Continuing Education Activity

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is an inflammatory condition and affects the juxtalimbal cornea. There is a complex interplay between host autoimmunity, the anatomy and physiology of the peripheral cornea, and the environment. The underlying cause could be local or systemic, infectious or noninfectious. Progressive stromal lysis can cause corneal perforation, which is an emergency. PUK occurring in patients with an underlying autoimmune disease indicate significant morbidity and mortality. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of peripheral ulcerative keratitis and describes the role of the healthcare team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology of peripheral ulcerative keratitis.

- Describe the risk factors for developing peripheral ulcerative keratitis.

- Summarise the classic patient history, presentation, and physical examination findings associated with peripheral ulcerative keratitis.

- Describe the management considerations and goals for patients with peripheral ulcerative keratitis.

Introduction

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) affects the juxtalimbal cornea and classically presents with epithelial defect and stromal lysis. This inflammatory condition results in a complex interplay between host autoimmunity, the anatomy and physiology of the peripheral cornea, and the environment. The underlying cause could be local or systemic, infectious or noninfectious. PUK can be due to vasculitides and collagen vascular disease; rheumatoid arthritis (RA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can account for up to 53% of PUK cases.[1] PUK in scleritis is a poor prognostic factor. Progressive stromal lysis can cause corneal perforation, and in patients with an underlying autoimmune disease indicates significant morbidity and mortality.

PUK without systemic association is known as Mooren's ulcer (MU) and contributes to 31.5% of PUK causes.[2] Bowman first described it in 1849, followed by McKenzie in 1854, as an "ulcus roden" of the cornea.[3] Mooren's ulcer occurs in the absence of scleritis and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Clinical signs begin in the peripheral cornea and progress centrally and circumferentially, with a distinctive overhanging edge.

PUK is important to diagnose as it can be the first presenting feature of a life-threatening systemic disease. Meticulous clinical investigation and multi-disciplinary management are required to ensure safe patient outcomes.

Etiology

Table 1 summarises the variety of ocular (local) and systemic disorders that can lead to PUK.[3] Almost half of all noninfectious cases of PUK are associated with a connective tissue disorder, of which rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common. In RA, PUK affects both eyes in nearly half of all cases in later stages of the disease. Tauber et al. report RA to be associated with 34% of eyes with noninfectious PUK.[4] PUK is also a relatively common presenting feature for GPA, which is a systemic vasculitis that affects the sinuses, nose, throat, lungs, and kidneys. GPA-associated PUK is due to a necrotizing vasculitis affecting the anterior ciliary arteries and/or perilimbal arteries.

Infections can occur in the peripheral cornea without being defined as PUK. PUK is defined as having crescentic stromal thinning and inflammatory cells in the juxtalimbal cornea, with the presence of an epithelial defect. It is important to rule out infection as a cause because these make up 19.7% of all PUK cases.[2] PUK can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, Acanthamoeba spp, etc.

|

Systemic Causes

|

Ocular Causes

|

|

Infection:

- Varicella-zoster

- Viral hepatitis

- Tuberculosis

- Syphilis

- Lyme Disease

- Salmonella gastroenteritis

- Bacillary dysentery

- Gonococcal arthritis

- Cat scratch disease

- Parasitic infections

- Parinaud's oculoglandular fever

Autoimmune:

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Granulomatosis with polyangitis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Microscopic polyangiitis

- Churg-Strauss syndrome

- Sjogren's syndrome

- Sarcoidosis

- Relapsing polychondritis

- Behcet's disease

- Temporal arteritis

- Takayasu arteritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Dermatological:

- Acne rosacea

- Cicatricial pemphigoid

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

Other Systemic:

- Malignancies

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Iatrogenic drugs

- Gout

|

Infection:

- Staphylococcus

- Streptococcus

- Gonococcus

- Moraxella

- Hemophilus

- Herpes simplex

- Herpes zoster

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Filamentous fungi

- Dematicious fungi

- Acanthamoeba

- Epstein Barr virus

- Pythium insidiosum

Autoimmune:

- Mooren's ulcer

- Allograft rejection

- Autoimmune hepatitis

Trauma:

- Corneal penetrating injury

- Chemical injuries

- Thermal burns

- Radiation injuries

- Eyelid/margin abnormalities

- Ectropion, entropion

- Eyelid tumor

- Trichiasis

- Lagophthalmos

Neurological:

- Metaherpetic

- Xerophthalmia

- Neuroparalytic

Iatrogenic:

- Post-LASIK

- Post-Trabeculectomy

|

Table 1. Causes of PUK.

Mooren Ulcer

This is a diagnosis of exclusion and often is associated with severe pain.[5] Complications such as anterior uveitis, secondary infection, cataract, glaucoma, and corneal perforation in 35 to 40% of patients can develop. Three clinical subtypes have been described by Watson and colleagues.[6]

Type 1

- Unilateral

- >60 years of age

- Females

- Severe pain

- Rapid progression

- Poor prognosis, recurrence

- Complications rare

Type 2

- Bilateral

- Young (14-40 years)

- Males

- Mild to moderate pain

- Slow progression but aggressive initially

- Poor prognosis, recurrence

- Complications common

Type 3

- Bilateral

- Middle-aged (mid-50s)

- No gender predilection

- Mild pain

- Slow progression

- Better prognosis, recurrence rare

- Complications rare

Epidemiology

In the United Kingdom, estimates for PUK incidence range from 0.2 to 3 patients per million annually.[7][8][9] Females are more likely to be affected generally, although this is reversed for Mooren ulcers.[10] There is no good evidence on a racial or ethnic predilection for PUK; this will be affected by the associated cause, as does the age at initial presentation. Classification is generally clinical because this will enable clinicians to choose appropriate investigations and treatments to target the underlying etiology.

Pathophysiology

Several significant differences between the central and peripheral cornea make it susceptible to inflammation, ulceration, and furrowing. The peripheral cornea is the transition zone between cornea, conjunctiva, episclera, and sclera with a combination of histologic features.[11] There is reduced neural innervation and sensitivity in the peripheral compared with the central cornea.[12] The thickness of the peripheral cornea is greater at around 1000um compared with the central cornea of 550um. Epithelial cells are tightly adherent to the corneal basement membrane and stroma to a greater degree in the periphery.[13]

The reservoir of corneal epithelial stem cells and mitogenic activity of corneal endothelial cells are also highest in the peripheral cornea.[12][13] It has been hypothesized that an imbalance between collagenase and their tissue inhibitor activity leads to loss of corneal integrity and increased corneal matrix turnover. Increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) that cause extracellular matrix degradation and decreased tissue inhibitor of MMP (TIMP) can cause an increase in keratolysis.[14][15]

The central cornea is avascular and derives most of its nutrition through tear film and aqueous humor. In contrast, the peripheral cornea has a well-developed vascular and lymphatics supply, with perilimbal vessels extending 0.5mm into the cornea.[16] This is a source of immunoglobulins, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and other immune cells that mediate an inflammatory process.[17]

A combination of humoral and cellular immune mechanisms is involved in PUK. Autoantibodies and self-antigens combine to form immune complexes that activate B cells and complement proteins in PUK secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. B cells can further stimulate T cells to secrete cytokines associated with rheumatoid arthritis. The combination of angiogenesis and immune cell clusters contribute to pannus formation in PUK.[18]

History and Physical

PUK is usually unilateral but sometimes bilateral at the initial presentation.[2] Bilateral PUK is often asymmetrical and is associated with systemic disease. The patient will complain of ocular pain, photophobia, and tearing. The eye will be injected and red in appearance. Pain can be variable and is an important feature in PUK.[3] In Mooren ulcer, the pain is often out of proportion compared with the clinical signs. Reduction in vision is due to inflammation and can be mild or severe.

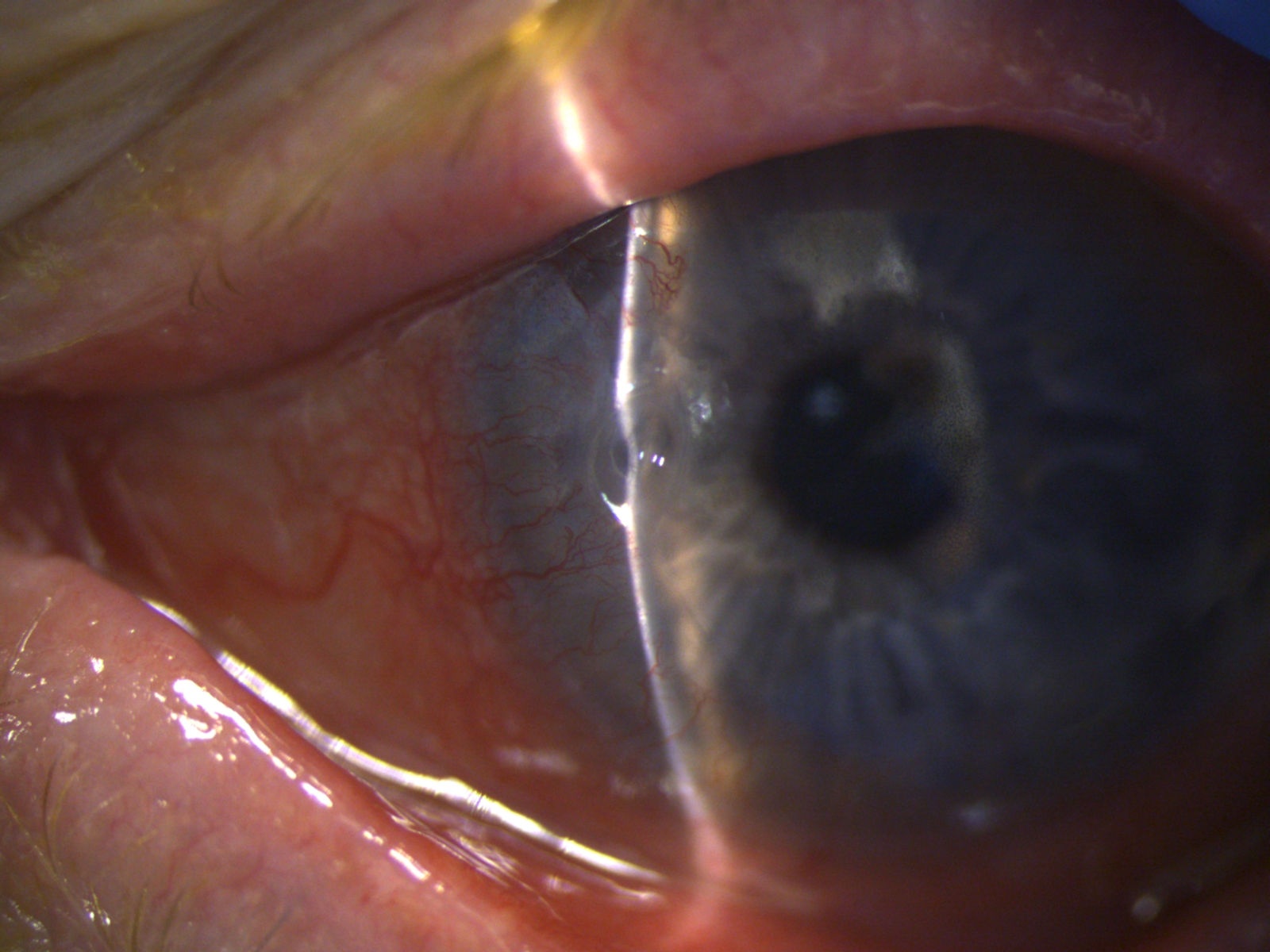

The classic clinical signs of PUK diagnosis are the combination of peripheral crescentic ulceration, superimposed epithelial defect, loss of stroma, and infiltrates at the limbus with an overhanging edge (figure 1). When PUK is associated with a systemic disease, the inflammation can also involve the surrounding conjunctiva, episclera, and sclera, with additional nodular or necrotizing scleritis. Persistent inflammation and stromal lysis can progress to corneal perforation, and clinically iris tissue will be visible as a "plug" in the perforation site. This is an ocular emergency. Chronic PUK with peripheral thinning and corneal vascularization will result in significant irregular astigmatism, scarring, and reduced vision.

Mooren's ulcer is PUK due to an unknown cause. Watson et al. described three clinical presentations (as above).[6]

Taking a detailed clinical history and examination can identify most causes of PUK. History should include asking about constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, gastrointestinal, respiratory, skin, cardiac, neurological signs, and symptoms.

Evaluation

A well-structured physical examination can yield clues to the systemic cause. Subcutaneous nodules in the upper and lower limbs, positive rheumatoid factor, and serum autoantibodies characterize rheumatoid arthritis, which is a common systemic cause of PUK. The presence of a saddle nose appearance and auricular pinnae deformity suggest relapsing polychondritis. This is a recurrent inflammatory disease of unknown etiology resulting in selective destructive inflammatory lesions of the cartilaginous structures.

Features of SLE include oral cavity mucosal ulcers, a malar facial rash, facial and scalp hypo/hyperpigmentation, and alopecia. A temporal headache with jaw claudication would be seen in giant cell arteritis. Raynaud phenomena can be present in SLE, Sjogren syndrome, and progressive systemic sclerosis. GPA usually presents in the fourth or fifth decade, with a male preponderance of 3 to 2. The characteristic triad of necrotizing, granulomatous, and vasculitic lesions occurs in the respiratory tract and kidneys (causing focal segmental glomerulonephritis).

Treatment / Management

PUK Management Aims and Strategy

A tailored approach is best, aiming to restore epithelial integrity, halt further stromal lysis, and prevent super-infections.[1] PUK patients with confirmed noninfectious etiology can be managed with a combination of topical lubricants, steroids, and oral steroids with collagenase inhibitors. The role of topical corticosteroids is controversial. If there is an underlying autoimmune disease, topical steroids can increase the risk of corneal perforation and should only be considered with caution.[16]

Systemic immunosuppressants can take 4 to 6 weeks to take effect; therefore, oral steroids will be necessary up to this point. Localized or systemic coexisting infection should be treated with the appropriate topical and/or systemic antimicrobials. Corneal scrapings should be undertaken at the initial presentation for gram staining, and microbiology evaluation and empirical therapy should be started, e.g., 4th generation fluoroquinolone monotherapy for bacterial keratitis. Once sensitivities have been established, the therapy can be adjusted as required. Topical steroids can be started to reduce the local inflammatory response after clinical improvement using antimicrobials. This should be delayed in cases of fungal infections. If suspecting herpetic cause, then topical acyclovir or ganciclovir are started. Systemic infection requires specific protocols and shared care with the relevant specialties.

Treatment Due to Etiologies

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Current first-line management is a systemic corticosteroid and a cytotoxic agent, e.g., methotrexate (MTX), along with topical lubricants to manage the ocular surface and encourage epithelial healing of peripheral corneal ulcers.[19] Systemic therapy is initiated with rheumatology or immunology teams. Second-line agents include azathioprine and cyclophosphamide and are used in severe, refractory PUK cases unresponsive to MTX.[20]

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Aggressive treatment is needed for PUK patients secondary to GPA and PAN. The first-line immunosuppressant agents for GPA include cyclophosphamide along with systemic corticosteroids ideally started early in the disease course. Rituximab or cyclophosphamide with or without other agents is the most effective at inflammation control in GPA-associated PUK.[21] Usually, cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids are used in the remission phase, with rituximab in the maintenance phase. If there is no response to cyclophosphamide, then treatment can be stepped up to rituximab. GPA-associated PUK presenting with necrotizing scleritis have a particularly poor visual prognosis as they are usually a sign of severe systemic vasculitis.[22]

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Foster et al. have suggested that systemic vasculitis only develops in the latter stages of SLE. Systemic corticosteroids and a cytotoxic agent are used in SLE-associated PUK. SLE patients with evidence of systemic vasculitis have significantly higher mortality.[23]

Pediatric Patients

MTX is considered a first-line immunosuppressant in PUK in pediatric patients with underlying systemic disease. If non-responsive, cyclosporine can be considered. There is a risk of teratogenicity during pregnancy, so these agents should be avoided. Oral steroids can be used with caution.

Patients on existing Immunosuppression Regimes

Firstly, infectious etiology should be excluded. Evaluation of potential systemic disease acute exacerbation should be undertaken. If there is a change in the systemic disease status, then the medical team can deploy a step up or maintenance strategy. Rheumatologists/immunologists will assess the clinical response to immunosuppression, which usually occurs after six months of initiation.[1]

Mooren Ulcer

The diagnosis of Mooren's ulcer is one of exclusion. The management strategy is a stepladder approach, with topical corticosteroids and cyclosporine (0.05% to 2%) initially, then progressing to limbal conjunctival resection/excision, systemic immunosuppressants, e.g., oral corticosteroids, MTX, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, etc., surgery including astigmatism treatment. Surgery alone is unlikely to be curative due to the underlying autoimmune pathophysiology.[24] An association between hepatitis C infection and a MU clinical phenotype has been reported.[25] Therapy with interferon α2b has resolved the corneal ulceration and induced hepatic disease remission.[26]

Surgical Management

There is a higher risk of PUK recurrence and graft melts with surgery, so this should be delayed until adequate control of inflammation is achieved.[27] Graft survival is less than 50% at six months, so multiple grafts are required in many patients.[20] Emergency surgical management depends on the indication. A therapeutic indication would be for ulcers extending circumferentially inducing corneal melt; tectonic indication would be for perforation or descemetocele; optical indication would be for visual rehabilitation.

The corneal defect size determines the surgical technique chosen. Multi-layered amniotic membrane transplant, conjunctival resection/recession/flaps could be an option in areas of corneal thinning.[28] Conjunctival resection removes the tissue supplying inflammatory mediators to the cornea. Lamellar patch grafts reduce graft rejection risk compared with a full-thickness patch or tectonic grafts.[29][30] Corneal glue (cyanoacrylate) with a bandage contact lens can be deployed if the perforation is less than 3mm in diameter.[31]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes all conditions that can present as peripheral corneal thinning and/or opacification, which are described in table 2. In marginal keratitis, there is often a clear cornea visible between the limbus and the infiltrates. Peripheral corneal degenerations are non-inflammatory, have intact epithelium, and do not have infiltrates.

| Inflammatory |

Non-inflammatory |

|

Staphylococcal marginal keratitis

Phlyctenulosis

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis

Infectious keratitis

Exposure keratitis

Trichiasis

Lid malpositions

|

Terrien marginal degeneration

Pellucid marginal degeneration

Senile furrows

|

Table 2. Differential diagnosis in PUK.

Prognosis

Patients with systemic associations and late disease presentation are harder to manage and generally will have higher morbidity and mortality. The combination of scleritis with PUK often indicates poor ocular and systemic prognosis.[8]

Corneal perforation results in a poor visual outcome despite response to treatment, with 65% of patients having a final vision of counting fingers or worse. It is also associated with higher one-year mortality of 24% in unilateral and 50% in bilateral corneal perforation cases.[9]

Complications

The most serious ocular complication is corneal perforation, which can occur in both eyes, and this has a detrimental effect on the final vision and can result in visual loss. Due to the systemic associations of PUK, there is a risk of mortality in PUK patients, especially if perforation occurs.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is an ophthalmic emergency as the patient is at risk of corneal perforation and blindness.[32] A multi-disciplinary approach to investigation and management is required, with collaboration between a number of specialists. The long-term need for immunosuppression can result in adverse side effects. Relapses can occur, and a clear management plan and good patient communication are necessary for safe outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis can be a diagnostic challenge. PUK patients can exhibit no systemic symptoms or signs which point to the underlying cause and require an interprofessional team consisting of an ophthalmologist, rheumatologist, dermatologist, internist, neurologist, pharmacist, nursing staff, and technicians. If there is significant visual loss, coordination with the eye clinic liaison staff and sight impairment registration will need to be undertaken. The etiology of PUK requires meticulous clinical investigation. Patient education is necessary on treatment compliance and the potential side effects of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressant agents. During prolonged treatment and monitoring disease activity, shared care with internists and rheumatologists can last for years after the initial diagnosis.