Continuing Education Activity

Myasthenia Gravis is a neuromuscular disorder affecting muscarinic, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. It is a disease characterized by weakness and fatigability of the skeletal muscles. Managing a patient with this disorder is challenging, particularly in the perioperative setting. This activity reviews the anesthetic management of this disease and highlights the role the interprofessional team plays in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis.

- Review the clinical classification and risk factors associated with worsening clinical outcomes.

- Summerize the pre-operative evaluation of myasthenia gravis.

- Explain the anesthetic management of myasthenia gravis by an interprofessional team.

Introduction

Neuromuscular (NM) diseases are a common cause of morbidity and mortality. Myasthenia gravis (MG) is one such disease characterized by skeletal muscle weakness and fatigability. In essence, MG is an autoimmune disorder that results from the destruction of post-synaptic nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors located at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ).[1]

Classically, patients will display increased weakness at the end of the day, or after exercise or exertion, with a resolution of symptoms occurring after rest. Deep tendon reflexes are normal, and autonomic dysfunction is rare. Respiratory muscles often become of significant concern as the disease progresses. The significant effect the disease exerts on the body, as well as the medications often used to treat the disease, yield unique challenges to the anesthesia provider. One must take care throughout the perioperative period to provide the safest care for the patient. Please note, Lambert-Eaton and other myasthenic syndromes, as well as other neuromuscular disorders, will not be covered in depth here.

Function

Myasthenia gravis poses a number of challenges to the anesthesiologist. A firm understanding not only of the disease process but also pharmacologic issues pertaining to treatment is necessary. Greater than 85% of patients with MG are found to have nicotinic ACh-R antibodies, though it is notable that neuronal nicotinic receptors are left unaffected. This indicates the disease affects skeletal muscle only. Disease prevalence is estimated to be around 1 in 7500 patients. Disease incidence is most common in women in their twenties to thirties, whereas men show a bimodal age pattern, with a peak incidence in their thirties and again in their sixties. The course of the disease is marked by exacerbations and remissions. Many triggers of MG exist, including stress, surgery, and pregnancy as well as drugs (antibiotic, rheumatologic, cardiovascular) that can precipitate symptoms or lead to exacerbations.[2]

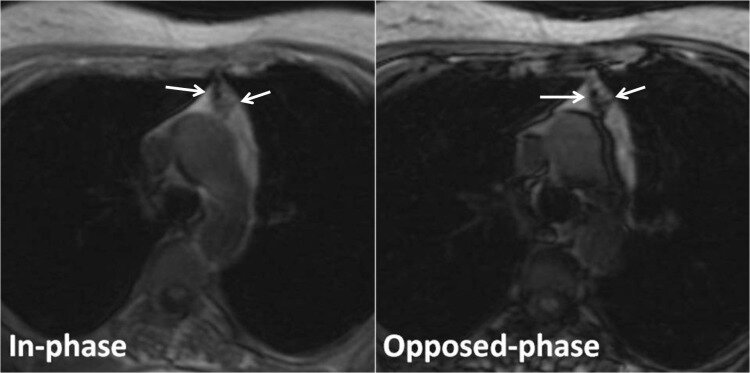

Classification is primarily based on whether the patient has ocular symptoms only or ocular symptoms with non-ocular weakness. Besides ptosis and diplopia, bulbar involvement is common, which will affect pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles. This can lead to issues with speech, dysphagia, and an increased risk of pulmonary aspiration. As the disease progresses, patients will often have more proximal muscle group and respiratory involvement. Patients with MG are at increased risk for postoperative respiratory failure. Myasthenic crisis, an exacerbation of the disease, can result in significant diaphragmatic weakness requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. Other autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), thyroid dysfunction, and diabetes mellitus (DM) are present in 10% of patients. Thymomas are common as well, and more than half of patients with MG show some level of thymic follicular hyperplasia. Thymectomy for patients with MG is a relatively common procedure to help relieve symptoms and provide remission for many patients.[3][4]

Issues of Concern

The pre-op evaluation should focus on which muscle groups are affected, the recent course of the disease, current pharmacologic therapy, and any comorbid conditions. Those with pulmonary or bulbar involvement are at increased risk for aspiration, and premedication with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), histamine-2 (H2)-blocker, or prokinetic agent (i.e., metoclopramide) can be helpful. Avoidance of calcium channel blockers and magnesium is beneficial to help muscle contraction integrity. The mainstay of treatment is acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (primarily pyridostigmine) to help increase acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ).

Patients should be instructed to continue their MG medication through the preoperative period. Postoperatively, the regimen should be re-started, especially for more generalized and severe diseases, as they are more likely to decline if treatment is withheld. If needed, the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor can be given parenterally, though these ought to be lowered to 1/30th the oral dose. Of note, excessive administration of these medications can lead to a cholinergic crisis marked by increased weakness with expected muscarinic effects of miosis, lacrimation, salivation, bradycardia, urination, and defecation. If in doubt about the etiology of such an episode, one can use an edrophonium test (Tensilon test) to help differentiate between a myasthenic vs. cholinergic crisis.

In a myasthenic crisis, strength will increase following the administration of edrophonium. If the Tensilon test is contraindicated, an ice-pack test can also be performed.[5] With more moderate to severe disease, immunomodulators such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, and corticosteroids are added. Patients who demonstrate respiratory and oropharyngeal weakness, or those displaying an increase in symptoms, should be given plasmapheresis or intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), especially if the patient is suffering an acute exacerbation. A discussion with the patient regarding the possible need for prolonged intubation after the procedure should take place. Other drugs that can potentiate weakness with these patients include cardiovascular and antiarrhythmic agents (i.e., beta-blockers, lidocaine, procainamide) and antibiotics (i.e., aminoglycosides).

The Levinthal scoring system involves a set of weighted risk factors that predict the increased likelihood for postoperative mechanical ventilation for patients with MG. This system was developed on patients undergoing transcervical thymectomy. However, these risk factors are now widely accepted for use in patients with MG undergoing other procedures requiring general anesthesia with paralysis. These factors can help serve as a guide for the clinician to focus on during the perioperative period.

Risk factors associated with an increased likelihood for postoperative mechanical ventilation include a duration of disease greater than 6 years, co-existing pulmonary disease, pyridostigmine dose exceeding 750mg per day, and a preoperative vital capacity of less than 2.9L. More recent studies have demonstrated that a history of prior myasthenic crisis and the presence of anti-ACh antibodies were positive indicators of the need for postoperative mechanical ventilation.[6][7]

Lambert-Eaton (LE) myasthenic syndrome is often mentioned in conjunction with MG, but it is its own distinct entity with a pathophysiology that differs from MG. The weakness associated with LE is due to antibodies directed against presynaptic calcium channels at the NMJ. Patients often show an improvement in muscle strength with repeated use, reflexes can be decreased, and males are more commonly affected than females. Proximal muscles are affected more in LE myasthenic syndrome than in MG. It is associated with small-cell lung cancer, and patients are often resistant to non-depolarizing neuromuscular blockers.[8]

Clinical Significance

Patients with MG are often more sensitive to the depressive respiratory effects of benzodiazepines and opiates. Caution must be exercised when giving these medications. Due to the decreased amount of ACh available, these patients tend to be resistant to depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents (i.e., succinylcholine) and very sensitive to the non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents (i.e., rocuronium), so care must be taken during the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia where paralytics are used.

Depending on the procedure, volatile anesthetics may provide sufficient muscle relaxation, and if possible, negate the need to give any neuromuscular blocking agents. If needed, a shorter-acting neuromuscular blocking agent is preferred. Physiologic stress is known to cause exacerbations of MG, and undergoing general anesthesia during surgery is a known source of physiologic stress. Multimodal anesthesia aids in maintaining adequate levels of analgesia and anesthesia for these patients. This approach can include using an epidural to help control the sympathetic nervous system response to surgery and anesthesia and decrease the overall stress response.[9]

No one specific volatile agent is clearly superior to others, and most are deemed safe overall. Patients with neuromuscular disorders, such as myasthenia gravis, will often show a pattern of restrictive lung disease as respiratory muscles become involved. The anesthesia provider should keep this fact in mind when providing positive pressure ventilation.

A complete reversal of rocuronium or vecuronium is possible with the advent of sugammadex while avoiding the downsides of giving neostigmine to this patient population. Several reports show variability in the reversal of neuromuscular blockade even with the use of sugammadex.[10] Therefore, the healthcare team must remain vigilant in monitoring the patient for any possible weakness. Awake extubation with confirmation of good ventilatory function is ideal in patients with MG who underwent general anesthesia using paralytic agents. Regardless, the extubation criteria are similar for all patients. Any other factors concerning the need for a slower emergence with ICU support must be weighed by the anesthesiologist and surgical team. Patients undergoing thymectomy may have shorter ICU stays and fewer postoperative pulmonary complications when extubated under 6 hours from the end of surgery.[11]

Other Issues

Special considerations must take place for the parturient with MG. These patients are prone to exacerbations and can show increased weakness in the last trimester to the early postpartum period. They are at increased risk of respiratory compromise, similar to other MG patients. Of the options available, epidural anesthesia is deemed relatively safe and may be preferred over spinal or general anesthesia. The maternal antibodies are passed through the placenta to the neonate. This causes neonatal MG and may present as feeding difficulties with respiratory dysfunction. The disease is transient in nature and usually lasts only a few weeks; however, it may necessitate intubation and mechanical ventilation to support the neonate early on.[12] The neonate may not manifest symptoms of transient MG for up to two days after birth, so monitoring for at least this period of time is prudent.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of patients with MG undergoing surgery is a team effort that should involve the surgeon, anesthesia provider, pharmacy, and nursing staff. A thorough understanding of the patient's current health and disease status should be discussed between team members. Management of the patient's disease should be optimized prior to undergoing any procedure, and this begins with the patient's primary care provider or neurologist.

Informed consent should include discussing the increased likelihood for postoperative mechanical ventilation and ICU admission with the patient. Postanesthesia care unit staff are crucial for monitoring for signs and symptoms of cholinergic or myasthenic crisis postoperatively. Additionally, active management of airway secretions is important to reduce aspiration events postoperatively. A collaborative model with timely and accurate communication will ensure the safest and best possible perioperative care for patients with MG.