Continuing Education Activity

A transvaginal ultrasound offers an invaluable avenue for imaging the female pelvic anatomy. It augments transabdominal ultrasound for a more complete evaluation of the ovaries, adnexa, uterus, cervix, and surrounding pelvic regions. Typically, an ultrasound technician will conduct the scanning and take images of the normal structures, with more dedicated images or cine clips obtained of aberrant anatomy, pathologic processes, or pregnancy. The images are read by a radiologist, guiding the treatment by an interprofessional team.

Objectives:

Determine the purpose of the transvaginal ultrasound.

Identify how to perform the endovaginal ultrasound.

Apply the utilities and limitations of the transvaginal ultrasound.

Communicate the basics of interpreting an endovaginal ultrasound by an interprofessional team.

Introduction

Transvaginal ultrasound imaging is unique in its ability to closely visualize the female reproductive organs that would otherwise be difficult to see on transabdominal ultrasound. Additionally, unlike computer tomography (CT), this is a more up-close imaging modality without the utilization of ionizing radiation. There are many indications for this, both diagnostic and interventional. An ultrasound technician first conducts a transabdominal scan for a thorough exam and follows it with a transvaginal ultrasonographic exam. Images are uploaded to a picture archiving and communication system or PACS system for the radiologist to interpret. Adnexal/ovarian masses and cysts, endometrial pathologies, fibroids, and pregnancy (ectopic and intrauterine), as well as evaluation of developmental anomalies, are a non-exhaustive list of indications that are commonly evaluated with this imaging modality (See Image. Transvaginal Ultrasound).

Anatomy and Physiology

The ability to properly evaluate the female pelvis sonographically requires proficiency in anatomy. An ultrasonographer positions the probe so that a marker propagating on every image consistently indicates the cephalad on sagittal imaging and the right side on transverse imaging. Beginning externally, the introitus gives way to the vaginal canal, which ends at the cervix. The cervix has 2 portions: the ectocervix, which protrudes out into the vagina, and the supravaginal portion, which connects with the uterus.[1]

The endocervical canal connects the vagina and uterine cavity. Circumferentially to the cervix, the fornices are invaginations of the distal vaginal mucosa. A transvaginal ultrasound probe may be placed anteriorly, posteriorly, or on either side of the cervix by placement within the fornix. The posterior fornix creates the inferior border of the Pouch of Douglas, while the anterior fornix borders the vesicouterine pouch inferiorly.

The external os of the cervix gives rise to the endocervical canal and terminates at the internal cervical os. This marks the entrance to the uterus. The fallopian tubes are on either side of the uterus and comprise 3 regions. The portion of the fallopian tube closest to the uterus is called the isthmus, followed by the ampullary segment and the infundibulum. On the infundibulum's ends are finger-like projections called fimbriae that move like cilia and draw an ovulated ovum into the fallopian tubes. The junction between the uterus and the fallopian tube is termed the cornu.[2]

The ovary is suspended to the pelvic sidewall by the infundibulopelvic ligament (suspensory ligament of the ovary), containing the ovarian vessels.[2] The utero-ovarian ligament extends from the uterus to the ovaries and carries a blood supply from the uterine artery.[3]

Indications

Indications for ultrasonographic evaluation of the female pelvis include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Evaluation of pregnancy

- Fetal evaluation

- Intrauterine

- Ectopic

- Abortive process

- Infertility

- Evaluation of cause

- Evaluation of treatment

- Abnormal uterine bleeding

- Amenorrhea

- Dysmenorrhea

- Menorrhagia

- Metrorrhagia

- Incontinence

- Presence of pelvic mass

- Presence of infection

- Evaluation of anomalous anatomy

- Aid in performing an interventional procedure [4]

Other non-gynecologic entities may be evaluated as well as listed below:

- Bladder:

- Neoplasms

- Calculi

- Fistulas

- Cystitis

- Urethra:

- Small bowel

- Rectosigmoid colon

- Pelvic vasculature

- Adhesions [5]

Contraindications

Contraindications to the transvaginal ultrasound are the following:

- Rupture of membranes in a pregnant patient, as they are at an increased risk of chorioamnionitis

- Imperforated hymen

- Vaginal obstruction

- Recent vaginal surgery

- Lack of patient's consent [4]

Contraindications in pregnant women are premature rupture of membranes and bleeding from placenta previa.

Equipment

The equipment used during the transvaginal ultrasound include:

- Ultrasound machine with a transvaginal ultrasound probe

- Ultrasound gel

- Probe cover

- Table specialized for patient placement in the lithotomy position with stirrups, or the patient may lie on a flat table with a rolled towel or pillow under her pelvis to allow for probe maneuverability [4]

Personnel

An ultrasound technician conducts a transabdominal ultrasound and then follows with a transvaginal sonographic exam. Images are uploaded to a PACS system and made available to the radiologist for review and interpretation. The image quality and thoroughness of evaluation largely depend on the technician's proficiency and perspective to identify pathology and relay the images in a way that sufficiently allows the radiologist to interpret the ultrasound. A chaperone may be offered to the patient as this decreases misinterpretation or miscommunication during the exam.[6]

Preparation

The patient is asked to undress from the waist down and cover themselves with a gown. Lying supine, transabdominal ultrasound is first performed. A full bladder is recommended as this displaces the adjacent bowel loops that would otherwise distort the image and create an acoustic window, illuminating the organs behind it. Once completed, the patient is asked to empty their bladder. A disinfected transvaginal ultrasound probe is prepared by placing lubricant gel within the tip of the probe cover and then inserting the probe into it. Careful attention should be paid to eliminate any bubbles that may interfere with imaging quality as an artifact.

Technique or Treatment

The transvaginal transducer is inserted, with special attention paid to the image's orientation. A marker on the screen may indicate cephalad from caudad on sagittal imaging or right from left on transverse imaging, though various protocols are institution-specific.

The probe is placed in the distal vagina or against the external cervical os. Changing the depth of the ultrasound probe creates a different focal point and thus brings different areas within view.[4] Sagittal imaging is obtained with side-to-side movements of the probe from 1 adnexa to the other. Turning the probe to 90° gives us a transverse/semi-coronal orientation.[4] The transverse on endovaginal imaging is more of a coronal plane, while the true transverse image is done transabdominally.[1] Subsequent imaging is performed by moving the probe anterior to posterior. A general survey is performed as an initial evaluation by sweeping the probe from the midline to the lateral margins at the bilateral adnexa. The probe is then rotated 90° and swept in the anterior-posterior direction.[7] The cervix, internal os, endocervical canal, and occasionally the external os are imaged in both sagittal (long-axis) and transverse (short-axis) orientations.

The cervix is normally 2.5 to 3 cm and may be measured if there is an indication for it, such as recurrent second-trimester miscarriages in the setting of an incompetent cervix.[1] Benign nabothian cysts may be seen here, which are small and anechoic. Concerning the uterus, size, orientation, contour irregularity, and myometrial pattern should be addressed. The length of the uterus is measured on sagittal orientation, from the fundus to the external cervical os if able to image. Transverse/semi-coronal images should also be obtained with anteroposterior and transverse diameters measured. Volume may be calculated from these values. An anteverted uterus, the most frequently seen presentation, rests its fundus forward on the bladder, best appreciated on sagittal imaging, with the fundus oriented towards the top of the image. A retroverted uterus displays a fundus that orients posteriorly towards the rectum. To see a retroverted uterus may not have any clinical significance. However, it may be associated with deep infiltrating endometriosis in the posterior cul-de-sac or abdominal adhesions, particularly if fixed in this position.[8] The myometrial pattern should be homogeneous, and the uterine contour should be smooth. Heterogeneous parenchyma is non-specific, though it may be attributable to adenomyosis or fibroids. Not all fibroids need to be measured, but the measured ones should be measured in at least 2 dimensions.[8] The location within the layers of the uterus (subserosal, mucosal, submucosal) and which area of the uterus (left wall, fundus, lower segment, etc.) should be reported.

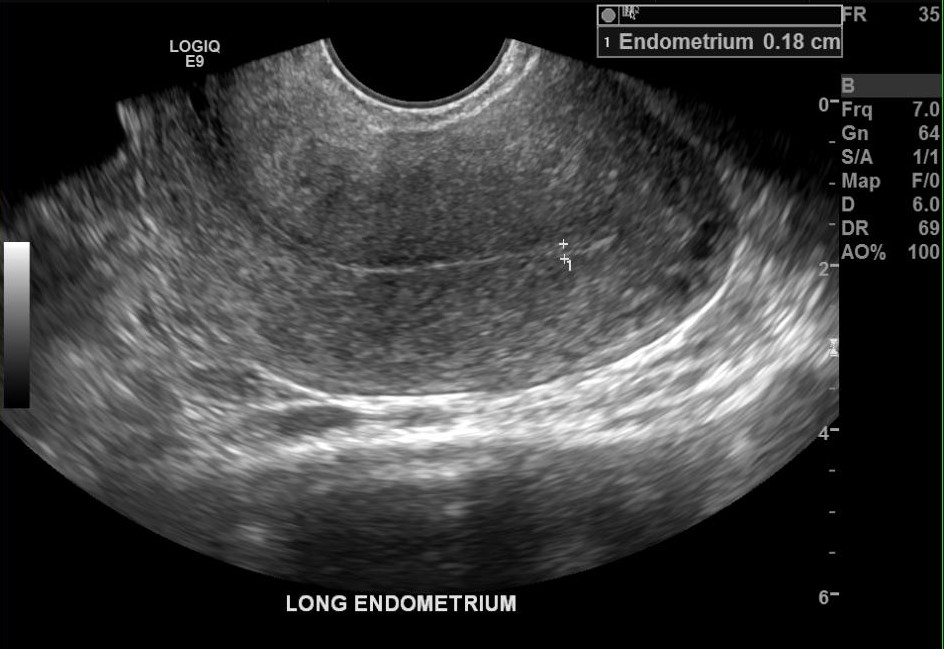

The endometrium, also called the endometrial stripe, is delineated by its normal echogenic nature, surrounded by the hypoechoic uterine myometrium. The thickest portion on true sagittal imaging should be measured. If the endometrial cavity has contents such as fluid or an intrauterine device, then it should be documented.[8] The sum of the thickness of the 2 parallel endometrial lines is recorded as the endometrial thickness in these cases.[9] Normal thickness varies for a premenopausal woman, which may be 3-5 mm during the proliferative phase of the cycle, with an upper limit of 6-12mm during the secretory phase. A maximum thickness of 5 mm is normal in a postmenopausal woman, even in women on hormonal replacement therapy or tamoxifen.[10] Endometrial irregularity, thickening, or cysts may be seen in the setting of adenomyosis. Endometrial thickness may also provide clinically useful information. Saline-infused sonohysterography is used to augment visualization of the endometrial lining and cavity and evaluate fallopian tube patency.[11]

Ultrasonography is the best way to identify the location of early pregnancy in the setting of an elevated beta-hCG; however, very early intrauterine pregnancy may be missed.[12] Furthermore, an ectopic pregnancy cannot be excluded. Hence, a follow-up transvaginal ultrasound and b-hCG are advised [13]. An ectopic pregnancy may occur almost anywhere along the female reproductive system; however, the majority (95%) implant within the fallopian tubes.[14]

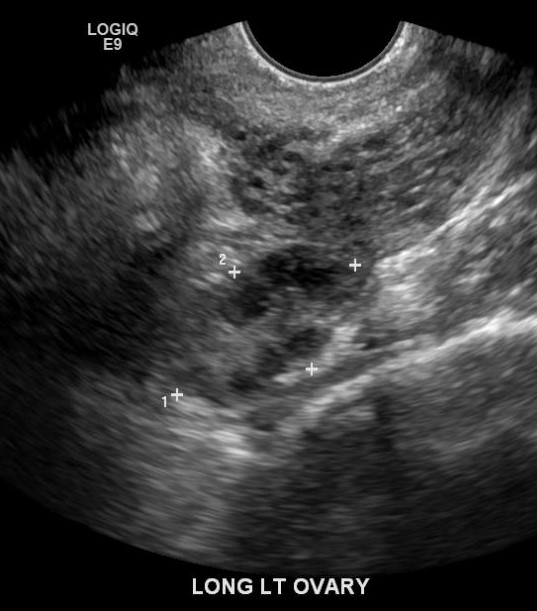

The bilateral ovaries should be measured in 3 dimensions by calculating the volumes. Any masses or prominent cysts should be measured as well. Physiologic follicles in a reproductive-aged woman may be seen (see Image. Sagittal Image of the Left Ovary). Masses, dilated tubular structures, and other abnormalities should be evaluated in the adnexal regions.[15] However, the fallopian tubes are not typically visualized if no pathology exists.[7]

A sonographer may perform dynamic imaging by placing a hand over the lower abdomen, palpating, and observing the mobility of the internal organs in real time. “Slide sign” is when the organs move relatively freely against 1 another. When they are more fixed during palpation, this is indicative of adhesions.[8] Additionally, regional sensitivity to probe maneuvers and anterior abdominal palpation may be pertinent to identifying pathology.[7] Another form of dynamic imaging may be performed by taking a cine-loop (video clip). When an area of interest is identified, a cine-clip allows the interpreting radiologist to characterize pathology more accurately than static images alone. Some protocols have cine-clip imaging as a part of their requirements.[16] The use of color Doppler has many utilities. It can assess the vascularity of an identified lesion, assess for hyperemic states such as infection, or assess for lack of flow, such as in the case of ovarian torsion. When a color Doppler is utilized, this must be mentioned in the reporting technique and findings. Once the examination is complete, the probe cover is removed, and running water and soap are used to remove any gel. After drying the probe, the utilization of a high-level disinfectant is recommended.[17]

Complications

Typically, there are no major complications with this procedure. The patient may experience some discomfort but should not feel any pain.

Clinical Significance

Ultrasound is a widely available tool, relatively inexpensive and timely, making it invaluable in evaluating emergencies. One of these medical emergencies is ovarian torsion, in which there is twisting about the vascular pedicle of the infundibulopelvic ligament and utero-ovarian ligament.[15] Venous waveforms are expected to initially become absent because vein walls are thinner and more compressible than their arterial counterparts.[15]

The contralateral normal ovary should be compared because of variability in blood flow appearance secondary to setting adjustment.[15] The ovary appears enlarged, and edematous and pelvic-free fluid may be seen.[15] A hallmark characteristic is the whirlpool sign, torsion at the infundibulopelvic ligament evaluated in cross-section.[18]

Seeing some or all of these findings on ultrasound strongly suggests ovarian torsion. However, there are a few caveats. Due to the dual blood supply from the ovarian artery running through the infundibulopelvic ligament and the uterine artery from the abdominal aorta, a patient without symptoms may demonstrate an apparent lack of blood flow to the ovary.[15]

Furthermore, the ovary may alternate between being torsed and reconfigured to its original position, which means that some of the above signs may not be present during the ultrasound.[15] Direct visualization is the mainstay for diagnosis. An appropriate diagnosis of ovarian torsion is made about 84% of the time.[19] The shortcomings of this modality should be known because ultrasound alone may not be sufficient to make a diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The proximity of the transvaginal ultrasound probe to the regions of interest allows for better image quality than its transabdominal counterpart.[4] It operates with a higher frequency transducer (5 to 7.5 MHz), resulting in less artifact. A higher frequency can only penetrate so much through tissue, making it ideal in the transvaginal route.[20] Additionally, there is marked difficulty in obtaining proper transabdominal sonographic images in an obese patient because of the amount of soft tissue the sound waves need to traverse; the transvaginal probe bypasses the pannus.[21]

The transabdominal counterpart operates at a lower frequency (around 3.5 MHz), allowing for deeper signal penetration (as is required) at the expense of poorer resolution. The transabdominal ultrasound also allows more flexibility to image a larger field of view, such as in the setting of the high-positioned adnexa because the probe may be moved anywhere across the abdomen.[22] Each modality has its strengths and shortcomings. Hence, combining the 2 methods provides a more accurate evaluation and earlier pathology detection.[23]