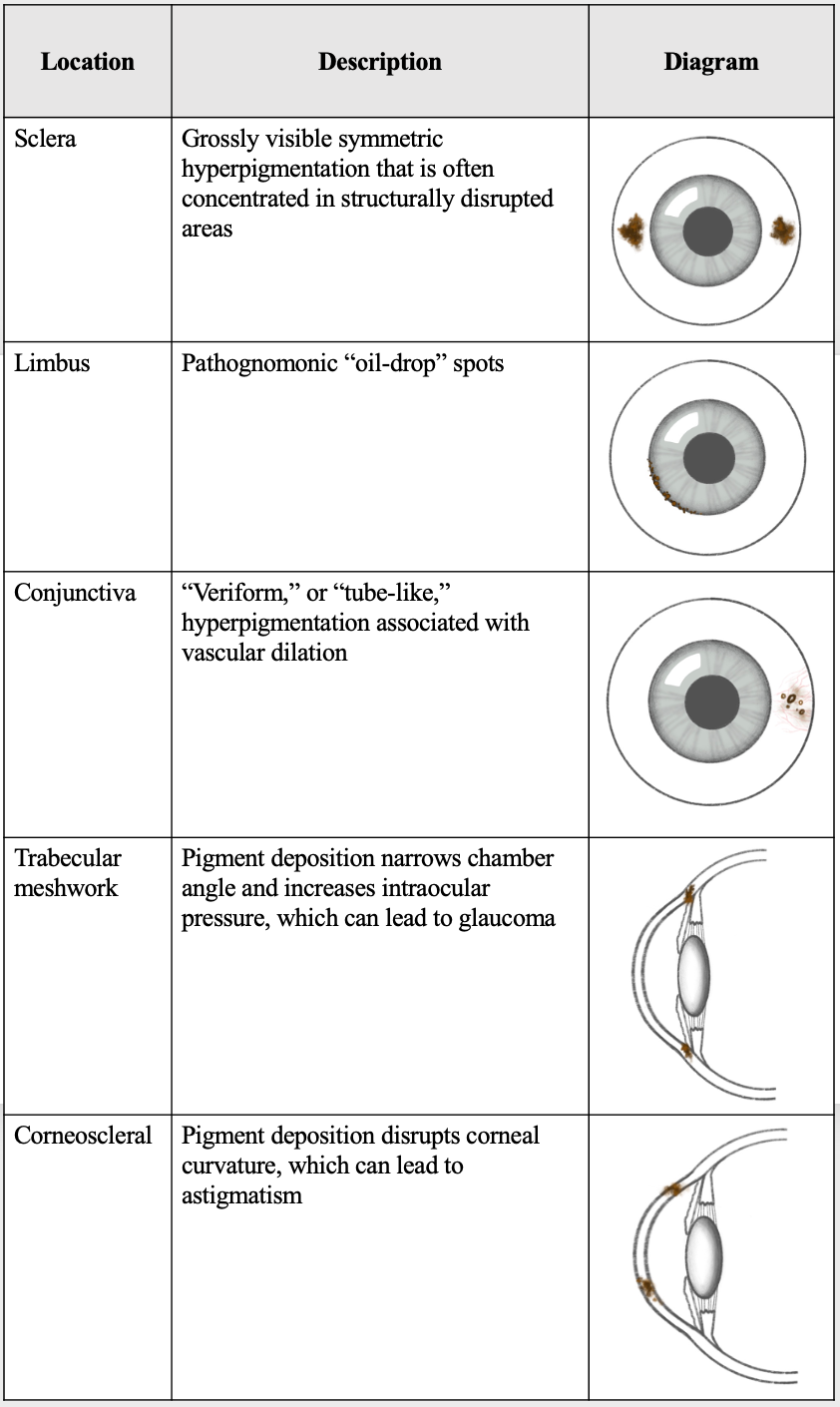

Lindner M,Bertelmann T, On the ocular findings in ochronosis: a systematic review of literature. BMC ophthalmology. 2014 Jan 30;

[PubMed PMID: 24479547]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[4]

Stenn FF,Milgram JW,Lee SL,Weigand RJ,Veis A, Biochemical identification of homogentisic acid pigment in an ochronotic egyptian mummy. Science (New York, N.Y.). 1977 Aug 5;

[PubMed PMID: 327549]

[5]

Garrod AE, The incidence of alkaptonuria: a study in chemical individuality. 1902. Molecular medicine (Cambridge, Mass.). 1996 May;

[PubMed PMID: 8784780]

[6]

Scriver CR, Garrod's Croonian Lectures (1908) and the charter 'Inborn Errors of Metabolism': albinism, alkaptonuria, cystinuria, and pentosuria at age 100 in 2008. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2008 Oct;

[PubMed PMID: 18850300]

[7]

LA DU BN,ZANNONI VG,LASTER L,SEEGMILLER JE, The nature of the defect in tyrosine metabolism in alcaptonuria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1958 Jan;

[PubMed PMID: 13502394]

[8]

Janocha S,Wolz W,Srsen S,Srsnova K,Montagutelli X,Guénet JL,Grimm T,Kress W,Müller CR, The human gene for alkaptonuria (AKU) maps to chromosome 3q. Genomics. 1994 Jan 1;

[PubMed PMID: 8188241]

[9]

Zatkova A, An update on molecular genetics of Alkaptonuria (AKU). Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2011 Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 21720873]

[10]

Jónsson H,Sulem P,Kehr B,Kristmundsdottir S,Zink F,Hjartarson E,Hardarson MT,Hjorleifsson KE,Eggertsson HP,Gudjonsson SA,Ward LD,Arnadottir GA,Helgason EA,Helgason H,Gylfason A,Jonasdottir A,Jonasdottir A,Rafnar T,Frigge M,Stacey SN,Th Magnusson O,Thorsteinsdottir U,Masson G,Kong A,Halldorsson BV,Helgason A,Gudbjartsson DF,Stefansson K, Parental influence on human germline de novo mutations in 1,548 trios from Iceland. Nature. 2017 Sep 28;

[PubMed PMID: 28959963]

[11]

Goicoechea De Jorge E,Lorda I,Gallardo ME,Pérez B,Peréz De Ferrán C,Mendoza H,Rodríguez De Córdoba S, Alkaptonuria in the Dominican Republic: identification of the founder AKU mutation and further evidence of mutation hot spots in the HGO gene. Journal of medical genetics. 2002 Jul;

[PubMed PMID: 12114497]

[12]

Khalil R,Ali D,Mwafi N,Alsaraireh A,Obeidat L,Albsoul E,Al Sbou' I, Variant Analysis of Alkaptonuria Families with Significant Founder Effect in Jordan. BioMed research international. 2021;

[PubMed PMID: 34235214]

[13]

Phornphutkul C,Introne WJ,Perry MB,Bernardini I,Murphey MD,Fitzpatrick DL,Anderson PD,Huizing M,Anikster Y,Gerber LH,Gahl WA, Natural history of alkaptonuria. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Dec 26;

[PubMed PMID: 12501223]

[14]

Jiang L,Cao L,Fang J,Yu X,Dai X,Miao X, Ochronotic arthritis and ochronotic Achilles tendon rupture in alkaptonuria: A 6 years follow-up case report in China. Medicine. 2019 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 31441856]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[17]

Kisa PT,Gunduz M,Dorum S,Uzun OU,Cakar NE,Yildirim GK,Erdol S,Hismi BO,Tugsal HY,Ucar U,Gorukmez O,Gulten ZA,Kucukcongar A,Bulbul S,Sari I,Arslan N, Alkaptonuria in Turkey: Clinical and molecular characteristics of 66 patients. European journal of medical genetics. 2021 May;

[PubMed PMID: 33746036]

[18]

Kampik A,Sani JN,Green WR, Ocular ochronosis. Clinicopathological, histochemical, and ultrastructural studies. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1980 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 7417082]

[19]

Chévez Barrios P,Font RL, Pigmented conjunctival lesions as initial manifestation of ochronosis. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2004 Jul;

[PubMed PMID: 15249376]

[21]

Ben Rayana N,Chahed N,Khochtali S,Ghorbel M,Hamdi R,Rouis M,Bouajina I,Hamida FB, [Ocular ochronosis. A case report]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2008 Jun;

[PubMed PMID: 18772817]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[22]

Bacchetti S,Zeppieri M,Brusini P, A case of ocular ochronosis and chronic open-angle glaucoma: merely coincidental? Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2004 Oct;

[PubMed PMID: 15453872]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[23]

Ehongo A,Schrooyen M,Pereleux A, [Important bilateral corneal astigmatism in a case of ocular ochronosis]. Bulletin de la Societe belge d'ophtalmologie. 2005;

[PubMed PMID: 15849984]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[24]

John SS,Padhan P,Mathews JV,David S, Acute anterior uveitis as the initial presentation of alkaptonuria. Journal of postgraduate medicine. 2009 Jan-Mar;

[PubMed PMID: 19242077]

[25]

ASHTON N,KIRKER JG,LAVERY FS, OCULAR FINDINGS IN A CASE OF HEREDITARY OCHRONOSIS. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1964 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 14205517]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[26]

Damarla N,Linga P,Goyal M,Tadisina SR,Reddy GS,Bommisetti H, Alkaptonuria: A case report. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Jun;

[PubMed PMID: 28643719]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[27]

Pandey R,Kumar A,Garg R,Khanna P,Darlong V, Perioperative management of patient with alkaptonuria and associated multiple comorbidities. Journal of anaesthesiology, clinical pharmacology. 2011 Apr

[PubMed PMID: 21772695]

[29]

Introne WJ,Perry MB,Troendle J,Tsilou E,Kayser MA,Suwannarat P,O'Brien KE,Bryant J,Sachdev V,Reynolds JC,Moylan E,Bernardini I,Gahl WA, A 3-year randomized therapeutic trial of nitisinone in alkaptonuria. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2011 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 21620748]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[30]

Suwannarat P,O'Brien K,Perry MB,Sebring N,Bernardini I,Kaiser-Kupfer MI,Rubin BI,Tsilou E,Gerber LH,Gahl WA, Use of nitisinone in patients with alkaptonuria. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2005 Jun;

[PubMed PMID: 15931605]

[31]

de Haas V,Carbasius Weber EC,de Klerk JB,Bakker HD,Smit GP,Huijbers WA,Duran M,Poll-The BT, The success of dietary protein restriction in alkaptonuria patients is age-dependent. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 1998 Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 9870204]

[32]

Morava E,Kosztolányi G,Engelke UF,Wevers RA, Reversal of clinical symptoms and radiographic abnormalities with protein restriction and ascorbic acid in alkaptonuria. Annals of clinical biochemistry. 2003 Jan;

[PubMed PMID: 12542920]

[33]

Kamoun P,Coude M,Forest M,Montagutelli X,Guenet JL, Ascorbic acid and alkaptonuria. European journal of pediatrics. 1992 Feb;

[PubMed PMID: 1537362]

[34]

Wolff JA,Barshop B,Nyhan WL,Leslie J,Seegmiller JE,Gruber H,Garst M,Winter S,Michals K,Matalon R, Effects of ascorbic acid in alkaptonuria: alterations in benzoquinone acetic acid and an ontogenic effect in infancy. Pediatric research. 1989 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 2771520]

[35]

SKINSNES OK, Generalized ochronosis; report of an instance in which it was misdiagnosed as melanosarcoma, with resultant enucleation of an eye. Archives of pathology. 1948 Apr;

[PubMed PMID: 18891026]

[36]

Ranganath LR,Psarelli EE,Arnoux JB,Braconi D,Briggs M,Bröijersén A,Loftus N,Bygott H,Cox TF,Davison AS,Dillon JP,Fisher M,FitzGerald R,Genovese F,Glasova H,Hall AK,Hughes AT,Hughes JH,Imrich R,Jarvis JC,Khedr M,Laan D,Le Quan Sang KH,Luangrath E,Lukáčová O,Milan AM,Mistry A,Mlynáriková V,Norman BP,Olsson B,Rhodes NP,Rovenský J,Rudebeck M,Santucci A,Shweihdi E,Scott C,Sedláková J,Sireau N,Stančík R,Szamosi J,Taylor S,van Kan C,Vinjamuri S,Vrtíková E,Webb C,West E,Záňová E,Zatkova A,Gallagher JA, Efficacy and safety of once-daily nitisinone for patients with alkaptonuria (SONIA 2): an international, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The lancet. Diabetes

[PubMed PMID: 32822600]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence