Continuing Education Activity

Iris cysts are rare ocular anomalies characterized by fluid-filled sacs within the iris. Although the exact cause of iris cysts remains unclear, they are often congenital or linked to trauma or inflammation. These cysts vary in size, shape, and location within the iris and can sometimes present with visual disturbances, elevated intraocular pressure, or discomfort. Although iris cysts are typically benign, they pose diagnostic and management challenges. Diagnosis commonly entails utilizing diverse imaging techniques such as slit-lamp biomicroscopy, ultrasound biomicroscopy, or optical coherence tomography during routine eye exams. Treatment approaches range from monitoring asymptomatic cysts to using medications or surgical interventions. Regular follow-up appointments are essential to monitor changes and ensure timely intervention if needed.

This activity emphasizes the etiology, evaluation, and management strategies of iris cysts, focusing on diagnostic imaging techniques, treatment modalities, and the significance of interdisciplinary teamwork of healthcare professionals in diagnosing and effectively managing this condition. This activity also develops proficiency in differentiating iris cysts from potentially malignant conditions such as iris melanomas through meticulous differential diagnosis, thereby promoting optimal patient outcomes and preserving ocular health. Moreover, this activity allows interprofessional healthcare professionals to explore a range of treatment strategies, from conservative monitoring to pharmacological (such as atropine) and surgical interventions (such as cyst aspiration, laser therapy, or excision for symptomatic cases) tailored to the cyst's size and impact on visual function.

Objectives:

Identify iris cysts through comprehensive eye examinations and optimal imaging techniques to accurately evaluate iris cyst characteristics.

Implement appropriate treatment strategies based on the size and impact of iris cysts on visual function, ranging from monitoring to medications or surgical interventions.

Assess changes in the size or characteristics of iris cysts through regular follow-up appointments, ensuring timely intervention if necessary.

Coordinate genetic testing and evaluation for associated conditions, such as ACTA2 gene mutations or thoracic aortic artery dissection, in patients with bilateral iris flocculations or other relevant risk factors.

Introduction

Iris cysts are rare ocular anomalies characterized by fluid-filled sacs within the iris. Although the exact cause of iris cysts remains unclear, they are often congenital or linked to trauma or inflammation.[1] Iris cysts can vary in size, shape, and location within the iris.[1] Although most iris cysts are typically benign and asymptomatic, they pose diagnostic and management challenges, leading to visual disturbances, increased intraocular pressure, or discomfort.[2] A careful differential diagnosis is essential to distinguish iris cysts from other conditions, such as iris melanomas, which can be malignant.[3][4]

Iris cysts are usually identified during routine eye examinations using diverse imaging techniques such as slit-lamp biomicroscopy, ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM), or optical coherence tomography to assess their characteristics. Treatment strategies for iris cysts depend on their size and impact on visual function. Asymptomatic cysts may undergo monitoring, while symptomatic ones may require management with medications, such as atropine, or surgical interventions, including cyst aspiration, laser therapy, or excision. Regular follow-up appointments are essential to monitor any changes in the cyst's size or characteristics. Early detection and prompt management are crucial to preserve ocular health and avert potential complications.[5][1]

Etiology

Iris cysts can be classified into 2 types—primary and secondary cysts. Primary cysts lack a recognizable etiology, whereas secondary cysts are associated with specific causes. Furthermore, iris cysts can be classified based on their tissue of origin.

Shields et al. introduced a classification system, delineating primary and secondary iris cysts as follows:[6][7]

Primary iris cysts: These cysts originate from the pigmented epithelium of the iris, which can occur centrally or pupillary, midzonally, or peripherally (iridociliary), and may be dislodged into the anterior or vitreous chamber. Primary iris cysts may also arise from the iris stroma and are categorized as congenital or acquired.

Secondary iris cysts: Secondary iris cysts encompass a variety of types, including epithelial cysts, which may occur due to epithelial downgrowth following an ocular surgery or trauma. Other types include pearl cysts, drug-induced cysts, parasitic cysts, and those associated with intraocular tumors such as medulloepithelioma, uveal melanoma, and uveal nevus.

Primary Cysts

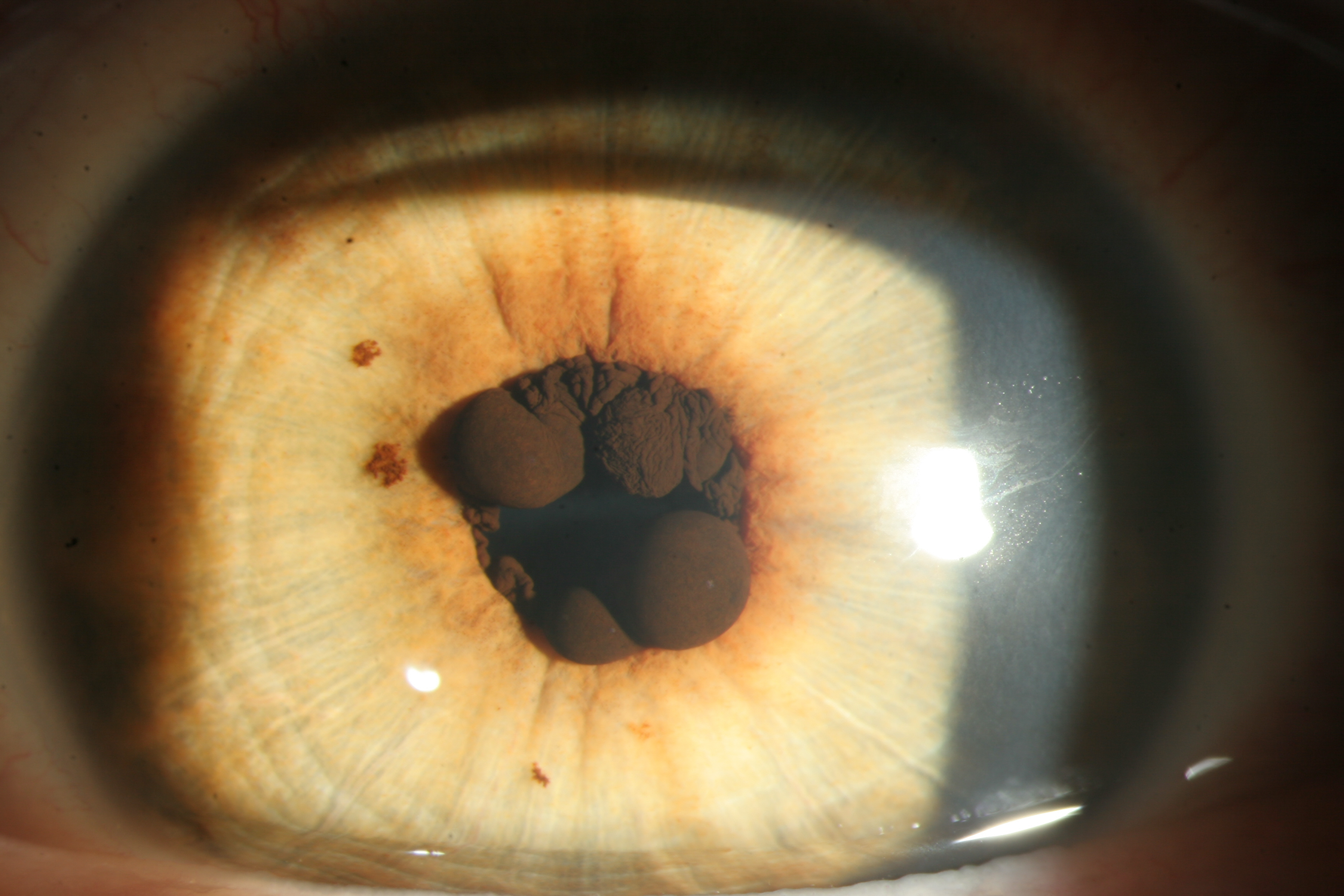

These cysts may originate from either the iris pigment epithelium or the iris stroma. Iris pigment epithelium cysts are additionally categorized based on their location (see Image. Pigmented Epithelial Cysts on the Iris).

The pupillary or central cysts involve the pupillary margin of the iris. These cysts are visible in an undilated pupil. These cysts are usually multiple, bilateral, round structures of variable size. These central cysts are projected into the pupil from the back surface of the iris. These cysts typically do not allow transillumination. These cysts can rupture, leading to linear stands that hang vertically and move with pupillary movements. The spontaneous rupture and reduction in size usually do not cause any apparent intraocular inflammation or other vision-threatening complications. These cysts can appear confluent, but around 8 distinct cysts can be noted in most cases.[6]

Iris flocculations are a subtype of bilateral multiple pupillary epithelial cysts. The pupillary cysts may spontaneously collapse and reform with wrinkling on the surface of the iris cysts. These may be associated with familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections due to mutation in the smooth muscle α-2 actin (ACTA2) gene.[8] The size of the pupillary cysts may fluctuate with time. There is usually no visual decline. The pupillary cysts are typically stable throughout life and do not need intervention.[9]

The midzonal pigment epithelial cysts (retro-iridic cysts) arise from the back of the iris (the pigmented epithelium) between the pupillary margin and the root of the iris (the midzone of the iris).[9] Pupillary dilation is needed to visualize these cysts. These cysts may be solitary or multiple and may involve both eyes. The shape of these cysts may change with pupillary dilation (round shape in mild pupillary dilation, fusiform or elongated shape in the mid-dilated pupil, and multiple round or fusiform cysts in the fully dilated pupil). These cysts usually do not transilluminate, though focal areas of pigment loss may allow some light transmission. The wall of the cyst may show undulations with ocular movements.

The iris cysts located near the junction between the iris and ciliary body are named iridociliary cysts. In a series of 62 patients, 45 had cysts occurring peripherally. These cysts typically occurred in patients in their twenties or thirties and were more prevalent in women than men, with 34 cases in females and 11 in males.[6] Unlike central and midzonal cysts, peripheral cysts are usually unilateral and solitary. The distribution of these cysts on the iris was mainly between the 2 to 4 o'clock and 8 to 10 o'clock meridians, with a preference for the inferotemporal side.[6] Peripheral cysts are subtle and often detected through slit-lamp examination as an anterior displacement of the iris stroma just below the horizontal meridian, with the best visibility using a vertical slit beam. Gonioscopy in maximal pupillary dilation shows a rounded anterior displacement of the peripheral iris stroma, with the cyst walls sometimes transmitting light, allowing visualization of the ciliary processes. UBM is crucial in the detection and documentation of such cysts. Among the cysts of the iris pigment epithelium, the peripheral cysts are the most common.

Dislodged epithelial cysts in the anterior chamber are usually unilateral, solitary, and pigmented cysts best visualized by gonioscopy. Often, they settle on the inferior angle of the anterior chamber and may exhibit fixed or freely mobile characteristics, particularly with head movement. Researchers believed that these cysts originate from the pigment epithelium of the iris, becoming dislodged from the posterior aspect of the iris and migrating to the anterior chamber through the pupil. Although these cysts generally do not transilluminate, areas of pigment loss may permit focal light transmission in some cases.[6][7]

Dislodged epithelial cysts in the vitreous cavity are usually solitary, pigmented, and unilateral round lesions. These vitreous cysts may move with ocular movements. However, typical wriggling movement of the cyst surface, as seen in cysticercus on exposure to the light of an indirect ophthalmoscope, is not seen in these vitreous cysts. Some vitreous cysts may allow visualization of structures behind them during the examination due to minimal pigmentation and transparency of the vitreous cyst.[6][7]

Stromal cysts lie anterior to the pigmented epithelium of the iris and can cause deformation of the iris. These are usually large solitary lesions with nonpigmented or transparent anterior and pigmented posterior surfaces. The content of the cyst is usually clear fluid. These cysts can be congenital or acquired. There is usually no history of trauma. However, a history of closed globe injury may be present without any evidence of open globe injury. In some cases, iris blood vessels may be seen in the anterior wall of the cyst. Unlike the iris pigment epithelial cysts, the stromal cysts may need treatment.[6][7]

Secondary Cysts

These cysts are categorized based on their pathophysiology. Implantation cysts may arise from a foreign body in the iris or through epithelial downgrowth following ocular surgery or trauma. Additionally, drug-induced cysts can occur, often associated with miotics such as phospholine iodide, pilocarpine, and the prostaglandin analog latanoprost.[10][11][12] Although these occurrences are rare, they represent recognized adverse effects. Inflammation and uveitis serve as uncommon causes of iris cysts, observed in conditions such as Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, and other cases of non-granulomatous anterior uveitis.[13][14] Parasites infrequently contribute to iris cysts, with cysticercosis being the most commonly associated pathogen.[15] Furthermore, intraocular tumors may present with cysts, originating from primary uveal tumors like uveal melanoma or nevus, or as an extension of periocular tumors and metastasis.[16][17]

Epidemiology

Iris cysts are uncommon lesions. No population-based study is available to estimate the prevalence or incidence of these lesions. The most extensive case series of 3690 iris lesions managed at a single center by Shields et al showed that 21% were cystic.[18] Of those, 87% were pigment epithelial cysts. Among the iris stromal cysts, congenital stromal cysts were more common in children.[18] Secondary cysts are more common than primary cysts. The secondary cysts are more common in males, which is likely linked to trauma and implantation cysts.[19]

Pathophysiology

Iris cysts arise from splitting the iris's epithelial layers or entrapment of surface ectodermal cells into the iris stroma. The implantation of the epithelium into the anterior chamber can progress with time, and acquired iris cysts have a higher rate of recurrences and complications. Acquired iris cysts are most often associated with ocular trauma.[20] On the other hand, the pathogenesis of primary iris cysts is still unclear, though these are typically stationary lesions, particularly those from the iris pigment epithelial layer.[2]

Histopathology

The type of iris cyst determines the observed histology. Central and midzonal iris pigment epithelium cysts comprise heavily pigmented columnar cells and do not transilluminate, whereas peripheral iris pigment epithelium cysts are partly lined by nonpigmented epithelium and usually transilluminate.[2] Stromal cysts have an epithelial lining that may be made of stratified squamous epithelium to monolayered cuboidal cells.[21] In the majority, they also have goblet cells. These features are typical of surface epithelium and suggest surface ectodermal origin. It is postulated that surface ectodermal cells may have been trapped in the iris stroma during embryogenesis.[22] Implantation cysts require epithelial cells to enter the anterior chamber. These may proliferate to form secondary iris cysts. The classic appearance is of concentric layers of stratified squamous epithelium.[2] They may contain goblet cells. These may or may not show a connection to the wound.

History and Physical

Primary iris cysts are often found incidentally. Many are asymptomatic unless they have enlarged to obscure the visual axis or cause other secondary complications.[23] In children, stromal cysts tend to enlarge and may cause amblyopia or strabismus, but stromal cysts usually remain stable in adults.[1]

Stromal cysts arise inside the iris tissue and often cause iris deformation. Congenital cysts are present in individuals aged 10 or younger and are usually unilateral and solitary. Acquired cysts present later in life and seldom require treatment. Free-floating cysts may appear in the anterior chamber or the vitreous cavity. Secondary cysts may have clues in the history, which may aid in classifying the lesion. It is not uncommon for patients to present with symptoms from secondary iritis, glaucoma (open and closed-angle), and cataracts.[2] Parasitic cysts may be asymptomatic or have low-grade iritis. Such a cyst may contain clear fluid and a freely moving scolex.[15]

Evaluation

To evaluate an iris cyst, performing a complete ocular examination of the anterior segment, including the gonioscopy and posterior segment, is essential. Slit-lamp and gonioscopic photos are invaluable in documenting cystic lesions (see Image. Cystic Iris Lesion). The midzone and peripheral iris cysts lie at the back side of the iris and need dilation with or without gonioscopy for better visualization.

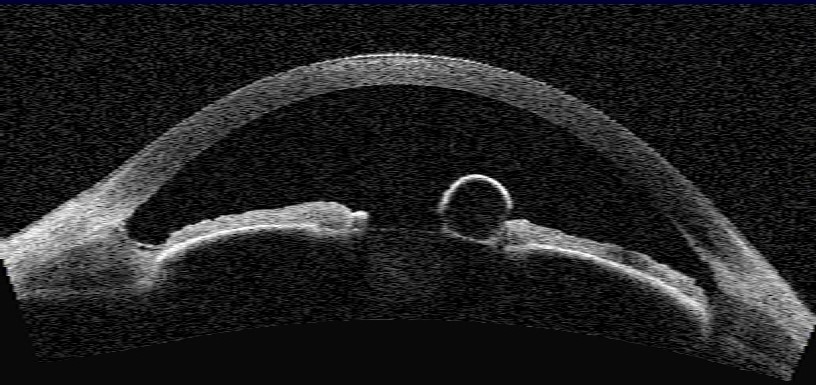

Anterior segment–optical coherence tomography: The anterior segment–optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) has been gaining traction in clinical use and assessing anterior segment lesions, including iris cysts. AS-OCT produces an image with a higher resolution than ultrasounds (see Image. AS-OCT of an Iris Cyst). However, its major drawback in this setting is shadowing caused by iris pigment epithelium and stroma, reducing the ability to discriminate cystic lesions from solid tumors in some cases.[24] Although the anterior surface may be visualized using the AS-OCT, the posterior extent may not be visible, and the content of the cyst may not be adequately elucidated.

B-scan ultrasonography: B-scan ultrasonography uses a 10-MHz probe to assess the lesion, including its cystic structure and posterior extension for the vitreous cysts.[25] The immersion B-scan technique is more helpful in evaluating the anterior segment.

Ultrasound biomicroscopy: Unlike B-scan ultrasonography, UBM employs a higher frequency (ranging from 50 to 100 MHz), providing superior image resolution, albeit with limited tissue penetration. UBM proves invaluable in assessing iris cysts and distinguishing them from solid uveal tumors. By delineating the anatomical structures and relationships of the lesion, UBM facilitates accurate evaluation.[26] The cystic or solid structure of the iris or ciliary body lesion is differentiated using the UBM. UBM evaluates all margins of the iris cyst. UBM using 35 MHz may image the ciliary processes, the ciliary body, and the peripheral iris cysts. The cysts appear as a round or oval lesion with a hyperechoic border and hypoechoic to anechoic cavity.

Fine needle aspirate: Fine needle aspiration may be indicated when other noninvasive evaluations fail to establish a diagnosis.[2]

Given the options, UBM is the gold standard in imaging an iris lesion. UBM is essential to perform adequate documentation to monitor progression carefully. In cases with bilateral iris flocculation, genetic analysis of the ACTA2 gene should be done. If the patient is positive for the mutation, the risk of aortic discussion should be explained. However, a study on patients with thoracic aneurysms associated with mutations of smooth muscle α-actin 2 (ACTA2) noted iris flocculation in only 6% of cases.[27]

Treatment / Management

In general, stable iris cysts that do not cause symptoms or secondary complications can be observed.[20] If an intervention is required, a step-wise approach is recommended.[2] Stromal cysts of the iris in children may grow and block the visual axis, causing amblyopia or other complications (eg, glaucoma) that necessitate intervention. On the other hand, stromal iris cysts in adults are usually stable and do not need intervention. Secondary iris cysts due to epithelial ingrowth following trauma (open globe injury) are challenging to treat. In children, these can proliferate and cause complications. Such cysts frequently need intervention, but these secondary cysts have a high tendency for recurrence. The primary pigment epithelial cysts of the iris usually do not require intervention. However, peripheral iridociliary cysts in the pigmented epithelium may enlarge, causing narrow angles and necessitating intervention. The pupillary and midzonal pigment epithelial cysts can also enlarge and obstruct the visual axis, causing visual decline and necessitating intervention.[9]

Laser treatment may be administered utilizing the laser properties of either photocoagulation (argon) or photodisruption (neodymium: yttrium aluminum garnet [Nd: YAG]).[28][29] An argon laser can be applied to the cystic wall and may stop the production of intracystic fluid.[30][31] The size may shrink, though recurrence is not uncommon after laser photocoagulation. A Nd: YAG laser can perforate the cystic wall (laser cystotomy).[32] The release of the intracystic fluid may cause inflammation and increased intraocular pressure. Recurrence of the cyst is an issue with laser therapy. The combination of the 2 lasers has been used by some clinicians successfully.

Fine needle aspiration of intracystic fluid to collapse the cyst presents a straightforward approach to managing large pigment epithelial cysts obstructing the visual axis.[9] This controlled method may prevent pigment release into the eye.[33] Specifically, for large iridociliary cysts causing angle closure, fine needle aspiration (following pupil dilation) may be preferred.[33] Peripheral cysts, situated behind the iris at the iris-ciliary body junction, may not be reachable for laser treatment.

Another effective treatment option involves fine-needle aspiration followed by the injection of a sclerosing agent. Common sclerosing agents include ethanol, mitomycin C, trichloroacetic acid, and 5-fluorouracil.[34][35][36] These agents will devitalize the cystic epithelium and goblet cells, which can either stabilize or involute the disease. Initially, the fluid inside the cyst is aspirated using a 27-gauge needle.[34] The position of the needle is not changed, and the syringe is replaced with another syringe with an equal volume of ethanol. The alcohol is slowly injected inside the cyst, and the ethanol is kept inside the cyst for 1 minute until the cyst wall becomes white, after which the alcohol is removed and the needle is removed. The anterior chamber is then washed thoroughly. One of the complications from fine-needle aspiration occurs when cystic contents are released in the anterior chamber, causing severe inflammation. In addition, recurrence of cysts and intraocular epithelialization could occur. Intraocular pressure may increase after the procedure. In some cases, repeat injections are needed.[34] Such therapy is reserved for stromal cysts of the iris, and a 3-way T-extension may be used for aspiration of cyst content and injection of sclerosing agent.[5]

Other surgical options include excision of the cyst alone or as part of a sector iridectomy or iridocyclectomy, depending on the location of the cyst. Surgical en bloc excision (with or without cryotherapy) is a more definitive treatment with the advantage of obtaining a tissue sample for histological analysis.[37] The surgery can be performed with a limbal or pars plana approach. However, it is usually reserved as a last resort, as it is associated with severe complications.[2]

The etiology of iris cysts can significantly influence their management approach. For drug-induced cysts, discontinuation of the causative medication often leads to resolution of the cyst. In cases of cysts secondary to miotic use, such as phospholine iodide, phenylephrine 2.5% eye drops may be used.[38] Secondary iris cysts related to uveitis may collapse after the control of uveitis.

Aggressive surgical intervention is often necessary for secondary cysts due to epithelial ingrowth (specifically after open globe injury or ocular surgery). The challenges include epithelial downgrowth, which is a recurrent and aggressive process.[39] The surgical procedure removes the cyst and the epithelial tissue completely while using viscoelastic materials to protect the cornea and other eye parts. Incomplete removal or rupture of the cyst can lead to recurrence and inflammation, while overly aggressive removal can damage the eye and impair its function.[40][32] For acquired implantation iris cysts, complete extended excision of the cyst with sectoral iridectomy has had success but should be reserved for cases not responding to less invasive interventions.[41]

Differential Diagnosis

It is essential to differentiate between different types of iris cysts and to rule out an intraocular tumor. A complete clinical examination and utilization of various imaging techniques are paramount. Some distinguishing features allow for differentiation between iris cysts and intraocular malignancy.[14] Malignancies tend to be solid, with irregular borders and a rough surface. They usually have surface vessels. On UBM, their walls are thicker and may have suspended particles. The posterior extension is common, as well as angle distortion.

The differential diagnosis of iris lesions can be cystic (21%) or solid (79%).[18] Cystic lesions most commonly arise from the pigment epithelium of the iris (18% of total iris tumors). Stromal cysts form a minority of the iris cysts (3% of total iris tumors).[18] Solid iris tumors are divided into melanocytic (68%) and nonmelanocytic (11%) tumors.[18] Melanocytic lesions include nevus, melanoma, melanocytoma, and melanocytosis. Nonmelanocytic iris tumors include non-neoplastic simulators, metastatic, vascular, epithelial, myogenic, choristomatous, fibrous, neural, xanthomatous, leukemic, lymphoid, and secondary lesions.[14][2][18]

Pars plana cysts are found in up to 18% of eyes and are more prevalent in older adults.[42] The walls of these cysts are usually nonpigmented and transparent. These may be associated with multiple myeloma, posterior uveitis, and retinal detachment. The cysts are filled with hyaluronic acid.[43] The fluid is collected between the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium and the pigmented ciliary epithelium or within the nonpigmented ciliary epithelium itself.[44] Typically, these are not thought to predispose to rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.[45] The relationship between these cysts near the ora serrata and iridociliary cysts needs further research.

Intraocular cysticercus is a differential diagnosis of the vitreous cysts. Live cysticercus shows undulating movements of the cyst wall, and the scolex may move specifically during examination with an indirect ophthalmoscope on exposure to light.[46] The ultrasonogram shows a cyst with a hyperechoic structure attached to the wall (scolex) in the cysticercus. Vitreous cysts appear as cystic structures with hypoechoic or anechoic intracystic content.[47]

Prognosis

The prognosis of an iris cyst depends on its nature and size. Primary cysts generally have a better prognosis than secondary cysts. Within the primary cyst group, pigment epithelial cysts have a better prognosis than stromal cysts. Other factors for poor prognosis include large size (occupying more than 50% of anterior chamber), apposition to cornea or lens, and younger patient age or reduced visual acuity at presentation.[19] There are no known racial or sex-related differences affecting prognosis.[14]

Complications

The severity of complications depends on the size, location, and relationship with other ocular structures. Recognized complications include obstruction of the visual axis, mechanical corneal decompensation, pigment dispersion, glaucoma (both open and closed-angle), recurrent iritis, and cataracts.[2][33] Complications can lead to strabismus and amblyopia in children.[2] Rare complications include vitreous hemorrhage and scleral cyst formation.[48][49]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients can be educated on the prognosis and the need to monitor for changes regularly. They should be instructed to return immediately should they note any significant new symptoms or changes in their vision. Specifically, stromal cysts and secondary iris cysts after trauma in children need close follow-up, and the patient's family should be educated about the potential chances of recurrence of the disease even after surgical interventions.[50]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Iris cysts are typically initially detected by optometrists or general ophthalmologists. During the early stages of diagnosis, it is crucial to ensure thorough documentation for effective monitoring of progression by either the eye care provider or a specialist over time. Documentation should include both written and photographic records to enable comparison as necessary. Secure digital information storage, such as photographs, UBM, and OCT, is recommended.

Interprofessional collaboration among healthcare providers is essential for the optimal management of iris cysts, involving anterior segment surgeons, glaucoma specialists, retina specialists, uveitis specialists, ocular oncologists, optometrists, and ophthalmic nurses to ensure the best outcomes. In addition, patients presenting with bilateral iris flocculations should undergo evaluation for thoracic aortic artery dissection and mutation of the ACTA2 gene.[51] Collaboration with an oncologist is advised in older patients with a recent onset iris lesion to exclude metastasis.[52]