Technique or Treatment

Images are obtained using the often large anterior fontanelle as an ultrasonic window to the brain. Anterior fontanelle closes between 9 months to 15 months of age. It typically allows reliable brain imaging for at least the first 6 months of life. Images are obtained in coronal and sagittal planes. Coronal images are obtained by angling the transducer from anterior to posterior. Six standard planes are suggested. A sagittal midline image is first obtained. The transducer is then angled from midline to the right and midline to the left to obtain parasagittal images of the cerebral hemispheres. Any skull opening can be used, including metopic suture and posterior fontanelle.

Images of the posterior fossa are obtained using the mastoid fontanelle. The mastoid fontanelle is located at the junction of squamosal, lambdoid, and occipital sutures and can remain open until 2 years of age. The transducer is placed 1 cm above the tragus and 1 cm behind the helix.[1] It is useful for assessing posterior fossa structures such as cerebellar hemispheres, cerebellar vermis, 4th ventricle, cisterna magna, and occipital horns of the lateral ventricles. Posterior fontanelle views are useful for evaluating atria and occipital horns of lateral ventricles through the posterior fontanelle located above the external occipital protuberance. Posterior fontanelle closes at about 3 months of age.

Sonographic Anatomy

Coronal planes: Six standard coronal planes are obtained through (1) frontal horns of lateral ventricles anterior to foramen of Monro, (2) foramen of Monro, (3) posterior aspect of the third ventricle through the thalami, (4) quadrigeminal cistern, (5) trigones of lateral ventricles, (6) parietal and occipital cortex. Genu of the corpus callosum is seen anterior and superior to frontal horns of lateral ventricles. Cavum septum pellucidum is seen as an anechoic area inferior to the corpus callosum and extends posteriorly to the fornices as cavum verge. Sylvian fissures at the periphery of cerebral hemispheres are seen as echogenic Y-shaped structures.[2] In healthy full-term neonates, white matter is slightly more echogenic than cortical gray matter.[3]

Sagittal planes: Sagittal planes are obtained through (1) midline, (2) caudothalamic groove on each side, (3) body of each lateral ventricle, and (4) each cerebral cortex through Sylvian fissure. On midline sagittal view, corpus callosum, pericallosal sulcus containing pericallosal artery, cingulate gyrus, cavum septum pellucidum, cavum vergae, 3rd, and 4th ventricles, choroid plexus in the roof of the third ventricle, cerebellar vermis, cisterna magna, and brainstem are seen. Parasagittal images show the caudothalamic groove as a thin echogenic line with a caudate nucleus anteriorly and thalamus posteriorly. The body of the lateral ventricle is seen with choroid plexus along its floor. Further lateral image shows frontal horn, body, temporal and occipital horns of the lateral ventricle. The glomus of the choroid plexus is seen within the ventricular trigone. Surrounding cerebral hemisphere and periventricular halo posterior to the occipital horns are seen.

Intracranial Hemorrhage

The germinal matrix is an area of neuronal and glial proliferation, is highly vascular, and contains fragile single-cell thick vessels.[2] It is a common site of hemorrhage in premature low-birth-weight infants with an incidence of 20 to 25%. The absence of autoregulation and cardiovascular instability resulting in blood pressure fluctuation is the major risk factor for germinal matrix hemorrhage (GMH).[4] Most GMH occurs within the first few days of life, with 80 to 90% in the first 3 or 4 days of life. Papile classification is widely used for grading intracranial hemorrhage in premature infants. According to this classification, intracranial hemorrhage is divided into 4 grades:

- Grade 1, subependymal hemorrhage only

- Grade 2, subependymal hemorrhage with extension into normal-sized ventricles

- Grade 3, subependymal hemorrhage with extension into dilated ventricles

- Grade 4, subependymal hemorrhage with extension into dilated ventricles and associated intraparenchymal hemorrhage/venous infarction

In the US, grade 1 hemorrhage is seen as an echogenic mass in the caudothalamic groove. With time, the area of hemorrhage undergoes central liquefaction and becomes echopenic, and may develop subependymal cysts. Grade 2 hemorrhage is seen as a focus of increased echogenicity in the ventricles or fluid level in the dependent occipital horns of the lateral ventricles. Color Doppler can be used to separate avascular clots from the choroid plexus, which is has contained vessels. Grade 3 hemorrhage is seen as echogenic blood in dilated lateral ventricle/ventricles. As with any intraventricular hemorrhage, the echogenicity within the periventricular cerebral parenchyma is due to white matter venous infarction, most commonly involving frontal and parietal lobes. With time the white matter infarction liquefies and will appear echoless. At times a porencephaly is seen. Post hemorrhagic hydrocephalus develops in more than two-thirds of cases. Cerebellar hemorrhage is underdiagnosed and noted in 10% to 25% of very low birth weight infants at autopsy.[2]

Mastoid views have helped its diagnosis, especially for the cerebellar hemisphere closest to the transducer. Like all intraparenchymal hemorrhages, the hemorrhage appears homogenously hyperechoic, then heterogeneous, and eventually hypoechoic with time.

Subdural hemorrhage is seen as linear or elliptical extra-axial fluid collection causing mass effect on the underlying brain parenchyma. Widening of the interhemispheric fissure may be seen. Infratentorial subdural hemorrhage is seen as a fluid collection between tentorium and cerebellar hemispheres. A high-frequency linear transducer helps diagnose subarachnoid and subdural hemorrhage due to its great near-field resolution. Such transducers can also help diagnoses sinus thrombosis, which is sometimes seen as a complication of neonatal dehydration.

Hypoxic-ischemic Injury(HII)

The pattern of injury in both preterm and term infants depends on the severity and duration of the injury. Brain circulation in premature infants is different from term infants resulting in different patterns of injury.

HII in premature neonates: HII is more common in premature neonates due to lack of autoregulation.[1] Before 32 weeks of gestation, blood vessels from the pial surface penetrate and supply the cerebrum resulting in poor supply to the periventricular white matter and making it more prone to ischemic injury.[5] Mild to moderate hypotension results in injury to the periventricular white matter resulting in periventricular leucomalacia. Severe hypoxia affects the areas of advanced myelination such as globus pallidus, thalami, dorsal brain stem, hippocampus, and cerebellum.[1][5]

The perirolandic cortex is spared as it myelinates later, after 35 weeks of gestation. Early changes of cerebral edema and hypoxia are seen as the accentuation of gray-white matter differentiation. With increasing severity, diffuse or patchy areas of hyperechogenicity, slit-like ventricles, effacement of cerebral sulci, and interhemispheric fissure are seen.

HII in term neonate: In cases of mild to moderate hypotension, blood is shunted to the posterior circulation, and the brain stem, cerebellum, and basal ganglia are spared. Ischemic changes are seen in the watershed distribution between anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries.[5]

Severe hypoxia results in deep gray matter and brain stem injury and affects the ventrolateral thalami, posterior putamina, dorsal brainstem, corticospinal tracts, perirolandic cortex, and hippocampus. In the US, areas affected by hypoxic-ischemic injury appear hyperechoic with loss of distinction between the central gray nuclei and surrounding white matter. Peripherally reversal of cortical gray and white matter echogenicity is seen with gray matter more hyperechoic than subcortical white matter when cortical necrosis develops. Cerebral edema associated with HIE manifests as effacement of extra-axial fluid spaces and slit-like ventricles.[6]

Despite what can be seen by the US in cases of HII, it is MR, particularly with DWI sequences, that is the best tool for HII analysis. However, sick neonates may not be able to undergo the trip to an MR nor the long times for MRI examinations.

Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL): PVL refers to the infarction of periventricular white matter in watershed areas of the brain, often best seen just lateral to the frontal horns and in the white matter superior and lateral to the ventricles. The peritrigonal white matter is another area of potential PVL but often is echogenic based on anisotropy as the US beam through the anterior fontanelle crosses the white matter at a 90-degree angle, enhancing its echogenicity and potentially simulating echogenic PVL. PVL results in auditory, visual, and motor deficits and spastic diplegia or quadriplegia, findings associated with the broad term cerebral palsy.

In echogenic PVL, the US shows areas of increased echogenicity in periventricular white matter predominantly in the peritrigonal areas within 2 weeks of insult.[1] In cases of PVL, the peritrigonal echogenicity is more than that of the choroid plexus differentiating it from normal peritrigonal flare. Echogenic areas, if not asymmetrical, may appear normal. If concerned, a 2 to 3-week follow-up in the US will show affected areas as cystic. If not picked up, however, those areas will fill in with scar tissue and appear unremarkable on the US. In such cases, it is only the evidence of white matter volume loss, e.g.ventriculomegaly or widening of cerebral sulci and the interhemispheric fissure, that can suggest abnormality occurred. Timing of follow-up exams is important.

Congenital Malformations

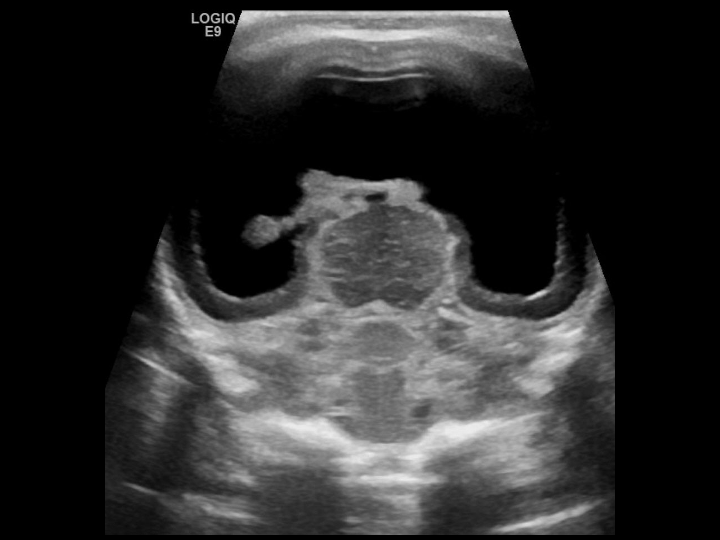

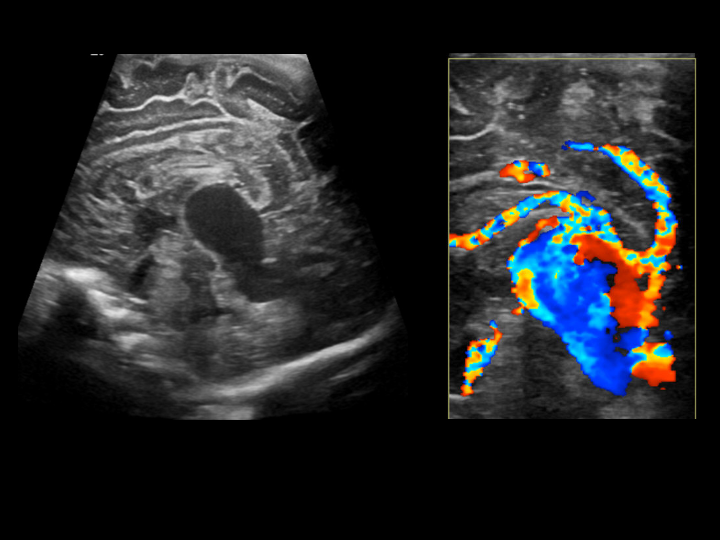

Vein of Galen malformation: Vein of Galen malformation (an arteriovenous malformation (AVM)) occurs as a result of the failure of regression of primitive median prosencephalic vein of Markowski and its replacement by internal cerebral veins. The resultant AVM is due to a fistulous connection between cerebral arteries and this primitive vein. There are two types of vein of Galen malformations, choroidal( 90%) and mural. The AVM of the more common choroidal type is one where numerous arteries connect with the dilated prosencephalic vein. Neonates present early due to high output cardiac failure and intracranial bruit.

The US shows an anechoic, pulsatile, vascular mass in the midline posterior to the third ventricle. The aneurysmally dilated vein drains into a dilated straight sinus that drains into the sagittal sinus to transverse/sigmoid sinus and into the internal jugular veins, all of which are usually dilated. Spectral Doppler shows elevated velocities with dampened pulsatility in the feeding arteries and arterialization of the draining veins. Mural type AVMs present later in infancy due to hydrocephalus or seizures and are due to a direct arteriovenous fistula.[7]

Chiari malformation: Three types of Chiari malformation are described. Type I, Type II, Type III. Type II is most common in childhood and is found in almost 100% of patients with myelomeningocele. The US shows an enlarged Massa intermedia, pointing of the anterior aspects of the lateral ventricles, nonspecific colpocephaly (occipital horns of lateral ventricles are larger than the normal-sized frontal horns). There may be a partial or total absence of corpus callosum, but most importantly for the diagnosis is a small posterior fossa and non-visualization of the cisterna magna due to its effacement by the downward displacement of the infratentorial contents into the upper cervical spine. The downwardly pulled cerebellar hemispheres become banana in shape rather than maintaining a normal peanut shape, and there is a small or absent 4th ventricle.[2]

Type I Chiari malformation refers to a caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils below the foramen magnum. Type III is characterized by caudal displacement of the medulla and 4th ventricle with associated occipital or high cervical encephalocele containing dysplastic cerebellar tissue.

Anomalies of the corpus callosum: The corpus callosum (CC) is a midline commissure formed in the 3rd to 4th month of life that connects the two cerebral hemispheres. The corpus callosum consists of four parts that form anterior to posterior: the rostrum, genu, body, and splenium, except for the rostrum, which forms last. Corpus callosum may be completely absent (agenesis) or hypoplastic. Agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC) can occur as an isolated abnormality or associated with congenital syndromes.[8]

In ACC, coronal US images show the absence of the corpus callosum as widely separated frontal horns of the lateral ventricles, which in combination with a high riding third ventricle (no longer in its lower position because of the absent CC) suggests an image of and hence the named "Texas longhorn" and "Viking helmet" signs. Other sonographic findings include parallel orientation of the lateral ventricles, colpocephaly (non-specific dilation of posterior body and occipital horns of lateral ventricles), and the presence of tubular soft tissue densities, Probst bundles, that parallel each other and are seen indenting along the medial wall of the frontal horns of lateral ventricles. These bundles represent the white matter commissure that never developed to cross midline as the CC. A dorsal midline cyst may be seen.

Dandy-Walker complex and other posterior fossa cystic malformations: The Dandy-Walker complex consists of the Dandy-Walker malformation and the Dandy-Walker variants/spectrum (e.g., mega cisterna magan or vermian-cerebellar hypoplasia). Classic Dandy-Walker malformation (DWM) is characterized by an enlarged 4th ventricle communicating with the cisterna magna through space normally occupied by a cerebellar vermis. There is an enlargement of the posterior fossa and superior displacement of torcula herophili and tentorium cerebelli. The cisterna magna is enlarged at >10mm. Associated hydrocephalus is seen in up to 80% of the cases. The Dandy-Walker spectrum includes mega cisterna magna with enlargement of the cisterna magna but no vermian abnormality. The posterior fossa may be normal or only mildly enlarged. Cerebellar hemispheres may be normal or slightly small. The vermis may be hypoplastic but not absent.

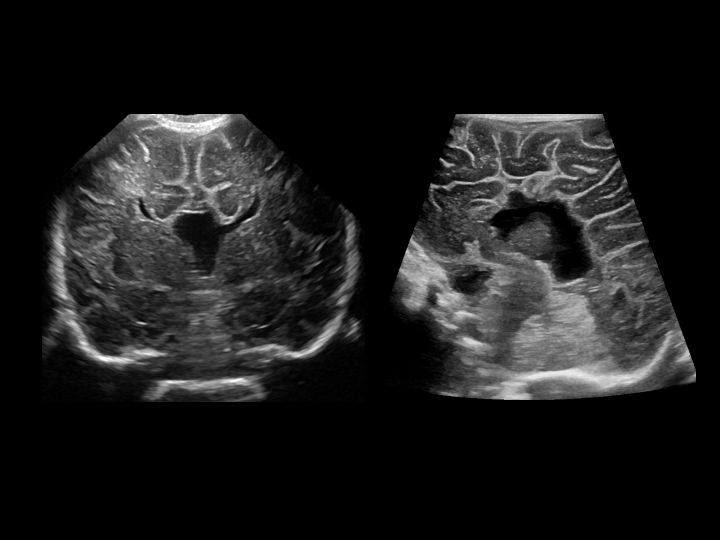

Holoprosencephaly: Holoprosencephaly (HPE) results from failure of cleavage of the prosencephalon into telencephalon and diencephalon at 5 weeks of gestation.[9] HPE is a spectrum of malformations with very variable clinical manifestations. It is usually associated with midline facial anomalies such as cleft lip and palate and cyclopia ("the face predicts the brain").[9] It is classically divided into three subtypes, alobar, semilobar, and lobar types.

Another entity, the midline interhemispheric variant (MIH), also called syntelencephaly, is also included in the spectrum of HPE. MIH consists of midline interhemispheric fusion. Alobar is the most severe form with complete fusion of the cerebral hemispheres and thalami and a single horseshoe-shaped midline ventricle. Corpus callosum, falx, third ventricle, and intrahemispheric and Sylvian fissures are absent. In semi lobar type, cerebral hemispheres are fused anteriorly, and thalami are partially separated. Single frontal horn and body of the lateral ventricles with rudimentary occipital and temporal horns of lateral ventricles are seen.

Posterior falx and interhemispheric fissure are partially developed, and splenium of the corpus callosum may be present. In the lobar type, cerebral hemispheres are almost completely separated except most anterior parts of the frontal lobes. Frontal horns of lateral ventricles are fused, bodies of lateral ventricles are separate but closely opposed, and occipital and temporal horns are separate. Corpus callosum may be present with only the anterior body and genu absent or hypoplastic.

Schizencephaly: Schizencephaly is a rare congenital anomaly, and most cases are sporadic. It is categorized as a disorder of neuronal migration and is divided into open-lip and closed-lip schizencephaly. A new classification system has been proposed, in which schizencephaly is divided into 3 types. Type 1 schizencephaly- trans-mantle column of abnormal grey matter but no evidence of a CSF-containing cleft on MR imaging, type 2 schizencephaly-CSF-containing cleft present, abutting lining lips of abnormal grey matter opposed; and type 3 schizencephaly-CSF-containing cleft present, non-abutting lining lips of abnormal grey matter.[10]

Gray matter-lined cleft extends ependymal to the pial surface, that is, from the lateral wall of the lateral ventricle to the cerebral cortex. Open lip schizencephaly is characterized by a wide cleft that is easily identified in the US. Closed lip schizencephaly can be difficult to identify with the US, but the diagnosis may be suggested by nipple-like outpouching from the lateral wall of the ventricles.

Congenital infections: Congenital viral infections are commonly known by the acronym TORCH and include Toxoplasma gondii, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes, and others. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common congenital infection and is seen in 1% of live births. Symptoms include microcephaly, neonatal seizures, hepatosplenomegaly, and petechial rash.[11] On head US, periventricular calcifications, periventricular or gelatinolytic cysts, temporal and occipital lobe cysts, and lenticulostriate vasculopathy (calcification of thalamostriate vessels) can be seen. MRI shows migrational anomalies such as polymicrogyria (PMG) and lissencephaly and cerebellar hypoplasia. Toxoplasmosis can cause calcifications in the basal ganglia, thalami, cerebral cortex, and periventricular white matter. Neonatal herpes occurs during transvaginal delivery from infection of the birth canal and manifests as meningoencephalitis, parenchymal necrosis, and encephalomalacia.

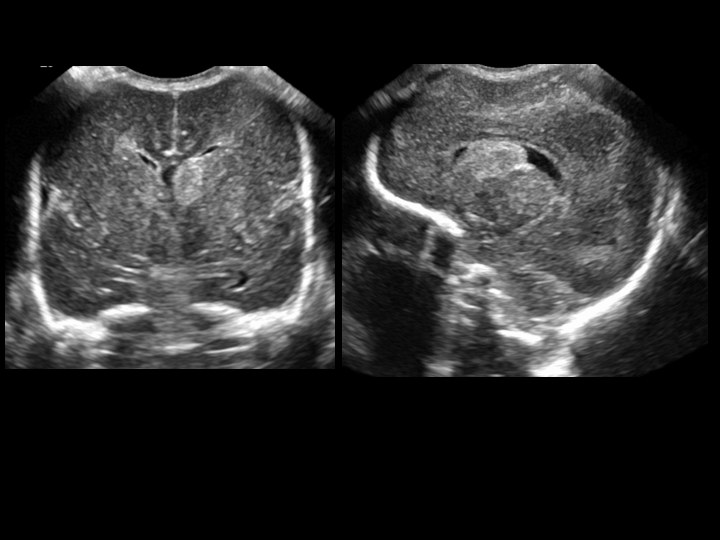

Ventriculomegaly/Hydrocephalus: Dilatation of the ventricles (ventriculomegaly) is called hydrocephalus when associated with increased intraventricular pressure. It can be obstructive, occurring due to obstruction of CSF outflow or impaired absorption of CSF by arachnoid villi or non-obstructive resulting from overproduction of CSF due to choroid plexus papilloma. Obstructive hydrocephalus can be communicating (extraventricular obstruction to CSF flow in subarachnoid space or impaired absorption by arachnoid villi)) or non-communicating (intraventricular obstruction to CSF flow). Congenital causes include aqueductal stenosis, Chiari II malformation, a vein of Galen malformation, Dandy-Walker malformation. The most common hereditary cause of hydrocephalus is X-linked hydrocephalus associated with aqueductal stenosis and occurs as a result of L1CAM mutation. Acquired causes in infants include hemorrhage (most common), infection (usually bacterial meningitis), and tumors.[12]

US shows an enlargement of the ventricles, which could involve all the ventricles when the obstruction is extraventricular or when there is overproduction of CSF. Isolated ventricular dilatation can be seen when the obstruction is intraventricular. Other findings include parenchymal thinning and fenestration of the septi pellucidi, which can simulate the absence of the septi pellicidi (DiMorsier syndrome)

Arachnoid cyst: Arachnoid cyst is seen as an avascular anechoic, well-defined mass and may cause mass effect on the subjacent brain and midline shift. Differential includes cisterna magna and cavum septum pellucidum, and vergae, which do not produce the mass effect in contrast to the arachnoid cyst.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): ECMO can be a life-saving procedure in infants with cardiac and respiratory failure. Intracranial hemorrhage (because patients are placed on anticoagulants) and thromboembolism are potential complications of ECMO. According to the extracorporeal life support organization(ELSO), head ultrasound should be performed every 24 hours for 5 days in stable patients. In patients who are hemodynamically unstable or have unstable coagulation profiles, HUS should be performed daily until the patient is stabilized.[13] HUS should be performed if there is a significant clinical status change. As mentioned earlier, hemorrhage and infarct may have a similar appearance.