Continuing Education Activity

Lacrimal gland masses can have many etiologies, including neoplastic and non-neoplastic causes. Of the neoplastic causes, benign etiologies are more common than malignant. However, since they are still rare, they can present a diagnostic challenge. The following reviews the evaluation and treatment of benign lacrimal gland tumors and explains the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with these conditions.

Objectives:

- Describe the presentation and appropriate clinical evaluation for a patient with a suspected lacrimal gland mass.

- Review the benign causes of lacrimal gland tumors.

- Identify factors of the patient history, physical examination, and imaging modalities that guide management and treatment.

- Summarize the treatment options for the various benign lacrimal gland lesions.

Introduction

Tumors of the lacrimal gland fossa comprise roughly 10% of all orbital masses.[1] There are a wide variety of etiologies for these masses, including infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic.[2] Furthermore, neoplastic lesions can either be benign or malignant. This activity will focus on benign lacrimal gland tumors. Since the lacrimal gland fossa is in the anterior superolateral orbit, space-occupying lesions of this area of the orbit typically cause inferior and medial globe displacement. Proptosis is not always seen but can be present if the posterior growth of a mass pushes the eye forward. Most benign lesions grow slowly and without pain, so these changes may manifest over long periods of time, averaging 1 to 2 years before diagnosis, compared to 6 months or less for malignant lesions.[3] Many patients report a vague asymmetry of the middle third of the face as their initial, primary concern. Occasionally, lacrimal gland masses are noted incidentally during a routine eye exam or on imaging for an unrelated issue.

Etiology

One way to classify benign lacrimal gland tumors is by their cell-type origin:[4][5]

Epithelial Tumors

Epithelial tumors are the most common type of tumor; roughly half of them are benign.[6] Of the benign causes, the vast majority are pleomorphic adenomas, or benign mixed tumors, most commonly located in the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland.[7] The next most common benign lesion is a lacrimal gland cyst, also known as a dacryops or lacrimal duct cyst. They are more commonly located in the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland but can also be seen in the orbital lobe.[8] Though most commonly idiopathic, some cysts have been associated with scarring and trachoma, chemical injury, or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Other epithelial lesions are much less common and include oncocytoma, myoepithelioma, cystadenoma, and Warthin tumor.

Lymphoid Tumors

Lymphoproliferative lesions in orbit are commonly located in or around the lacrimal gland. The benign proliferation of lymphoid tissue is termed reactive lymphocytic hyperplasia, or benign lymphoepithelial lesion, and accounts for around 6% of all biopsied orbital masses. Some cases of lymphoid hyperplasia have been documented in association with IgG-4-related disease.

Mesenchymal Tumors

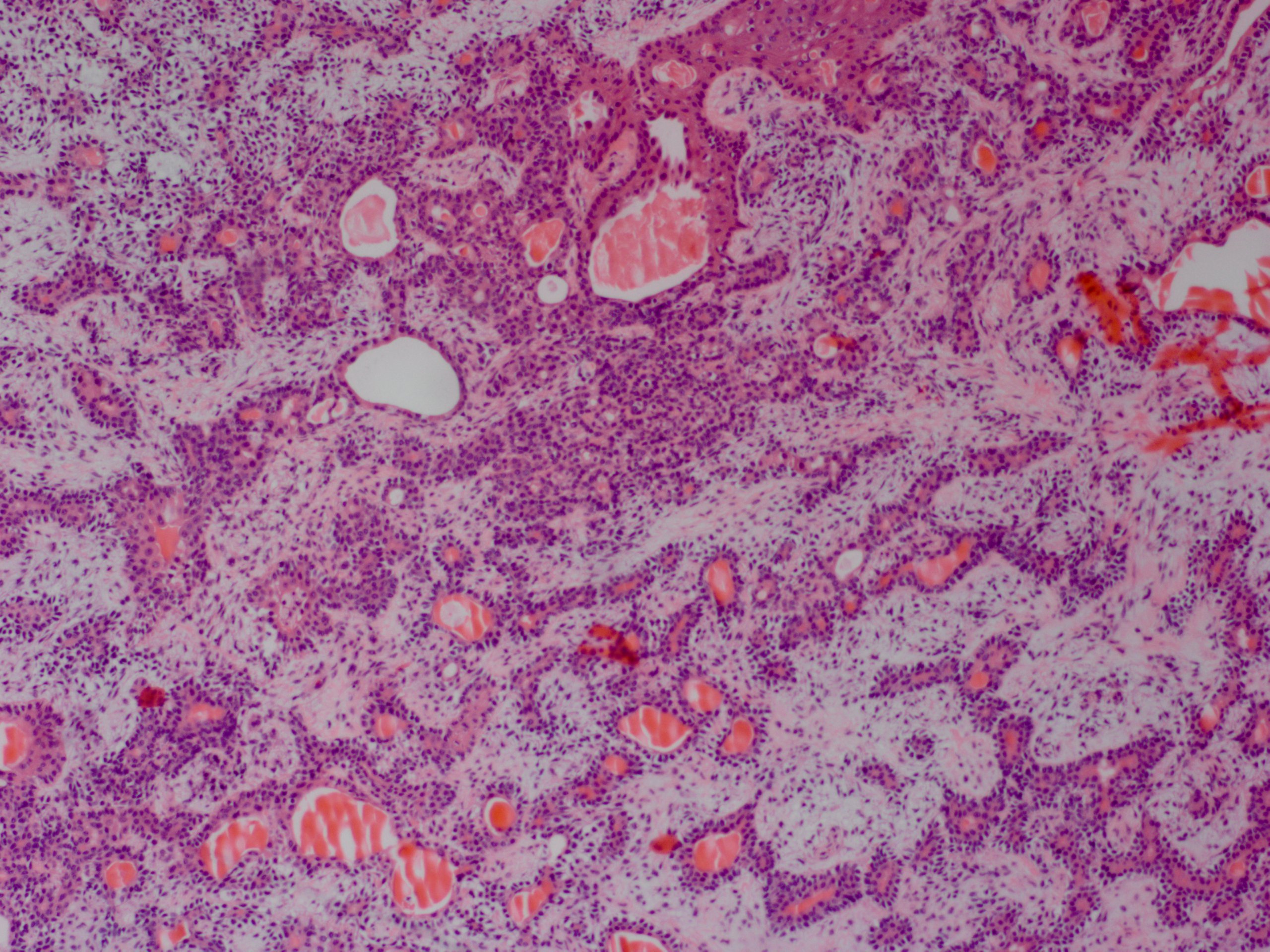

Mesenchymal tumors of the lacrimal gland are primarily vascular-type masses. It has been reported that the most common of these vascular tumors is angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Still, other lesions can also be seen, such as capillary and cavernous hemangiomas and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Other mesenchymal tumors include granular cell tumors, fibrous histiocytoma, solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma, neurofibroma (with or without systemic neurofibromatosis type I), and schwannoma.

Other unlisted benign tumors can exist but are exceedingly rare.[5][9]

Epidemiology

The benign lacrimal gland tumors listed above can occur at any age, though most commonly occur in adults as they approach middle age (around the fifth decade of life). In general, there is no sex predilection amongst different subtypes of tumors.[7] Specific risk factors for isolated benign lacrimal gland tumors are not established due to the overall rarity of lacrimal gland tumors. However, some systemic disorders lend to a higher risk of certain lesions (e.g., neurofibromatosis type I and plexiform neurofibroma of the lacrimal gland).

Pathophysiology

Tumors of the lacrimal gland are similar to tumors of the salivary glands due to their shared embryologic origin. Genetic studies for pleomorphic adenoma show multiple subtypes, including those that have rearrangements in the pleomorphic adenoma gene 1 (PLAG1) or high motility group protein gene 2 (HMGA2).[5]

Histopathology

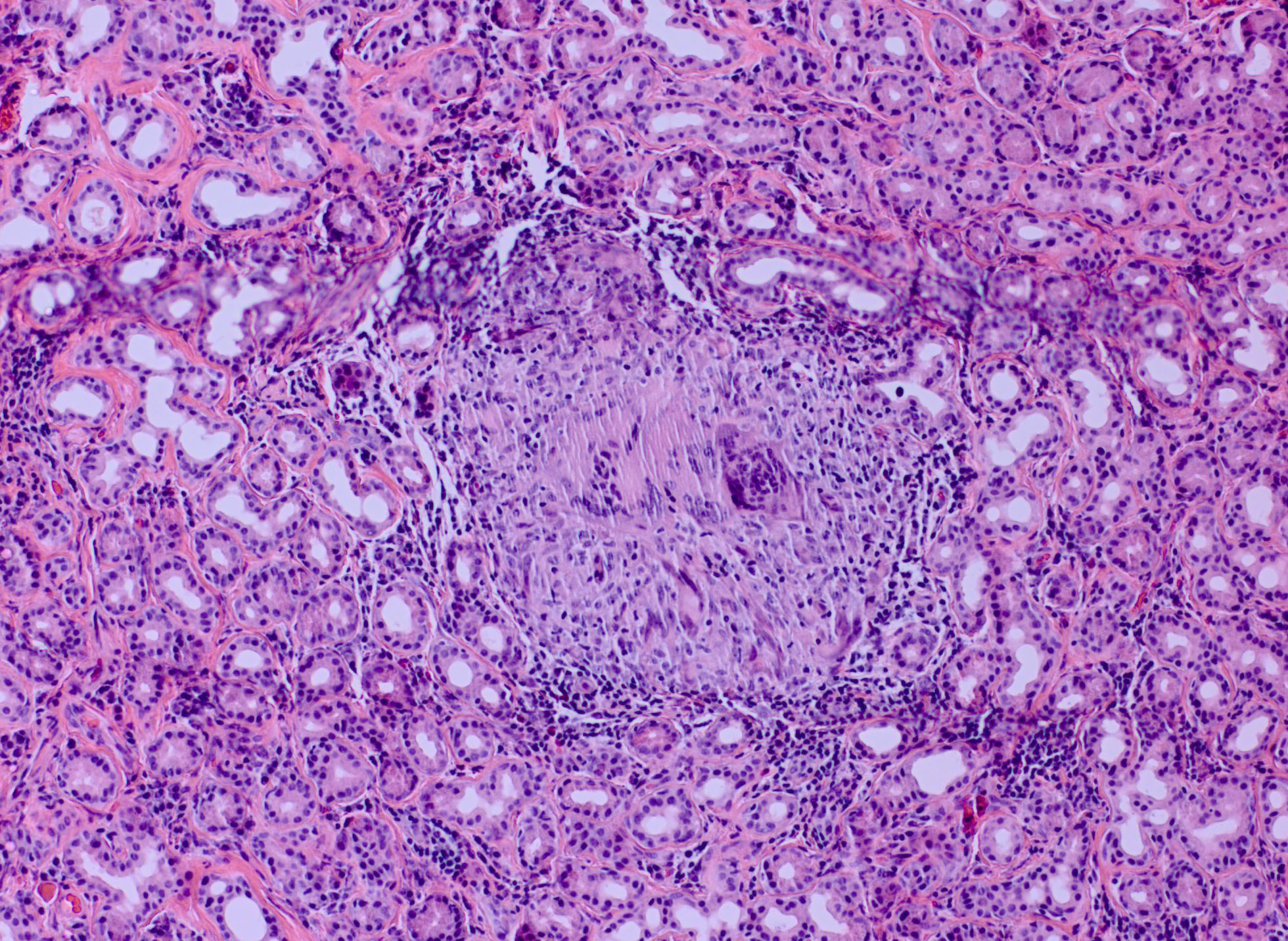

On histopathologic analysis, pleomorphic adenomas demonstrate proliferation of both epithelial and myoepithelial structures, arranged to form spindle and glandular/ductal structures with lumens. Surrounding this is a pseudocapsule of normal tissue, which may include areas of microscopic penetration of tumor cells.[4]

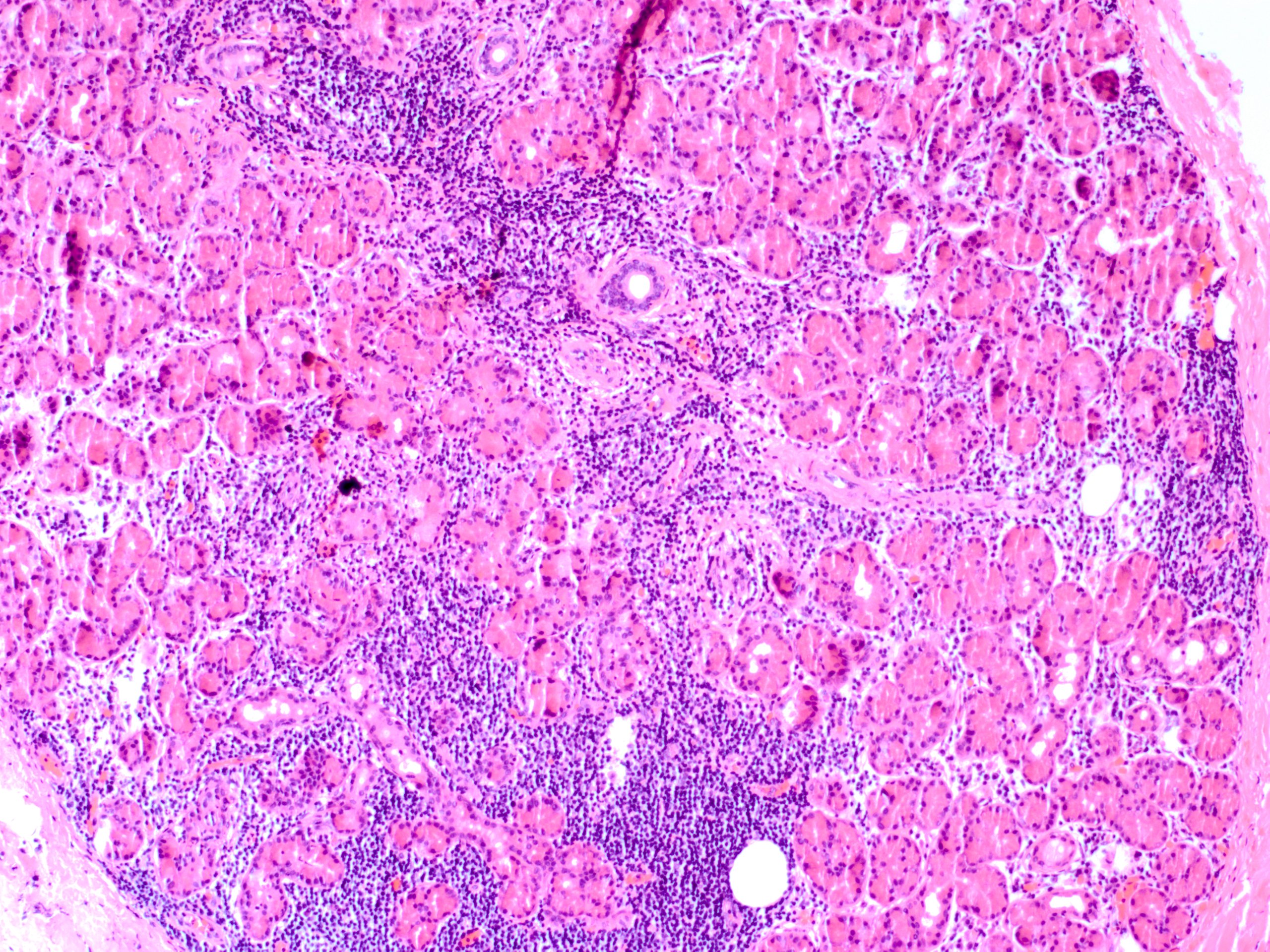

Dacryops is seen microscopically as a dilated lacrimal gland cyst lined by normal glandular epithelial cells.

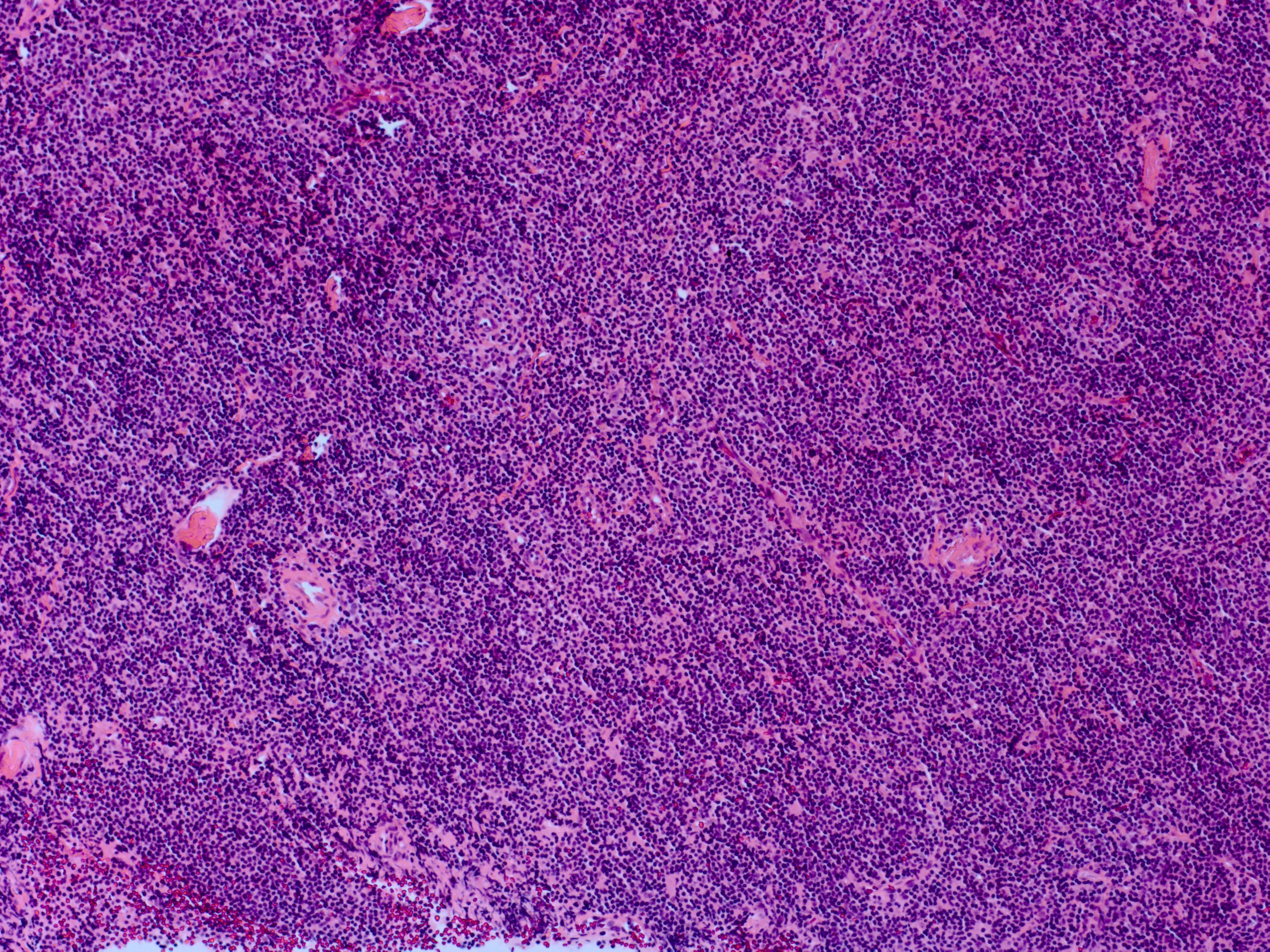

Benign lymphoid hyperplasia is a dense stroma of lymphocytes and macrophages without undifferentiated malignant cells. There are reactive lymphoid follicles similar to normal lymph nodes, with only mitotic cells isolated to the germinal centers.[10]

History and Physical

Demographic data is important to collect, including age, gender, ethnicity, and race. Systemic medical history is also vital to ascertain possible etiologies, specifically history of recent illness, history of autoimmune or inflammatory disease, history of cancer or chemotherapy and/or radiation, history of systemic immunosuppression, and history of prior trauma or surgery. A comprehensive review of systems may reveal potential systemic autoimmune or inflammatory disease associations.

A thorough orbital and ophthalmologic history regarding blurry vision, double vision, change in outward appearance or facial symmetry, pain, light sensitivity, pain with eye movement, eyelid swelling or redness, discharge, tenderness, tearing, and dryness should be obtained. Consider comparing old patient photographs to evaluate for changes in globe position (dystopia), eyelid position, or contour.

A complete, dilated ophthalmic examination by an ophthalmologist or oculoplastic and orbital surgeon should be performed. This includes checking visual acuity for decreased vision, pupillary light reflexes for adequate responses and the presence of a relative afferent pupillary defect (rAPD), and other signs of optic neuropathy, such as color vision deficits red light saturation, and visual field defects. Evaluating ocular motility can provide the degree of any limitations and the presence and pattern of diplopia. It is also prudent to evaluate any globe malposition, especially inferiorly and medially for lacrimal gland tumors, and to perform exophthalmometry to evaluate proptosis. Digital palpation of the eyelid/orbit and lacrimal gland may identify masses, and there may be resistance to retropulsion of the globe if a mass is present. Palpation of regional lymph nodes can reveal lymphadenopathy. Hypoesthesia of the first or second divisions of the trigeminal nerve should be checked to evaluate for orbital nerve compression or invasion. Clinically, there may be eyelid edema, erythema, or warmth and a directly visualized enlarged and tender lacrimal gland with secondary upper lid ptosis or S-shaped lid deformity. The conjunctiva may be injected, especially overlying the area of the lacrimal gland. An anterior and posterior segment exam is also needed to evaluate for signs of uveitis.

Evaluation

It may be difficult to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions based on clinical evaluation alone. The onset and progression may hint one way or another, as benign lesions tend to grow slower. The presence or absence of pain can also help predict the nature of the offending lesion, as the most common malignant lesion, adenoid cystic carcinoma, can exhibit perineural invasion. Usually, orbital imaging is helpful and often necessary to confirm and characterize a possible orbital lesion. Characteristics to discern are whether the tumor is solid vs. cystic, well-defined vs. infiltrative, the presence or absence and amount of calcification, the presence of fat or fluid, bony remodeling or destruction, and contrast enhancement.[11][12]

Computed tomography (CT) is quick, widely available, cost-effective, and especially helpful for lacrimal fossa anatomy. It is widely considered as the initial imaging modality of choice for lacrimal gland lesions, especially if a benign tumor is suspected.[4] It can identify the presence and size of a mass and the effects on surrounding structures such as the bone (most importantly), extraocular muscles, and the globe. Contrast administration is also helpful to look for enhancing lesions. CT scans also readily show calcification within a lesion, which can help differentiate the offending mass.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more expensive, harder to obtain, and a longer duration study, but it gives superior soft tissue detail. The various image processing sequences available allow for detailed characterization of the mass in question. Unlike CT, MRI has limited bone visualization but can better evaluate tumor involvement of orbital nerves, important for adenoid cystic carcinoma.[11]

Some cases may require both CT and MRI imaging and a biopsy before further management decisions.

The PLAG1 mutation is also associated with salivary gland tumors. Evaluation should include screening for these.

Treatment / Management

For most tumors, there is no purely medical treatment. The major exception is the systemic treatment of lymphoid hyperplasia, as discussed below. Most tumors require either biopsy or excision as initial management. Depending on the identity of the tumor, some patients will then need extended treatment even after the initial surgery. Rarely, a small, stable, or slow-growing lesion may be monitored without surgical intervention if there are no concerns of possible malignancy or if surgery is unable to be performed.

Pleomorphic adenoma is treated with complete surgical excision, including the surrounding pseudocapsule. This may be accomplished through an anterior orbitotomy or a lateral orbitotomy approach. The lateral orbital wall may need to be removed to provide full access to the tumor and allow for easy delivery of the tumor from the orbit without the risk of capsule rupture.[4] It is crucial to handle the tumor carefully and not rupture the capsule, as incomplete excision poses the risk of tumor recurrence and/or malignant transformation.[13][6]

Most well-circumscribed and supposed benign lesions are treated similarly to pleomorphic adenoma and excised completely. It has been suggested that incisional biopsies can be considered in unclear or equivocal cases. Even for pleomorphic adenoma, recurrence, and transformation risks are negligible if the surgical tract is also excised at the time of bulk tumor removal.[14]

Dacryops can be monitored but may become symptomatic with growth causing diplopia, infection of the cyst contents, or be aesthetically displeasing to the patient. In these cases, the cyst can be removed by excision or marsupialization. The most common approach is transconjunctival through the superotemporal fornix, given direct access to the lacrimal gland. Still, care needs to be taken to preserve the lacrimal gland ducts, especially for palpebral lobe lesions.[8] Direct aspiration or drainage is usually only temporarily effective as the lesions recur soon after.[6] In cases where the cyst is associated with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, a transcutaneous approach can be considered to reduce trauma to and subsequent scarring of the conjunctiva.

Lymphoid hyperplasia is usually treated without surgery. Commonly, the initial treatment is high-dose systemic steroids, with or without concurrent radiation therapy. In some cases, rituximab has been used to control lymphoproliferative lesions. Rarely, lesions can be removed or debulked surgically.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

In addition to the benign lesions above, other etiologies can present as lacrimal gland fossa lesions. Two major categories for these other causes are inflammatory lesions and malignant tumors. Altogether, inflammatory lesions make up the most common cause of lacrimal gland enlargement.[6] The single most common etiology is dacryoadenitis, which can be unilateral or bilateral and inflammatory or infectious.[2]

Inflammatory Lesions

- idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI) (also known as orbital pseudotumor) and nonspecific orbital inflammation (NSOI)

- IgG-4 related disease

- sarcoidosis

- granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- dacryoadenitis

- Sjogren syndrome

- thyroid eye disease (TED)

Malignant Tumors

- adenoid cystic carcinoma

- lymphoma

- ductal adenocarcinoma

- metastasis

Lesions Found Near the Superolateral Orbit Often Confused for Lacrimal Gland Tumors

- Epidermoid or dermoid cyst, commonly found at the frontozygomatic suture and may have an intraorbital component

- Prolapsed orbital fat, causing fullness of the lateral upper lid or a mass in the superotemporal fornix

- Dermatolipoma, commonly seen under the superotemporal conjunctiva

- The prolapsed lacrimal gland gives the appearance that it has been displaced by a mass

Lacrimal gland enlargement can also be seen in amyloidosis. Though rare, amyloid deposition in orbit, including the lacrimal gland, is usually due to a localized disease process rather than associated with systemic amyloidosis.[15]

Prognosis

The prognosis of benign tumors is usually quite good. Most of the morbidity from these lesions derives from their space-occupying nature and their effects on surrounding tissue. Large lesions can cause a disfiguring appearance from proptosis or globe displacement. Visual changes can occur due to diplopia from globe displacement or decreased mechanical effectiveness of the extraocular muscles. Direct compression of the globe can lead to blurry vision from deforming the refractive shape of the eye. Pressure on the optic nerve can lead to optic neuropathy and decreased visual acuity, color vision changes, and visual field defects. At times, the tumors can be related to systemic disease (e.g., neurofibroma with neurofibromatosis type 1), where overall patient prognosis depends on the severity of the systemic disease.

Concerning pleomorphic adenoma, recurrence of the tumor has been associated with malignant transformation, which can negatively affect long-term ocular and patient prognosis. This risk is increased in cases of multiple recurrences and with the increased age of the patient.

Dacryops have a high recurrence rate if treated with simple aspiration and drainage.[6] Even with excision, some lesions do recur if they were incompletely excised.

Complications

Complications of benign tumors are mostly related to the direct mass effect on surrounding tissues, as described above. If surgical biopsy or excision is pursued, then complications are related to the surgery performed and the techniques utilized. For anterior or lateral orbitotomies, the main complications of note include orbital hemorrhage, postoperative orbital cellulitis, damage to the extraocular muscles, globe, or optic nerve, dryness from decreased lacrimal gland function, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) leak, or recurrence of the tumor. Close monitoring after orbital surgery is crucial to managing these sight-threatening complications in a timely manner.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The management of tumors in an area as important as the orbit can be quite complicated. A thorough discussion is necessary to inform the patient of the potential causes, treatments, adverse events, and prognosis of the disease processes involved. Whenever cancer is a possibility, it is critical to approach the patient with compassion and empathy. At times this may necessitate multiple discussions so the patient can process the information and make an informed decision. The risks, benefits, and alternatives of any treatment (or lack of treatment) should be explained. The emotional and psychological impact of the diagnoses involved and the treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, long-term monitoring for recurrence, etc.) and especially any complications that arise may require interprofessional attention from a primary care provider, oncologist, psychologist, or psychiatrist.

Pearls and Other Issues

When evaluating any patient with an orbital mass, it is important to keep a broad differential diagnosis. A thorough history and clinical exam are paramount for determining risk factors for various disease processes and guiding the acuity of diagnostic workup and treatment. Inflammatory signs are not often seen with tumors and may indicate infectious or inflammatory dacryoadenitis. Pain or hypoesthesia is often an indicator of malignancy, as most benign lesions are painless. Imaging is equally important in diagnosis and in the decision-making process for treatment; it can aid with surgical planning.

| |

Pleomorphic Adenoma

|

Nonspecific Orbital Inflammation (NSOI) |

| Age of onset |

5th - 6th decade |

More prevalent in adults |

| Gender |

No preponderance |

Females |

| Associated Pain |

No |

Yes |

| Duration of onset |

Indolent |

Acute |

| Histopathology |

Ducts & myxoid stroma

Pseudoencapsulated

|

Polyclonal infiltrate |

| Treatment |

Excisional biopsy |

Steroid

Orbital radiation

|

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

From start to finish, the journey from clinical evaluation to work up, then diagnosis to management, and then monitoring treatment response to managing complications requires a large, multi-disciplinary team of administrators, staff, technicians, nurses, and doctors. Effective communication is necessary to promote the efficient use of medical resources and provide a smooth experience for the patient. [Level 4]