[1]

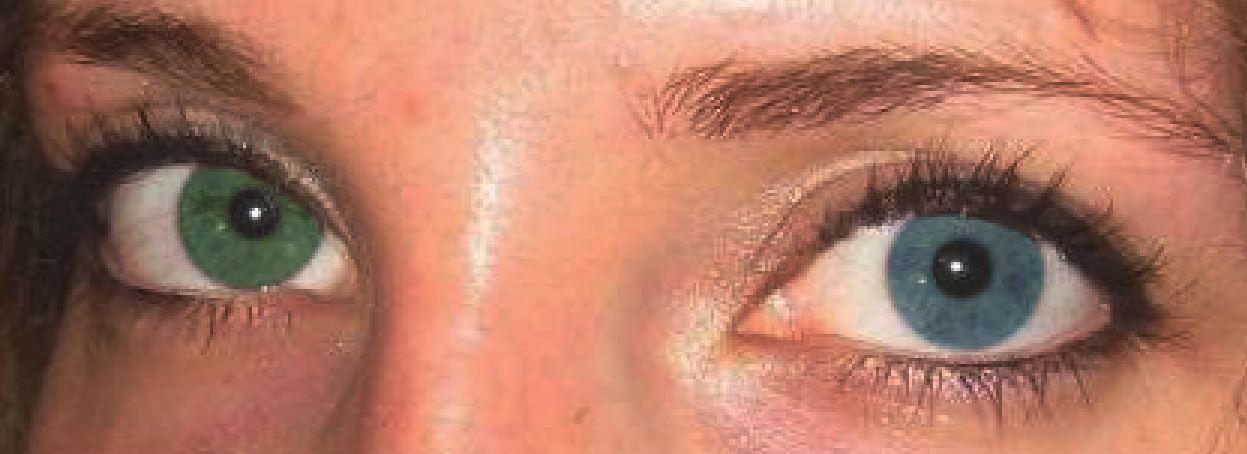

Ur Rehman H, Heterochromia. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2008 Aug 26;

[PubMed PMID: 18725617]

[2]

Prota G,Hu DN,Vincensi MR,McCormick SA,Napolitano A, Characterization of melanins in human irides and cultured uveal melanocytes from eyes of different colors. Experimental eye research. 1998 Sep

[PubMed PMID: 9778410]

[3]

Imesch PD,Wallow IH,Albert DM, The color of the human eye: a review of morphologic correlates and of some conditions that affect iridial pigmentation. Survey of ophthalmology. 1997 Feb

[PubMed PMID: 9154287]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[4]

Tomar M,Dhiman R,Sharma G,Yadav N, Artistic Iris: A Case of Congenital Sectoral Heterochromia Iridis. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2018 Jul-Sep

[PubMed PMID: 30090196]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[5]

Renard D,Jeanjean L,Labauge P, Heterochromia Iridis in congenital Horner's syndrome. European neurology. 2010;

[PubMed PMID: 20375515]

[6]

Diagne JP,Sow AS,Ka AM,Wane AM,Ndoye Roth PA,Ba EA,De Medeiros ME,Ndiaye JM,Diallo HM,Kane H,Sow S,Nguer M,Sy EM,Ndiaye PA, [Rare causes of childhood leukocoria]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2017 Oct

[PubMed PMID: 28893456]

[7]

Deprez FC,Coulier J,Rommel D,Boschi A, Congenital horner syndrome with heterochromia iridis associated with ipsilateral internal carotid artery hypoplasia. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea). 2015 Apr;

[PubMed PMID: 25749818]

[8]

Liu Y,Pan H,Wang J,Yao Q,Lin M,Ma B,Li J, Ophthalmological features and treatments in five cases of Waardenburg syndrome. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2020 Oct;

[PubMed PMID: 32855674]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[9]

Arif T,Fatima R,Sami M, Parry-Romberg syndrome: a mini review. Acta dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica, et Adriatica. 2020 Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 33348939]

[10]

Hassanpour K,Nourinia R,Gerami E,Mahmoudi G,Esfandiari H, Ocular Manifestations of the Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Journal of ophthalmic

[PubMed PMID: 34394871]

[11]

Pinti E,Nemeth K,Staub K,Lengyel A,Fekete G,Haltrich I, Diagnostic difficulties and possibilities of NF1-like syndromes in childhood. BMC pediatrics. 2021 Jul 29;

[PubMed PMID: 34325699]

[12]

Sarker BK,Malek MA,Abdullahi S,Iftekhar S,Sakeb N,Mahatma M,Sarkar MK, Ophthalmic associations of oculodermal melanocytosis in a tertiary eye hospital in South Asia. Therapeutic advances in ophthalmology. 2021 Jan-Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 33644684]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[13]

Chaurasia S,Choudhari NS,Mohamed A, Clinical and Specular microscopy characteristics and corelation in Iridocorneal endothelial syndrome without corneal edema. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2021 Oct 3

[PubMed PMID: 33750265]

[15]

Wallis DH,Granet DB,Levi L, When the darker eye has the smaller pupil. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2003 Jun;

[PubMed PMID: 12825064]

[16]

Pérez-Torres-Lobato MR,De Las Morenas-Iglesias J,Llempén-López M,Gómez-Millán-Ruiz P,Márquez-Vega C,Espiñeira-Periñán MÁ,Coronel-Rodríguez C,Franco-Ruedas C,Balboa-Huguet B,Sánchez-Vicente JL, Paediatric Horner syndrome. A case series of 14 patients in a tertiary hospital. Archivos de la Sociedad Espanola de Oftalmologia. 2021 Jul;

[PubMed PMID: 34217473]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[18]

Stjernschantz JW,Albert DM,Hu DN,Drago F,Wistrand PJ, Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Survey of ophthalmology. 2002 Aug;

[PubMed PMID: 12204714]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[19]

Doyle E,Liu C, A case of acquired iris depigmentation as a possible complication of levobunolol eye drops. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1999 Dec

[PubMed PMID: 10660314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[20]

Mehta K,Haller JO,Legasto AC, Imaging neuroblastoma in children. Critical reviews in computed tomography. 2003;

[PubMed PMID: 12627783]

[21]

Abramson SJ,Berdon WE,Ruzal-Shapiro C,Stolar C,Garvin J, Cervical neuroblastoma in eleven infants--a tumor with favorable prognosis. Clinical and radiologic (US, CT, MRI) findings. Pediatric radiology. 1993

[PubMed PMID: 8414748]

[22]

Irwin MS,Naranjo A,Zhang FF,Cohn SL,London WB,Gastier-Foster JM,Ramirez NC,Pfau R,Reshmi S,Wagner E,Nuchtern J,Asgharzadeh S,Shimada H,Maris JM,Bagatell R,Park JR,Hogarty MD, Revised Neuroblastoma Risk Classification System: A Report From the Children's Oncology Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2021 Jul 28;

[PubMed PMID: 34319759]

[23]

Grant CN,Rhee D,Tracy ET,Aldrink JH,Baertschiger RM,Lautz TB,Glick RD,Rodeberg DA,Ehrlich PF,Christison-Lagay E, Pediatric solid tumors and associated cancer predisposition syndromes: Workup, management, and surveillance. A summary from the APSA cancer committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2021 Aug 24

[PubMed PMID: 34503817]