Continuing Education Activity

Pericoronitis is a localized, intraoral soft tissue infection most commonly associated with erupting lower third molars. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are warranted as this condition can present with significant pain and discomfort, possibly affecting the quality of daily life. It can also lead to more severe infection if left untreated. This activity goes over the presentation, etiology, prevention, and treatment options of pericoronitis used by the interprofessional team.

Objectives:

Identify the signs and symptoms of pericoronitis.

Understand the etiology of pericoronitis.

Describe treatment options available for pericoronitis.

Explain how to minimize the risk of pericoronitis.

Introduction

Pericoronitis is an intraoral inflammatory process due to infection of the gingival tissue surrounding or overlying an erupting or partially erupted tooth. Pericoronitis is most commonly associated with the eruption of mandibular third molars, even though it can be seen with any erupting teeth. Symptoms of pericoronitis can significantly affect the quality of daily life. If left untreated, it can progress to life-threatening space infections, necessitating early identification, treatment, and prevention of the disease.

Etiology

The previously sterile space formed between the crown of a tooth and the dental follicle is exposed to intraoral microflora as the tooth erupts into the oral cavity. This small pocket that is surrounded by the soft tissue overlying the erupting tooth is difficult to clean. This forms an excellent environment for obligatory and facultative anaerobic bacteria to dwell. In addition, food can easily get impacted into this space, promoting bacterial growth and causing infection of the surrounding soft tissue, so-called pericoronitis. The microflora of pericoronitis is diverse and differs from pathogens that cause periodontitis. In a study of microbiota of pericoronitis, Actinomyces oris, Eikenella corrodens, Eubacterium nodatum, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Treponema denticola, and Eubacterium saburreum were present in high levels.[1] In short, pericoronitis results from bacterial overgrowth in a confined space that is exacerbated by poor cleansability.

A factor that can exacerbate pericoronitis is mechanical trauma from the opposing dentition. As maxillary third molars erupt, they can occlude onto the operculum overlaying the erupting mandibular third molars. Such repeated trauma can cause ulcerations and worsen the symptoms.

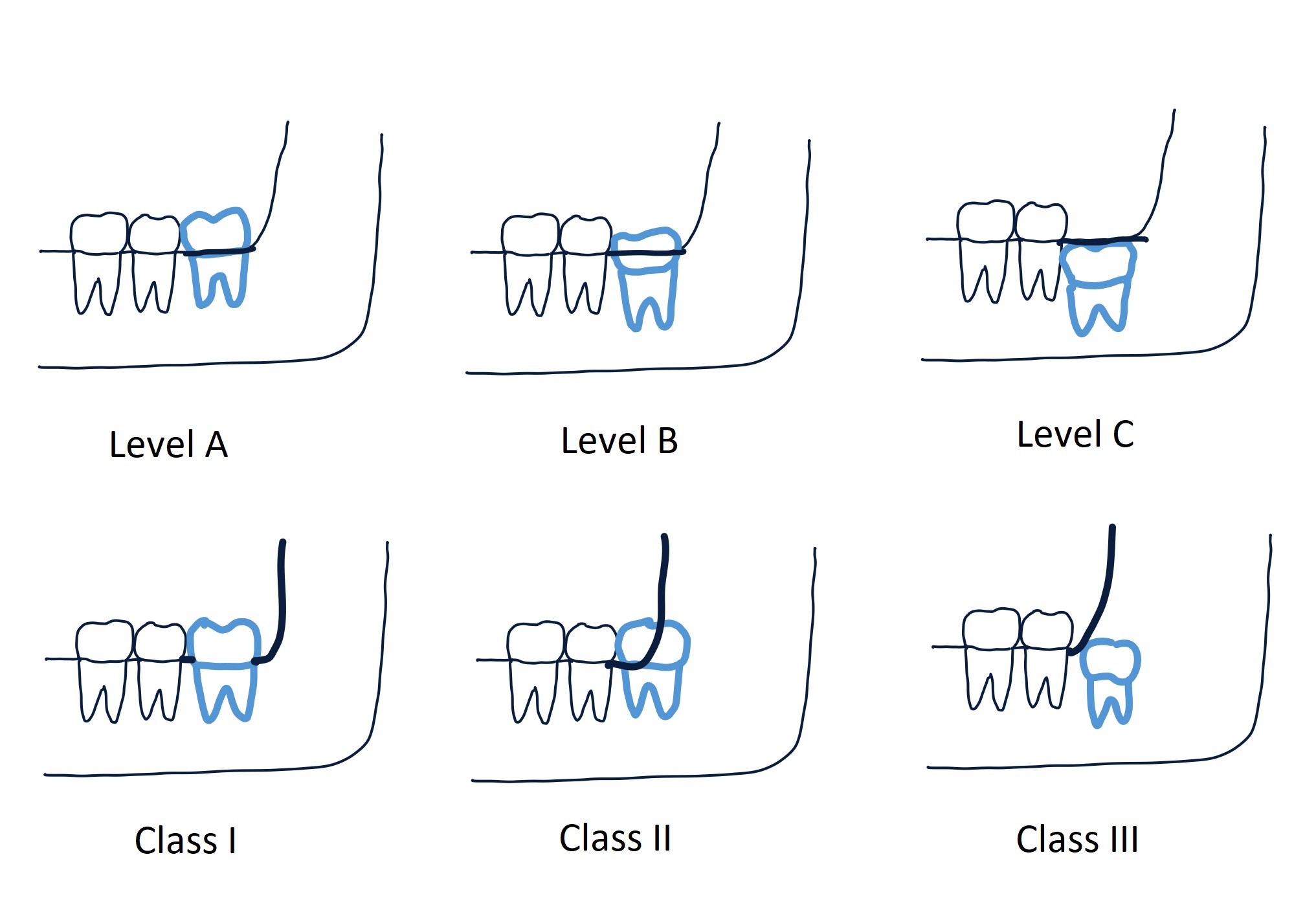

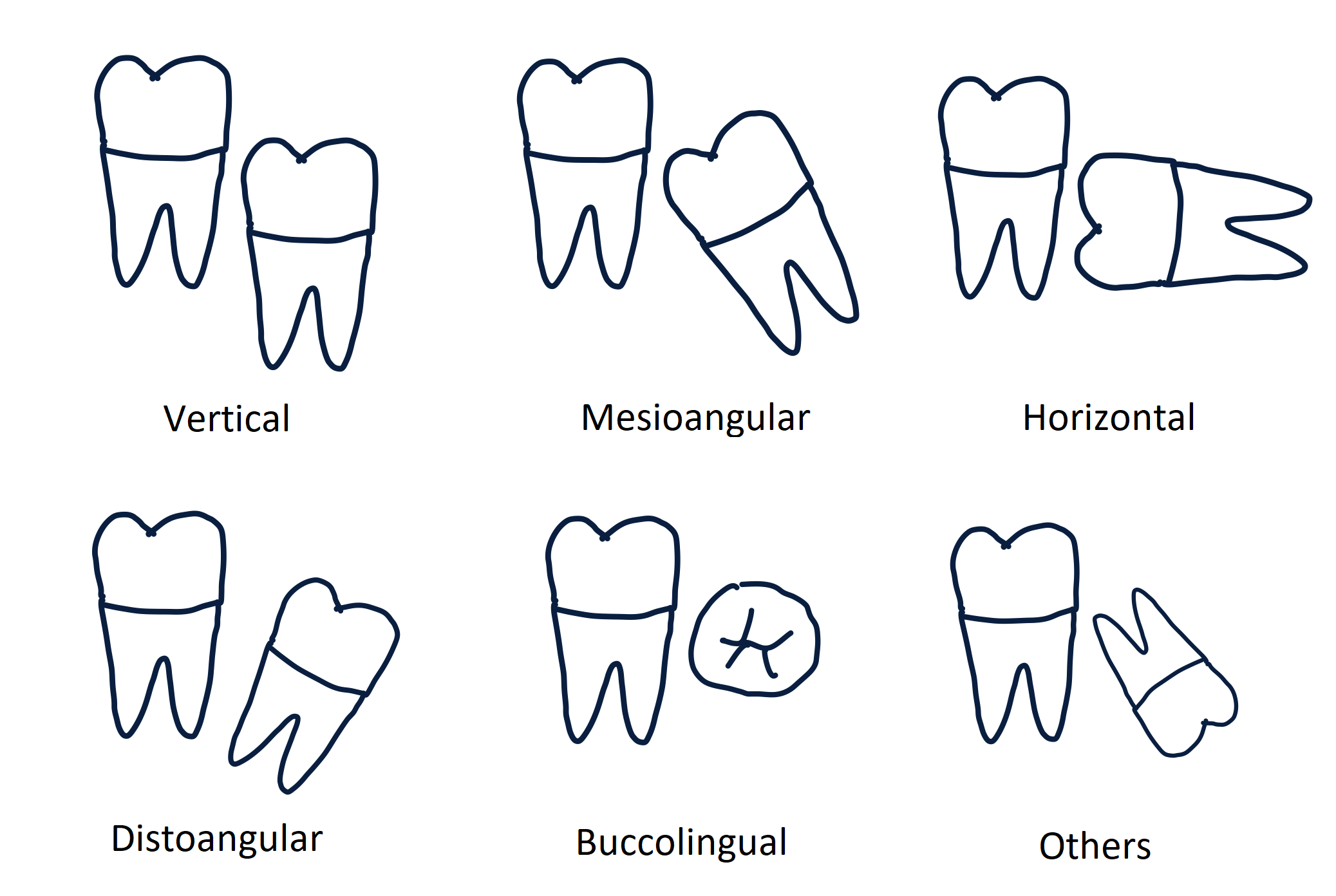

As pericoronitis is primarily associated with mandibular third molar eruptions, the incidence of the disease varies depending on the third molar eruption pathways or positions. Mandibular third molar eruption positions can be described by two classifications: Pell and Gregory classification and Winter’s classification (see Images. Pell and Gregory Classification and Winter Classification of Third Molar Angulation). Studies have shown that vertically positioned third molars are most commonly associated with pericoronitis compared to other positions, while horizontal positioning had decreased occurrences of pericoronitis. Also, teeth with Pell and Gregory classification A had a greater prevalence of pericoronitis than those with B classification. However, there was no significant difference in prevalence between Pell and Gregory classes I and II.[2]

Systemic factors can promote or exacerbate the presentation of pericoronitis. Patients with impaired immune systems, such as those with uncontrolled diabetes or immunodeficiency disorders, can be more prone to developing pericoronitis. Also, pericoronitis can be triggered or worsened by other systemic conditions that can temporarily compromise the immune response. These include mental or physical stress, upper respiratory infection, or menstruation for females.[3]

Epidemiology

There is a limited number of studies on the prevalence of pericoronitis, and the results vary among studies. Incidence from a study of a military population showed a 4.92% prevalence among patients who are between 20 and 25 years old. Statistically, 95% of the infections were associated with mandibular third molars.[4] As pericoronitis is mostly associated with erupting third molars, the condition is most commonly seen in people aged 20 to 29 years when the eruption of third molars tends to occur.[5] There seems to be no sex predilection for pericoronitis.

History and Physical

Pericoronitis symptoms usually begin locally in the posterior mandible, near erupting third molars. Patients initially report localized pain and swelling at the back of the mouth that can change to radiating pain to the surrounding structures. The symptoms usually worsen with function and over time.[6] It can also present with an unpleasant taste, halitosis, purulent discharge, limited mouth opening, and difficulty swallowing in more advanced stages. These symptoms can decrease the quality of daily life by disturbing activities such as speaking, mouth opening, chewing, and sleeping.[7] Also, dysphasia, trismus, and extraoral swelling may indicate the spread of infection to adjacent deep spaces of the head and neck, potentially compromising the airway.

It is also important to note that patient presentation may differ based on whether patients have chronic or acute pericoronitis. Acute pericoronitis is characterized by the sudden onset of more severe signs and symptoms of inflammation in the affected intraoral region. Chronic pericoronitis presents with a long history of milder symptoms.[6]

Evaluation

Intraoral physical examination of patients with pericoronitis can show localized erythema, edema, purulence, and tenderness to palpation in the posterior mandible, where third molars are erupting. More advanced stages of pericoronitis, lymphadenopathy, fever, facial asymmetry, limited mouth opening, difficulty swallowing, change of voice, or even difficulties breathing can be noticed. Prompt intervention is necessary with the latter symptoms as they may indicate pending airway obstruction.

Pericoronitis can be divided into transient or non-transient based on the position of the erupting tooth that is associated with the condition.[6] If a tooth is erupting into a favorable, cleansable, and functional position, the inflammation of the soft tissue, or pericoronitis, will resolve as the operculum over the tooth regresses. However, if the tooth cannot erupt into a favorable position, the infected operculum may persist over the unfavorably erupted tooth, causing non-transient pericoronitis.

Radiographic examination is an important aid in diagnosing pericoronitis as it can show the positions of erupting third molars if present. A panoramic radiograph is the best method to assess the presence and the position of erupting third molars. Pell and Gregory's classification and Winters's classification can be used to describe the position of third molars. Studies have shown that vertical positioning of third molars is associated with a higher prevalence of pericoronitis, as discussed in the etiology section.[2] However, when evaluating pericoronitis, dental professionals need to consider all affecting factors like oral hygiene, the position of the opposing dentition, and the length and severity of clinical presentations.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for pericoronitis can differ among dental professionals depending on their experience, clinical skills, and clinical settings. There are a variety of treatment options to manage pericoronitis. Unfortunately, there is a lack of a consistent treatment algorithm for pericoronitis. Early recognition and initiating treatment to resolve signs and symptoms of pericoronitis is key to the successful management of pericoronitis. This resource should provide available treatment options that dental professionals can use according to their clinical judgment.

Non-surgical Treatment Options

Local debridement/Oral Hygiene: Local intervention to remove the impacted debris and decrease the bacterial load is the recommended first-line therapy for patients presenting with mildly symptomatic pericoronitis with a low concern of systemic infection. Sterile solutions (normal saline, water, chlorhexidine, hydrogen peroxide) can be used to irrigate the pericoronal space. Mechanical debridement using periodontal instruments can also help further clean the infected pericoronal pocket.[6] Maintaining good oral hygiene to prevent further buildup is important in treating and preventing pericoronitis.[8]

Pain management: Pain can greatly limit chewing and taking in good oral intake for patients with pericoronitis. Pain management, in addition to resolving infection, is crucial in pericoronitis management. There are multiple modalities for pain management: local anesthetic injections, topical analgesics, and oral analgesics. Oral analgesia with NSAID should be the primary method of pain management.[9]

Systemic antibiotics: Antibiotics are indicated for pericoronitis when the systemic spread of infection is suspected. Amoxicillin (500 mg orally every 8 hours for five days) or metronidazole (400 mg orally every 8 hours for five days) are recommended for organisms causing pericoronitis. For patients who are allergic to penicillin, erythromycin can be considered. Microbial cultures can help guide antimicrobial selections.

Surgical Treatment Options

Soft tissue surgery: Removing the infected soft tissue can help resolve pericoronitis as it is the soft tissue disease overlying an erupting third molar. The operculum, soft tissue covering erupting third molar, can be removed to eliminate the deep pocket formed between the gingiva and the tooth. This surgery is also known as operculectomy, and laser, electrocautery, radiofrequency ablation, or scalpel can be used. Removal of the soft tissue covering the third molar can also help with the tooth eruption.[10] This treatment option is limited to third molars with a favorable eruption position. For example, if a tooth is erupting vertically with adequate space from the distal aspect to the tooth to the anterior border of the ramus, operculectomy can help resolve pericoronitis. However, if a tooth is horizontally impacted or there is inadequate space for eruption, the areas that are hard to clean will likely persist, which may cause pericoronitis to recur.

Pericoronal ostectomy: If a tooth is in a favorable position to erupt into functional occlusion with adequate space, removing the bone that is covering the coronal portion of the erupting tooth can help accelerate the eruption.[11]

Extractions: Tooth extraction is an irreversible procedure. Dental providers should consider other treatment options and compare the risks and benefits before determining whether a tooth should be removed or not. Also, a referral to a specialist may be needed depending on the clinician’s experience or available surgical equipment. If, after close examination and assessment, a tooth is deemed not likely to erupt into functional occlusion and has an increased risk of persistent infection, extraction of the tooth or the opposing tooth can be considered.

Extraction of the opposing tooth: If there is an opposing tooth that is exacerbating pericoronitis by causing mechanical trauma, extraction of the opposing tooth may be considered to help address pericoronitis. Removing the source of mechanical insult can significantly reduce the symptoms of pericoronitis. Nevertheless, this treatment option may be a temporary solution when immediate extraction of the involved mandibular third molar is not feasible. It can be used to decrease the severity of pericoronitis with a plan to extract mandibular third molar extraction at a later date.

Extraction of the involved tooth: Extraction of a tooth is the most permanent solution to pericoronitis when the tooth does not have a favorable eruption position. For example, if a tooth is horizontally impacted, it is not possible to completely irrigate and debride the infected pericoronal space. The inferior portion of the pericoronal space created by the impacted tooth will not be cleaned, and bacteria will continue to proliferate, increasing the risk of chronic pericoronitis that could lead to a more severe infection. Removing the third molar will resolve pericoronitis by removing the unreachable, uncleansable space. Historically, there have been debates on whether extraction of a tooth involved with acute infection would increase the risk of deep space infection. Studies show that extractions should not be delayed when indicated. Early extraction with appropriate adjunct treatments, such as systemic antibiotics and drainage of purulence, expedite the recovery and minimize the risk of infection spreading.[12]

Depending on how patients present and the dental provider’s assessment, different combinations of the therapies mentioned above can be used to treat and prevent pericoronitis.

Differential Diagnosis

Pericoronitis is diagnosed clinically with the presence of soft tissue inflammation and infection. When assessing for pericoronitis, it is also important to consider other conditions that can present with similar signs and symptoms. The following conditions may co-exist with pericoronitis or could be considered for differential diagnosis. Radiographic examinations or histological studies can help differentiate one condition from another.

- Foreign body impaction

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Peripheral ossifying fibroma

- Dental caries

- Periodontitis

- Periapical abscess or granuloma

Prognosis

The amount of dental plaque is positively associated with pericoronitis.[8] If the third molars have adequate space to erupt into a cleansable position, pericoronitis may resolve once the eruption is complete. However, pericoronitis may persist or recur if a tooth is unlikely to erupt into a favorable position. For such symptomatic pericoronitis, removal of the third molars significantly improves the symptoms and quality of life.[13] Also, extractions of symptomatic third molars are shown to improve the periodontal status of the adjacent second molars.[14]

Complications

Pericoronitis, when untreated, can lead to the spreading of the localized infection to the nearby head and neck spaces: sublingual, submandibular, parapharyngeal, pterygomandibular, infratemporal, submasseteric, buccal spaces.[15] Such space infections should be recognized early, as delayed treatment can put a patient at increased risk of life-threatening airway compromise.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As pericoronitis results from an overgrowth of bacteria in the hard-to-clean areas that form during third molar eruptions, good oral hygiene is crucial in preventing pericoronitis or worsening the disease.[8] Proper teeth brushing, flossing, and use of mouth rinse can decrease the bacterial load at the eruption site. It is also possible that some areas cannot be reached or cleaned during daily oral hygiene. This is why patient education is important to allow patients to recognize the signs and symptoms of pericoronitis and seek dental care. Detecting pericoronitis at an earlier stage can help patients encounter fewer symptoms, earlier recovery, and decrease the risk of developing more severe infections.

Another way to deter developing pericoronitis is to remove a future source of infection. If upon radiographic examination, a patient’s third molar has a poor prognosis to erupt into functional occlusion, which increases the likelihood of developing pericoronitis, it is fair to consider prophylactic third molar extractions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pericoronitis is a localized dental infection. Recognition of clinical presentation of the condition and referral to a dental provider who can diagnose and treat the disease would be crucial in improving patient outcomes.