Continuing Education Activity

Microphthalmia with cyst is a common, complicated, congenital anomaly whose management is extremely challenging. To avoid significant morbidity and to attain satisfactory outcomes, it must be thoroughly evaluated and appropriately managed. This activity reviews the evaluation, treatment, and rehabilitation and highlights the interprofessional team's role in effectively managing the patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the etiological factors contributing to microphthalmia with the cyst.

- Outline the clinical presentation and the systemic associations of this disorder.

- Summarize the step-by-step approach to management in microphthalmia with the cyst.

- Explain the importance of close monitoring and follow-up in these patients.

Introduction

Microphthalmia is one of the most common congenital ocular malformations, characterized by a small yet identifiable eye and its elements.[1] This contrasts with anophthalmia, which is defined as the complete absence of the eye due to deficient development or arrest of differentiation during earlier stages of development. Congenital microphthalmia with cyst is a rare developmental sub-type of microphthalmia and must always be differentiated from a congenital cystic eye, also known as anophthalmia with cyst.[2] Microphthalmia with cyst is a debilitating congenital anomaly whose management must be initiated as soon as possible for satisfactory outcomes.

Etiology

The basis of the development of microphthalmia with cyst is embryological. Normally, the embryonic fissure's closure begins at the 11 mm stage and completes by the 18 mm embryonal stage. The invagination of the optic vesicle begins prior to the 6-7th embryological week. Following this, differential growth of the inner layer of the optic cup occurs (where the inner layer develops faster than the outer layer), resulting in everted margins of the fissure.

The complete formation of the retina at these margins may prevent the closure of the optic cup. In the case where the closure fails, a typical coloboma is formed. When no closure occurs, these retinal layers further distend, followed by accumulation of fluid in between the layers, leading to the formation of a cyst.[3] The gradual accumulation of fluid in the cystic cavity may be attributed to the presence of microvilli in the inner layer of the cyst comprising the glial tissue. Another postulated theory is the presence of a communication between subarachnoid space and the cyst, which may result in enlargement of the cyst. The extensive, non-neoplastic, reactive proliferation of the glial tissue may further lead to cavity expansion.[4][5]

It is the timing of the developmental arrest that plays a key role in understanding this entity's etiology. Microphthalmia with cyst results when the embryological disturbances occur later at the 7 to 14 mm stage during 6 to 7 weeks of gestation, a time when ocular structures are already present. On the contrary, when the arrest occurs during the 2 to 7 mm stage, causing failure of invagination of the primary optic vesicle, anophthalmos with cyst results.[6]

The influence of gestational insult on the development of microphthalmia with cyst is controversial. Recognition of the related genetic syndromes with appropriate genetic counseling must be done. Although most cases present in isolation, familial occurrence in monozygous twins and in siblings, has been documented.[7]

Epidemiology

Although the prevalence of microphthalmia varies between 1.4 to 3.5 per 10,000 births, there is a paucity of literature regarding the demographic profile of microphthalmia with cyst. Few studies have reported a prevalence as low as 0.3 to 0.6 per 10,000 births.[8][7]

Microphthalmia with cyst is a non-hereditary disorder without any gender predilection. It generally appears within the first few months after birth and may be detected as early as the neonatal period. Although the majority of the cases are unilateral, microphthalmia with a cyst can manifest bilaterally.[1]

Histopathology

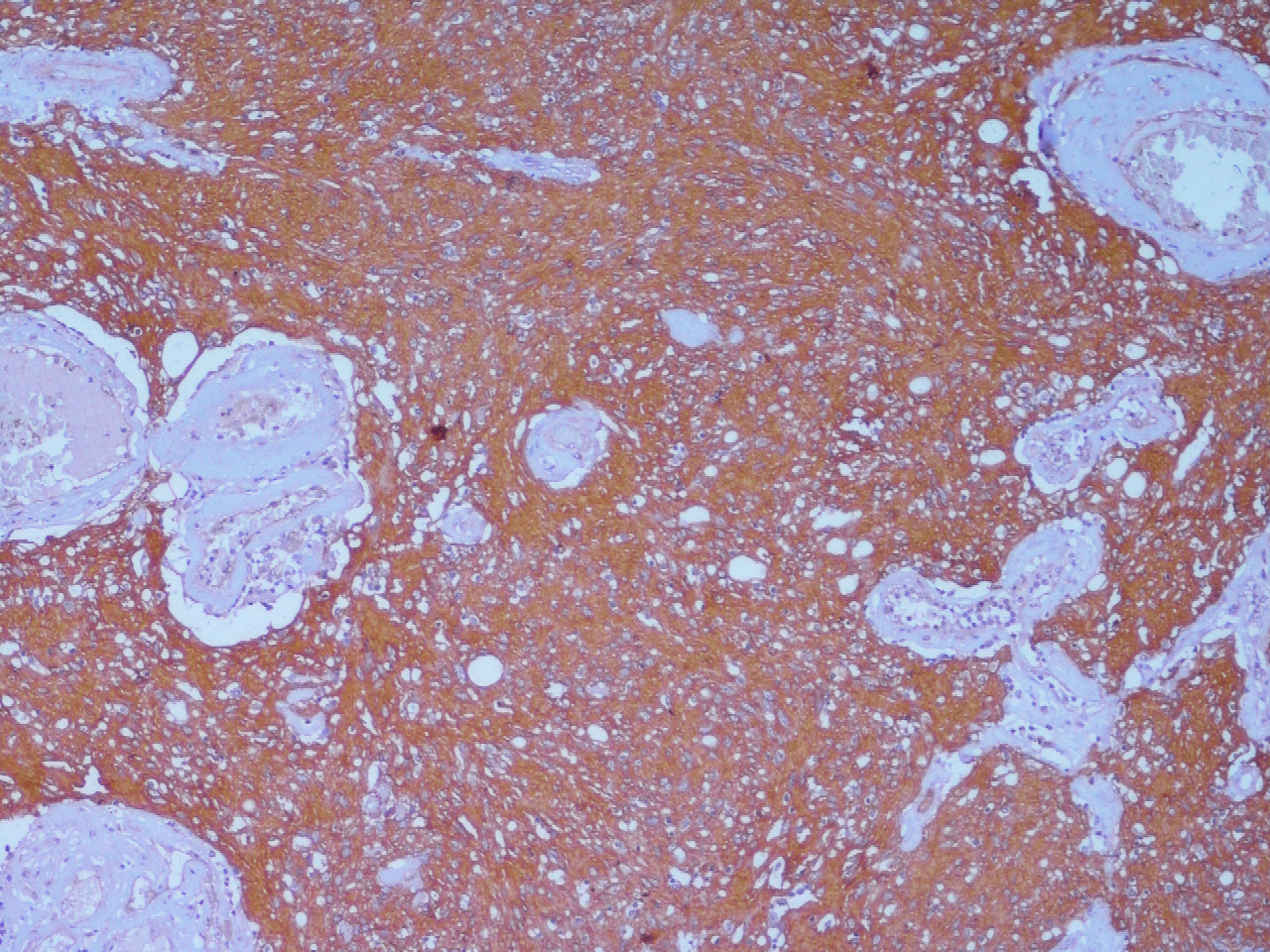

Histopathology with immunohistochemistry (IHC) remains the gold standard investigation for confirming the diagnosis of microphthalmia with the cyst.

The outer wall of the cyst is composed of dense fibrous connective tissue and the inner layer, derived from the neuroectoderm, comprises thick neuroglial tissue with variably differentiated immature retinal elements seen in relation to the glial element. A varying amount of calcification and pigmentation may be found in the cystic cavity. Surrounding rudimentary ocular structures may be seen in connection with the cyst.[3]

The cyst is usually found attached to the inferior portion of the globe in microphthalmos, unlike anophthalmia, where the cyst is usually centrally or superiorly located with the absence of ocular structures. IHC may reveal glial positivity, owing to the expression of astrocytes, using glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) staining. Optic nerve elements are identified using the neurofilament protein, and the surrounding meningeal tissue may demonstrate epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) positivity. Disorganized retinal tissue may stain positive for S-100, vimentin, and neuron-specific enolase (NSE).[2]

Recent advances in IHC, scanning, and transmission microscopy have aided in gaining further insights into these complex malformations.

History and Physical

The majority of the patients encountered in the ophthalmic setting present with visual impairment since birth, bulging of the lower lid (may rarely involve the upper lid), firm bluish swelling (sometimes seen through the conjunctiva) with positive transillumination, orbital mass, forward protrusion of the globe, or an inability to open the eye since birth.[9] Irido-fundal coloboma, optic disc coloboma, cloudy cornea, microcornea, shallow anterior chamber, angle-closure glaucoma, or pupillary membrane are the reported associations of the microphthalmic globe.[10] It is essential to evaluate the status of the contralateral eye in unilateral cases to exclude an underlying pathological condition.[11]

It is important to look for other systemic abnormalities such as microcephalus, cardiac conduction defects, basal encephalocele, cleft lip, corpus callosal agenesis, saddle nose, pulmonary hypoplasia, renal agenesis, and mid-brain deformities in a case of microphthalmia with cyst, especially if the disorder is bilateral.[6]

Evaluation

Clinically, microphthalmia with cyst is classified into three types (Duke-Elder classification).[7]

- Type 1 = Relatively normal eye with a clinically inapparent cyst

- Type 2 = Grossly deformed eye with an obvious cyst

- Type 3 = Large cyst which has pushed the globe backward, rendering it clinically invisible

Although the diagnosis of microphthalmia with cyst is mainly derived clinically, the role of orbital imaging can’t be overemphasized. Standardized Ultrasonography (USG A + B-scan) is the preferred initial investigation modality as it is rapid, non-invasive, easily accessible, and helps in determining the status of the eye (whether anophthalmic or microphthalmic). Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) aids in identifying associated neurological abnormalities and can be safely used in children. It may also detect communication channels between the globe and the cyst. Diffusion-weighted MRI and the Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC), in cases of rapidly enlarging cystic mass, may assist in differentiating it from a malignancy. Computed Tomography (CT) scan is better for delineating osseous structures and is especially useful for surgical planning in hypoplastic orbits. CT-based three-dimensional reconstruction is currently being utilized for presurgical planning. However, CT should be used cautiously in children due to a 0.1% risk of radiation malignancies.[12] Radiologically, the microphthalmic globe can be divided into mild (17-21mm), moderate (12-16mm), and severe (<12mm). Similarly, the orbital cyst can also be classified as small (<10mm), moderate (>10mm to 20mm), and large (>20mm).[9]

Once the diagnosis is established by corroborating clinico-radiological and histopathological findings, the next step is to assess the visual potential of the eye. It has been shown that around 80% of cases of microphthalmia with corneal diameter 5mm or less have no perception of light.[13] Electrodiagnostic tests such as Visual Evoked Potential may be useful in cases of doubtful visual potential. Associated systemic abnormalities must be evaluated and addressed accordingly, along with a pediatric review.

Treatment / Management

There is a lack of availability of concrete guidelines on the management of microphthalmia with cyst. The basic approach towards managing this condition is determined by certain critical factors. Prime consideration should be given to

- Age at presentation

- Volume of the orbit

- Pattern of the growth of the cyst.

Visual and cosmetic rehabilitation should be initiated only after ensuring no visual potential in the microphthalmic globe.

Orbital volume in a normal person linearly expands up to 5 to 6 years of age, followed by a marked decrease in the rate in the subsequent years.[14] The presence of a cyst in a microphthalmia eye, as a matter of fact, may contribute to the orbital expansion of the affected eye, thereby minimizing the inter-orbital asymmetry.[15] Hence, careful consideration should be given prior to surgically intervening in a child < 7 years of age.

The indications of early cyst removal are as follows:[16]

- Ill-fitting prosthesis or orbital wall displacement in the presence of the cyst

- Rapidly progressive cystic enlargement due to spontaneous or post-traumatic hemorrhage into the cavity. A dark red fluid (instead of the usual translucent yellow fluid) is revealed on examination in these cases.

- Cyst prolapse through the palpebral fissures

In a child < 7 years of age, conformer therapy must be initiated as soon as the patient’s first presentation in the clinics for best outcomes. For the first few months, a weekly follow-up is usually recommended. Serial augmentation of the conformer’s size with successive visits is necessary as the child grows. Customized, painted, or centrally hollow (when the vision is preserved) conformers are being worn lately. If the orbital volume is severely reduced (< 85% as compared to the contralateral side), the use of orbital expanders over rigid conformers is the preferred approach.[12]

Socket enlargement is directly proportional to the implanted volume in the socket. As compared to the rigid, static spheric implants made from silicone, orbital expanders (dynamic orbital implants) increase in volume to stimulate bony orbital growth in these hypoplastic juvenile sockets. An autogenous Dermis Fat Graft (DFG), a natural biocompatible, slow-growing dynamic implant, is an effective option for socket reconstruction in a hypoplastic orbit.

Synthetic orbital expanders are of three types:[17]

- Hard spherical implants – Patients with these implants often require subsequent surgeries, thereby undergoing repeated ocular trauma

- Inflatable soft tissue expanders – Saline-filled fluid chambers are fixed to the subperiosteal orbital space, and the filling port is attached subcutaneously in the temporalis fossa. Disadvantages include premature extrusion, uncontrolled directional expansion, and a painful injection.[18][19]

- Hydrogel implants[20] – These solid hydrophilic expanders are made of methyl methacrylate and N-vinylpyrrolidone and have a propensity to expand up to 30 times their original volume when hydrated. Although an appealing alternative, cessation of expansion on reaching the equilibrium and its long-term fragility are a matter of concern. These implants are available in spheric, hemispheric, and pellet forms.[11][21]

Approved by United States Food and Drug Administration (US-FDA) in 2006, integrated tissue expander fulfills all basic criteria for an ideal expander with minimal tissue loss and subsequent surgical procedures. Since it is inserted through a lateral canthal incision, simultaneous placement of prosthesis may be performed over an intact conjunctival surface.

Surgically excising the cyst (in-toto) is the recommended method of removal. Cyst aspiration may be performed prior to surgical removal or as a stand-alone procedure. A high recurrence rate limits its use as the first line of surgical treatment.[9][7] Few authors have advocated the use of concurrent sclerotherapy, using ethanolamine oleate, to enhance resolution rates.[22][23] Although a more comfortable approach, evidence regarding the use of sclerosants in microphthalmia with cyst is scarce, and the potential fibro-inflammatory response may render the subsequent surgery extremely challenging.

In a severely microphthalmic globe (with no visual potential) with an associated cyst, excision may be combined with enucleation/evisceration followed by placement of an orbital implant (DFGs, hydroxyapatite, Medpor – porous polyethylene, or silicone) in the same setting.

Any eyelid procedure or socket reconstruction using mucous membrane grafts should be reserved for the late phase of life. In patients with Blepharophimosis and increased inter-canthal distance (ICD), a combined Z lateral canthoplasty and V-Y medial canthoplasty is an effective method of correction. A secondary surgery in the earlier stage of life leads to cicatrix formation resulting in poorer cosmesis. A customized prosthesis must be considered for better outcomes.[15]

Orbito-cranial advancement surgery that allows for the advancement of bone forwards and outwards by virtue of bone grafts should be kept as a last resort in hypoplastic orbits.[24]

Differential Diagnosis

Congenital cystic eye, also known as anophthalmia with cyst, is a close differential diagnosis of microphthalmia with the cyst. Both the conditions may present with a clinically invisible globe. Therefore, appropriate investigations, as discussed above, must be performed to identify the presence of any ocular elements.[25] Unlike the cyst associated with microphthalmia, the cyst related to the congenital cystic eye has a predilection towards the upper and central part of the orbit. On histopathology, unlike microphthalmia, no rudimentary ocular structures are seen.

A sudden onset, rapidly progressive orbital mass may raise a suspicion of malignancy. Conditions such as a dermoid cyst, epidermoid cyst, arachnoid cyst, meningocele, orbital teratoma, primary optic nerve sheath cysts, and encephalocele may mimic the intra-orbital cyst associated with microphthalmia.[3] A meticulous evaluation with a dedicated work-up is of paramount importance in all these cases.

Prognosis

Microphthalmia with cyst itself is associated with a poorer prognosis in comparison to other types of microphthalmia. The various prognosticating factors associated with an unfavorable prognosis include:

- Absence of visual potential confirmed on electrodiagnostic tests

- Severe disease

- Poor orbital volume

- Late age at presentation

- Avoidable cyst excision in < 7 years of age. Unless indicated, a cyst in a child of < 7 years should be left untouched owing to its contribution to orbital growth.

- Early lid surgery and socket reconstruction (pre-pubertal)

- Enucleation/Evisceration without orbital implants

- Discontinuation of expanders in early childhood/ Refusal to maintain the prosthesis

- Inability to maintain socket and prosthetic hygiene

- Infrequent follow-up visits

Complications

Cosmetic disfigurement and absent visual potential are a few of the most worrisome complications of this complex disorder.

Surgery-related complications include bleeding, secondary infections, extensive cicatrix formation post-operatively, contracted socket, recurrence, and orbital hematoma.[9]

Graft-related complications include fat atrophy and necrosis in the case of DFGs. It is worth noting that the incidence of atrophy of fat is rare in the pediatric age group, making it a viable alternative for volume replacement.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Microphthalmia with cyst is a challenging entity, where patient as well parent education plays a significant role in dealing with its aesthetic, functional, and psychosocial ramifications. Maintenance and disciplined use of conformer therapy and orbital expanders should be encouraged. Proper counseling to help the family understand precisely the prognosis of the condition should be done. The value of a regular follow-up with the surgeon, the ocularist, and the rehabilitation team, should be explained to the patient and his/her family. Even with minimal visual potential, cosmetic and visual rehabilitation is of prime importance in achieving significantly better outcomes.

Pearls and Other Issues

Microphthalmia with cyst is a congenital malformation and hence, cannot be prevented. However, the associated cosmetic and functional disability can be minimized if appropriate measures are taken at every step. As opposed to the loss of an eye in adulthood, an early loss in childhood results in hypoplasia and volume loss of the affected orbit. It leads to distorted orbital-facial growth, rendering the management more challenging. Hence, an early presentation and a timely intervention are recommended to effectively manage these patients. Another issue is the loss of follow-up and the unwillingness of the parents to place a conformer/orbital expanders/prosthesis in the child’s orbit. The importance of close monitoring of the orbital growth and volume, and the need for these therapeutic measures to minimize asymmetry and achieve desirable aesthetic and functional outcomes, should be well-explained.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multi-disciplinary approach involving a co-ordinated team of an ophthalmologist, ocularist, pediatrician, and the patient’s family, is vital to enhance the outcomes. This inter-professional approach also aids in lowering the health-related financial burden on the patient’s family and promotes better compliance to treatment. Addressing psychosocial issues, connecting with the patient’s family, setting up futuristic goals and endpoints, and awareness regarding important time frames in a child’s life will maximize the outcomes.