Continuing Education Activity

Odontogenic cysts are frequently identified on routine examinations with head and neck imaging such as orthopantomograms and computed tomography (CT). Clinicians must obtain a complete medical history and perform a thorough head and neck exam on all patients. In evaluating odontogenic cysts, the clinical examination and interpretation of radiographic studies are essential phases; however, tooth vitality testing is equally important. Tooth vitality testing is required in formulating an appropriate differential diagnosis for odontogenic cysts. This step is essential in determining treatment and ultimately guides patient outcomes. This activity reviews the most common odontogenic cysts, etiologies, appropriate therapies and highlights the role of the healthcare team in evaluating, managing, and treating patients with these entities.

Objectives:

Describe the clinical and radiographic presentation of common odontogenic cysts.

Review the potential etiologies of the most common odontogenic cysts.

Identify methods to differentiate the most common odontogenic cysts from one another and formulate appropriate differential diagnoses of radiolucency lesions on a radiographic exam.

Summarize the appropriate treatment modalities for the most common odontogenic cysts.

Introduction

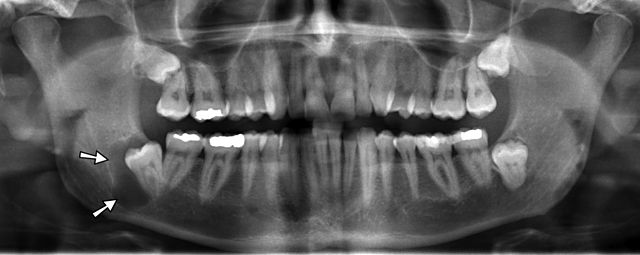

Odontogenic cysts are usually identified on routine exams and are generally classified as inflammatory or developmental. Radiographically, they present as a unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion with distinct borders; however, they cannot be differentiated radiographically. In addition, odontogenic cysts may share similar radiographic appearances with aggressive odontogenic tumors (see Image. Radiograph, Odontogenic Cyst in the Right Mandible).

Inflammatory odontogenic cysts are classified as:[1][2]

- Periapical cyst

- Residual cyst

- Paradental cyst

Developmental odontogenic cysts are classified as:[1]

- Dentigerous cyst

- Eruption cyst

- Lateral periodontal cyst

- Gingival cyst

- Odontogenic keratocyst (OKC)

- Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cyst

- Glandular odontogenic cyst

Etiology

A cyst is an epithelial-lined cavity. The epithelial lining of odontogenic cysts arises from the odontogenic epithelium, which includes reduced enamel epithelium (REE), the epithelial cell rest of Serres, and the epithelial cell rest of Malassez (ERM).[1] The REE is the epithelium that surrounds the developing crown of the tooth. The rests of the Serres are remnants of the degeneration of the dental lamina, which is responsible for initiating tooth formation during the sixth week of embryonic life. The ERM is residual cells from the disintegration of Hertwig’s epithelial root sheath, which initiates root formation. Ultimately, these rests become entrapped within the maxillary and mandibular gingiva and the alveolar bone.[2]

Periapical cysts are inflammatory and are the most common odontogenic cysts. They develop at the root apex of a non-vital tooth due to inflammation caused by dental caries or trauma.[3] This inflammation causes the activation and proliferation of the ERM, located around the apex of the affected tooth. As a result, there is an increase in osmotic pressure, which causes expansion of the cyst. Frequently, the ERM is not activated, and only granulation tissue develops at the apex of the affected tooth. This granulation tissue is termed a periapical granuloma and, as such, histologically lacks an epithelial lining. Some have considered the periapical granuloma a precursor of the periapical cyst.[2]

Residual cysts are very similar to periapical cysts as they both have an inflammatory etiology. Residual cysts are a result of inadequate removal of the periapical cyst at the time of extraction. Microscopically, residual cysts are identical to periapical cysts.[1][2]

Paradental cysts are odontogenic cysts with an inflammatory etiology. Depending on the tooth and the location, they may be given such terms as a buccal bifurcation cyst or mandibular infected buccal cyst. These cysts occur at the crown or root of a partially or fully erupted tooth. They are located on the buccal, mesial, or distal aspects of the tooth. Paradental cysts result from inflammation of the junctional epithelium within the gingival sulcus of an erupting or erupted tooth. The associated tooth frequently has a buccal enamel extension, which is generally the initiator of an inflammatory reaction.[2][4][2]

Dentigerous cysts are developmental in origin. They occur when fluid accumulates between the tooth crown and enamel epithelium, dilating the tooth follicle. Consequently, this ultimately prevents the tooth from erupting.

Eruption cysts are developmental cysts and are considered the soft tissue variant of the dentigerous cyst. They are caused by a lack of separation of the dental follicle from an erupting tooth.

Lateral periodontal cysts are developmental cysts that arise from the rest of the Serres.[2]

Odontogenic keratocysts (OKC) have a developmental etiology and arise from the rest of the Serres.[2]

Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts have a developmental etiology and arise from the rest of the Serres.[2]

Glandular odontogenic cysts have a developmental etiology and arise from the rest of Serres or ERM.

Epidemiology

Epidemiological information regarding odontogenic cysts is as follows:

- Periapical cysts are the most commonly reported odontogenic cysts. Per Johnson et al., periapical cysts comprise approximately 60% of all odontogenic cysts. They are more commonly found in the maxilla about 60% of the time.[3]

- Residual cysts comprise approximately 5% of all odontogenic cysts.[3][4]

- Paradental cysts comprise 3 to 5% of all odontogenic cysts.[5]

- Dentigerous cysts, Per Johnson et al., comprise 20.6% of all odontogenic cysts. It counts for 20% of all mandibular cysts.[4][1]

- Eruption cysts occur primarily in young children during the eruption of their deciduous or permanent teeth.

- Lateral periodontal cysts account for less than 3% of all odontogenic cysts. Approximately 70% occur in the mandibular canine to premolar regions, while they occur less commonly in the canine-lateral area in the maxilla.[6]

- Odontogenic keratocysts, per Johnson et al., represent 4 to 12% of all odontogenic cysts. They occur more frequently in the second and third decades of life.[4]

- Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts are the most uncommon of all the odontogenic cysts, and they occur typically in males in their 40s.

- Glandular odontogenic cysts are rare, accounting for less than 0.2% of all odontogenic cysts.[3]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of odontogenic cysts depends on the type of cyst.

- Periapical cysts occur through an inflammatory process from non-vital teeth. Apical inflammation occurs due to a bacterial infection and/or pulpal necrosis and will form granulation tissue. The inflamed granulation tissue causes increased osmotic pressure that leads to the proliferation of the residual rest of Malassezia.[1][2]

- Residual cysts are remnants of periapical cysts. They occur due to incomplete removal of periapical cysts during a previous tooth extraction.

- Paradental cysts are inflammatory in origin and arise from the junctional epithelium of the gingival sulcus or at the cementoenamel junction of the lateral erupted side of the tooth, often near the root furcation.[5]

- Dentigerous cysts are developmental in origin and associated with an impacted tooth, which has failed to erupt. A dentigerous cyst develops as fluid accumulates between the enamel epithelium and dental enamel; the fluid dilates the dental follicles and ultimately prevents eruption.[7]

- Eruption cysts are developmental in origin and occur due to the buildup of blood or fluid within expanding dental follicular space. The space develops due to the separation of dental follicles from the enamel of the erupting tooth.[8]

- Lateral periodontal cysts are developmental in origin and arise from rests of the dental lamina at the lateral aspect of the root surface.[6]

- Odontogenic keratocysts are developmental in origin and arise from the rests of the dental lamina.[2]

- Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts are developmental in origin and arise from the rests of the dental lamina.[2]

- Glandular odontogenic cysts are developmental in origin.[9]

Histopathology

Periapical Cyst

Histologically, a periapical cyst has one to two thin cell layers of nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium associated with inflamed fibrous connective tissue and inflammatory infiltrates. The luminal epithelium will appear “looped and arcaded” due to the inflammatory hyperplasia.

Residual Cyst

Residual cysts are histologically identical to periapical cysts.[2]

Paradental Cyst

Histologically, the paradental cysts are indistinguishable from periapical cysts; however, they are located pericoronally instead of periapically.[5]

Dentigerous Cyst

Histologically, dentigerous cysts have nonkeratinized-stratified squamous epithelium with sometimes elongated interconnecting rete ridges. Dentigerous cysts can also demonstrate mucous, ciliated, and sometimes sebaceous cells.[7]

Eruption Cyst

Histologically, an eruption cyst is similar to a dentigerous cyst.[8]

Lateral Periodontal Cyst

Histologically, lateral periodontal cysts have three to eight cell layers of nonkeratinized squamous or cuboidal luminal epithelium that often contains some focal thickening (swirls) with clear cells, which contain glycogen.[2][6]

Odontogenic Keratocyst

Histologically, odontogenic keratocysts (OKC) have six to ten cell layers stratified squamous epithelium with a distinct wavy or corrugated parakeratinized layer. The basal cells are cuboidal to columnar and are palisaded and hyperchromatic.[10]

Orthokeratinizing Odontogenic Cyst

Histologically, orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts have a varied thickness of orthokeratinized-stratified squamous epithelium. The cyst lacks the palisaded or hyperchromatic basal layer.[11]

Glandular Odontogenic Cyst

Histologically, glandular odontogenic cysts show varied thicknesses of squamous epithelium lined with hobnail cells or surface eosinophilic cuboidal cells. Commonly, epithelial spheres or plaque-like thickenings are observed within the cyst wall. Glandular odontogenic cysts often contain mucus goblet cells, respiratory epithelium, or duct-like structures.[2][9]

History and Physical

Periapical cysts are typically not seen clinically; however, they are suspected in the presence of teeth with large carious lesions or that have been traumatized. A periapical cyst is a radiographic finding. It often presents as a unilocular lesion with a well-demarcated border, measuring less than 10 mm in greatest diameter, and located at the root apex of the tooth.[12]

Residual cysts cannot be seen clinically and radiographically; they are similar in appearance to a periapical cyst. However, they are associated with a previously extracted tooth.

Paradental cysts occur primarily in young patients associated most commonly with an erupting or erupted first mandibular molar. They present with gingival edema, purulent discharge, and deep pockets on probing.[5][13]

Dentigerous cysts are associated with the erupting or impacted tooth. There is a greater incidence of occurrence in the first and second decade of life, with the third molars and maxillary canines most affected. The cysts are asymptomatic unless they become inflamed.[7]

Eruption cysts occur in young children or infants during the eruption of either the deciduous or the permanent teeth. They present as alveolar edema with a blueish hue.

Lateral periodontal cysts (LPC) may result in displacement of the roots interproximally. Unlike other odontogenic cysts, LPCs occur later in life, often in the 40s and 50s, and have a male predilection.[1]

Odontogenic keratocysts are typically asymptomatic; however, they may present with intra-oral edema, pain, trismus, neurosensory deficits, and infection. Because they expand anteriorly-posteriorly within the alveolar bone, they are difficult to appreciate clinically. The mean age distribution is 20 years.[14][10]

Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts are very similar to OKCs clinically; however, they have a much better prognosis. There is a male predilection, and the age ranges from 20 to 40 years old.[1] Generally, they are associated with an impacted tooth.

Glandular odontogenic cysts are aggressive and are predominately a radiographic finding. Clinically, however, there may be an increase in tooth mobility and cortical perforation observed. The mean age of presentation is 46 years and with a slight male predominance.[9]

Evaluation

Periapical Cyst

Periapical cysts are inflammatory cysts. Clinically, the involved tooth is non-vital due to either a history of or extensive dental caries and/or trauma. Radiographically, periapical cysts present as a unilocular radiolucency at the apex of the tooth demonstrating well-defined borders, which may be corticated.[12]

Residual Cyst

Clinically, the patient is partially edentulous, as the offending tooth was previously extracted. Residual cysts are similar in radiographic appearance to periapical cysts; however, they are not associated with a tooth. Consequently, it is essential to inquire about the patient's previous dental history.

Paradental Cyst

Detailed clinical and radiographic evaluations are critical in identifying these cysts. They are associated most often with an erupted mandibular first molar or partially impacted mandibular third molar. Clinically, erythema, edema of the marginal gingival tissue, prudence discharge, and a deep probing depth are noted. The patient may have a history of pericoronitis. Radiographically, they present as a pericoronal, well-demarcated unilocular radiolucency at the tooth's buccal, mesial, or distal aspects.[5][13]

Dentigerous Cyst

Dentigerous cysts are commonly associated with an impacted tooth (eruption delay or partially erupted). It is essential to obtain radiographs to evaluate. Clinically, a dentigerous cyst is asymptomatic unless it is inflamed. Radiographically, dentigerous cysts appear as well-demarcated, unilocular radiolucency located at the cementoenamel junction of the tooth. They may appear radiographically similar to an OKC or ameloblastoma.[1][2] It has been theorized that radiolucencies exceeding 4 mm indicate more aggressive behavior, in which tooth displacement can occur.

Eruption Cyst

Eruption cysts are diagnosed clinically; however, they should be confirmed with radiographic imaging. Examination will determine whether the cyst causing the delayed eruption is associated with a deciduous or permanent tooth. The overlying gingival tissue has edema, a bluish hue, and/or a translucent appearance.[8] Eruption cysts are the gingival counterpart of the LPC.

Lateral Periodontal Cyst (LPC)

Clinically, involved teeth are vital and may appear to be displaced or demonstrate associated mobility. They may also present with alveolar expansion—buccally or lingually. The interproximal gingival mass is immovable and firm, without erythema or signs of infection. Similar to other odontogenic cysts, LPCs are commonly an incidental radiographic finding and are usually painless. Radiographically, they are a well-demarcated unilocular radiolucency located interproximally between two adjacent roots. A variant of LPC, the botryoid (grape-like) odontogenic cyst, presents in the same location; however, it appears as a multilocular/multicystic radiolucency.[6]

Odontogenic Keratocyst

Approximately 25 to 40% of odontogenic keratocysts are associated with an impacted tooth.[10]. Clinically, the patient may have delayed tooth eruption, and thus it is important to obtain diagnostic radiographs to evaluate. OKCs are frequently asymptomatic as they expand in an anterior-posterior direction with little to no buccolingual expansion. Larger OKCs may present with pain, intraoral edema, trismus, sensory deficits, infection, and drainage. Radiographically, OKCs have varied presentations ranging from a well-demarcated unilocular lesion with smooth borders to a unilocular lesion with a scalloped border to a multilocular radiolucency.[2] Patients presenting with multiple OKC lesions should be evaluated for or referred to evaluate for nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Gorlin syndrome is an autosomal dominant inherited condition resulting from mutations in the PTCH tumor suppressor gene mapped to chromosome 9q22. The syndrome is significant for multiple basal cell carcinomas, palmar pits, multiple OKCs, and bilamellar calcification of the falx cerebri. Genetic testing of the patient and close family members are required to make an official diagnosis of Gorlin syndrome.[1][2]

Orthokeratinizing Odontogenic Cyst

Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cyst should not be mistaken for a variant of OKC. It is commonly associated with an impacted tooth, and thus clinically, a patient may experience delayed tooth eruption. It is important to obtain radiographs to evaluate impacted teeth. Radiographically, orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts present as a well-demarcated unilocular radiolucency usually seen in the posterior mandible region.[2]

Glandular Odontogenic Cyst

Clinically, erupted teeth in association with glandular odontogenic cysts are often associated may have mobility or displacement. Additionally, there may also be swelling, alveolar expansion, pain, or neurosensory deficit. Radiographically, GOCs may present as a unilocular or multilocular radiolucency with well-demarcated borders crossing the midline. They are aggressive, usually resulting in root displacement and resorption.[9]

Treatment / Management

Periapical cysts are commonly treated with non-surgical endodontic (root canal) therapy. If the tooth remains symptomatic after endodontic therapy, surgical endodontic therapy or extraction will be required. Surgical endodontic therapy, apicoectomy (removing the root apex), and curettage of the cyst produces reliable bone healing. Extraction with curettage or enucleation of the socket is also effective at eliminating the occurrence of a residual cyst. Overall, surgical endodontic therapy results in 95% bone healing compared to 66% bone healing with non-surgical treatment.[15]

Treatment for residual cysts is enucleation.

Treatment for paradental cysts depends on the location of the cyst and its associated tooth. If associated with a first or second molar, the cyst is typically enucleated and allowed to heal. If associated with a third molar, extraction is the treatment of choice.

Treatment for dentigerous cysts is the extraction of the associated tooth followed by curettage and enucleation.[1]

Eruption cysts are self-limiting and therefore do not require treatment. The cyst will typically rupture on its own as the tooth erupts. If symptomatic, the cyst can be unroofed to reduce any associated inflammatory pressure.[8]

Lateral periodontal cysts are treated with curative enucleation. Curettage in conjunction with enucleation is often necessary for botryoid odontogenic cysts.[6]

Odontogenic keratocysts are treated with various modalities, depending on the size and location of the lesion. Smaller OKCs are manageable by enucleation and possible peripheral ostectomy to achieve healthy bony margins. Larger OKCs may require marsupialization or a resection. With a high recurrence rate, patients are clinical and radiographic followed-up.[14]

Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts are treated with surgical excision, which is curative. Unlike OKCs, they have a low recurrence rate.

Glandular odontogenic cysts are treated with enucleation and curettage. Some of the more extensive cases may require resection. Regardless of the treatment option, close follow-up is needed.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

Periapical Cyst

- Periapical granuloma

- Early stages of Periapical cementoosseous dysplasia

- Periapical scar

Residual Cyst

- Unicystic ameloblastoma odontogenic keratocyst

- Glandular odontogenic keratocyst

- Lateral periodontal cyst

Paradental Cyst

- Periapical cyst

- Dentigerous cyst

- Residual cyst

- Lateral radicular cyst

Dentigerous Cyst

- Hyperplastic dental follicles

- OKC

- Ameloblastoma

Eruption Cyst

- Epstein pearls

- Bohn nodules

- Gingival cyst

Lateral Periodontal Cyst

- OKC

- Glandular odontogenic cyst

- Gingival Cyst

Odontogenic Keratocyst

- Ameloblastoma

- Dentigerous cyst

- Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cyst

Orthokeratinizing Odontogenic Cyst

- Dentigerous cyst

- OKC

- Ameloblastoma

Glandular Odontogenic Cyst

- OKC

- Dentigerous cyst

- Botryoid cyst

Prognosis

Periapical cysts generally have a good prognosis following treatment. Prognostic variables include but are not limited to the tooth affected, the size of the cyst, and the extent to which the bone is damaged.[2]

Residual cysts have an excellent prognosis and should not recur if adequately treated.

Paradental cysts have an excellent prognosis with no reports of recurrence.[13]

Dentigerous cysts have an excellent prognosis if treated appropriately. Their recurrence rate is relatively low; however, without complete enucleation or curettage at the time of the extraction, they can recur.[7]

Eruption cysts have a good prognosis. They are commonly self-limiting, as the erupting tooth often ruptures the cyst.

Lateral periodontal cysts have a good prognosis with a meager recurrence rate.[6]

Odontogenic keratocysts have a favorable to fair prognosis. Their recurrence may range from 20-62%, depending on the type of treatment rendered. With aggressive treatment options, such as resection, recurrences have not been reported.[10] Enucleation has a reported recurrence rate as high as 56%. Regardless of the treatment option, close clinical and radiographic follow-up is recommended.[11][16]

Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts have a good prognosis with a reported recurrence rate as low as 2%.[11]

Glandular odontogenic cysts have a favorable to fair prognosis with a relatively high recurrence rate of 20 to 30%. The potential for multiple recurrences is high; therefore, close long-term follow-up is recommended.[9]

Complications

Complications associated with odontogenic cysts are also contingent on the precise type of cyst:

- Periapical cysts do not typically present with complications after excision. A residual cyst may form due to incomplete curettage during extraction and a periapical scar may develop when a lesion fills with collagenous tissue rather than bone.[16]

- Residual cysts can cause bone destruction if left untreated, which puts the adjacent teeth at risk. In general, these cysts do not present with complications once removed and have a low to no recurrence after excision.

- Paradental cysts are associated with pericoronitis, which is a deep periodontal pocket. This may damage to the local periodontium as a consequence of the follicular expansion. Typically, they do not present with complications once removed and they do not recur after excision.[5]

- Dentigerous cysts are associated with bony destruction due to the expansion of the cyst.[5] Typically do not present with complications once removed and there is low to no recurrence after excision.[7]

- Eruption cysts are often self-limiting and present without complications.[8]

- Lateral periodontal cysts typically do not present with complications once removed and they do not recur after excision.

- Odontogenic keratocysts have a high recurrence rate; therefore, close follow-up is necessary. If recurrence occurs, the patient will require additional surgical treatment.

- Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts have a low recurrence rate and do not present with complications once removed. They do not recur after excision.

- Glandular odontogenic cysts have a high recurrence rate (20 to 30%); consequently, close interval and long-term follow-up is necessary. The potential for multiple recurrences is high.[2][9] If there is a recurrence, the patient will require additional surgical treatment.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Periapical cysts are inflammatory in nature. Patients must practice good oral hygiene and seek routine and preventive dental care. It is essential to discuss clinical and radiographic findings with patients and offer treatment options. Lastly, the provider should counsel the patient on outcomes for any lesions identified. Patients will better understand, especially if they are unresponsive to the initial treatment.

Residual cysts are inflammatory and occur after incomplete surgical treatment. Routine dental visits are key to early diagnosis. In addition, patients should be made aware of any radiographic findings and counseled on lesion biopsy to rule out other lesions.

Paradental cysts are inflammatory in nature. Therefore, patients need to practice good oral hygiene and seek routine dental care, including a radiographic examination.

Dentigerous cysts are developmental in origin. The provider should discuss the findings and offer a differential diagnosis to the patient. Treatment options should include conservative management, such as extracting impacted teeth with biopsy to rule out other lesions. The surgical removal of these lesions typically results in complete resolution.

Eruption cysts are developmental in origin, often self-limiting, and usually present with no complications. Patients should be informed and reassured that the lesions will most likely self-resolve with the eruption of the underlying tooth.

Lateral periodontal cysts are developmental in origin. Therefore, patients should be made aware of these lesions and plan to have them excised. Conservative management and subsequent removal of these lesions classically result in resolution.

Odontogenic keratocysts are developmental in origin. Patients should be made aware of these lesions and plan to have them excised. Conservative management and subsequent removal of these lesions usually result in their resolution. However, patients should schedule a close and long-term clinical and radiographic follow-up due to the high recurrence rate.

Orthokeratinizing odontogenic cysts are developmental in origin. Patients should be made aware of these lesions and plan to have them excised. Conservative management and subsequent removal of these lesions normally result in permanent resolution.

Glandular odontogenic cysts are developmental in origin. Patients should be made aware of these lesions and counseled on the general statistics and outcomes. Treatment options must be thoroughly discussed, and the patient is given the opportunity to ask questions. However, due to its high recurrence, close clinical and radiographic follow-up is required.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Odontogenic cysts can be inflammatory or developmental in nature. Good oral hygiene and routine dental care can reduce the likelihood of inflammatory odontogenic cysts. In addition, routine clinical and radiographic examinations can aid in detecting asymptomatic inflammatory and developmental odontogenic cysts.

Treatment of these lesions can range from monitoring to surgical treatment. Lesions that have rapid growth, are fixed, and/or appear atypical should be referred immediately to the appropriate healthcare specialist for evaluation, biopsy, diagnosis, and management.

Most members of the healthcare team will encounter odontogenic cysts in their practice. The majority of the cysts are developmental in nature and possess low malignant potential. It is important to note, routine and preventive dental care can reduce extensive treatment and result in more favorable outcomes.